High Explosive Bomb at Bolina Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Bolina Road, Rotherhithe, London Borough of Southwark, SE16 2BB, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

In 1939, I was ten years old and lived with my family in a terrace house in Catlin Street, off Rotherhithe New Road, Bermondsey, South London.

I had two older brothers, John and Percy, two younger sisters, Iris and Beryl and a little brother Ron. My mother was expecting another baby in December who was to be my sister Sheila.

During the summer, war-scare was the main topic on the radio and in the newapapers, lots of preparations for Civil Defence were started.

Everyone was issued with a Gas-mask in a cardboard box with a shoulder string. Children under five got a "Mickey-mouse" model in pink rubber with a blue nose-piece and round eye-lenses.

There was a special one for infants, which completely enclosed the baby, and came with a hand-pump for Mum to operate.

It was a time of some excitement for us schoolchildren, clouded a little by fear of the unknown. All I knew about war was what mum and dad had told me about the Great War, when dad was a soldier and mum's family were bombed out in a Zeppelin raid when they lived at New Cross, Deptford.

Of course, things didn't happen all at once, you went to collect your gas-mask when it was your family's turn. Similarly, throughout the summer, gangs of workmen came round erecting Anderson shelters in the back gardens, street by street, a slow process. So the main topics of conversation at school were: "Got your gas-mask yet?" Or perhaps: "They've dug a big hole in our back-garden and are putting the shelter in today." This made one quite a celebrity, with looks of envy from others who were still shelter-less.

It was in the summer holidays when we got our shelter, so I didn't get a chance to gloat. Brother Percy remembers getting timber and plywood off-cuts from the local timber-yard to floor it out, but we were never to use this shelter in an air-raid as we moved to our new home in Galleywall Road before the Blitz started.

On the Wednesday of the week before War was declared in September, us school-children were told to pack our things and bring them with us to school next day as we were going to be evacuated from London. Although John and Percy went to different schools, they were allowed to come with Iris, Beryl and myself in order to keep the family together.

We duly turned up next morning with our little bits of luggage and had a label with our details on it tied to our coat lapels. Some of the kids were a bit quiet and weepy, but most were excited and chattering, speculating about where we were going.

Eventually, we walked in a long crocodile all the way to the back entrance of Bricklayers Arms goods station in Rolls Road. An engine-less train stood beside the wooden platform in the dim light of the goods-shed. We all got in and waited for what seemed an interminable time, then we were ushered out again and marched back to school. Our evacuation had been cancelled and we were sent home again. We never heard the reason why, but I think it must have been something to do with the railway being busy with military traffic.

On Friday the 1st of September, we assembled again at school early in the morning and walked in our procession to South Bermondsey Station, just a short distance away, each wearing a label, gas-mask case on shoulder and carrying a case or bag.

This time it was for real, and there was a special electric train waiting at the station, with plenty of room for all of us, but to the consternation of the big crowd of Mums and Dads who came to see us off, no-one could tell them where we were going, so it was a mystery ride.

The old type train carriages had seperate compartments and no corridor, so there were no toilets. I don't remember there being any problems in my compartment, although I was bursting by the time we arrived at our destination, but I expect there were some red faces in the rest of the train, especially among the younger children.

The journey took for ages, as we were shunted about quite a bit, and by mid-day we were getting hungry.

At last the journey ended and we found ourselves at Worthing, a seaside resort on the Sussex coast

Tired and hungry, we were herded into a hall near the station and seperated into groups, family members together.

Some of us were given a white carrier-bag containing rations, which I believe was meant to be given to the people we were billeted on to tide us over, but following the example of my friends, I dived into mine to see if there were any eatables. All the bag contained was a tin of condensed milk, a tin of corned-beef, a packet of very hard unsweetened plain chocolate that tasted like laxative, and two packets of hard-tack biscuits, which were tasteless and impossible to eat while dry. I think they must have been iron-rations left over from the first World-War.

A Billeting Officer took charge of each group and took us round the streets, knocking at doors until we were all found a billet This was a compulsory process, and some of the Householders didn't take too kindly to having children from London thrust upon them, so there were good Billets and not so good ones.

Some would only take boys or girls, but not both if they only had one spare room, so families were split up.

It was all a big adventure for me, and I wanted to stay with my schoolmate, Terry. We had teamed up on a school holiday earlier in the summer, and were good friends.

My two brothers were put into the same billet, and my sisters together in the house next door. They were all well looked after, but Terry and I were the luckiest

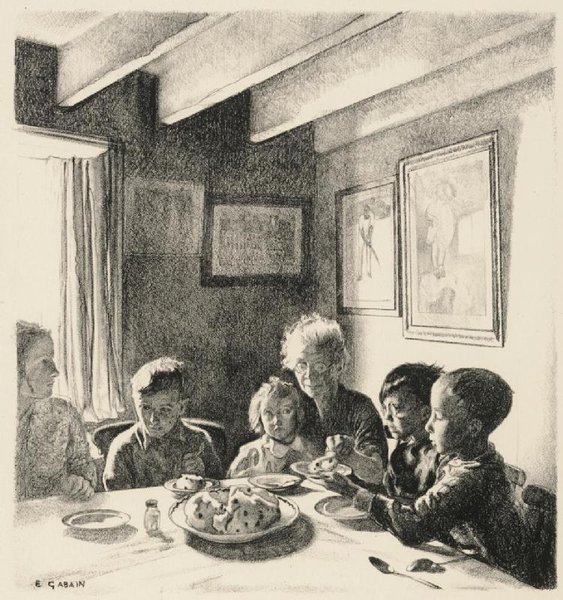

We went to stay with Mr and Mrs L at their house in Ashdown Road, Worthing. They had a teenage son and daughter, and Granny L lived in her own room upstairs.

Auntie Mabel, as we came to know Mrs L, was a lovely person. She treated us as if we were her own, and her Husband and the rest of the family were all good to us.

Auntie Mabel was always cooking and baking, and made sure that we ate plenty. Her Husband, who I will call Uncle L as I forget his first name, was a Builder and Decorator with a sizeable business and had men working for him.

He'd spent most of his life in the Royal Navy, and served on the famous Battleship, HMS Barham, during the first World War when it was in the Battle of Jutland. He had many tales to tell of his sea-faring life, and lots of photographs which enthralled me and made me want to be a sailor when I grew up.

His son, I think his name was Dennis, had only recently left school and started work. He became our special friend, and took us on regular outings to the Cinema, sporting events and the like.

His sister was a couple of years older. I don't remember much about her, except that her name was Edna. She was very pretty and worked at the local Dairy.

Granny L was very old. I believe she must have been in her eighties at the time. She used to wear long dresses, and wore her grey hair in a huge bun on top of her head.

She looked just like one of those ladies seen in old pictures of Victorian scenes.

She was very nice, and reminded me a little of my own Gran back in London.

We immediately hit it off together and became firm friends. She had lots of curios and pictures. Her husband had been a Captain on one of the old Sailing-Ships before the age of steam, and sailed all over the world.

He'd spent a lot of time in the South- Seas, and brought many souvenirs home. I remember some lovely Corals in a glass-case, and a couple of the largest eggs I'd ever seen. Granny L said they were Ostrich eggs, and came from Africa.

The L Family were Chapel-goers, and took us to the Service with them every Sunday evening.

It was quite an experience, being so informal after the strict Church Services we were used to at home.

Auntie Mabel looked rather grand in her Sunday clothes.

She used to wear her best coat and a big hat, which I thought was shaped like an American Stetson with trimmings. These hats were fashionable at the time, and it looked good on Auntie Mabel. She was a nice-looking lady, always smiling and joking.

It was a lovely summer that year, and the weather was fine and sunny when we went to Worthing, so we made the most of it and were on the beach on the morning of Sunday September 3.

We heard that Mr Chamberlain had announced on the radio at eleven o'clock that we were at war with Germany. Not long afterwards, we heard the wail of Air-raid Sirens, then the sound of aircraft engines, but it was one of ours and soon the All-clear sounded.

In the ensuing days and weeks, everything seemed to carry on as normal, the Seafront and beaches were open and without any defences, although this was all to change in the coming months.

The following weekend, it was still warm and sunny, and our little group were walking along the crowded Sea-front, when who should appear in front of us, but my Mother, and Auntie Alice, her younger sister.

They had both been evacuated from London as expectant mothers a few days before. Mum had heard rumours that our school had gone to Worthing, but our letters home hadn't arrived by the time she left, so she wasn't sure.

It was by a lucky chance that they'd come to the same place, and they knew we'd be at the Sea-front sometime if we were here, so they kept a constant look-out.

Mum and Auntie Alice were billeted quite a long way from us, so we only saw them at weekends, but it gave us a feeling of security to know that Mum was around.

However, she only stayed at Worthing for a couple of months or so until the first war-scare died down, although we had to stay on as there were no Schools open in London.

Our education carried on as normal at the local Junior School. One thing that stands out in my mind is that after we'd been there a while we were told by the Class-Mistress to write an essay on the most interesting thing we'd found while at Worthing.

At the weekend before, Dennis had taken us up on the South Downs behind the town to Chanctonbury Ring, a large circular clump of ancient trees on top of a hill.

There were prehistoric remains in the vicinity, and it was dark and eerie under the trees, the ring was reputed to be haunted.

There were quite a few tales going the rounds at school about it, especially the one about what happened to you if you ran round the ring three times, then lay down and closed your eyes.

You were supposed to experience all manner of weird things. On reflection, I think one would have needed to lie down after running round the ring three times. You'd have ran at least a couple of miles!

Needless to say, my essay was about our trip to this place, and I was all-agog to read it out in class when the Mistress randomly selected one of us to do so.

However, she chose Ronnie Bates, another friend of mine who lived just round the corner at home, and I can still see the look of horror on the Mistress's face as Ronnie proceeded to read out his lurid essay about the goings on at the local Slaughterhouse, which was on his way home from school, and seemed to fascinate him.

He often managed to get a peep inside, it was an old-fashioned place, and opened on to the street with just a small yard for the animals going in.

In the run up to Christmas, they formed a choir at school, and I was chosen to be a member. Then we were told that the BBC were organising a children's choral concert to be broadcast from a local theatre just before the Christmas Holidays.

Choirs from all the many London schools evacuated to Sussex taking part.

When the day came, we spent all the morning at the Theatre rehearsing with the BBC Orchestra, and Chorus-Master Leslie Woodgate. He was quite a famous man, well known on the radio, and really good at his job, so he got the best out of us.

Even I felt quite emotional when the concert ended with everyone singing "Jerusalem" acccompanied by the full Orchestra.

What seemed strange to me was the way Mr Woodgate mouthed the words at us as we sang, he looked quite comical conducting at the same time.

There was a sort of Lamp-standard with a naked red bulb on the front of the stage, and when it came on, we were on the air!

The Concert was interspersed with orchestral music and soloists as well as our singing. One item that I particularly recall was a piece by a lady Viola player, accompanied by the orchestra.

I had never heard of the Viola before, I just thought they were all Violins except for Cellos and Double-Basses.

The rich tone of the instrument impressed me very much, although at the time I was dying for the Lady to finish playing so that I could dash out to the toilet.

We were afterwards told that the Concert was a big success, but none of us were able to hear it on the radio. It was a live broadcast, as most radio programmes were in those days.

The weekend after school broke up for the holidays, Dad came down in a friend's car and took us home for Christmas.

I didn't know it when we left, but that was the last time I was to see Auntie Mabel and her family, as we didn't go back to Worthing after the holiday, but stayed at home in Bermondsey.

It was the time of the "phony war". Many evacuees returned to London, as a false sense of security prevailed.

Our parents allowed us to stay at home after much worrying. We heard that our School was re-opening after the holidays, and as I was due to sit for the Scholarship, I'd be able to take it in London.

This exam was the forerunner of today's eleven-plus, and passing it would get me a place at one of the private Grammar-Schools with fees paid by the London County Council.

To my great regret, in all the turmoil of events that followed with the start of the Blitz, and my second evacuation from London to join my new School, I didn't keep up contact with Auntie Mabel and her family. I hope they all survived the war and everything went well for them.

{to be continued}.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Home again in Bermondsey after the few months sojourn in Worthing, I saw my new baby sister Sheila for the first time. She'd been born on December 5, and Mum was by then just about allowed to get up.

In those days, Mothers were confined to bed for a couple of weeks after having a baby, and the Midwife would come in every day. In our case, the Midwife was an old friend of my mother.

Her name was Nurse Barnes. She lived locally, and was a familiar figure on her rounds, riding a bicycle with a case on the carrier. She wore a brown uniform with a little round hat, and had attended Mum at all of our births, so Mum must have been one of her best customers.

That Christmas passed happily for us. There were no shortages of anything and no rationing yet.

When we found that our school was re-opening after the holidays, Mum and Dad let us stay at home for good after a bit of persuasion.

I was a bit sad at not seeing Auntie Mabel again, but there's no place like home, and it was getting to be quite an exciting time in London, what with ARP Posts and one-man shelters for the Policemen appearing in the streets. These were cone shaped metal cylinders with a door and had a ring on the top so they could easily be put in position with a crane. They were later replaced with the familiar blue Police-Boxes that are still seen in some places today.

The ends of Railway Arches were bricked over so they could be used as Air-raid Shelters, and large brick Air-raid Shelters with concrete roofs were erected in side streets.

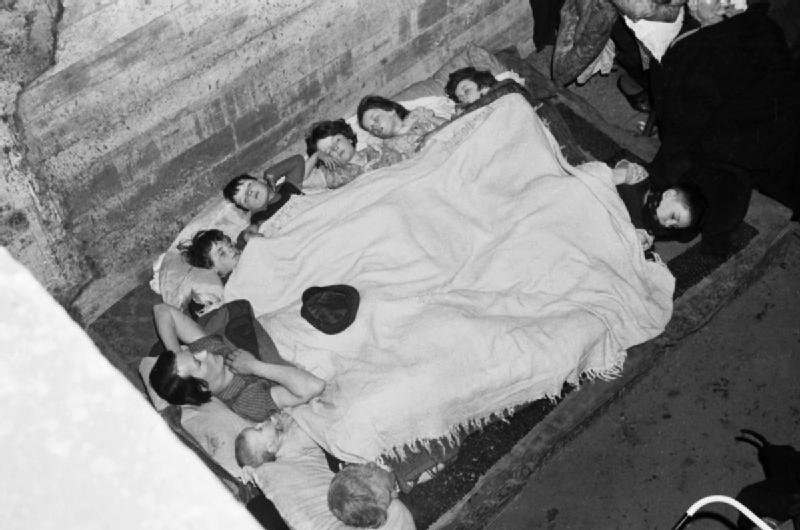

When the bombing started, people with no shelter of their own at home would sleep in these Public Air-raid Shelters every night. Bunks were fitted, and each family claimed their own space.

There was a complete blackout, with no street lamps at night Men painted white lines everywhere, round trees, lamp-posts, kerbstones, and everything that the unwary pedestrian was likely to bump into in the dark.

It got dark early in that first winter of the war, and I always took my torch and hurried if sent on an errand, it was a bit scary in the blackout. I don't know how drivers found their way about, every vehicle had masked headlamps that only showed a small amount of light through, even horses and carts had their oil-lamps masked.

ARP Wardens went about in their Tin-hats and dark blue battledress uniforms, checking for chinks in the Blackout Curtains. They had a lovely time trying out their whistles and wooden gas warning rattles when they held an exercise, which was really deadly serious of course.

The wartime spirit of the Londoner was starting to manifest itself, and people became more friendly and helpful.It was quite an exciting time for us children, we seemed to have more things to do.

With the advent of radio and Stars like Gracie Fields, and Flanagan and Allen singing them, popular songs became all the rage.

Our Headmaster Mr White, assembled the whole school in the Hall on Friday afternoons for a singsong.

He had a screen erected on the stage, and the words were displayed on it from slides.

Miss Gow, my Class-Mistress, played the piano, while we sang such songs as "Run Rabbit Run!" "Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree," "We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line," and many others.

Of course, we had our own words to some of the songs, and that added to the fun. "The spreading Chestnut Tree" was a song with many verses, and one did actions to the words.

Most of the boys hid their faces as "All her kisses were so sweet" was sung. I used to keep my options open, depending on which girl was sitting near me. Some of the girls in my class were very kiss-able indeed.

One of the improvised verses of this song went as follows:

"Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree,

Mr Chamberlain said to me

If you want to get your Tin-Hat free,

Join the blinking A.R.P!"

We moved to our new home, a Shop with living accomodation up near the main local shopping area in January 1940.

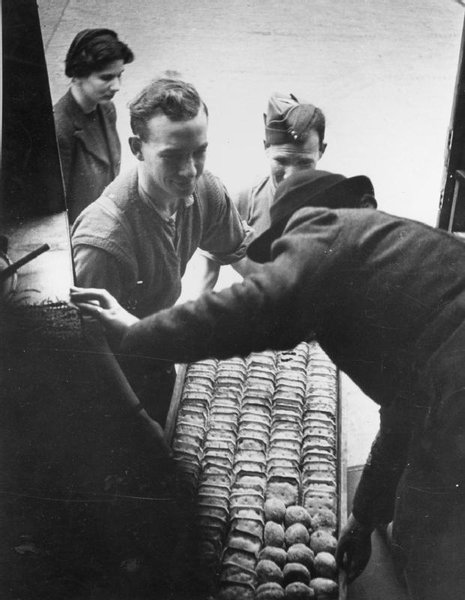

Up to then, my Dad ran his Egg and Dairy Produce Rounds quite successfully from home, but now, with food rationing in the offing, he needed Shop Premises as the customers would have to come to him.

His rounds had covered the district, from New Cross in one direction to the Bricklayers Arms in the Old Kent Road at Southwark in the other, and it was quite surprising that some of his old Customers from far and wide registered with him, and remained loyal throughout the war, coming all the way to the Shop every week for their Rations.

Dad's Shop was in Galleywall Road, which joined Southwark Park Road at the part which was the main shopping area, lined with Shops and Stalls in the road, and known as the "Blue," after a Pub called the "Blue Anchor" on the corner of Blue Anchor Lane.

It was closer to the River Thames and Surrey Docks than Catlin Street.

The School was only a few yards from the Shop, and behind it was a huge brick building without windows.

In big white-tiled letters on the wall was the name of the firm and the words: "Bermondsey Cold Store," but this was soon covered over with black paint.

This place was a Food-Store. Luckily it was never hit by german bombs all through the war, and only ever suffered minor damage from shrapnel and a dud AA shell.

Soon after we moved in to the Shop, an Anderson Shelter was installed in the back-garden, and this was to become very important to us.

As 1940 progressed, we heard about Dunkirk and all the little Ships that had gone across the Channel to help with the evacuation, among them many of the Pleasure Boats from the Thames, led by Paddle-Steamers such as the Golden Eagle and Royal Eagle, which I believe was sunk.

These Ships used to take hundreds of day-trippers from Tower Pier to Southend and the Kent seaside resorts daily in Peace-time. I had often seen them go by on Saturday mornings when we were at Cherry-Garden Pier, just downstream from Tower Bridge. My friends and I would sometimes play down there on the little sandy beach left on the foreshore when the tide went out.

With the good news of our troops successful return from Dunkirk came the bad news that more and more of our Merchant Ships were being sunk by U-Boats, and essential goods were getting in short supply. So we were issued with Ration-Books, and food rationing started.

This didn't affect our family so much, as there were then nine of us, and big families managed quite well. It must have been hard for people living on their own though. I felt especially sorry for some of the little old ladies who lived near us, two ounces of tea and four ounces of sugar don't go very far when you're on your own.

I'm not sure when it was, but everyone was given a National Identity Number and issued with an Identity Card which had to be produced on demand to a Policeman.

When the National Health Service started after the war, my I.D. Number became my National Health Number, it was on my medical card until a few years ago when everything was computerised, and I still remember it, as I expect most people of my generation can.

Somewhere about the middle of the year, I was sent to Southwark Park School to sit for the Junior County Scholarship.

I wasn't to get the result for quite a long while however, and I was getting used to life in London in Wartime, also getting used to living in the Shop, helping Dad, and learning how to serve Customers.

We could usually tell when there was going to be an Air-Raid warning, as there were Barrage Balloons sited all over London, and they would go up well before the sirens sounded, I suppose they got word when the enemy was approaching.

Silvery-grey in colour, the Balloons were a majestic sight in the sky with their trailing cables, and engendered a feeling of reassurance in us for the protection they gave from Dive-Bombers.

The nearest one to us was sited in the enclosed front gardens of some Almshouses in Asylum Road, just off Old Kent Road.

This Balloon-Site was operated by WAAF girls. They had a covered lorry with a winch on the back, and the Balloon was moored to it.

I went round there a couple of times to have a look through the railings, and was once lucky enough to see the Girls release the moorings, and the Balloon go up very quickly with a roar from the lorry engine, as the winch was unwound.

In Southwark Park, which lay between our Home and Surrey-Docks, there was a big circular field known as the Oval after it's famous name-sake, as cricket was played there in the summer.

It was now filled with Anti-Aircraft Guns which made a deafening sound when they were all firing, and the exploding shells rained shrapnel all around, making a tinkling sound as it hit the rooftops.

The stage was being set for the Battle of Britain and the Blitz on London, although us poor innocents didn't have much of a clue as to what we were in for.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by brssouthglosproject (BBC WW2 People's War)

The siren sounded 'All Clear'. The wail of a siren, for those of us who heard it in wartime, was never to be forgotten. We had come up from the underground shelter. Mum, Maisie, Stella, Evelyn, Betty and me. We stood there a little dazed but thankful, the bombing had ceased, at least for now. It had been a routine we had followed many times already. First the siren warning of an impending attack, then hurrying to the nearest shelter. As the time wore on trips to the shelter were more orderly with less rush and tear. We simply had gotten more used to it, finding also, that there was generally more time between the air raid warning and bombs falling. Indeed sometimes there were no bombs and the 'all clear' sounded almost as soon as you were underground. Other times we would stay in the shelter for hours. There was never much room so people were encouraged to keep their belongings to a minimum.

It was incredible what some folk would try to take down the shelter with them. The ever, vigilant Air Raid Precaution wardens would be heard 'you can't take that now, can you luv' as some poor old dear tried to take a cage down with her budgie in it. The shelters were damp and dingy. Cold at first, they would become hot and clammy with the amount of bodies in them. The aroma far from exotic would defy separation by one's senses, a melting pot of every odour the body can emit, and sprinkled with Evening in Paris (my dad called it Midnight in Wapping) lashings of slap and peroxide as some of the ladies were wont to use. 'Well I wouldn't go down the shelter without me face on, now would I!' Us kids took little notice of the all too familiar routine. The adults did the worrying, some more than others. Our mum Elizabeth, Liz to everyone, was an exceedingly tough lady. Although under five feet tall she could square up to most with a look followed by a flying shopping bag if need be. She would make sure that we were as comfortable as possible, but she wouldn't put up with any moaning either. She was an advocate of instant retribution: a swift smack around the ear was her preferred deterrent! If by chance she had meted out the discipline to the wrong child she justified her actions by saying: 'Well, you must have done something wrong that I don't know of, so it will serve for that'. Arguing with mum was futile.

We stood in a group on a small patch of green opposite the entrance to the shelter, the five of us, and mum. The sky was black with smoke and there were fires everywhere. This time we had not been so lucky. Our street had copped it; so had Elsa Street where we were all born, it was in ruins. For the first time in her 37 years of life, our lovely mum didn't know what to do. Like the amazing woman she was, after few minutes, composed, she turned to Stella and Maisie, the two eldest, and told them to look after Eve and me. She scooped Betty up in her arms and say to us 'Wait there I will find out what's happening'. Each direction she tried to take ended with her return after a few minutes. She would say 'Don't worry kids I won't be long' and off she would go again. The whole area had been flattened. Fire hoses wriggled along the ground like snakes, as they were pulled from building to building. Fractured water mains spurted fountains of water high in the air. Emergency supplies had to be pumped from the Regent's canal. Firemen, ambulance crews, civil defence members, and the heavy rescue teams were going about their work. The smoke stung your eyes, the dust got in your mouth and the acrid smell of gas lingered in your nostrils. Civilians, those uninjured and able to help others did so.

As if a vision, dad appeared. He seemed to come from nowhere out of the smoke and dust. With a look of panic on his face he asked 'Where is your mother?' 'Its all right' said Stella. 'She has gone to find somewhere for us to go and taken Betty with her.' His relief was instant. He asked if we were all right, then touched each one of us on the head just to make sure. His face was black, his blue overalls covered in grime, under his arm he held a helmet with the letter R for rescue painted on the front. For that is what he did throughout the Blitz. Defiant, he would never go down a shelter. Mum came back with Betty in her arms. 'Liz I thought something had happened to you.' With tears in his eyes he continued 'My London's on fire. I never thought I would see this day.' Like most East-Enders, dad thought London exclusively his. He would have died for her.

We gathered up the few things we had. Little did we know at that moment, it was all we had left in the world. Then we found our way to a reception centre. This one was a church hall, which was utilised as a shelter for those families who had been bombed out and now homeless, as indeed were many such places of worship. And very glad of them we were. The largest congregation most of them had seen in a long while!

About the middle of July 1940 the German Luftwaffe started attacking our airfields in an attempt to gain air supremacy, or at least to diminish our ability to attack their invasion force poised across the Channel waiting for the order to sail. So what did the cockneys do? They went hop-picking of course. They were not going to let Hitler ruin the only holiday most of them ever had each year. 'Goin' down 'oppin' was a ritual.

We mostly went to Paddock Wood. Whitbread and Guiness had big farms there. Each family would be allocated a hut. These were made of corrugated iron, but could, with a little flair, be made quite attractive.

When it rained conditions became challenging to say the least. There is a fair amount of clay in the sub-soil of Kent, a yellowy, slimy, sticky substance. When wet it sticks to everything and builds up on the heels of your boots so that everyone is walking around on high heels. I hated this and was continually teased 'Look Jimmy's wearing high heels'.

None of us missed out spiritually during our time in the hop fields. Father Raven saw to that. An East End priest, he spent more than 40 years in the service of his parishioners, even travelling with them to Kent each year where he had his own hut, and picked from the bine.

There had been enemy aircraft in the vicinity already and bombs had fallen in the neighbouring countryside.

Dad, mum,Stella, and Maisie were picking. Evelyn and I were playing nearby, Betty was in her pram close to mum. It was mid-morning, we could hear a drone from overhead getting steadily louder. Then, there were hundreds and hundreds of black shapes, like the migration of a million blackbirds. They covered the sky, blotting out the blue. The blood drained from my dad's face. Mum said quietly, 'My god Jim, is this it?' Apart from the pulsating drone of aircraft, not a sound came from any of the hundreds of pickers in the fields. We stood, numb, looking skywards. It was Stella's distinctive voice, 'Look, look everyone, silver dots, what are they?' She had been looking into the sun, something mum forbade us to do for fear of damaging our eyes. 'Spitfires, that's what they are, Spitfire's!' shouted dad. They came out of nowhere and pounced on the enemy bombers. All hell was let loose. People scattered in every direction, bins went over and hops were trampled in the earth. Dad grabbed Betty in one arm and me in the other, 'Run kids' he shouted, and off we went to one of the many trenches that had been dug in the event of an air raid. We reached the trench in no time; Dad hurled us into it. We fell on top of each other. For good measure dad grabbed hold of an old iron bedspring that happened to be close by, and threw it over us. An enemy bomb never hit us, but the bedspring nearly brained the lot of us!

From the cover of huts and trenches, people looked skywards and witnessed what was to become known as the Battle of Britain - now commemorated each year on 15 September as being considered the decisive day of the battle. It was the most amazing sight. Planes were shot down, pilots bailed out. Enemy planes that had been hit turned for home and dropped their bomb load at random. There was devastation in the hop gardens, bomb craters appeared everywhere; amazingly very few people were badly injured. We were on the way back to see what had happened to our hut when a bomb fell nearby, and the blast threw Evelyn up against the corrugated iron cookhouse. Unconscious, she had lost one shoe and all the buttons off her dress. Dad picked her up, and much to the great relief of everyone she eventually re-gained consciousness. Apart from some bruising, she was all right. However, we were all badly shaken. Dad and mum held council with a few close friends and made the decision to return to London.

The bombing of London had began on 7 September. One of the first buildings to be hit was the Coliseum Picture Theatre, in the Mile End Road, where dad and his partner Alex had performed so many times. Being in close proximity to the docks the East End was having more than its fair share. There was bomb damage all over. We took up residence and joined those making the nightly trek to the shelters. There was a permanent pall of smoke over the city, and a red glow, so that it never looked completely dark. Whilst spirited, ever-resilient and resourceful, the Cockneys were taking a pounding; and it was showing on the faces of many. Especially the mothers of children still in London. Evacuation was not compulsory once the intensified bombing had abated, the evacuees gradually drifted back.

At the reception centre, mum was having one of her migraines. When they fell upon her they were savage. She was lying down with brown paper soaked in vinegar wrapped around her forehead. It was the only way she found to ease the pain. We had seen her like this many times before and instinctively remained quiet. Stella sat close to mum comforting her and offering to get her whatever she asked for. Commotion and confusion ruled. The comings and goings of people looking for lost loved ones, the crying, and arguments, too many demands being made on the too few voluntary helpers. After a couple of days we were told we could be evacuated once more, We didn't know where, and we didn't much care.

The train was crowded as we headed towards the West Country. The five of us and mum sat on one side of the carriage opposite another family of evacuees. Evacuees. This label would stick for years to come and would be uttered in many tones with as many meanings. A parent could stay with a child if under five. Betty was two and I three and a half. Thankfully, mum was to stay with us for the duration, It was about four hours before we got to Bristol where many of the children were to change trains for various destinations. The train pulled into Yatton station. 'Come on kids this is where we get off,' said mum. The WVS ladies in green were there, trying to organise some sense of order.

After mum's protestations that in no way were we going to be split up, she finally accepted a place offered where we could stay together as a family. Mrs Kingcott, a well-dressed lady with a warm manner, introduced herself. She told mum she would take us to a farmworkers cottage, which was standing empty and belonged to Mr Griffin. Us kids were bundled into her little Austin Seven car. We were glad to be off that draughty platform. The blackout was in force so there was very little light. We peered threough the windows trying to make out the surroundings. Up and over a bridge we entered a tiny village. Mrs Kingcott explained: 'This is Kingston Seymour'. The car stopped and out we all got, and were escorted to the front door of a small detached cottage known as Rose Cottage. Little did we know that we would remain here for the next four years.

This story is taken from extracts from Jim Ruston's book, by his request and full knowledge and kind permission, His book: A Cockney Kid In Green Wellies, published by JR Marketing, 2001 ISBN 0-9540430-0-6,

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

CHAPTER FOUR

NEW CROSS

Despite my months of experience I felt like a new girl at school reporting at New Cross. To begin with it was the second biggest tram depot in London - only very slightly smaller than Holloway in north London - and there were no trolleys but far more tram routes: 36, 38, 40, 46, 52, 54, 68, 70, 72 and 74 and several of these routes shed the plough and went on the overhead wires outside the central area and I hadn’t needed to do any pole swinging at all at Wandsworth. The duties started and finished at different times too - the first sign-on at New Cross was 03.19 and the last tram before the night service took over reached the depot about half an hour after midnight.

Although everyone was friendly and helpful the depot was so big that there were more crews on the spare list than on the entire rota at Wandsworth and the depot was older and seemed so vast I got lost several times in the first few days. There were all those new routes to learn, new fare tables with strange stage numbers to memorise and there was more bomb damage too, which meant that landmarks had been removed. Discovering where I was along the routes was so much more difficult. A study of any London Transport fare table will show that the stages are named after well known buildings - mainly public houses and churches, thus acknowledging God and Mammon in more or less equal proportions - and when these buildings were reduced to rubble by bombing I found myself having to ask the passengers where we were even in broad daylight.

Even when new fare tables were printed the same names were duly recorded in the firm belief that every one would be rebuilt. Of course, this did not always happen, a fact that was brought home to me in a very amusing way. While working on the 68 and 70 routes through Deptford High Street I looked in vain for a certain public house known as the White Swan, not only could I not find it but there was no bomb damaged area along the stretch of road where it ought to have been. So, when a passenger asked for the White Swan I kept an eye on him and watched where he alighted. Sure enough it was just where I thought it might be but no White Swan anywhere in sight. Next day I picked up several people at the stop and asked them to show me where the White Swan was, only to be told that it was burnt down at least ten years previously and a small block of flats had been built on the site! For all I know, there is still a White Swan fare stage somewhere in Deptford to this day! Of course, not all passengers referred to the stops by their official names and I noticed that women tended to ask for certain shops while men asked for the nearest pub!

In time, of course, I got to know them all and the names of most of the side streets adjacent to the shops too, but I admitted defeat to one dear old soul who, when approached for her fare, asked, “How much is it?” When I pointed out that I was unable to tell her until she told me where she was going, she promptly replied, “I’m going to the doctor’s, dear. My legs are something chronic.” I patiently listened to her tale of woe, covering several visits to her doctor, the clinic and finally Guys Hospital - and right through an operation, apparently for the removal of varicose veins “such as the surgeon said he’d never seen before in all his born days,” when she suddenly jumped up, thrust tu’pence into my waiting hand, and, soundly telling me off for keeping her talking and nearly making her miss her stop, she tripped off the tram and across the road on her “chronic” legs and away down the street at such a pace I could only assume the surgeon at Guys Hospital had performed a miracle. Occasionally through the years I’ve had several people ask, “How much?” or “Is it still tenpence?” and I think of that old lady every time.

Now that I was working locally and able to work out the duties, I used to tell Gran when I would be going past the house and she would sit at the upstairs window and give me a cheery wave as I went past - till one night a bomb dropped across the road and shattered all the windows for several yards in all directions. The glass was replaced by thick tarred paper boarding which solved our blackout problems for the rest of the war and meant living in artificial light except in the warm weather when we could open them for light and air. Luckily, though, that was the nearest we got to being bombed ourselves and did me one good turn. Of course, we had an Anderson Air Raid Shelter in the back garden but, as it was always two feet deep in water in anything but the height of summer, we all huddled under the stairs when the siren went and the raiders were overhead. The elderly lady who lived on the top floor was very deaf and I used to dash up and bang on her door till I woke her up, then down to tell Gran to hurry up. The family in the basement always used to come to the ground floor too, they were scared of being trapped should the rest of the house collapse. But my Gran was obstinate - she would insist on getting dressed, fully dressed, and when I remonstrated I always got the same reply, “If I’m going to meet my Maker it’s going to be properly dressed, with my stays on.” So I’d wait fuming outside her bedroom (she scorned all offers of help - did I think she was a child or something?) till she emerged, fully dressed, corsets and all. The bomb which demolished several houses across the road exploded within minutes of the alert siren and with no guns to herald its approach and from then on Gran decided her Maker would have to accept her in her night-dress and dressing gown like the rest of us.

Thousands of people spent years sleeping every night in the Underground stations but they had to go there, with bundles of bedding and flasks of tea, quite early in the evening to bag one of the metal bunks which lined every platform - late comers slept on the platform itself or on deck chairs which also had to be carried through the streets or heaved on to a bus or tram. Our nearest Underground was at the Elephant and Castle, about a mile away, and Gran wouldn’t go that far so it was under the stairs for us night after night while the shells went up and the bombs rained down till it seemed we had been spending our nights this way all our lives. We still managed to do our day’s work, spending hours queuing for meagre rations, making do with powdered milk (not too bad), powdered egg (ghastly stuff but we ate it when our one real egg and two ounces of meat a week had been eaten), saving our precious clothing coupons and buying clothing for warmth and durability rather than style and fashion. But we were all in the same boat, united against a common enemy and the kindness and generosity I received from complete strangers made it all worth while.

Of course, the air raids weren’t the only hazards we had to face while working on the trams, the weather could play some nasty tricks too - especially the fog. There was no Clean Air Act in those days and, with factories going full blast twenty four hours a day and people burning everything they could lay their hands on when coal became short, we used to get some awful fogs in London - real pea-soupers, they were. When the driver could no longer see the track in front of the tram he would slide open the door and walk through to the back platform to ask for assistance. Then we would light the flambeaux or torches provided by the Board for just such an emergency. These torches were stout pieces of wood, about three feet long, bound with rags that had been soaked in some flammable substance. The driver would light the rags with a match and the conductor would then walk in front of the tram (or bus) waving the torch to indicate that the track ahead was clear. The old tram would grind and creak along behind at a snail’s pace and the driver and conductor knew they were going to be several hours late finishing that day or night. At least we were free of the air raids in the heavy fogs and that was some small comfort but the cold got to your bones, and your eyes were red-rimmed, straining to see through a mixture of fog and the smoky fumes from the flambeau. It was an eerie sensation, feeling your way through the choking fog and hearing sixteen and a half tons of tram moving close behind.

I must have walked miles like this in the two winters I spent in New Cross and several times an incident would occur which would break the monotony. One night we were proceeding through Deptford, near Surrey Docks, not a very select neighbourhood at the best of times. I was a few paces in front of the tram and we had been gliding through the fog like this for about an hour, when suddenly I got a shout from the driver, “Come on back, mate - we’re stuck - dead line.” I turned to retrace my steps and saw - nothing! No tram, no pavement and no sign of people - just thick yellow smoke, the oily flame of the torch in my hand and silence so deep you could cut it with a knife. I feared I had wandered off the track and held the torch nearer the ground to check but no, the rails still gleamed faintly in the flickering flare. Then a rattling chain and the thump of the platform steps dropping reassured me and I knew the driver was descending from the platform and coming to join me. I breathed a deep sigh of relief and walked a couple of steps back, almost colliding with the driver, and now just able to see the faint outline of the tram looming over us - but all the lights were out. “Better light another flare and prop it up the back - we are more likely to be hit from behind than in front,” said my mate. So through the tram we went, torch aloft, and lit a second one which we wedged between tram and buffers, making sure it slanted away from the paintwork. Meanwhile, the driver told me that there was no juice and we would have to wait till the electricity supply came on again before we could continue. “The last time this happened to me was when some idiot driving a lorry mounted the pavement and crashed into a substation,” he said.

Damage to a roadside substation cuts the supply of power to only a small section of road and the usual procedure is to wait till the engineers come along to fix it and send us on our way. But at 10 p.m. and in the thickest fog for years, how long was that likely to be? A friendly shout and measured footsteps heralded the arrival of a policeman, his black mackintosh cape dripping with condensed fog but a wide smile under his helmet. He told us he had been warned to look out for us. The driver had guessed correctly - it was a bus that had crashed into the substation box and rendered our stretch of line dead. “Can’t stop, mate,” he said, “Got to keep the next tram from running too far - they’ve got through on the phone to your chaps so they will get here as soon as they can.” So with that much information we had to be content and returned to the tram.

It might be just slightly warmer inside, we thought, but if it was we hardly noticed. We carefully counted our cigarettes - only five between us to see us through what looked like being a long night but we lit up just the same. We talked about the war, the job and our families and stamped up and down the tram trying to bring the circulation back to frozen feet and numb fingers. Our last passenger got off several stops past and we were beginning to think we were the last people left on earth when a faint call sent us hurrying back to the platform. There stood a man I recognised as one of the regulars who used the tram to travel back and forth to his job in the docks. “The copper just told me you were stuck here,” he said, “I’ve brewed up a pot of tea and stirred the fire up - only live round the corner - come on round and have a warm up.” I felt I could have hugged him but we couldn’t both leave the tram. No vehicle may be left unattended, even in these dire circumstances, so, like a true hero, my driver insisted on me going first. “Don’t worry, love,” said our saviour, “You won’t be all alone with me. I’ve got the old woman up.” And so it was.

The entire family of mother, father and four children lived in one room under appalling conditions. The children curled up in both ends of a single bed and the parents in a camp bed in the opposite corner. What with a kitchen table and chairs, a dresser and wardrobe cupboard and lines of washing across the room there was hardly room to move but all I saw in that first glance was the glow of the fire piled with tarred wooden blocks with flames leaping up the chimney. “Bit of luck, that,” said my escort, “They’ve just finished mending the road outside. Those tar blocks burn a treat, don’t they?” I had to agree. I wouldn’t have cared if he were burning the wooden seats of the tram right then; I was so glad to sit there in the high backed wooden armchair and watch steam rising from my clothes. “Let me pour the girl a cup of tea, Bert,” said my hostess. “Do you fancy a bit of bread and dripping, ducks?” Would I? But what about the rest of the family? A glance around the room told its own story. There wasn’t much money to spare in this household. My four pounds a week wages was probably much more than the breadwinner was getting to keep his family of six and they were offering me what was probably part of their breakfast. But I had no real choice - it was quite obvious that an offer to pay would have deeply offended them and a refusal might have made them believe I thought myself too refined for such humble fare. So down went the doorstep of bread and dripping between sips of hot tea from a slightly chipped enamel mug and it was wonderful. I knew I would have to go soon - I couldn’t forget my driver, still out there in the fog while I was warm and fed, so I got the tea down as soon as I could, but it was hot and Bert and his miss's were chatting away, mostly about their children.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

They admitted they should have sent them away when most of their mates’ kids were evacuated but they just couldn’t bear to part with them. The schools were closed down and they weren’t getting any education but the three boys were expecting to work in the docks like their dad and you didn’t need much education for that - not the kind the schools provided, anyway. Neither of the parents could read or write very much and the family had been dockers for generations so who was I to suggest they might aspire to higher things. No one could have been kinder than those two and when someone offers all they have to a complete stranger that puts them in a class above any other, in my opinion. I asked Bert if he would see me back to the tram so I could allow my driver to return and he was glad to see the pair of us. Then Ada turned up, “Don’t like to think of you out here all alone, duck,” she said. She had muffled herself up against the cold and followed her husband out into the cold fog to keep me company while my driver had his tea and a warm by the fire.

In the next quarter of an hour I had heard all about the children and how they could pick up a few coppers helping out in the local shops, doing errands for the old people and tackling a morning paper round. It must have been a happy family for all their poverty and I managed to get her to accept a shilling each for the children “From their new Auntie Doris,” I said. Apparently counting oneself as a member of the family made it quite acceptable and I didn’t feel so guilty wolfing down the bread and dripping after that. We had a cigarette and chatted on till my driver came back. We thanked our new friends once more and watched them disappear into the fog. It was after 11.00 p.m. by then and we knew the repair gang hadn’t mended the substation for we were still in the dark. They finally arrived about twenty minutes later and ten minutes after that we were on our way.

I walked ahead for about twenty minutes longer, picking up one or two passengers as the pubs turned out. It takes more than a London pea-souper to keep some blokes from their favourite hobby, it would seem. My first contact with these few “rabbits” would be when I almost cannoned into them along the track. Of course, they heard the tram coming and simply walked into the road towards it, swinging on as it crawled past at a snail’s pace. After the first couple I ticked my ticket rack into my moneybag and issued tickets on the road to save myself the effort of climbing on the tram each time. A couple of chaps must have come straight off the pavement and on to the tram without passing me, still plodding away in front, and I found their few coppers fare on my locker top under the stairs. People were very honest in those days and the poorer people were the more honest they were, it seemed. I think it was a matter of pride more than anything else was. You had to prove you could manage without getting into debt or asking for charity. In fact, charity was a dirty word to most working people - much dirtier, in fact, than some four-letter words bandied about today.

Hire purchase was becoming available for some goods but most people, especially the older ones, considered it not quite respectable to possess goods before they were paid for. My Gran always held these views and would go without rather than buy things “on the never-never”. She made me save part of my pay every week till I had enough cash to refurnish my room and start a home of my own. When I had the magnificent sum of seventy pounds in the bank, she took me along to the dockside warehouse and for sixty nine pounds cash we chose all my furniture - bed, large wardrobe, man’s wardrobe and dressing table in walnut (veneer), dining table and four chairs in fumed oak, settee and two armchairs in imitation leather known as Rexene, a twelve foot by twelve foot carpet square and fender and fire-irons for the fireplace. They lasted for years and years, in fact, I still have the wardrobe and dressing table and I’ve been married thirty-six years now. Our sense of values has certainly changed in that time till now the use of credit is regarded as normal and fare dodging, especially by the younger generation, has become the subject of self-congratulation rather than shame. I wonder why?

Of course, children didn’t use Public Transport much in the War, those children still living in London only rode on buses and trams when they were taken out by their parents for a treat. When the authorities realised that thousands of children had either never been evacuated or had returned to London the schools began to open again but the children walked to and from school as they had always done. There were no special school journeys as there are now and bus crews weren’t bowled over by a screaming, fighting and even cursing horde of school children twice a day as they are now either. And the tricks those little darlings get up to in order to avoid paying their fare would certainly disgust their grandfathers who used to leave their fare on the tram because the conductor was walking in front with a torch!

By this time we had reached Greenwich and it was well after midnight, and the fog was clearing, thank goodness. Our last passenger swung off as I climbed wearily back onto the platform. There was quite a long line of trams gliding through to New Cross, some from Catford, Lewisham, Brockley and Woolwich and we all carried on in convoy to the Depot. Then, after queuing up to pay in we dispersed outside the Depot and went our different ways home to sleep through what was left of the night. Of course, the night trams were running but all well late so I started to walk down the Old Kent Road rather than wait at New Cross Gate till one arrived. I heard it coming as I approached Canal Bridge and rushed out in the road to swing aboard. The driver pulled up right outside 234, saving me walking round the corner, and I was straight up the steps and into the house like a rocket. Although the fog came up again several more nights, it never got quite bad enough to make me get out and walk and it was weeks later when I was working in fog again and I had another incident which always raises a laugh when I retell it (which is probably all too often).

Although the fog was pretty thick on the Embankment, the driver told me not to bother to walk in front. The fog always hung heaviest along the river and it would clear up once we left the water behind us. It was quite late at night and I knew I should have to leave the tram to pull the points over at the crossroad the other side of Westminster Bridge. At all main crossings a pointsman sat, pulling over the points so that each tram went off in its proper direction, but once the evening rush was over and the pointsman finished for the day, then all point pulling had to be done by the conductor. Each tram carried a points lever, four feet long and made of iron. It took a bit of lifting across to the pavement - there it was fitted into a slot and pulled across to send the tram around corner. The lever had to be held against the tension of a heavy spring while the tram passed over the turning points. Then the lever was released allowing the points to return the track to the straight ahead position and the conductor pulls the points-iron out of the slot and dashes round the track to re-board the waiting tram. I had repeated this manoeuvre at lots of crossroads without any mishap so what happened on this night was completely unexpected.

The driver pulled up at the usual spot and I alighted with the points bar and crossed to the pavement. The fog was rising from the river and swirling round my feet and it took me a little time to find the slot in the pavement and insert the iron bar. I strained to pull it across and felt the spring points engage. “Okay, mate - full ahead!” I yelled and the tram pulled away and I hung on to the bar. It was damp and threatened to slip from my grasp. I knew if I let go while the plough was slipping from one track to the other then the plough would buckle and the tram would be in a position with the front wheels on one track and the rear wheels on another. The mind boggles! I desperately hung on and breathed a sigh of relief when I heard the rear wheels crash against the points and continue round the corner. For some reason the points-bar seemed jammed and I tugged it first one way and then another till finally it jerked out of the slot, nearly throwing me off my feet. I looked to where I thought the tram should be waiting and saw nothing but fog so I started walking along the pavement, peering hopefully into the road, still looking for my tram - still nothing but fog. I began to hurry faster; surely I should have reached the crossroad by now?

Walking along the pavement and staring into the road I collided violently with a gentleman dressed in blue serge and found myself looking up into the bearded face of a tall policeman.

“Oh, good!” I exclaimed, “Have you seen a tram?”

“Hundreds,” was the unhelpful reply, albeit accompanied by a twinkle in his eye and a broad grin. “Now, what’s the trouble, young lady?”

“I think I’ve lost a tram,” I replied, plaintively and the grin melted into a chuckle and the chuckle into a roar of laughter. I began to see the funny side of it myself by then and we both laughed and I nearly choked trying to explain and stop laughing in one breath. Now, don’t ask me how I’d managed it, but I’d not only started walking in the wrong direction but even managed to cross the road without realising it and we were both standing just under Big Ben, a point emphasised when it boomed out the half hour chime right over my head.

So, held firmly by the elbow, I was marched across the road and over the bridge again to be met by a bewildered but very relieved driver who had broken the golden rule and left his vehicle unattended to look for his scatty conductor. The laughing policeman insisted on staying with us till I was safely back on my platform and when the passengers were told what had happened they rocked with laughter too. Was my face red! “Well I’m certainly glad we found you alright,” said my friend in blue, “I’ve never had to report a lost tram before.” We made up the time before we finished the duty so I didn’t have to fill in an official report - but the story soon got around and I wasn’t allowed to forget it for the rest of my stay at New Cross Depot.

The days of Winter eventually gave way to Spring and now it was lighter in the evenings and people went out more, the air raids slackened off for a while and the sale of sixpenny evening tickets went up by leaps and bounds, whole families would sally forth to visit relatives they hadn’t seen for months and many a romance blossomed on the top deck while we bowled along the country roads of Bromley, Grove Park or Abbey Wood. We were even busier all day Sundays and when the Easter Bank Holiday Monday arrived several extra trams had to be pressed into service to cope with the queues of passengers at almost every stop. Despite the long list of spare staff in the Depot, the call went out to all depots to ask for volunteers to do overtime and rest day working throughout the holiday weekend. People came out in their thousands to visit Greenwich Park where they spent the day picnicking on the grass or sitting round the bandstand listening to the brass band or walking through to Black Heath to the Fair.

It was, of course, traditional in those days to buy new clothes for Easter and very smart and happy they all looked too. Working people only had two changes of clothing then, one for best and the other clothes they wore to work. Every Easter out came the carefully saved up clothing coupons and a new best outfit chosen. Children’s clothes were usually purchased one or two sizes too large to allow for growing and mothers were busy just before Easter putting deep hems on dresses and trouser legs and taking in side seams with big stitches they could easily unpick the following year. Cotton wool would be stuffed into the toes of boots and shoes that were a couple of sizes too large and last years best brown shoes would be sent to the menders (or resoled and heeled at home) and dyed black to smarten them up for another year’s wear at work or school. When money and coupons ran out, linen hat-shapes would be purchased at the local draper’s and covered with pretty material costing about one and sixpence a yard, half a yard would be plenty for one hat, so two sisters or mother and daughter could have new hats at a cost of half a crown (twelve and a half pence) the pair.