High Explosive Bomb at Calvert Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Calvert Road, Charlton, London Borough of Greenwich, SE10, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by nationalservice (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was added to the site by Justine Warwick on behalf of Alan Tizzard. The author is fully aware of the terms and conditions of the site and has granted his permission ofr it to be included.

This is the story of how wartime stole my childhood and forced me to become a man

Saturday the 7th September1940 was a glorious summer day. I was 10-years-old, sitting in the garden of my parents home in Hither Green Lane just off Brownhill Road, caught up in the knock-on effect of the teacher shortage at Catford Central School in Brownhill Road and attended mornings one week and afternoons the next.

This was the case for those of us whose parents would not be parted from their children, or whose wisdom suggested something was fundamentally wrong with evacuation to destinations in Kent or Sussex. Surely these places were nearer the enemy across the Channel?

Anyway, I was at home with my mum, dad and older brothers and sisters and it was great!

My dad, because, he was a Lighterman and Waterman on the Thames and had been a policeman, found himself on the fireboats patrolling the river to

put out fires caused by enemy planes. My brother-in-law Jim was in the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) stationed in a nearby school. He drove a commandeered London taxicab that towed a fire pump trailer. Brother Ted was a peacetime Royal Marine, serving on HMS Birmingham. Brother Chris, at 16 years was crazy on American gangster films and used to make wooden models of tommy guns they used. He encouraged me to make model aircraft from the Frog Model kits of those days.

On that sunny Saturday afternoon in early September I was sitting on the kitchen step whittling away at my model when the sirens sounded. No sooner had the sirens stopped than the fírst planes came into sight. They were high, by the standards of the day, maybe twenty thousand feet. Hurricanes and ME109's. They were twisting and turning, weaving and bobbing. To me this was a grand show. So far my sight of war had been at a distance and knocked the cinema version into a cocked hat.

Suddenly what had been a spectator sport, not wholly real changed to War. I was to leave childhood behind forever.

From the front of the house we did not see the approach of that part of Luftflotte Zwei from across the Channel as they came from behind us. A sudden shower of spent machine cartridge cases rained down all around us. What had been the relatively dull ever-changing drone of the fighters in dog-fights high above our heads with their guns making no more than a phut, phut changed to pandemonium. The stakes had changed. We were now a part of it.

Chris said: "I think they're trying for the bridge." As he spoke, a Heinkel 111 flashed into sight coming in at an angle from our right. I believe it was being chased by a fighter as another shower of empty cases came down, bouncing and pinging on the front garden paths and pavements. Suddenly an aerial torpedo fell away from the Heinkel, which seemed to bounce higher into the air as the weight of the missile fell clear. The Heinkel disappeared, climbing away to its right out of our sight. Some seconds later we heard the explosion.

Two.

Later, in a conversation, my brother-in-law t the AFS man stated the showrooms had copped it from an aerial torpedo. From his comments and the first hand observation of my brother and myself that afternoon, I believe the Heinkel 111 we saw was the culprit.

I am not sure. But this much I know that was the day I stopped being a little

boy. I think it was seeing German planes still managing to fly in formation not withstanding all that the Hurricanes were doing to try to stop them, that took away my innocence.

Two days later, on the afternoon of Monday September 9,I answered a knock at the front door of my parents' home and was taken aback by the spectacle of a man so covered in oil and filth from head to foot that I didn't at first recognise my brother-in-law. Jim the firefighter had gone on his shift on the afternoon of 7th and had only then returned. Calming my alarm at his state, Jim explained that his unit had been in I he docks fighting fires

for over 72 hours and that at one point had been blown into the oil-covered waters.

The filth laden atmosphere pervaded the air for days. The sky to a great height wreathed with smoke of all colours that glowed red, orange and in some places blue.

Soot seemed to fall contínually and as you wiped it away it smeared your hanky and smelt of oil.

On the afternoon of the 11th September the sirens went again. We were all getting very weary from the raids, Í was little more than a young child and I had, had enough. I can't imagine what it must have been like for the grown up members of my family. ^^^H

Certainly, we had by now we had given up trying to brave it out when the bombing got local. So my mother, two sisters, my brothers Chris and Arthur and Jim, all climbed into the Anderson shelter in the garden.

Usually the doors were pretty firm. But things were really getting hot outside. All hell was going on out there

The door was hammering against the shelter and coming loose - at one point Jim leapt forward and simply held on while I was pushed to the floor and my sister Maisie threw herself on top of me As I lay pinned down I could see Jim rocking to and fro at each blast from outside.

I don't know when, but in due course things became quieter, and Jim climbed out. I don't recall actually leaving the Anderson, but I do

remember what 1 found outside. My mother's orderly wartime garden, her pride and joy, was a wreck. The back door to the house 'was laying in the yard. All the rear windows were gone, where the frames had survived shreds of what had been net curtains hung in tatters.

The whole house was in tatters. The road outside was a shambles, everywhere were those empty cartridge cases. Arthur and I started collecting them looking to see if they were theirs, or ours. Over on the other side of the road, a showroom was burning, soldiers were milling around some kind of control vehicle with a dome on top painted in a chequer-pattern. I believe they must have been bomb disposal chaps.

Three.

I remember later, in the back garden my brother Arthur endeavours to chop with a garden spade the burnt half of an otherwise un-burnt incendiary bomb that he had found in the front garden.

The whole thing had an unreal feeling about it. It was then that my family moved.

I have no recollection of any decision being taken by my elders to leave the house. I do recall being in the back of what must have been a 15-cwt Army lorry with some but not all of my family. The vehicle bumped away from our house and as I looked through the back I was being cuddled by my older sister Maisie. The sky was yellowy and smoky. Opposite and to the left of our house five houses had five houses had their upper floors torn away, our lovely Methodist Church and my cub scouts' hall had totally disappeared.

The 15-cwt turned left into Wellmeadow Road and made its way to the rest-centre at Torridon Road School where we remained until the 15th September before temporary evacuation to Sutton-in-Ashfield Notts. We returned to Bomb the Alley of southeast England after a short respite and I regarded myself as grown-up for the remainder of the war.

NB:This article written by me appeared in The Greenwich Mercury November 28th1996.

The article was accompanied by two photographs one of me in my parents wartime garden of the house from which we were bombed out shortly after it was taken.

The other photograph was taken in 1954 following my return to England having been in the Occupation Army in Germany.

The little girl in one of the pictures was Joyce Eva Maycock of Hampton Village, Evesham, Worcestershire a sweet little thing from the country not realising she would later marry the urchin above. (as I write this Tuesday, August 03, 2004 come tomorrow Wednesday 4th August 2004 we shall have been married fifty years)

Contributed originally by ReggieYates (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Canning Town Evacuee — Part 3

Starting Work

Having returned from being an evacuee, on my 14th birthday I started work for a firm called A. Bedwell & Sons who supplied grocery and provisions, delivering to grocery shops around London, Essex and some parts of Kent.

The firm no longer exists as the end of the war saw delivering to shops become outdated with big warehouses springing up who sold to shopkeepers willing to pay for goods as they wanted them in bulk.

I started as a van boy and when I was seventeen, I was officially allowed to drive a one ton van all by myself, and took another van boy on our delivery through Blackwall Tunnel, up the big hill to Blackheath and via Kidbrooke to Crystal Palace, then back via Lydenham and through Blackwall Tunnel again. Quite a nice day’s work, safe and sound. I really enjoyed myself and have never looked back.

We also had to pick up a load from various wharfs, another warehouse and some firms, at the same time looking out for any chance of getting things that were on ration. The war never ended until I was seventeen years old and rationing didn’t cease completely until about 1952, although as time passed things got easier and easier.

One of the vans I drove was an old model T type Ford with large back wheels and the body on top of the chassis, which made it heavy. It was hard to control in wet weather, the engine was so ‘clapped out’ it couldn’t climb a hill to save its life and it used half a gallon of oil every day which used to come out of the radiator cap with hot water, making an awful mess.

Going to one shop in Potters Bar we would fill the van right up to the maximum weight and at a big, long, steep hill we would try to get at least half way where there was a gate that allowed us to turn around and reverse the rest of the way up until just before the top where we turned around in a field and continued to the top facing the right way but smoking and steaming.

We kept complaining about the van and after about three months it would not start, so the garage mechanic said he would take it off the road and strip it down. The next day he called me in the garage to see the state of the engine. The van was eighteen years old so I expected the worst but was still amazed. The inside of the piston bore was red rust and oval instead of round and the valves were burnt so much that the round bit at the top of the valve was half the width they should be. He reckoned the engine had been running on fresh air for years.

He told the boss it would cost more to repair than to buy a new one, which was reluctantly agreed to and so he bought a smaller van which is similar to today’s transit.

The new van climbed the hill in Potters Bar first time, but on the way back I skidded it in the rain and finished side ways in a ditch which I managed to get towed out for a couple of quid. Luckily there was no damage apart from some paint scratches, which the mechanic sorted out for me for a drink. Nobody was any the wiser - I hope!

Another day I was driving a long wheelbase Bedford lorry in Leytonstone and the steering snapped, I hit the kerb and finished in someone’s front garden, lucky again! All this in my first year as a driver, mishap after mishap.

There was another time while I was driving to Romford in monsoon conditions at about ten in the morning, I got as far as The Dukes Head pub in Barking when I saw a trolley bus at a stop on the opposite side of the road and an army three ton lorry coming along behind it to overtake. The army lorry stopped beside the bus leaving me nowhere to go except between the army lorry and a lamp post which I did, but the top of the body and sides of my truck jammed between the lamp post and army lorry with the rest including me continuing down the road for twenty yards. To make matters worse all the goods were now exposed to the elements. It was like a scene from a Laurel and Hardy movie!

Fortunately for me a police car behind the army lorry stopped and the officer told the army driver to stay put, then guided me back under the van’s body. We borrowed some rope from a nearby garage and tied down the body to the floor. After ticking off the army driver for being so stupid he escorted me back to my firm near the Abbey Arms in Plaistow. Another one I got away with!

While I was a van boy and still only sixteen, (you couldn’t legally drive until seventeen) my driver decided to teach me how to drive the van. He put a blindfold on me and made me feel the gears, levers, clutch and gas. Then he revved the engine so I could hear the sound of the engine and feel the clutch ‘bite’, and drove so I would know by the sound of the engine when to change gear. Soon he taught me to drive the van for real on the quiet back roads and eventually let me on the open road.

Every Tuesday while he was courting, he would pick up his girlfriend from work and take her home where he went in for a bit of nookie. I had to wait in the van before we carried on with our deliveries. Her mother always used to make me apple pie and custard, which I ate in the van while waiting. Once he had taught me to drive, he let me take the van on my own (age sixteen) to continue deliveries while he had his nookie.

During Christmas 1945, my mate who was my driver got married to his girlfriend. She lived in Gidea Park, Romford and worked at Romford Steam Laundry (where Romford Police Station is now). The wedding was a big feast and drink up, which lasted right up to the New Year. His dad bought a forty gallon barrel of beer from the Slaters Arms and we pushed it home to his house, where we took his back fence down so we could get it in the garden and lift it on to a stand he had made so we could get the beer easier.

His dad said “nobody goes home until all the grub and beer has all gone”, so we stuffed ourselves silly with all the drivers eating 30lb of cheese, 4 x 7lb of spam, 10lb of butter, a big bag of spuds, many loaves of bread, 10lb of bacon, three dozen eggs, 4lb of tea, a case of evaporated milk and a big bar of Ships chocolate used for making drinks.

I got home on New Year’s Day at teatime stinking like a polecat with a week’s growth of hair on my face. I really enjoyed myself.

Starting back at work I found two new Morris Commercial three-ton lorries and I got one after we all tossed up coins to see who would get them. Lucky me, it was a lovely lorry to drive, pretty fast as well.

Coming back from Chatham the police would chase us every week for speeding, but could not catch us because we were having a cuppa in a wayside café when they caught up with us. Mind you the police in those days had 200cc motorbikes. It was not until later that they had much faster bikes like 500cc Nortons and Triumphs.

It was not long after this incident that I had to go to a South London wharf in Tooley Street to pick up five tons of sultanas. Coming up to Tower Bridge, the bridge was up, so I crept up on the outside of the queue of traffic. In those days there were still a lot of horse and carts around so it was a crawl over the bridge.

Just as I got over the bridge on the east side I saw an old motor coach come out of Royal Mint Street onto Tower Bridge. There was an obelisk there dividing the road for southbound traffic but you could go either side. I stopped dead so the coach could get by and a horse and cart came up on my near side. The coach kept coming and I could see that it was going to hit us if it didn’t pull over a bit, so I told my van boy to quickly get under the dashboard and curl up.

Unfortunately the coach did hit us, right in the radiator and the bonnet flew off into the River Thames. Our engine came back into the cab, the gearbox came up through the floor and five tons of sultanas went all over the cab. Both doors caved in trapping me in the cab right against the steering wheel and the offside front lamp of the coach came through the nearside windscreen, frightening my van boy because he could not move.

Somebody called the police, fire brigade and ambulance. Fortunately they managed to get my van boy out in minutes, but I was stuck for about forty minutes until they cut the steering wheel in half and forced the door out.

Imagine my surprise when I was pulled out, I never even had a scratch. My saviour was a leather belt I wore to keep my trousers up and an old army belt I used to wear around my boiler suit. The steering wheel went flat where it hit my belt and saved me from any injury.

When I got to hospital they could not believe that I didn’t even have a bruise. I was so lucky.

The coach driver had more room than me to get by and needless to say, he was charged for driving without due care and attention.

These are just a few of my memories of WW2. I hope you enjoy them. I am certainly enjoying reading all the stories from other people.

I now live in Devon.

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

I used to love working over the Easter Weekend even though it meant extra hours of overtime and no day off for two weeks or longer. Very few employers gave their workers a paid holiday every year but London Transport did. Of course, like everything else, it was done at each garage or depot on a rota basis and the less fortunate among us had to take our holiday outside the summer months. The holiday rota stretched from 1st March to 31st October and we all volunteered to do rest day working throughout that period to cover duties of those on holiday. Provided the services were kept running, the authorities were very lenient, especially if a husband arrived home on leave and the girl’s holiday was still months away. Either her holiday would be swapped with someone due to start the following week or a call would go out for volunteers so the week’s holiday would be covered, day by day, with rest day workers. The girls would invariably put a cross alongside their name on this list to signify that they would do the duty without pay and several of the men conductors would do so too, although the extra pay of time and a half for rest day working was a very great sacrifice for those among them with families to keep. Of course, we all knew that the same would be done for us if the occasion arose but, even so, it was really a great deal of comradeship that bound us all together. I only wish the same spirit prevailed today - regrettably it does not.

Unfortunately the lighter evenings encouraged people to go further afield for their evening drinks too. Instead of slipping round to their local and staggering home at closing time they would take a tram ride or travel a short distance from pup to pup along the road until they found themselves miles from home. Then I would have to memorise where each of them was going and shake them awake or stop them in mid-song when we reached their destination. Some were so drunk it is a wonder they ever made it and my heart would be in my mouth when I saw them half climb and half fall off the platform and lurch through the traffic. Of course, there wasn’t the mass of cars on the road as there is now, petrol was strictly rationed for business journeys and only the well to do could afford cars anyway. But, even so, alighting from a tram in the middle of the road in the blackout always involved some element of risk. To enable us to be more easily seen by other traffic we had a broad band of white shiny material (similar to plastic) above the wrist on the left arm of our jackets and overcoats which could be wiped clean with a damp cloth. The whiteness gradually turned to yellow as the months went by till we wore white again after our yearly renewal of uniform.

The crews would sit in the canteen on meal breaks and swap stories involving drunken passengers - some amusing, some pathetic and others not pleasant at all. I still remember a few of my own. One dark night, along the Old Kent Road we were hailed by a young sailor who, somewhat dismayed to find he was talking to a woman conductor, asked if I would mind him bringing his mate along. He explained that they both had to get to Woolwich and from there a train to Chatham where they were due to join their ship at 7.30 a.m. “I’m afraid my mate is a bit under the weather,” he said, “but we’ll be in dead trouble if we don’t catch that train. I’ll look after him, Miss; I promise he won’t be any trouble if you will take us to Woolwich.” Well, with my Bill in the Navy I always had a soft spot for sailors but “under the weather”! - his mate was so drunk he was almost in a coma, propped up against the wall of a pub, dead to the world. They both had fully packed four-foot long kit bags with them and a small suitcase each too. So we loaded the luggage on first and I took it under the stairs so they didn’t have to buy luggage tickets (no string!). My driver came round to find the reason for the delay and he must have felt sympathetic to the Fighting Forces too because he leant a hand, between us, we managed to carry the unconscious sailor into the lower deck where we laid him out on the long seat. Regaining consciousness for a few seconds he opened his eyes, said, “Goodnight, Mum,” and lapsed into oblivion again. I dissolved into a fit of giggles - he was about ten years older than me anyway - and his young mate broke into a torrent of apologies - he was only about nineteen years old himself and a teetotaller into the bargain and so scared they would both be turned off again if his mate upset anyone. Of course, we had lots of passengers between the Old Kent Road and Woolwich but everyone understood and sympathised with the two blokes on last night of their leave, going out to sea the next day to face the elements - to say nothing of the German U-boats. When we reached Woolwich half a dozen passengers got out of their seats to assist the sailors and luggage off the tram and safely on to the pavement. Two chaps volunteered to help with the source of all the action (now slumped at a foot of a lamppost with an angelic smile on his face). They had both taken tickets to Plumstead but assured me they could take a later tram or even walk home if necessary after seeing the two sailors safely on their train. I waved them good-bye with many thanks and hoped another lovely crowd would do the same for Bill should the occasion arise!

Another drunken sailor provided an episode which was not so amusing - to put it mildly. To begin with, he insisted on trying to go upstairs - a manoeuvre I judged to be unwise - if not impossible in his state. After several stumbles, lurches and not a few strong words he finally made it to the top deck with me in close attendance behind in case he should fall backwards. I sighed with relief when he collapsed on a seat and I returned to the platform. We were running late, having stopped for a while in an air raid and the driver was really pushing it along. So down the empty road we rattled, swaying and lurching as usual till we reached Woolwich Ferry where I had to swing the pole and fasten it down while we took up the plough. As I regained the platform I heard a shout from the window over the platform and I looked up - and the sailor was sick all over my face and head. Now the smell of vomit is nauseous enough under normal circumstances but when a man has been drinking both beer and spirits, and it is literally right under your nose - it is indescribable. It was in my eyes and hair and dripping down on to my shoulders and all down the front and sleeves of my tunic. I dashed round to my driver nearly crying and he tried to wipe away most of the foul stuff with an enormous red and white spotted handkerchief, but it was obvious I couldn’t face the passengers or continue my duty in that state. So he told me to climb up onto the driver’s platform while he went round to ask all passengers to alight and wait for the next tram. When we explained the reason the passengers went up and dragged the sailor off the tram, telling him just what they thought in no uncertain terms.

Then away we went, down the road, non-stop to Charlton works where all the trams were serviced. There was a hurried consultation with the Chief Engineer and I was escorted into the washroom. I was on entirely male territory here as no women were employed at Charlton, so the engineer and my driver posted a man on the door to keep everyone else out. Then they helped me off with my tunic and set to with a sponge to clean the worst off while I washed my hair. They went outside while I took off my blouse and washed it and wrapped myself in a clean overall several sizes too large. While I was escorted into their canteen my tunic and blouse went off to be dried in the boiler room and, two cups of tea later, I returned to the tram fully dressed and clean and dry again. We had to make out a full report when we reached the Depot and I was told to bring in my uniform the following day (we always had two uniforms every year). Within three days it had been replaced, but I imagined I could still smell it for ages afterwards.

That little sliding window over the platform was the only one that a passenger could open or shut himself - the rest were all wound down or up with a turning handle kept in the locker, so if someone asked for a window be opened, everyone on that side of the tram had to be consulted, as they all opened or closed together. Our passengers must be a very tolerant crowd because I don’t remember anyone objecting when I asked.

The only other story I remembered telling didn’t involve a drunk at all. We were cruising along near the Elephant and Castle one summer evening when a man dashed out of a side street just short of a request stop and ran into the road, waving to the driver who pulled up for him. As he swung on to the tram the passenger shouted, “Ring her off, mate - quick!” The reason for his state of panic soon hove into sight around the corner; a really tiny middle-aged woman in a flowered apron and man’s cap and brandishing the biggest rolling pin I’d ever seen. I had rung the tram off by then and the expression on her face, at seeing the tram pull away with her man safely on board, was really comical - she stood there, rolling pin in one hand and the other arm shaking a clenched fist till we drifted out of sight. Well, I’d seen dozens of cartoons depicting the angry wife greeting her drunken husband with a rolling pin at the ready behind the front door - but never met a woman who chased him out with one! What did he get on his return I wonder?

Another time my driver and I provided an inspector with a good story to laugh over and it came about like this. One quiet night we were cruising along with no passengers on board, my driver on this night was a jolly sort of chap whom I had worked with several times before, and he slid open the connecting door to enquire if we had anyone on board. “No - we’re as dead as a doornail,” I replied - the usual expression when referring to an empty vehicle. “How would you fancy learning how to drive?” said he. Would I - wild horses wouldn’t have stopped me - so I ran through to the front platform to receive my first - and last - lesson on driving on a tram.

Now the tram driver stands behind the control box four feet high and controls the tram with an iron lever, somewhat resembling a spanner, which is always called a “key”. This key fits around a nut on top of the box a turned through a series of notches, each notch bringing more power and thus increasing the speed of the tram. To pull up and stop, the key turns back through the notches until all power is cut off and a brake engaged and finally a handbrake is applied by turning a big wheel alongside the box. Driving a tram is as simple as that - no steering - no gears - a child could operate it. I stood there, proud as Punch, bringing a tram to a halt at every stop, becoming quite proficient in bringing it nicely in line - with the platform outside the stop - and then gliding off again - so that when we reached some traffic lights the driver even let me pull up - wait and pull away again entirely unaided while he lit a cigarette. We were some yards beyond the lights when a voice behind us remarked, “Not bad, gel - we’ll make a driver of you yet.” At least I had the sense to bring the tram to a halt, while the driver gasped and threw the cigarette over the side, then we both turned to find a Road Inspector standing behind us.

Just in case it had escaped our notice, the Inspector totted up our list of crimes while busy writing on his board: No 1 The connecting door was unlocked - No 2 The back platform was unattended on an empty vehicle - No 3 The driver was not at the controls - No 4 The driver was not in possession of the key - No 5 The conductor was driving without a licence No 6 The driver was smoking on duty and No 7 We were now (looking at his watch) four minutes late. Points Nos. 1,2 and 7 merited nothing more than a severe reprimand but Noose 3 & 4 were serious crimes and Nos. 5 & 6 were not only breaking company rules but were police offences too. We were really in trouble and no mistake. But it must have been our lucky day because, after a telling-off which lasted several minutes and left me feeling about three inches tall, the inspector showed me the board which he had been writing on while detailing our various crimes. On it he had written “Tram Correct” and told me to sign it - bound us both to secrecy and told us that if it ever happened again he would be down on us like a ton of bricks. Then he pulled a packet of fags from his pocket and gave us one each! “Just got back from hospital,” he said, “Our first and it’s a boy - after fifteen years wed!” So it was his lucky day too! He jumped my tram several times after that and neither of us ever mentioned the night his first child was born and I drove the tram. That boy must be thirty-five years old now, although that makes me very ancient indeed.

Contributed originally by Harrysgirl (BBC WW2 People's War)

A few years ago I recorded several conversations with my parents about their lives. My mother was the daughter of a stevedore who worked at Surrey Docks. She was 16 when war was declared, and she spent the war years in Deptford, London, with her father and sisters. She is now aged 81. What follows is her account of her experiences during the war, which I transcribed from the tapes.

Daisy's War

When the blitz started when we were living in a terraced house in Greenfield St. in Deptford, and we had to have an Anderson Shelter built in the garden. The workmen brought it and they dug the hole and installed the shelter. Half of it was above the ground, but the floor was about four feet below ground. They fitted some benches, which were most uncomfortable, and water seeped in from the ground making it soaking wet most of the time, but we slept down there nearly every night throughout the blitz in 1940-41. At one time we didn’t even wait for the air raid sirens to go off because the raids were nearly every night.

There were an awful lot of houses damaged, and many of those that were not flattened had to be demolished because they were unsafe. When we went up the high street in the morning after a raid there were plenty of shops that had been hit and the big factory where they made parts for fire engines, was destroyed. The Surrey Docks were not far away, and one night they were badly hit. We could see the sky all red from the fires. My brother, Stan, had a friend who was in the auxiliary fire brigade and he got killed that night on the docks. It was very sad - his mother had already lost her other two sons and her husband to tuberculosis. On Blackheath, outside Greenwich Park gates, there used to be a huge hollow where the fair was set up every bank holiday. During the war they filled it right up with the rubble of the buildings that were destroyed, and now that part of the heath is flat.

Most of the raids were after dark. We didn’t always go down the shelters, but it was so tiring if the air raid warning went in the night. We three girls slept in one room downstairs. I was always on the end and I had to go tearing up the stairs to wake my father up and tell him that the alarm had gone, because he was deaf and didn’t hear the siren. Then we’d all go down the shelter. It was horrible to be woken like that night after night, and really tiring. We had a dog at the time and he soon learned what the sirens meant. For daytime raids, as soon as the back door was opened he ran out to be the first one down, and at night he slept there. Sometimes he took his bone down and woke us up gnawing away at it. Then we’d kick him to make him leave the bone alone.

The worst period was during the blitz, which lasted for 6 or 9 months overall. As the Battle of Britain went on the RAF knocked a lot of the bombers out of the sky, and then things were a bit better. On Blackheath there was a huge anti-aircraft gun called Big Bertha, which used to belt out at night, with batteries of searchlights trying to pick out the bombers. The searchlights all over the sky at night were spectacular to watch, until the sirens went: then we ducked down into the shelter. My father was usually the last one down, as he was deaf and stayed outside looking up at the sky, oblivious to the shrapnel falling all around and hitting the shelter roof. We had to shout at him to come down in case he got a lump of it on his head. I suppose quite a few people must have got killed with shrapnel.

The Air Raid Wardens were very hot on lights, and we dared not have even a streak of light showing through the curtains. Even outside there were no lights: patrolling wardens would shout “Put that fag out” if we so much as struck a match. We were allowed to use torches, but we had to be sure they were directed towards the ground. When we went out it was pitch black at night, all the lights were off and you had to have a torch in the winter.

Despite the bombing and the blackout we still went out in the evening during the war. We went up the West End sometimes on the Underground, where people spent the night if they had no air raid shelter. I first saw “Gone with the Wind" in the West End. If the air raid sirens went off while we were in the cinema the film just carried on -we never left. Strangely enough we weren’t frightened; maybe a bit wary, but not really frightened. Sometimes you could hear the bombs going off outside, but after a while we ignored it, more or less. We had guns from the cowboys going off inside and bombs going off on the outside. A lot of people got killed that way, especially in night clubs, by not leaving during the air raids.

If we were caught in the street during a raid, it was a different matter – we ran for the nearest shelter. We always ran for cover if we were outside. In Deptford High Street there was a bomb shelter under a big shop- Burton’s, a clothing shop. Everyone out in the High Street when the sirens went off ran for that, and stayed down there until the “all clear” sounded. Most of the raids were at night, and in the morning on the way to work we could see what the bombs had done . The did a lot of damage - knocked down buildings, shops and everything, but Burton’s was never knocked down. There were some American troops in the area and they used to help with clearing up the bomb damage. By the time the war ended most streets around Deptford and Lewisham had buildings missing where the bombs had landed. It was amazing really that we came through it all. I’ve heard it said that the people who stayed at home suffered worse that the men who were in the army in some areas. The civilians took the brunt of it all.

Towards the end of the war my Aunt Martha moved to Adolphus Street, and there was an empty house next door and this one had 3 bedrooms. So we packed up our stuff and moved next. Although the war was coming to an end, there were still air raids and the Germans also sent over the “V” weapons, doodlebugs, mostly during the day. There were no warning sirens for those: the buzz would get louder overhead the bombs could be seen going through the air with a flame coming out of the end. The only time we were wary was when the noise stopped . Then we ducked for cover, because when the engine stopped the bomb was going to come down.

Once in Adolphus Street, when I was 19 or 20, I was sitting at home with my father when there was an almighty bang. I got down on the floor and my father got down on top of me to cover me up and we stayed there for a little while. When we got up the windows were all gone and the ceiling was down. There had been a land mine - they used to come down on parachutes - at the bottom of the street and 22 people were killed that night . All the houses round about had lost windows and some had their doors blown off. All our bedroom and living room windows went . We went to see what had happened after the “All Clear” sounded: it was dreadful to see the bodies lined up in the street waiting for the ambulances to take them away. We got off lightly by comparison: we were given dockets to get our sheets and curtains replaced and because the war was still on they came round and boarded over the windows. We had no daylight in the house for a while, until we could get the glass replaced.

Rationing

I wish I’d kept a ration book. We were rationed to an ounce or two of cheese a week, there was a sweet ration, and a meat ration. It was impossible to buy an egg during the war. I don’t know why- there were plenty of new laid eggs in the shops before the war, and the hens must still have been laying, so I suppose the eggs went to the troops. The rest of us bought egg powder which was mixed with a bit of pepper and salt and milk, and whisked in the frying pan like an omelette. Bread and potatoes weren’t rationed, but everything else was. Almost everything we bought, including clothing, we had to give up coupons, and there were dockets to allow replacement of bedclothes and other things destroyed in the raids. The only new furniture that was made was ”Utility” furniture, which was well made of good wood, but of a very plain and economical design. The manufacturers were not allowed to make anything else. Rationing continued for a long time, even after the war was over. In fact rationing of a few things lasted into the 1950’s.

Contributed originally by EileenPearce (BBC WW2 People's War)

All the control staff were issued with full uniforms. We had from the beginning worn navy blue skirts and white blouses, but now to these were added navy battledress tops and, finally, overcoats and a smart cap. I didn't like wearing uniform particularly, but, as it was difficult to dress at all, let alone well, with the aid of the clothing coupons ration, the C.D. clothes were a great help, and definitely undemanding, as one was not required to look different from others, but rather the reverse.

Time progressed, and for a long time it seemed as though the good news hoped for would never come. At least the B.B.C. could be trusted in the main not to issue lies instead of news, but this meant that there was little to cheer us from the war front.

It was a very exciting moment when, late one night, the news came through of the success in North Africa, the first big success we had heard of. Our shift was just coming off duty at 11.30 and I remember running upstairs, through the old Town Hall across to the new building, downstairs to the basement and into the canteen to spread the tidings. How terrible that battle, slaughter and misery could give such a lift to the morale at home!

Work in factories and everywhere else was constantly interrupted by air raid warnings, when employees had the right to stop work and take shelter. Often, however, the bombers giving rise to the warning were still far away. The public warning system was a very blunt instrument, driving underground thousands of people in no immediate danger, and keeping them there twiddling their thumbs when they would have been better employed getting on with their work.

To meet this difficulty a system called the Alarm Within the Alert was devised, and the Civil Defence Control staffs in the Metropolitan Boroughs of London were in some cases, Lewisham being one, entrusted with the working of it. Installed in our Control Room, it consisted of a writing table with a large map of south-east England propped up on it, covered by Perspex.

This material had never been seen before, and its great virtue, as everyone now knows, was that it could be written on with the appropriate stilus and the writing rubbed off easily with a duster.

Beside the map was a telephone directly connected to a gun site somewhere on Blackheath. On the other side of the map was a push button bell, which was connected to twenty or more factories in the district. The Blackheath gunners were, of course, in communication with the Royal Observer Corps on the Coast, our first and vital defenders who, with the aid of their binoculars, kept vigilance at all times. They were still needed, even after the invention of radar, the next line of defence.

When enemy aircraft approached the coast, our direct line would ring, and we in the Control Room would be connected so that we were eavesdropping on the "plots" passed to the site, from the Observer Corps or Radar, for the Ac Ac gun to be fired with the correct range and bearing. From these plots we indicated the course of the enemy on the map. This was quite an exciting addition to our more humdrum duties, and, though we all had to train to know what to do, Tiddles and I were soon the usual two on our shift to cope with the Alarm within the Alert System, soon called "the Hushmum", as we were sworn to secrecy as to its existence and purpose.

Required secrecy about matters of this kind came under the Official Secrets Act, Clause 18B, (but I have no idea to what clauses 18A or indeed 18C might have referred).

This Alarm within the Alert System caused quite a flutter among the people on the Local Authority Staff who provided the greater part of the Civil Defence Control. There were ten groups of/ about a dozen people culled from the staff in the Town Hall, Libraries and other establishments situated near the Control Room, and each group was on duty one day in ten, a "day" being twenty-four hours. Each group had an officer-in-charge drawn from people in a senior position on the staff. The Civil Defence Controller for the Borough was the Town Clerk, and the Deputy Controller was the Deputy Town Clerk. The Message Room staff to which Joanna and I belonged saw the clock round in eight-hour shifts, and dealt with the day-to-day happenings between air raid warning times, as well as being on duty during alerts. When the Officer-in-Charge was in the Control Room, we were responsible to him.

The Stretcher Parties also came under the Borough Council, but the Heavy Rescue was the responsibility of the London County Council, and the Officers were mostly Architects, like Adrian, seconded from the L.C.C.'s Architectural Department, or, alternatively, Engineers.

The Alarm Within the Alert was outside the ordinary Civil Defence system, and came under the Ministry of Defence, so that the Town Hall Shifts were not initiated into its mysteries. There it was installed in a corner of the room, but they were supposed to look the other way and not ask questions. I cannot think it was so very secret, but no one ever questioned us about it, and we never told anyone anything.

There were circles drawn on our map of the southeast, one far out over Surrey and Kent, and another tightly in around Lewisham and neighbouring Boroughs. When the telephone bell rang the two allotted the duty sprang to it and seated themselves at the table with the map before them. This map was covered with newly invented Perspex on which the plots were drawn and could easily be rubbed off with a duster. Tiddles (Doreen Chivrall) and I were the usual pair to perform this duty on our shift, as Nicky (Ann Nicholson) was the senior one of our shift of four, and Frankie (Olive Leonard) though charming, willing and extremely ornamental was far from swift in her reactions when plots came thick and fast. We all had some training in converting the plots into arrows on the map, but some of us were quicker than others.

Incidentally, (Oh, Women's Lib!) it had been found that the girls were rather quicker than the boys when tests of speed in these tasks had been made, or so we were told by our instructor.

The map was, I suppose, the ordinary kind used in military circles, and was divided into large and small squares. Each enemy aircraft was given a number which came first over the direct line followed by the ominous term "Hostile", and this was followed by a combination of letters and numbers, together with a direction (N.E., N.W., or whatever) enabling us to pinpoint the position of the aircraft and its direction and to draw an arrow appropriately. Once a plot crossed the outer circle we were on the qui vive to give the alarm to our factories by pressing the push button wholeheartedly and long should the inner circle also be penetrated.

We both wore headphones, one of us entering the plots in a book and the other inserting the arrows on the map. The tension eased slightly once the alarm had been given, but, on the other hand, it increased in that we knew the enemy was more or less overhead, and we would often feel the vibration if something fell not far away, and even hear the drone of the bomber's engines if it passed near enough, in spite of being underground.

Of course, we were given plenty of practice with our new toy by being connected to the gunsite when they had time to carry out exercises, and these dummy runs were always prefixed by the word "Exercise." Tiddles and I were plunged in at the deep end when the installation in the Control Room was completed. The electrician had just connected the last wire and we were all, including Mr. Alan Smith, the Controller, standing round admiring the pristine map and general set up, when the bell rang. Tiddles and I had been designated for that day's duty, so I picked up the receiver and heard "Hostile" - followed by a plot, "Hostile", I squeaked, and, before we knew where we were, we were madly plotting and writing in an area unexpectedly close to our Lewisham boundary. Within a few seconds the first aeroplane had penetrated our sacred circle, swiftly followed by four or five others.

We pressed our button, but there cannot have been more than the briefest of warnings before the bombs were dropping. We did, however, beat the public system, as the air raid sirens were sounded only after the bombs were dropped.

What had happened was this: about half a dozen German planes had come in over the coast, where I suppose they had been reported by the Observer Corps, but they had then descended to a very low level so that they had got below the Radar, and, daringly, they had hedge hopped all the way to South London.

By the time we received our first plot, which may well have come from the Observer Corps, they were almost upon us. They were, of course, flying below the barrage balloons, almost at roof height, and we heard the roar of the engines.

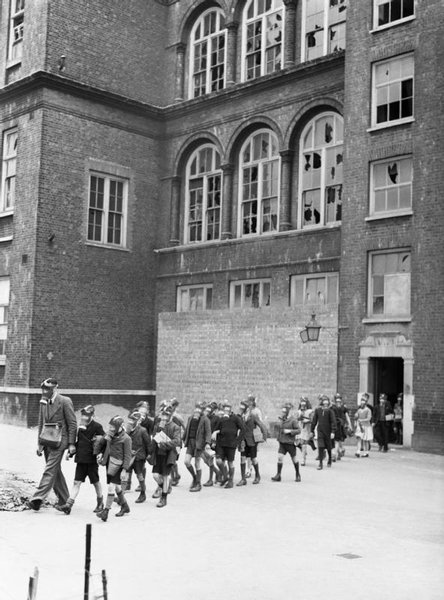

Although there were no casualties in "our" factories, who duly received our first ever warning just in time to scram, this was for Lewisham a tragic raid, as there was a direct hit on the primary school in Sandhurst Road, near the Town Hall; forty-seven children and three teachers were killed, and many injured. As there had been rather less aerial activity for a time since the early blitz, many parents had decided to bring their children back from the evacuation areas, otherwise no doubt the casualties would have been fewer, but it is easy to be wise after the event.