High Explosive Bomb at Beacon Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Beacon Road, Hither Green, London Borough of Lewisham, SE13, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by nationalservice (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was added to the site by Justine Warwick on behalf of Alan Tizzard. The author is fully aware of the terms and conditions of the site and has granted his permission ofr it to be included.

This is the story of how wartime stole my childhood and forced me to become a man

Saturday the 7th September1940 was a glorious summer day. I was 10-years-old, sitting in the garden of my parents home in Hither Green Lane just off Brownhill Road, caught up in the knock-on effect of the teacher shortage at Catford Central School in Brownhill Road and attended mornings one week and afternoons the next.

This was the case for those of us whose parents would not be parted from their children, or whose wisdom suggested something was fundamentally wrong with evacuation to destinations in Kent or Sussex. Surely these places were nearer the enemy across the Channel?

Anyway, I was at home with my mum, dad and older brothers and sisters and it was great!

My dad, because, he was a Lighterman and Waterman on the Thames and had been a policeman, found himself on the fireboats patrolling the river to

put out fires caused by enemy planes. My brother-in-law Jim was in the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) stationed in a nearby school. He drove a commandeered London taxicab that towed a fire pump trailer. Brother Ted was a peacetime Royal Marine, serving on HMS Birmingham. Brother Chris, at 16 years was crazy on American gangster films and used to make wooden models of tommy guns they used. He encouraged me to make model aircraft from the Frog Model kits of those days.

On that sunny Saturday afternoon in early September I was sitting on the kitchen step whittling away at my model when the sirens sounded. No sooner had the sirens stopped than the fírst planes came into sight. They were high, by the standards of the day, maybe twenty thousand feet. Hurricanes and ME109's. They were twisting and turning, weaving and bobbing. To me this was a grand show. So far my sight of war had been at a distance and knocked the cinema version into a cocked hat.

Suddenly what had been a spectator sport, not wholly real changed to War. I was to leave childhood behind forever.

From the front of the house we did not see the approach of that part of Luftflotte Zwei from across the Channel as they came from behind us. A sudden shower of spent machine cartridge cases rained down all around us. What had been the relatively dull ever-changing drone of the fighters in dog-fights high above our heads with their guns making no more than a phut, phut changed to pandemonium. The stakes had changed. We were now a part of it.

Chris said: "I think they're trying for the bridge." As he spoke, a Heinkel 111 flashed into sight coming in at an angle from our right. I believe it was being chased by a fighter as another shower of empty cases came down, bouncing and pinging on the front garden paths and pavements. Suddenly an aerial torpedo fell away from the Heinkel, which seemed to bounce higher into the air as the weight of the missile fell clear. The Heinkel disappeared, climbing away to its right out of our sight. Some seconds later we heard the explosion.

Two.

Later, in a conversation, my brother-in-law t the AFS man stated the showrooms had copped it from an aerial torpedo. From his comments and the first hand observation of my brother and myself that afternoon, I believe the Heinkel 111 we saw was the culprit.

I am not sure. But this much I know that was the day I stopped being a little

boy. I think it was seeing German planes still managing to fly in formation not withstanding all that the Hurricanes were doing to try to stop them, that took away my innocence.

Two days later, on the afternoon of Monday September 9,I answered a knock at the front door of my parents' home and was taken aback by the spectacle of a man so covered in oil and filth from head to foot that I didn't at first recognise my brother-in-law. Jim the firefighter had gone on his shift on the afternoon of 7th and had only then returned. Calming my alarm at his state, Jim explained that his unit had been in I he docks fighting fires

for over 72 hours and that at one point had been blown into the oil-covered waters.

The filth laden atmosphere pervaded the air for days. The sky to a great height wreathed with smoke of all colours that glowed red, orange and in some places blue.

Soot seemed to fall contínually and as you wiped it away it smeared your hanky and smelt of oil.

On the afternoon of the 11th September the sirens went again. We were all getting very weary from the raids, Í was little more than a young child and I had, had enough. I can't imagine what it must have been like for the grown up members of my family. ^^^H

Certainly, we had by now we had given up trying to brave it out when the bombing got local. So my mother, two sisters, my brothers Chris and Arthur and Jim, all climbed into the Anderson shelter in the garden.

Usually the doors were pretty firm. But things were really getting hot outside. All hell was going on out there

The door was hammering against the shelter and coming loose - at one point Jim leapt forward and simply held on while I was pushed to the floor and my sister Maisie threw herself on top of me As I lay pinned down I could see Jim rocking to and fro at each blast from outside.

I don't know when, but in due course things became quieter, and Jim climbed out. I don't recall actually leaving the Anderson, but I do

remember what 1 found outside. My mother's orderly wartime garden, her pride and joy, was a wreck. The back door to the house 'was laying in the yard. All the rear windows were gone, where the frames had survived shreds of what had been net curtains hung in tatters.

The whole house was in tatters. The road outside was a shambles, everywhere were those empty cartridge cases. Arthur and I started collecting them looking to see if they were theirs, or ours. Over on the other side of the road, a showroom was burning, soldiers were milling around some kind of control vehicle with a dome on top painted in a chequer-pattern. I believe they must have been bomb disposal chaps.

Three.

I remember later, in the back garden my brother Arthur endeavours to chop with a garden spade the burnt half of an otherwise un-burnt incendiary bomb that he had found in the front garden.

The whole thing had an unreal feeling about it. It was then that my family moved.

I have no recollection of any decision being taken by my elders to leave the house. I do recall being in the back of what must have been a 15-cwt Army lorry with some but not all of my family. The vehicle bumped away from our house and as I looked through the back I was being cuddled by my older sister Maisie. The sky was yellowy and smoky. Opposite and to the left of our house five houses had five houses had their upper floors torn away, our lovely Methodist Church and my cub scouts' hall had totally disappeared.

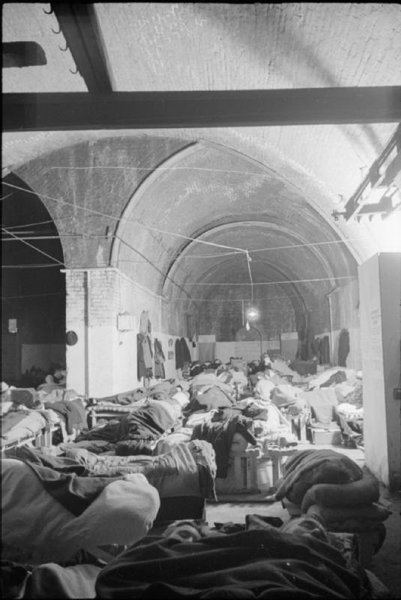

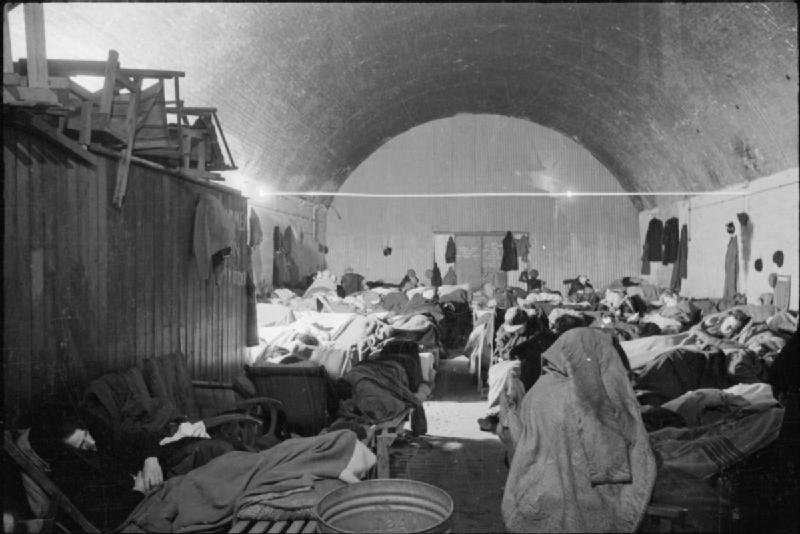

The 15-cwt turned left into Wellmeadow Road and made its way to the rest-centre at Torridon Road School where we remained until the 15th September before temporary evacuation to Sutton-in-Ashfield Notts. We returned to Bomb the Alley of southeast England after a short respite and I regarded myself as grown-up for the remainder of the war.

NB:This article written by me appeared in The Greenwich Mercury November 28th1996.

The article was accompanied by two photographs one of me in my parents wartime garden of the house from which we were bombed out shortly after it was taken.

The other photograph was taken in 1954 following my return to England having been in the Occupation Army in Germany.

The little girl in one of the pictures was Joyce Eva Maycock of Hampton Village, Evesham, Worcestershire a sweet little thing from the country not realising she would later marry the urchin above. (as I write this Tuesday, August 03, 2004 come tomorrow Wednesday 4th August 2004 we shall have been married fifty years)

Contributed originally by Marian_A (BBC WW2 People's War)

Gladys’s Diary 1940, cont.

2/10/40 Was just about to sally forth this morning when the siren sounded. A bomb dropped over the green, just as I was near, in Brookhouse Rd. Bricks hurtled around me. I rushed across and took cover in Anderson shelter of a house opposite. “All clear” went half-hr. later, only to be followed by a siren a few minutes later. Took shelter in the same house till 11 o’clock. About 3 people were killed in the house including two women Mum knows. I eventually got to work at 11.45…Left office at 4.30 in a raid warning. Got home about 5.30. Siren sounded at 7.45 p.m.. Final “All clear” about 6.15 a.m.

4/10/40 Today was a terrible one. Nothing happened until lunchtime, when the siren went, just before one o’clock. During the afternoon we had to go to the shelter once or twice. Miss B went about 4.30, and I stayed to finish a letter…I had to go to the shelter twice again. Eventually I set off home at 6.15 during the warning, another having sounded after the “All clear” at 5.45. During my train journey the second “All clear” and a third warning sounded! This last proved to be the all night one — I went straight in the shelter when I got home, emerging only at 11 p.m. during a lull in the firing to change and get some food, which we ate in the shelter.

7/10/40 There was no raid during the night, and when Dad came home [from his night shift job] just before 5 a.m. we went in to bed. However, there was a warning at about 6 a.m., so Mum and I returned to the shelter. Another warning sounded while I was on the train, but nothing happened (to me!) Various warnings occurred, and once we adjourned to the shelter. I was very busy all day and did not leave the office until 5 during a warning. The “All clear” went as I crossed over to the station. Didn’t get home till half past six. Just had dinner and changed when the siren sounded at 7.40 approx.

8/10/40 The raid alarm sounded this morning about 8.45, and the “All clear” about 10 a.m. When I set out for work Mum, who was going to the shops, came with me. We got caught in two more alarms, during the first of which we sheltered in an Anderson shelter at the invitation of some workmen, and in the second we went into a public shelter. I eventually reached the office (in the middle of a fourth alarm!) at 12.45!

13/10/40 (Saturday) After breakfast Arthur put in some more work on the air raid shelter. While I was having my bath, the siren went, and just as I’d dried all of me except my feet, and was clad only in vest and knickers, I heard bombs descending. Just as I was I ran down and dived beneath the stairs! Luckily Arthur was in the garden and so did not witness my undignified descent.

14/10/40 Heard this morning that last night’s raid was very bad, with many casualties…

16/10/40 Had lunch in office. Walked to Cheapside and found, much to my joy, that some shops, including Woolworths, are open again. …Found everyone in a profound state of depression at home. Siren went about 7 p.m.. Mum very depressed in the shelter…

17/10/40 This morning there were two warnings before I set out for the office, and I eventually got a train about 11.20! …Arthur phoned … he is O.K., thank God, but said about 90 bombs were dropped in this district in recent night raids. Caught a train from Holborn during a raid. Had to leave the train between Catford and Bellingham and walk back along the line to Catford, whence I travelled to Southend Lane by lorry! Bellingham signal box has been damaged by bomb. Siren went just before 7. Heaps of bombs dropped.

19/10/40 (Saturday) I did my various jobs this morning and got ready for Arthur, but he was very late. Planes were about terribly, but no raid occurred…Arthur did not arrive until 5 o’clock … he’d had to stay to H.G. [Home Guard] rifle drill. I felt so very relieved to see him. He’d some sandbags for the shelter and we went down to the shops to get some creosote for them, and Arthur was still covering the bags with it when the siren went.

21/10/40 Had day of warnings and had to take shelter several times. Took from 4.15 till 6 p.m. to get home. Siren went at 7.10, but we heard gunfire and planes earlier, and were already in our dugout.

25/10/40 Had two bombs drop this morning before sirens went, and afterwards there was a very great noise of diving planes, and more bombs dropped. After the “All clear” Mum and I sallied forth to Bellingham wireless shop, and I purchased a portable set, on weekly terms, for the air raid shelter. Carried it home part of the way, and met Dad who took it the rest…Had pretty bad raid tonight but the wireless “took it off”.

26/10/40 (Saturday) Had a lot of air raids, and took cover once or twice, and by the time I’d done my various tasks it was late, and I didn’t reach Arthur’s until about

3 p.m….We sat and talked, and then had tea. Soon it was “siren time”, and we went into the shelter, Arthur first rescuing a white dog which had somehow got shut up in an upper room of a derelict house opposite. Arthur and Mrs B [Arthur’s mother] played cards and I knitted. We packed down about 10 p.m.

28/10/40 …I felt very tired and depressed. Jolly old siren went at much the usual time. Things were “pretty hot”, but I felt very cold. Didn’t do any knitting. Accumulator had packed up so no wireless. Just sat and listened to the guns etc…

31/10/40 …Arrived home about 5.30. It’s been a dreadful day, pouring with rain. I was drenched. The siren went very early, just after 6.30, and I’d had to put my hair in curlers in the dugout…

10/11/40 …No day alarms at all…

12/11/40 The siren went at about 6.45 p.m. A bright moon shone, and there was very, very heavy gunfire.

14/11/40 Planes zoomed about a good deal this morning, but nothing happened…got home about 5.15. Scoffed my tea, then washed my hair. Was all ready for the shelter when the siren went; as a matter of fact we were there already, as we’d heard planes and guns.

16/11/40 …The time bomb in Elfrid Crescent went off just as we were at the Post Office. Nobody hurt, but we had some windows broken and I had to clean my bedroom floor, more bits of ceiling having fallen…

18/11/40 We were awoken by terrible bomb explosion at 4 a.m. It blew our lamp out…Didn’t go out lunchtime as it became dark and poured with rain. Continued so all the afternoon…The siren didn’t sound till 8.15, but as it was a cold, dark night and the shelter was warmer than the kitchen, we went down there about 7.30.

17/12/40 …As there was no warning, we stayed indoors tonight.

25/12/40 (Christmas Day) After a peaceful night, we got up fairly early, and had our breakfast. We lit a fire in the front room in honour of the day. I did the usual tidying up etc., and heard a broadcast featuring evacuees in Wales, including Datchelorites [girls from Mary Datchelor, Grace’s school] and there was a special message to Joyce Davies, Grace’s friend who is in hospital. After dinner I sat in the parlour and opened my presents… After tea we played “Bombardo” and listened-in. No air raid occurred.

27/12/40 The air raid warning went about 7. It was such a bad raid that we couldn’t get to the dugout. We went under the stairs twice. A bomb fell on the allotment by Dr Wallace’s house, badly damaging it and several other houses around. I dragged Gran under the stairs when I heard it falling, and knocked her head! She made a dreadful fuss. Just after we managed to get to the shelter a shower of incendiaries fell.

29/12/40 …The siren went very early, at just after six, and there was a terrible raid. I felt very frightened, and Arthur was very sweet and kind. Poor Dad had to go out in it. Arthur got Gran down to the shelter... We went back to the house before going to sleep, and saw the red glow of a great fire in the sky…

30/12/40 …Our trainline is out of order, so I travelled to Cannon Street from Catford Bridge. Saw devastating scenes in the City. All along Cannon Street & Queen Victoria Street fires are still burning, and a ring of fires is round St. Pauls. St. Brides and St. Andrews-by-the-Wardrobe are gutted — also Guildhall. Fires rased also both sides of Cheapside and in Ludgate Hill etc. Everywhere in fact. Felt very miserable when I saw it all…

31/12/40 Had difficulty getting to the office. Got train to Charing Cross, and walked thence to the office, there being still no buses in the City. Fires were still burning… The Home Secretary broadcast an appeal for fire watchers. Some neighbours who are organising such a local service called, but Dad being on nightwork , he’s no good. I offered, but they only want men. No siren had sounded up to 9.40 p.m.

Contributed originally by EileenPearce (BBC WW2 People's War)

All the control staff were issued with full uniforms. We had from the beginning worn navy blue skirts and white blouses, but now to these were added navy battledress tops and, finally, overcoats and a smart cap. I didn't like wearing uniform particularly, but, as it was difficult to dress at all, let alone well, with the aid of the clothing coupons ration, the C.D. clothes were a great help, and definitely undemanding, as one was not required to look different from others, but rather the reverse.

Time progressed, and for a long time it seemed as though the good news hoped for would never come. At least the B.B.C. could be trusted in the main not to issue lies instead of news, but this meant that there was little to cheer us from the war front.

It was a very exciting moment when, late one night, the news came through of the success in North Africa, the first big success we had heard of. Our shift was just coming off duty at 11.30 and I remember running upstairs, through the old Town Hall across to the new building, downstairs to the basement and into the canteen to spread the tidings. How terrible that battle, slaughter and misery could give such a lift to the morale at home!

Work in factories and everywhere else was constantly interrupted by air raid warnings, when employees had the right to stop work and take shelter. Often, however, the bombers giving rise to the warning were still far away. The public warning system was a very blunt instrument, driving underground thousands of people in no immediate danger, and keeping them there twiddling their thumbs when they would have been better employed getting on with their work.

To meet this difficulty a system called the Alarm Within the Alert was devised, and the Civil Defence Control staffs in the Metropolitan Boroughs of London were in some cases, Lewisham being one, entrusted with the working of it. Installed in our Control Room, it consisted of a writing table with a large map of south-east England propped up on it, covered by Perspex.

This material had never been seen before, and its great virtue, as everyone now knows, was that it could be written on with the appropriate stilus and the writing rubbed off easily with a duster.

Beside the map was a telephone directly connected to a gun site somewhere on Blackheath. On the other side of the map was a push button bell, which was connected to twenty or more factories in the district. The Blackheath gunners were, of course, in communication with the Royal Observer Corps on the Coast, our first and vital defenders who, with the aid of their binoculars, kept vigilance at all times. They were still needed, even after the invention of radar, the next line of defence.

When enemy aircraft approached the coast, our direct line would ring, and we in the Control Room would be connected so that we were eavesdropping on the "plots" passed to the site, from the Observer Corps or Radar, for the Ac Ac gun to be fired with the correct range and bearing. From these plots we indicated the course of the enemy on the map. This was quite an exciting addition to our more humdrum duties, and, though we all had to train to know what to do, Tiddles and I were soon the usual two on our shift to cope with the Alarm within the Alert System, soon called "the Hushmum", as we were sworn to secrecy as to its existence and purpose.

Required secrecy about matters of this kind came under the Official Secrets Act, Clause 18B, (but I have no idea to what clauses 18A or indeed 18C might have referred).

This Alarm within the Alert System caused quite a flutter among the people on the Local Authority Staff who provided the greater part of the Civil Defence Control. There were ten groups of/ about a dozen people culled from the staff in the Town Hall, Libraries and other establishments situated near the Control Room, and each group was on duty one day in ten, a "day" being twenty-four hours. Each group had an officer-in-charge drawn from people in a senior position on the staff. The Civil Defence Controller for the Borough was the Town Clerk, and the Deputy Controller was the Deputy Town Clerk. The Message Room staff to which Joanna and I belonged saw the clock round in eight-hour shifts, and dealt with the day-to-day happenings between air raid warning times, as well as being on duty during alerts. When the Officer-in-Charge was in the Control Room, we were responsible to him.

The Stretcher Parties also came under the Borough Council, but the Heavy Rescue was the responsibility of the London County Council, and the Officers were mostly Architects, like Adrian, seconded from the L.C.C.'s Architectural Department, or, alternatively, Engineers.

The Alarm Within the Alert was outside the ordinary Civil Defence system, and came under the Ministry of Defence, so that the Town Hall Shifts were not initiated into its mysteries. There it was installed in a corner of the room, but they were supposed to look the other way and not ask questions. I cannot think it was so very secret, but no one ever questioned us about it, and we never told anyone anything.

There were circles drawn on our map of the southeast, one far out over Surrey and Kent, and another tightly in around Lewisham and neighbouring Boroughs. When the telephone bell rang the two allotted the duty sprang to it and seated themselves at the table with the map before them. This map was covered with newly invented Perspex on which the plots were drawn and could easily be rubbed off with a duster. Tiddles (Doreen Chivrall) and I were the usual pair to perform this duty on our shift, as Nicky (Ann Nicholson) was the senior one of our shift of four, and Frankie (Olive Leonard) though charming, willing and extremely ornamental was far from swift in her reactions when plots came thick and fast. We all had some training in converting the plots into arrows on the map, but some of us were quicker than others.

Incidentally, (Oh, Women's Lib!) it had been found that the girls were rather quicker than the boys when tests of speed in these tasks had been made, or so we were told by our instructor.

The map was, I suppose, the ordinary kind used in military circles, and was divided into large and small squares. Each enemy aircraft was given a number which came first over the direct line followed by the ominous term "Hostile", and this was followed by a combination of letters and numbers, together with a direction (N.E., N.W., or whatever) enabling us to pinpoint the position of the aircraft and its direction and to draw an arrow appropriately. Once a plot crossed the outer circle we were on the qui vive to give the alarm to our factories by pressing the push button wholeheartedly and long should the inner circle also be penetrated.

We both wore headphones, one of us entering the plots in a book and the other inserting the arrows on the map. The tension eased slightly once the alarm had been given, but, on the other hand, it increased in that we knew the enemy was more or less overhead, and we would often feel the vibration if something fell not far away, and even hear the drone of the bomber's engines if it passed near enough, in spite of being underground.

Of course, we were given plenty of practice with our new toy by being connected to the gunsite when they had time to carry out exercises, and these dummy runs were always prefixed by the word "Exercise." Tiddles and I were plunged in at the deep end when the installation in the Control Room was completed. The electrician had just connected the last wire and we were all, including Mr. Alan Smith, the Controller, standing round admiring the pristine map and general set up, when the bell rang. Tiddles and I had been designated for that day's duty, so I picked up the receiver and heard "Hostile" - followed by a plot, "Hostile", I squeaked, and, before we knew where we were, we were madly plotting and writing in an area unexpectedly close to our Lewisham boundary. Within a few seconds the first aeroplane had penetrated our sacred circle, swiftly followed by four or five others.

We pressed our button, but there cannot have been more than the briefest of warnings before the bombs were dropping. We did, however, beat the public system, as the air raid sirens were sounded only after the bombs were dropped.

What had happened was this: about half a dozen German planes had come in over the coast, where I suppose they had been reported by the Observer Corps, but they had then descended to a very low level so that they had got below the Radar, and, daringly, they had hedge hopped all the way to South London.

By the time we received our first plot, which may well have come from the Observer Corps, they were almost upon us. They were, of course, flying below the barrage balloons, almost at roof height, and we heard the roar of the engines.

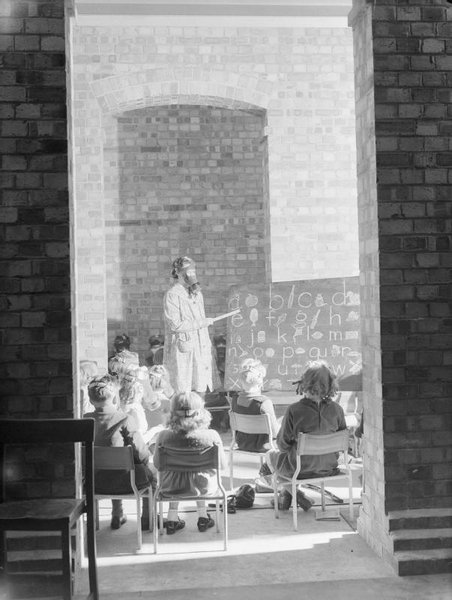

Although there were no casualties in "our" factories, who duly received our first ever warning just in time to scram, this was for Lewisham a tragic raid, as there was a direct hit on the primary school in Sandhurst Road, near the Town Hall; forty-seven children and three teachers were killed, and many injured. As there had been rather less aerial activity for a time since the early blitz, many parents had decided to bring their children back from the evacuation areas, otherwise no doubt the casualties would have been fewer, but it is easy to be wise after the event.

Contributed originally by Thurza Blurton (BBC WW2 People's War)

SOME MEMORIES OF MY WAR

I have a store of memories of the second world war. Here are a few of the most unforgettable.

When the war started, I lived in Lewisham, South East London, with my parents and older sister, Connie.

She and I were 'called up' for war work. And Dad volunteered for the A R P (Air Raid Precautions). He was a Member of the Light Rescue Division. This was responsible for administering first aid to the injured after they had been dug out by the Heavy Rescue. Dad had a terrific sense of humour and kept us and those around from going insane, by the funny things he said.

Mum did as much for the war effort as the rest of us. Like many other mums, who kept the 'home fires burning,' so to speak. She always had a hot meal ready for us when we got home, which had to be eaten quickly before the Sirens sounded, warning us of approaching enemy aircraft. We'd have to run down to the Anderson air raid shelter in the garden, which was affectionately called - 'the dug-out.'

Sirens sounded. Some nights (and days) if the warning went while we were having a meal we'd pick up our plates and hurry down to the shelter with them.

On one particular occasion, though terrified, Mum made us laugh by putting the plate on top of her head to protect it from the bombs.

Dad was on duty at Greenwich one night and we other three and our Scotch terrier, Judy were in the 'dug out,' Bombs were dropping fast and furious. They were chucking everything down that night. 'even iron bedsteads,' Dad said afterwards. Which reminds me of when the government confiscated all the iron they could lay it's hands on for the war effort. They took the railings from the front of our houses. I don't think any of them were replaced.

But as I was saying, on this particular night, the three of us were chatting in the shelter. We talked about this and that to try and take our minds off the bombing. Mum told us what had been happening that day. In the afternoon there was a raid including incendiary bombs. Mum went to the front door to see if any passer-by wanted to come in until the ALL CLEAR sounded when an incendiary landed on the doorstep. Mum picked it up hoping to throw it into the road, (I don't think she intended to chuck it back up!) but an Air Raid Warden shouted at her, "Put that 'bleepy' thing down, you silly 'bleeper'". Mum dropped it, rushed indoors and shammed the door. Luckily, the bomb didn't flare up, but burnt a hole in the doorstep, where it remained until the house was bombed all together. But that's another part of the story.

Anyway we had a good laugh when Mum told us all about it.

Another night we were in the shelter when heavy bombing was in progress. Suddenly Connie screamed.

Mum said, "Don't worry love, we're all here together. (Meaning if we got killed, we would all go together).

"It's not that," Connie cried pointing to the pile of blankets which served as our communal bed, "There's a mouse in there." To say we were terrified, was putting it mildly. We scrambled through the opening of the shelter and stood leaning against it, too afraid to stay inside with the mouse. We stuffed our fingers in our ears, because the noise was more deafening out in the open.

Dad found us there when he came off duty.

"What are you doing out here you silly 'bleepers,?' he asked, "It's not safe, get back inside."

"There's a mouse in there," we said in unison.

Dad got rid of it and we all scrambled back into the shelter. Dad said, "If Hitler had dropped a load of mice instead of bombs, he'd have won this 'bleepy' war."

Dad used to tell us what happened while he was on active duty; not the really bad things, though there were plenty of those; like how, who and where they'd been killed. One night, Dad was attending to a wounded family who'd been rescued from it's demolished Anderson shelter.

Dad tried to comfort an elderly lady. "Don't worry love," he said, you'll be alright, the ambulance is here."

"My leg, my leg," she cried, "Where's my leg."

Dad called to one of the other men, "Tourniquet wanted here, leg off. " It was difficult to see exactly what had happened it was so dark. The men daren't use torches, the light would be seen from the air and make a perfect target for enemy bombers.

The injured were carried on stretchers and into the

ambulance. The lady wearing the tourniquet was still shouting about her missing leg. Her husband tried to soothe her. Then he whispered to my dad, "Did you find her leg?" "They're looking for it mate, " Dad answered, knowing there was no chance of finding it. Just as the driver started the engine, the lady's husband said, "It was propped up against the shelter just inside the door."

"What was?" Dad asked.

"Her wooden leg," he replied.

In the factory where I worked, there were humorous notices stuck around the walls to keep up our morale. One read: 'You don't have to be mad to work here, but it helps.' And,

'If an incendiary bomb falls through the roof, do not lose your head, put it in a bucket and throw sand on it.' This was meant to be serious. There were other notices, not so polite.

The night that's etched on my memory for all time, was in nineteen forty one, the day after boxing day. It was a dreadful night. The bombing was particularly horrendous. South East London and the surrounding districts were continually being blown up and so many fires that some people described it as the second great fire of London. Dad was on duty at the time, not only heavy bombs were dropping but incendiaries as well and as we had to put them out, we couldn't go into the shelter; as fast as they were extinguished, more flared up. After sometime when things had died down a bit, we were exhausted, so we went indoors to make some tea. Suddenly, Judy, our dog, barked at us and crawled underneath the kitchen table.

"Why is she doing that?" I asked.

It must have been a few seconds later we knew why. We didn't hear the bomb, it was too near. The first thing I knew, was coming round after being knocked out. I felt sticky all over and slowly realised it was blood which seemed to be everywhere and I was spitting out debris and trying to remove glass from my face and clothes. This was difficult to do when you can't see what you're doing in the dark with debris and bombs still dropping around.

I mumbled in the darkness, "I've been injured."

Mum answered, her voice barely above a whisper as she was still dazed, "So have |."

We waited for Connie to reply. But she didn't. Then Mum's voice again, "Con, Con, you alright?"

No answer. We feared the worst. We waited and waited. Then at last we heard my sister's muffled voice, "My head feels as if it's been cut, but I'm O K"

'Thank God," Mum said.

Mum wasn't sure where she'd been injured, but everywhere was hurting.

Even though I was twenty one years old, I was a bit childish

at that moment.

"What about the doggy, she warned us about this?"

Then we heard a little bark as much as to say, "I'm still alive."

"Arrrhs!" were heard.

We had to wipe the dust from our eyes before we could open them. We were all covered in glass, which was responsible for most of our injuries. We groped around trying to find our bearings in pitch dark and talking to each other all the time, mostly about our dear Dad and praying that he was alive. We weren't in the dark for long. There was a whoosh! and flames shot up in front of us, revealing a deep crater where the front of the house had been. We grabbed tight of each other as we stumbled through the rubble. There was another whoosh! Flames surrounded us. We heard afterwards that the gas main had been hit.

Judy stayed close to us as we picked our way over the rubble to find a way out. It was a miracle she was unscathed, because the table she had sheltered under wasn't there any more.

"Come on," Mum said, "We'll try and find a way into the back garden." How we managed that is still a mystery, because there was another crater where the back of the house had been.

But eventually we managed to find the garden and were relieved to find the dug out still intact and stayed there what seemed hours as the bombing continued. We took some comfort from the sound of the Ack Ack guns fighting back, on Blackheath and in Greenwich.

"Perhaps someone will soon come and rescue us," Mum said hopefully.

"I wonder what's happened to Dad," we kept saying.

Then at last, we heard a voice call out, "Are you in there?" It was our wonderful Dad. It was a dreadful shock to him when he came home and found his home in ruins and wondered if we were still in the land of the living. As Dad began to make his way among the rubble the warden in charge tried to stop him. "There's no one left in there he shouted, "You can't go in it's too dangerous.

"You can't tell me what to do, my family is in there somewhere. You can't stop me 'I'm Light Rescue," Dad shouted back, pulling rank.

I can't describe the look of relief on all our faces when we found our family was still in one piece, (well almost) And we kept thanking God.

As Dad was helping us out of the shelter, Mum said to Dad, "Your dinner's in the oven, it's your favourite, boiled bacon." She must have been joking.

"Oven!" Dad cried, "There's no 'bleepy' oven there."

Trust Dad to give a funny answer as well. That's what our family were like, no matter how bad the situation we'd see the funny side. It's the worst situation we have ever been in. We all laughed hilariously. It was really hysteria, but it was better than crying and feeling sorry for ourselves. The tears came next day, when we found we had no home left.

Dad was our rock of Gibraltar, not only did we love him to bits, we felt safer when he was with us.

Anyway, Dad attended to our wounds as best he could and took us to the nearby first aid station. Then a make-shift ambulance, a grocery van, took us to the hospital (a school in Greenwich). After we' d been attended to, we spent the night trying to sleep. Connie and I were given a children's wooden form to lie on. We didn't get any sleep. It was too uncomfortable. My left arm was in a sling and the other side of my body, my bottom had been jabbed with a needle,

with something to keep me quiet because I couldn't stop talking.

Mum laid on the table usually used for another purpose,

I won't mention what. Then when the 'ALL CLEAR' sounded Dad and our little dog walked all the way from Lewisham to Charlton where his sister lived. Next day, we managed to salvage one or two bits from the pile of rubble that had once been our home. We found the left-over piece of pork from our Boxing Day dinner and the rest of the Christmas cake Mum had baked and iced, she'd saved up the rations for months for this.

Dad went to Greenwich Town Hall to beg some clothing coupons, telling the man in charge that we only had what we stood up in.

Then a cousin took us in his van to the auntie at Charlton and she took us in until we found somewhere else to live. It was the day of my uncle's, her husband's funeral. He was a Signal man at Victoria Station and had been killed in an air raid while on duty, so we all comforted each other. At auntie's house we washed the pork under the tap and dusted off the cake and ate them.

There were many casualties that night in South East London, A lot of fatalities including our neighbours.

This following memory is a 'favourite' of mine. Amongst the ruins of our house was a thin column of bricks that had once been part of my bedroom wall.

It reached up into the sky and there was still a scrap of wallpaper stuck to it; clinging bravely to this, was a small picture of Jesus surrounded by children of all colours and nationalities. This was given to me in 1934 when I left school at the age of fourteen. I have taken it with me every time I moved home. It's always hung on my bedroom wall above my head.

Copyright Thurza Blurton. Mrs Thurza Blurton

5 Mosyer Drive

ORPINGTON

Kent BR5 4PN 01689 873717

Contributed originally by Doddridge (BBC WW2 People's War)

The contributor has agreed to the BBC terms for entry of stories to the website.

This is the second part of my story, the first part covered my childhood and the early part of the war.

The village of Heilly was on a very minor road and we could hear the sound of bombing and gunfire before we met up with the main road, on approaching the main cross road we could see that it was full of refugees and Dad decided to drive across fields and then find a way across in the

direction we required, we could from these fields also see civilians walking in front of tanks in adjoining fields and German planes bombing and machine gunning the stream of refugees which included French soldiers and army lorries and ambulances. We finally found a way across and entered a small village which had been shelled and bombed, the road was badly damaged and difficult to negotiate and we were therefore moving very slowly, at one point there was a ladder against a wall and at the top of this ladder was the body of a man with all his inner parts hanging down to ground level, this was a sight which I will never ever forget and does on occasion flash before my eyes even now 63 years later.

It soon became obvious that we would not be able to reach the coast and

it was decided to try and head south towards Rouen, this involved joining the stream of refugees some of whom moved aside to allow cars past but this also involved being straffed by enemy planes forcing us to leave our cars and seek shelter in ditches or behind trees.

The sight of remains from the straffing and bombing will remain with me for ever and it is a fact that even now I cannot watch a film in which this sort of horror is shown.

A couple of times we managed to get ahead of the refugees gaining a fair distance only to be overtaken at night when we had to rest with the cars

hidden from sight behind branches, in fact on the first night we were overtaken by the Germans and one of their vehicles stopped only a few yards from us for a call of nature.

By the next morning there was no sign of the Germans and we once again joined the stream of refugees getting ahead of them again for a short distance only to meet up with another endless steam, it was on this occasion that a heavy bombardment and straffing began and my parents

and my younger brother and 1 took shelter in a deep ditch with water running in the bottom, there was a anti aircraft battery in the adjoining field and the fumes and stench of cordite from the shells and bombs started to make us choke, my Mother tore strips off her underskirt and wetted these in the water and we had these over our faces until action had stopped as the cordite fumes was also making our eyes very sore.

We then carried on again until we had almost reached a road leading through a wood when enemy planes once again started very heavy

straffing, we just managed to get inside this wood and my Mother took me for shelter behind a tree and Dad did the same with my brother, this time 1 did a very stupid and dangerous thing by leaning my head out of the shelter area at which time the pilot had reached the end of his straff run and was about to lift up above the trees ,1 could clearly see this pilot prior to the aircraft going up, 1 got a well deserved telling off from my parents for exposing myself to so much danger.

We then carried on but the clutch on the other car gave out and Dad towed this car until we found a cafe where he dismantled the clutch and repaired the cork driven clutch part with corks cut to size by hand from a supply of corks from the cafe. He was of course a motor mechanic. This was his first rescue as a mechanic during our escape. 1 did forget to mention that we had until this time kept our dog (Bella) with us and the cafe owner kindly offered her a good home.

Following all this we carried on in the stream of refugees until we ran

out of petrol and had to carry on on foot with our cases etc in the handcart, we still had to endure the machine gunning and bombing and the sight of countless bodies.

We eventually arrived at the port of Rouen on the river Seine as French

troops were preparing to blow up the bridge in an attempt to try and stop the Germans, [this bridge for some reason did not get blown up. These soldiers were also trying to restrict the flow of refugees crossing the bridge without success and having managed to cross over we turned right along the quayside whilst the majority of refugees carried on down the main road heading south.

We could see that some distance along the quay were some merchant ships and beyond these 2 liners, we therefore first went to where these

liners were and it could be seen that they were absolutely full of refugees,

the foot ramps were still in position with a senior crew member at the quayside to stop further loading and despite my father pleading to at least

allow my brother and I aboard the requests were refused. We therefore turned back and my father then asked the captain of a Norwegian coal boat for help. The captain refused the request stating that as much as he would like to help, the risks for our lives through a sea with minefields were far too great. This request for help had been overheard by a member of the ships crew.

We therefore left the area of the Norwegian boat called (the Ringhom) from Bergen, and were wondering what to do when my father was approached by a sailor who said that he was a member of the crew of this boat. He had discussed our plight with other members of the crew who without delay told him that they would without authority help us to go on board.

We were told that the boat would be leaving for England in the early hours of the next day and told us to come back after dark at which time the captains attention would be diverted while we were smuggled aboard.

Everything went according to their plan and we were taken down to the

bilges where we were to remain until the ship sailed.

During the night we heard the noise of heavy boots and it would appear

that these were the boots of German soldiers who despite the boat being

from a neutral country had insisted on carrying out a brief search before

giving the captain plans of the minefields for the sea crossing to England,

The Germans could not due to neutrality refuse sailing and had to issue these plans.

The boat left the docks in the early hours and a crew member then took us

on deck to the captain who did not appear to be surprised, he told us that

he certainly could not put us off and that his quarters and other quarters

would be made available for us.

I must now come to an extremely sad part.

You will recall that I told you about the 2 liners that we could not get on.

On reaching the estuary of the River Seine we encountered the scene of a

terrible tragedy, both of these liners had struck mines and sunk. The prows of both ships were sticking up out of the water and as we sailed between these prows numerous bodies could be seen floating on the surface.

We were later told that the boats were British, therefore considered as

enemy by the occupying forces and they were not provided with mine

field charts or given clearance to sail. We were also told that there were

no survivors. How fortunate for us that we were not allowed on board either of these ships.

And so started our sailing to England little realizing the distance or time

which would be involved, indeed only one person knew our final

destination and this was of course the captain.

We had been at sea for 2 days when the power machinery for the boat which was steam powered broke down, a major fault having developed

for which the necessary spare part was not available among the normal

spare parts kit, this necessitated the manufacture of the required part

and the engineer and my father were working for a full 36 hours making

this part out of any suitable material that they could find, with the failure

of power the anchor could not be released and the ship was therefore

drifting for all of this time in mine infested waters. I of course being so young did not realize the considerable danger we were in and kept looking at the sky at the slightest sound of aircraft as I had now associated these with the previous horrors on land and I was in constant fear.

After many more days at sea we eventually arrived at Barry docks in South

Wales having avoided with the use of the minefield map, the minefields in the English channel, the sea area around Lands End and the Bristol

channel.

The other British family were, up to this time with us though we saw very little of them even on this small boat. I really do not know why they kept apart from us, I do know for certain that my Father had to make all the decisions and that our car was in the lead right up to the time that we had to abandon the vehicles.

On arrival at Barry docks we were taken to a building and it was from the

moment that we entered this building that we lost all contact with them.

This was indeed very strange.

From this building we were taken a short distance along the coast to another place which I would now describe as an old workhouse, it seemed

so strange on the way to see families enjoying themselves on the beach

with what appeared having not a care in the world while so much was going on in Northern France. Indeed our troops had while we were at sea

endured hell on the beaches of France, and we of course through lack of

radio contact knew nothing of this. On arrival at this other building we were met by ladies who I now assume were members of a voluntary organization. Mother and Harold were taken to one part of the building while dad and I were taken to another part where we had to take off our cloths and were then dusted with a powder, this was followed by a bath and we were then given clean clothes. We were then reunited with my mother and Harold and given a meal.

The night was spent in this building and the following day we were

allowed to leave and made our way to Catford in London where we

stayed while dad went to Exeter to arrange to stay with Corky Newcombs

wife and young son. After a couple of days we went to Exeter where we stayed for 4 or 5 weeks while dad went on to Faringdon where his sister lived to find a house and employment.

Dad found a small terraced house which he named [Heilly] and also found employment as a motor mechanic and also as a special war reserve police constable. He was working all sorts of very long hours in order to provide as much as possible to make the home comfortable and we therefore did not spend a great deal of time with him as a family. I was then just 13 years old and my prior education had all been in France, I could read a little English, I had no knowledge whatsoever of pounds, shillings and pence or measurements of weight, liquids or distances, in plain language I knew very little and could not write in English as I could not spell.

You may now guess that I had to put up with a considerable amount of

teasing by other children and was often involved in fights, I did however

have one very good friend who would always come to my aid resulting in

other kids coming off worst, unfortunately this occasionally had bad

endings, the abusers would go home with black eyes or bruises and tell

their parents that I had picked on them, the parents would then come to

the school and complain saying I was a trouble maker and should not be

in this school and should go back to France.

As you can see, life was a little hard for the first few months.

School in those days due to the number of evacuees was restricted to half

a day for locals and half a day for evacuees.

I left school at the age of 14 and therefore had a total of approximately

6 months of English education but I am pleased to say that due to homework and hard study I was equal to others of my own age. Between

the ages of 13 and 14 I supplemented my pocket money by first being a

lather boy in a barber shop. This involved putting shaving soap on the men’s faces with the aid of a stick of soap, warm water and a shaving brush, the barber would then come along with a cut throat razor and

shave the mans face, this job was quite good and I used to get quite a few

tips. However the school inspector found out and I had to stop because I

was under age for an indoor job. I then went as a telegram boy on

Saturdays.

When I left school I became employed as an apprentice motor mechanic

for a period of 5 years, my starting pay was 5 shillings per 48 hour week, equal to the sum of 25 pence per week in the current decimal coinage. there were 2 mechanics in this garage and one of these was shortly after my start transferred by the government to war work in Oxford. I was very interested in this work and as the garage also included a taxi, I did at the age of 17 qualify to carry out numerous journeys as a taxi driver as special licences were not required in those days, you simply applied for a driving licence at the age of 17 no tests being applicable.

When I was 14 I joined the Air Training Corps with my brother Albert, we

had 2 R A F training airfields near Faringdon and on most Sundays we

used to put on our A T C uniforms and go to one or the other of these

airfields and ask if there was any chance of a flip, our requests were

always granted providing there was available space in a plane, these

being Airspeed Oxfords or Tiger Moths.

At the age of 15 I did, with my employers permission, join the local fire

service as a messenger, this involving sleeping at the fire station on

alternate nights and also rushing from work to the fire station when the

alarm sounded, at the age of 17 I became a fireman being paid a retainer

fee and having an alarm bell in my bedroom.

Most young men were called up to join the services at the age of 18 but

apprentices were exempt until they had completed the term of their

apprenticeship, I on completion of my apprenticeship would however have been exempt from call up as motor mechanics were mainly sent to a local military establishment as civilian employees.

I wanted to go in the army and as my apprentice completion date approached I went to Bristol in May 1946 and volunteered, my employers

did not know this as they would surely have tried to stop me and when a

letter arrived informing me to report to Ranby camp near Retford

Nottinghamshire my employers simply thought that I had been called up,

I can quite truthfully say that I soon regretted joining the army, our

instructing regiment was the Green Howards, marching in this regiment

is at the double pace and as one of the toughest regiments other training

was to say the very least extremely demanding.

If I could have found a way to get out I most certainly would have done

so, as it was heartbreaking.

However I survived and in January 1947 went out to the Middle East

serving in Palestine and Egypt until March 1950.

Now we come to the most important part.

When I came back to England I was granted 56 days leave and a few days

after returning to Faringdon I was with my old school friend George Smith

and we decided to go in to the local cafe called Jane’s Pantry for a cup of coffee, a Gorgeous waitress served us and I simply could not take my

eyes off her, I said to George that I would love to have a date with her

and he replied ask her, I had not really spoken to anyone I would be

interested in for over 3 years and I told him I was too shy, He laughed

and said ‘hey Binnie my mate would like a date’, Binnie replied ‘why cant

he ask hasn’t he got a tongue in his head?’ The result was that a date was

agreed this being one thing I have never regretted. We spent every possible minute together, after my leave was finished I was posted to Shepperds Bush in London and came home every weekend, my Mother was at that time spending a great deal of time in France with my Father who had returned with the war graves commission after the Normandy landings, and Binnie had, soon after we met, introduced me to her family, the thought of coming home to a empty house did not appeal and her parents very kindly put a bed in the parlour for me as this room was only used at Christmas. I though the world of her family. Binnie and I became engaged a short time before I left the army which was in July 1952.

I obtained employment as a motor mechanic and Binnie and I were

Married on the 28th of March 1953.

Our home was next door to my parents and life was not always easy,

there being the occasional in-law problem. We had three children while we

lived in Faringdon, Paul, Ruth and Donna.

Motor mechanics’ wages were very low in those days and I supplemented

my income with part time work as a barman, taxi driver and ambulance

driver. Promotion came along quite well in the motor trade and I eventually rose to the position of Service Manager, This was however a position from which there is or was no advancement and I decided to apply for a position as Auto consultant, Motor Insurance Claims Assessor with the largest Company in England. I got the job and we moved to a small village near Reading, I then changed Employers and we moved to Northampton where my second Son Lance was born.

I loved the work I was doing and was after a few years rewarded by

being appointed a Director of this Company. I stayed with this Company until retirement at the age of 65.

I always wondered what had happened to the gallant little Norwegian

boat and courageous crew.

My eldest son Paul who was apart time hypnotist did one day, ask us to

go to the television studios in London where he said he would be making

his first television appearance as a hypnotist, he said that he would feel

better doing this if he had family support. We went as requested and Paul appeared on stage, it was a CilIa Black show called Surprise, Surprise. I had never seen or heard of this show. Paul started well and then Cilla said to my great surprise it isn’t you we have to see is it Paul? it is your dad Cyril we want on here, I was absolutely astounded, Paul had informed the producers of the program in regards to our escape from France and my longing to know what had happened to the boat and crew and they in turn had after months of research managed to find 3 members of that crew and brought them to the television studio in order that I may thank them for all that they had done for us in 1940.

All the rest of the family knew what was happening and I was well and truly caught out. The sailors had told Cilla that they clearly remember my fear of enemy planes and how I was constantly looking at the sky. The 3 sailors had left that boat in late 1940 and it had been sunk by a German submarine off the coast of Ireland in 1941, all lives being lost.

This I think just about concludes my story up to the present time which is

May 2003 the year in which we have celebrated 50 years of very happy,

marriage .I must say that I have the most wonderful wife who encouraged me to write this account of my life and I most certainly would not have done so without her suggesting it in the first place.

God Bless You All.

C.M.C.