High Explosive Bomb at Ebury Strreet

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Ebury Strreet, Pimlico, City of Westminster, SW1W 8PF, London

Further details

56 18 NW - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by DOUGLAS ROTHERY (BBC WW2 People's War)

Chapter XI - A Proud Epitaph

Shelling had now become extremely intensive and have been warned to expect a counter attack. A tank to our front was a blazing inferno and was close to a stone built barn, two of my Section requested permission to go to the toilet and they ran to the stone barn, but no sooner had they disappeared inside, it was hit simultaneously by two shells and we couldn't see the barn for a cloud of dust. I was thinking well that's their lot, when out of the dust two figures emerged running like the clappers holding up their trousers, as you can imagine we roared with laughter especially when one them said, 'It was a sure cure for constipation'.

I am not exaggerating when I say that for every minute of the day and night the shelling and salvoes of rockets from the Moaning Minnies were terrifying, one continuous barrage, I have never known such a concentration before on such a comparatively small area. We could hear women and children screaming in terror in the houses to our rear many of which were ablaze, lighting up a moon-less sky. This barrage was still continuing in the morning with the same ferocity, no let up, it was most traumatic and horrifying witnessing this onslaught without any means of personal retaliation but just standing there awaiting the chance perhaps of a reciprocal respite when given the order to advance, these experiences cannot be expressed in words or films. Our exact map location at that very moment I hadn't the slightest idea mainly because Section leaders are not in possession of such, what I did know is that our presence was not at all entente cordial.

Regardless of this slaughter taking place around us, out comes Dad, God bless him, with our mess tins of precious sustenance, dumps it, then scurries back to where he has hidden our vehicle. No sooner had he done so, we sat down on the floor of the trench to partake of our meagre breakfast, leaving Gdsm: Bowse standing on guard and acting waiter. He was in the process of handing me my mess tin by reaching over two others when there was an almighty explosion. I was flung backwards by a terrific force and momentarily stunned. There was a few seconds silence ,then I called on the Mother of God for divine intervention and succour. I eventually could see out of one eye my hearing was naturally impaired, blood was pouring down my face, my arms felt stiff and numb, the front of my tunic was ripped away and both sleeves were in tatters. The poor unfortunate who was leaning over to me, Guardsman Bowse was killed, two others were injured no doubt his body protected us from more serious injuries. I was to learn some time later that a rocket shell had hit the perimeter of the trench so if it had happened a few seconds before we would have been all standing up. Someone put a bandage around my head and eyes and helped me and others into a vehicle which took us to the First aid post about a mile back. They cleaned me up a bit, re-bandaged my head and eyes, put both arms in slings then put me in an ambulance to be taken to the base hospital. No sooner had I laid down in the ambulance than I felt a joy of relief, everything seemed so peaceful, just the rumbling of shell fire in the distance as I gradually unwound from the tension and trauma of hell plus the fact I couldn't remember when I slept last, I was certainly going to make up for it as I went completely out.

Waking up as the cold air hit me, I was carried in on a stretcher into the Base hospital which was a very large marquee somewhere in France. After being put to bed a doctor along with a couple of others gave me a thorough examination and removed the slings from my arms. Apparently my chest arms and face were like a pepper pot caused, according to the doctor, by fragmented stones, these he said would eventually come to the surface and was nothing to worry about and were also in the muscles of my arms causing them to be stiff.

I remained in bed for about 3 weeks whilst they treated my ears and eyes and eventually allowed me to go to the washroom which was the first chance I had of seeing my face and it was a peculiar experience because I didn't recognise myself. Apart from it being peppered it was blown up like a balloon caused by the blast and my eyes were just slits, it was a bit of a shock. They seemed quite concerned about my eyes more so than my ears, which has left me with a steam train passing with its whistle blowing.

Whilst here I felt very proud when other patients on hearing that I was a Grenadier would come over to congratulate me on the achievements of the Guards Armoured Division. ( Div: sign:-- 'The Ever Open Eye'), a sign by looking at me, that must have seemed a contradiction.

This also gave me the opportunity to reflect on the trauma an infantry man uniquely experiences, yet at the end of his stint is not even given any more consideration to those who although not in earshot of enemy action are entitled to the same Campaign recognition which to me makes the medal significance less rewarding. (The powers that be I imagine would say 'You were only doing what was expected of you").. Shame.

After about six weeks I was informed that I along with others were to be flown back to Blighty, I was elated. One morning I along with about ten others, some on stretchers, found ourselves in the corner of a field where there was a lone Dakota, it wasn't long before we were up and away. Flying low over the channel to escape radar detection and on nearing the home coast we climbed, it was a wonderful feeling looking down on a peaceful countryside bathed in sunlight so much so I pointed this out to a fellow on a stretcher whom I expected to share my enthusiasm but he only gave me a scornful look. I then realised he was a Jerry.

We landed somewhere in West Bromwich because it was to a hospital there where I was to stay for a short while, thank goodness! It was very primitive. I was then transferred to a Birmingham hospital where I was eventually allowed out in regulation hospital blue and red tie thus giving me the opportunity to visit an Aunt. I was then transferred to Leamington Spa to the 'Home for the Incurables.' I hasten to add that service personnel were in a separate ward. Each evening a Victorian battle-axe of a matron would literally march through the ward with her entourage, who endeavoured to keep up with her, whilst the patients that were able, had to stand at the foot of their bed until she had passed through, you then had to go to bed. As there were no radio or headphones in the ward we naturally, being interested in the progress of the war sought permission to be allowed to hear the 9pm news in the Rest room, this was refused because it would upset the procedural practice carried on in the hospital for decades. It was decided that it was about time the rules were changed, so come 9pm we would sneak downstairs until one night we were reported. To cut a long story short I was appointed as spokesman and had to appear before the Head Administrator who threatened to report me to the army authorities, I likewise their draconian method of administration. We were granted permission to hear the 9pm news with a promise of headphones for each bed.

After a few months I was sent to Stoke-on-Trent convalescent army camp where after being issued with new clobber I was to meet up with many of my mates now patched up and eager to get back at the enemy. (If you believe that you will believe anything). I was very surprised to meet R.S.M Hufton who had certainly mellowed after his battle inoculation, I didn't know he had been wounded. He called me over and asked me what I was doing that afternoon. I nearly said 'I didn't know you cared'. Anyway he treated me to a football match between Stoke and Portsmouth and afterwards to a Cafe for a tea and a wad. 'There you are, they are human after all'.

After idling our time away here for a few weeks all Grenadiers were sent to Victoria barracks Windsor where I was to meet up with more patched up heroes straining on the leash, but before doing so there was much reminiscing over pints with old acquaintances, one of them being a Sergeant Twelftree who was a pall bearer at the funeral of HM King George V and was one of my buddies when we first went out to France so we had plenty to celebrate about. Unfortunately they were all to rejoin their units with the exception of Corporal Griffiths ex heavy and light heavy weight Brigade boxing champion who, like me was now downgraded to C2 and was to be my Corporal of the guard at the barracks one night. On reveille, Griffiths on dismounting the sentry, (who by the way was a recruit,) marched him into the guardroom and gave him the order to unload and in doing so the recruit inadvertently left a round up the breech and on pressing the trigger the bullet went into the ceiling scattering plaster all around the guardroom much to the amusement of Griff; who was curled up in muffled laughter behind him. The Picket officer a [Young Chicko] walked in immediately afterwards and I thought he had heard the report but apparently hadn't, which I imagined should have woken up all of Windsor, but he was just checking the Tattoo report as part of his duty by asking 'Everything all right Sergeant'. He didn't look anymore than 18yrs old and was at the same time walking around the guardroom tapping the plaster from side to side with his stick. When I explained what had happened he just said 'Oh, oh railly, oh, oh' and off he went. The recruit got off with a reprimand, I believe the shock it gave him was ample punishment.

Whilst here I received a Regimental Christmas and New Year card with the Divisional sign of the Guards Armour (the ever open eye) on the front cover, the card denoted the capture of Nijmegan among other battle honours and it was sent to me by L/Cpl Cox(Nobby) who was one of my Section before he got promoted. I was to learn later that he must have been killed whilst the card was in the post. 'God Bless'.

I was talking to a group of Americans who dressed in their army uniform were waiting at the main gate and had apparently arrived back from France the day before,and I asked them how much they enjoyed the luxurious accommodation of Victoria barracks, I am afraid their response wasn't at all complimentary. They said they were the Glen Miller band and were awaiting their leaders arrival. His disappearance to this day still remains a mystery.

Being downgraded, all that my duties comprised of here were Sergeant-In-Waiting and Sergeant of the barrack guard roles, so R.S.M. Snapper Robinson I should imagine decided that I might have some undiscovered talents which were not forthcoming here because he passed the Buck and me with it to 'Stobbs camp' near Hawick where I was to discover to my amazement, my mate of old standing Dennis Ward of No5 Section who told me that soon after my encounter he was shot receiving a bullet wound in the shoulder and was now pronounced fit enough to be shot at again and therefore was training with a contingent of Grenadiers for Far Eastern engagements.

I don't believe their gastronomic considerations were very high on their priority list because I was sent to H.Q Company to be in charge of their rations where each week I along with a driver in a 15cwt truck would have to proceed to Edinburgh to buy from the N.A.A.F.I. store, an amount determined by the manipulation of an allowance considered enough to sustain about fifty or so hungry warriors. One particular morning I was informed to report for Company Commanders Orders where I was expecting to be formally told that I had been recommended for promotion, unfortunately on meeting the Company Commander, he had just discovered at this late hour, that I was not A.1 and therefore was extremely sorry but it must be denied me. If the reason for not being upgraded was due to unsatisfactory ration distribution or whatever, I might have understood, but the lesson to be learnt is, when you go into battle, Its not only your life that is on the line but also your promotion so for goodness sake keep your head down. My ambition to join the Police when hostilities ceased was also shattered. Regardless of these adversities, I am proud to say my compensatory reward was having been in the company of wonderful comrades who also experienced the honour of being contributors to the historical glory of an equally glorious regiment

Whilst I was here peace was declared in May 1945 so my rationed superior recipients either seeking revenge or the alternatives to prunes and custard each Sunday lunch, decided to transfer my expertise to( Sefton Park) Slough where I was to remain until my demobilisation and in keeping with the usual Service administrative protocol, I was sent to the furthest point in the South of England, 'Penzance' Demobilisation Centre instead of the one close by namely Reading.

On arrival I was to be very disappointed with the few suits available and when I mentioned this they were very apologetic and came out with the old cliche, 'If sir would come back tomorrow when they were expecting a new consignment', Some hope! No homing instincts were to dominate my dress sense and I was to choose one I considered less conspicuous of the few remaining, a blue serge, which I am sure was made from a dyed army 'U' blanket in which I furtively crept away in, with the princely sum of 75 pounds for which I signed for. So after completing 8yrs with the colours because of the war, instead of the 4yrs in which I enlisted, I was to return home on the 2nd of March 1946 at the age of 26 years to the same establishment in which I left to join up.

That said, I reflect with sadness but with tremendous pride the heroic memories of those whose supreme sacrifice along with their past comrades, have contributed so generously and honourably to the proud epitaph of "THE BRITISH GRENADIERS".

2615652 EX L/SGT ROTHERY. D.. Arthur Baker survived the war after serving his time in the 3rd Batt:and we were never to meet up again until approx; 10yrs after joining the army together. He was married and lived in Guilford

Contributed originally by DOUGLAS ROTHERY (BBC WW2 People's War)

Chapter IV - Royal Encounters

In between the 24hr guard duties, other training continued, be it P.T. Weapon training, Education, First aid and of course Ordinary drill and Fatigues etc., every moment of the day was accounted for.

It wasn't many days after my Bank Guard that I noted with pride and panic, my name down on Daily Details for Buckingham Palace Guard. I was conversant with the procedural drill on arrival at the Palace, the changing, the double sentry drill on the pavement outside the railings of the palace whenever their Majesties were in residence etc., but wasn't so sure of the forming up on the square of my particular guard. I knew that I would have to 'Bloody Well Soon Find Out', so I discreetly watched the next Guard mount from a safe distance, (not allowed to stand and stare). But it didn't give me much confidence, because as soon as the order by the Sergeant Major was given,

'GET Ooooooon Parade'!

all that I could see was a mass of scarlet tunics and Bearskins criss- crossing in quick time trying to get to their respective Guards, St James Palace Guard being the senior followed by the Buckingham Palace Guard then the Waiting Guard, which parades in abeyance to replace those deemed as not suitably turned out by the inspecting officers. I rather despondently crept away not looking forward to my initiation and can only hope I don't have to learn by my mistakes.

On the day of my inauguration the Drummer blew the call to warn those who were for guard duty, finishing with a call called "TAPS the words of such known universally throughout the Brigade as "Youve Got A Face Like A Chickens Arse" thus reminding you that you have 20minutes before parade.

One of my chums gave me the once over before I gingerly make my way down the stone stairway trying not to crack the highly polished uppers of my boots, rifle in one hand, kit bag containing cleaning materials etc. suitably labelled for Buck House in the other for it to be taken their by transport. In all of this time, the band has been playing some known and some unknown airs, of which I am in no mood to appreciate. The officers of respective Guards, are patrolling up and down, also the Sergeant Major. Briefly all goes quiet, the next moment pandemonium when the Sergeant Major coming to a halt, bellowed out.

'GET Ooooooon Parade'!

This is it!

My heart misses a beat as I become part of this mass stampede in quick time, also trying to figure out where my guard marker is whilst at the same time trying to protect the precious hours of spit and polish on my size 11's from some other clumsy clots. These problems intermingled with orders being shouted from about half a dozen different W/Officers, I eventually make it.-Phew!- Now steady down.

After the formalities of the dressings, the roll call etc, comes the fixing of bayonets. The right marker marches forward the regulatory paces to give the signals for the fix, another panic sets in 'Thinks' Did I replace the bayonet into its scabbard after giving it its final polish! Its too late to check now. The next moment the order was given (FIX )- Yees"-"Thank Goodness," so far so good. Now for the inspection by the Guard Officer and"his entourage, Company Sergeant Major, Sergeant and Corporal, whatever fault one of them misses the other will pick up, whilst the band plays some lilting music which helps to drown the expletives being afforded to some unfortunate.

We march out to the usual tune on leaving barracks then to a stirring march to which we rightly and so proudly swagger along to, our hearts swelling with pride in the knowledge that we are the envy of the world. Somewhere along the route the guard W/Officer gave the command 'Escort to the colour' and being already briefed on what to do, I double out to the RH side of the road as part of that escort. whereupon on nearing Buckingham Palace we are recalled back into the ranks

.My first Stag [Guard Mount] was outside the front gates of the palace and I felt very proud and privileged yet at the same time extremely apprehensive after a warning from a experienced old sweat not to allow any of the public to stand by your side for photograph sessions as this could find its way not only for publication but also Regimental scrutiny looking for lack of poise or posture etc; also to be alert for the authoritive Regimental spy within passing taxi's, so with this in mind, no sooner had a damsel or anyone else posed themselves by my side for a photo, I would start patrolling [Spoil Sport].

On returning to barracks the next day someone called out that the official photographer was downstairs, so being still in guard uniform I took advantage of this opportunity which I believe cost me 2/6d (12&1/2p) including frame, which my parents were to proudly display.

Back to the varied training, where within a few days I had my first St James Palace Guard, which was fascinating , because the ceremony of the Changing of the Guard is in the courtyard within the palace overlooked by the balcony from which all historical proclamations are made. My patrolling on one of the sentry posts was under an archway, where, over the many years, the tip of the sentries bayonet had cut deep grooves into the stone roof. I bet that could tell a few stories!

My father being an ex soldier of the 4th Queens Own Hussars, gave me the following advice as I was leaving home to join up.

'Never volunteer for anything'.

But when volunteers were requested with the promise of a day off duty if we took part in an experimental inoculation, well, that was too good to miss! Three days later I was allowed out of bed! Never again, the shaking, aching and vomiting, we never found out what it was for but rumour had it that it was an anti malaria experiment. My advice is:

'Never volunteer for anything'.

Went out with the three musketeers, (whom I have already introduced), they

being older serving soldiers were in possession of civilian clothes passes. These could be applied for once you had served 12 months in the battalion, I still had 9months to go, this would then entail buying a suit (I am afraid that my 50/- (2 Pound 50p) one wouldn't pass the required standard on all counts). It must be smart and of a specified design and colour then inspected and approved by the Adjutant, anyway, I wasn't financially embellished at this short period of service to be able spread my limited retainer to cater for such extravagance. After wandering around Hyde Park and Speakers Corner, we decided to quench our thirst in a nearby Public house. The three six footers plus in their civilian clothes and wearing the traditional trilby hats (head gear must be worn), were the first to enter amid a buzz of verbal activity, which immediately ceased until I in uniform went over to join them. It was noticeable that, had there been any nefarious deals taking place, my presence must have assured them that we were not the 'BILL' but just the 'BILL BROWNS.'

I learnt it was common practice on returning to Barracks to bring back a fruit pie for the Guard Commander, this would be discreetly placed near the Tattoo report whilst being marked in, in the hope that this sweetener would be acceptable, especially if you were not quite within the second of the three essential conditions, namely (1) clean (2) sober and (3) properly dressed in uniform- alternately civilian clothes.

Professional jealousy would surface mostly between the Senior Warrant Officers of either Coldstream or Grenadiers regarding Regimental history, if the opportunity should arise. Such came the opportunity, when both battalions happened to be drilling at the same time on their respective halves of the square. R.S.M. Brittian of the Coldstream, (reputed at that time to have the loudest voice in the British army) bellowed out to his men (not as a compliment I may add) that they were drilling like a squad of Grenadiers. This was responded to with equal uncomplimentary fervour from R.S.M. Sheather of the Grenadiers. Apart from this light-hearted bantering, it never showed itself in any other way.

Other than our usual drill or musketry training, a few hours each week were spent on Stretcher Bearing (SB) courses, and the order of dress for this parade was Khaki Service dress and not Canvas Fatigue. On this particular occasion we were informed in the usual manner, i.e. Daily Details, that S.B's would parade at a certain time. After forming up on parade, the unfortunate Sergeant reprimanded us for not being in Canvas Fatigue. It was explained to him that Service dress was the usual uniform for Stretcher Bearers, whereas he had interpreted the S.B. as 'Spud Bashing' [ Potatoe Peeling] a well known term by all, especially the miscreants. (I might add that he wasn't allowed to live that down very easily among his fellow compatriots for quite some time)!

Guard duties were on average two per week, so I was now pretty conversant with the procedures, also the many different sentries orders for each of the various guard posts around the Palaces. One such order, among the many, at the front of Buckingham Palace was to keep prostitutes away from the railings, a task the Police on the gates, knowing the ones that come to ploy their trade, would soon sort out, also the onlookers obstructing your beat whereby a sharp tap on the ankles from a size 11 was the same interpretation in any language!

I was now entitled to a well earned rest, which was granted in the form of 10 days furlough where on arrival home after the customary greetings, the next question invariably would be, 'When do you go back'? This was the last thing you wish to be reminded of.

When it was time to return, I fortunately met another Grenadier Guardsman from my battalion at the railway station, who, although from a different Company we knew each other by sight. He spoke in an educated Oxford accent, smartly dressed in civilian clothes, bowler hat, brigade tie and carried a neatly rolled umbrella. On entering the carriage he rang the service bell and ordered a couple of whiskies which helped to dispel the gloom of departure. He then told me that he had already received 7 days C.B. for impersonating an officer. Apparently he, in his mode of dress, on returning one evening to Barracks was saluted by the sentry believing him to be an officer, and he in response acknowledged it by raising his hat (the normal response from an officer). This didn't go unnoticed by the Sergeant of the Guard, who didn't approve, neither did the Commanding officer. When we were nearing the barrack gate on return, he put the umbrella down his trouser leg and walked into the guardroom with a limp claiming that he had hurt himself whilst on leave, his explanation was accepted. Eventually he was to take up a commission in another Regiment and was subsequently killed in action. (Never volunteer etc. etc.)

Each Friday you could guarantee to having two boiled eggs for tea a ritual carried forward from my Depot days and no doubt from many years before. On this particular Friday, the eggs were unduly hard and black on being shelled, this therefore didn't satisfy most of the recipients who began to vent their anger by letting fly with eggs 'Properly Fired'. Before I had time to take cover the door suddenly opened and the Picquet officer plus escort marched in, thus restoring order. The men on being asked in the usual manner, ' Eeney Compleents'? several dared to respond. The Officer with the Master cook now in attendance seemed to agree there was reason to complain whereby no disciplinary action took place. Hereafter eggs were to be boiled on the day of consumption - only joking!. It was also the custom of having Prunes and Custard for Sunday's luncheon Sweet thus ensuring Regimental regularity!.

Now classed as an old soldier on double sentry duties, meant that I would be responsible for giving my sentry partner the regulatory signals for saluting and patrolling when called for on Palace guards etc. On one such occasion outside Buckingham Palace, at approx. 5am, therefore very light traffic and few pedestrians and no Police on the gates, along came a troop of 'Westminster Cowboys', these were Westminster refuse collectors, so called because they wore wide brimmed hats with the side brim turned up. They were no doubt reporting for work and as they drew level on their horse drawn carts, I signalled to my partner, with the regulatory three taps on the pavement with the butt of my rifle and we gave them the 'Present Arms', you should have seen their faces as they looked about in anticipation of seeing a member of the Royal family entering, you had to be very careful though, you never knew who might be watching.

Most complaints came from old retired officers who would walk past in civilian clothes for the sole purpose of getting a salute, so any civilian wearing a dark suit, bowler hat and carrying a neatly rolled umbrella, you took no chances and would salute giving them the benefit of the doubt. On another occasion a Troop of Household Cavalry were passing by on their way to Horse Guards Parade and I naturally Presented arms, they in response gave the customary eyes right and sounded the Royal salute on the trumpet, I was waiting for the officer to give the eyes front, he in turn was waiting for me to come down from the Present, eventually, as they got further and further away, I thought I had better do something, even if it meant waving goodbye, so I came down from the Present and he then gave eyes front, plus no doubt a few other chosen words, he being in the right. I was expecting to hear a complaint about this on returning to the Guardroom but it was not reported, misdemeanours committed on public duties warranted double punishment.

Later in the week one of my postings was at the rear of the Palace and before doing so the W/O of the guard, stated, 'He didn't want reports of 18ft guardsmen patrolling along by the perimeter wall'. Apparently this phenomenon was reported by a civilian in the street outside about a previous guard, where it was surmised a Guardsman had placed his Bearskin onto his bayonet on the end of his rifle and paraded it along the top of the wall.

For posterity I had better relate a rather amusing incident of Royal character whilst I was on that sentry. My post was near the stone steps leading down to the lawn. I heard children laughing and chasing each other, whence one of them a young girl of about 7 or 8yrs of age ran down the steps onto the gravel path of my beat. On recognising her to be Princess Margaret I Presented arms, she ran back up the steps to her sister giggling, no doubt bemused by the reception, repeated the performance.

whereupon I again Presented arms. I assumed she was about to do it again when I heard a male voice, whom I imagined was a member of the staff , usher them inside.

I heard of a not so Royal incident which occurred on Buck; Guard by a Guardsman Cosbab from our No2 Coy. Apparently during a very humid night, he had left his post and was discovered by the night patrol cooling off his feet in the water of the Victoria Memorial opposite, knowing him and his previous antics, I quite believe it. Although very likeable he was a proper Jekyll & Hyde character with a unpredictable devil may care attitude.

The lining of the street was part of our itinerary, which took place for the reception of His Majesty the King of the Belgians, Prince Michael of Romania, the openings of Parliament etc. etc. On one of these occasions because of the inclement weather, order was given to don capes. It was then revealed how the old sweats managed to square up their capes so precisely, when parts of cigarette packets etc. fluttered suspiciously to the ground. Another wheeze I was to learn was that the back tunic buttons were a tourist souvenir attraction, so it was wise not only to sew them on, but to thread a tape through the back of the buttons to help prevent this activity.

Contributed originally by Stephen Bourne (BBC WW2 People's War)

My Aunt Esther was a black working-class Londoner, born before World War 1. Her life spanned almost the entire century (1912 to 1994).

Her father, Joseph Bruce, settled in Fulham, west London, during the Edwardian era when very few black people lived in Britain. He came here from British Guiana (now Guyana) a colony in South America. He was a proud, independent man.

Aunt Esther left school at 14 to work as a seamstress and in the 1930s she made dresses for the popular black American singer Elisabeth Welch. After Joseph was killed during an air raid in 1941, Aunt Esther was 'adopted' by my (white) great-grandmother, Granny Johnson, a mother figure in their community.

Esther said, 'She was like a mother to me. She was an angel.' For the next 11 years Aunt Esther shared her life with Granny (who died in 1952) and became part of our family.

During World War 2, Aunt Esther worked as a cleaner and fire watcher in Brompton Hospital. She helped unite her community during the Blitz and having relatives in Guyana proved useful when food was rationed.

She said, 'Times were hard during the war. Food was rationed. Things were so bad they started selling whale meat, but I wouldn't eat it. I didn't like the look of it. We made a joke about it, singing Vera Lynn's song We'll Meet Again with new words, "Whale meat again!" Often Granny said, "We could do with this. We could do with that." So I wrote to my dad's brother in Guyana. I asked him to send us some food. Two weeks later a great big box arrived, full of food! So I wrote more lists and sent them to my uncle. We welcomed those food parcels.'

In 1944 the Germans sent doodlebugs over. Said Aunt Esther, 'When the engine stopped I wondered where it was going to drop. It was really frightening because they killed thousands of people. A doodlebug flattened some of the houses in our street. Luckily our house was alright, even though we lived at number thirteen!'

In the late 1980s I began interviewing Aunt Esther and in the course of many interviews I uncovered a fascinating life history spanning eight decades. Aunt Esther gave me first-hand accounts of what life was like for a black Londoner throughout the 20th century. A friendly, outgoing woman, my aunt integrated easily into the multicultural society of post-war Britain. In 1991 we published her autobiography, Aunt Esther's Story, and this gave her a sense of achievement and pride towards the end of her life. She died in 1994 and, following her cremation, my mother and I scattered her ashes on her parents' unmarked grave in Fulham Palace Road cemetery. Granny Johnson rests nearby.

Contributed originally by ageconcernbradford (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People`s War site by Alan Magson of Age Concern Bradford and District on behalf of Malcolm Waters and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site`s terms and conditions.

The war against Germany was declared in 1939.

My parents had already separated, fortunate for me I stayed with my Father and my Sister Nora went with Mum.

Nora was really my half sister 6 years my senior yet I never looked on her other than my whole sister.

Nora’s name was Robinson, my Mother’s maiden name. Nora eventually left home to join a circus.

Dad, an ex regular soldier, who served with the Northumberland Fusiliers in the first world war, there was very little he could not put his hands to. He baked all our bread, a brilliant gardener, was a very good cook and kept our home spic and span.

Sadly he rarely talked about his life so I really never found out much about him. I know he was a Geordie and had a brother Billy, but what part of Newcastle I have no idea.

End of January 1940 was a very bad winter. Dad jumped off the running board of a bus, slipped and struck his head on the kerb. He had a stroke and died on the 10th February in St Johns Hospital, Keighley.

Going down Airwarth Street my Uncle Joe told me my Dad was dead. His last words were the start of my Christian name MAL then he passed on. I must emphasise the point my Dad was a brick, he lived for me. I did cry at night when I was alone, realising I would never see or hear his face or voice again.

My life changed so much that at times I lived with my schoolmate Ken Smith, we both worked in Edmondson`s Mill, Keighley as doffers. The foreman threw a bobbin at me as I was sat on a bobbin box and I threw as many back at him and got the sack.` I left to work in a steel works shovelling steel into a foundry, then I did some lumber jacking at Oakworth, Keighley. I ended up at Doublestones Farm in service above Silsden for the Fothergills. I spent six months from 5am until 11pm at night building walls, shearing sheep, dipping sheep, harnessing the horse, burying dead sheep, milking the cows, feeding and mucking out.

Keighley was normal, one hardly knew a war was on, working on a farm was even more remote. After six months farming, I asked Fothergill, can I go to Keighley Fair on Saturday afternoon. He said, “what am I going to do without you”. So I went to the fair and never returned to farming.

Mum and I went to London after the Blitz, even then night and day bombing was daily. You could hear the distinctive drone of Jerry as they gradually got nearer and the bombs got nearer. When we arrived in Fulham we had no money, looking for a Mrs Quinn who had left her flat leaving no forwarding address so Mum and I went knocking on doors until a Mrs Lampkin put us up. Mum was probably desperate having no money and no job. I must have been a burden to her.

I went to school at Ackmar Road with some of Mrs Lampkin’s boys. I adapted to life quickly and made the best of it. Mum then decided London was too dangerous, so she sent me to Ponterdawee South Wales as an evacuee. I well remember saying good bye to Mum stood on Paddington Station with my overcoat on, a label with my name and destination, my gas mask, identity card, ration books and teachers who were taking care of us. We arrived at night time in a schoolroom in Ponterdawee where our names were called out, a person stepped forward and took my hand a man and his son were my carers. I cannot remember their names, but his son was about my age so he taught me the ways of the Welsh. I quickly adapted getting free coal from the slag heaps. Taking the cows to the bull and getting diced cheese with brown sauce. I enjoyed my stay in Wales. I was treated very well.

Mum had established herself in Fulham she had a flat, then Nora came back into our lives again. She had blossomed into a bonny young woman who looked after me. At Ackmar Road schoolboys used to play pitch and toss, this was new to me as in Yorkshire gambling was not even on the cards. I can remember on Christmas going out singing carols to get Mum a Christmas card. She cried.

Nightly, the sirens went the whole sky was lit up with searchlights, I got fed up with getting out of bed. When Nora shouted of me to go down into the basement I said okay, you go on, I’ll follow you.

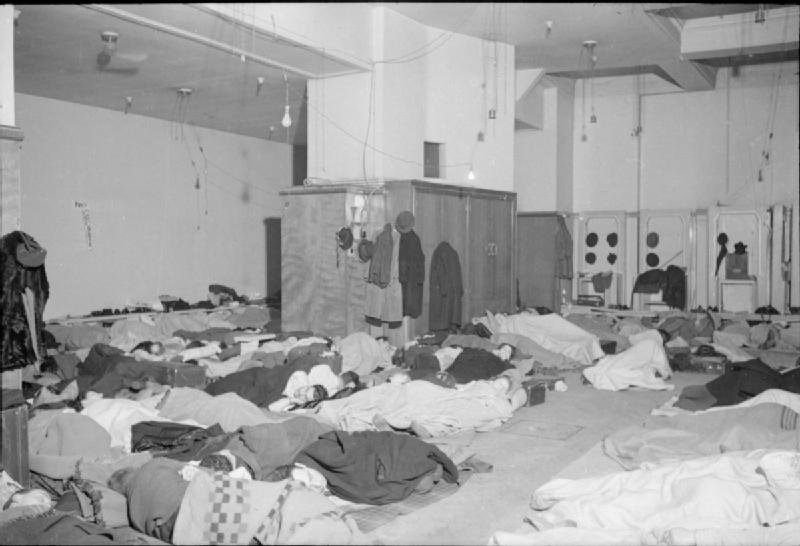

I could hear the bombers getting nearer and nearer, still lying in bed. Then I heard a whistling bomb that landed too close for comfort, my first reaction was to dive under the bed, my next reaction was to get down them stairs post haste. Nora was stood looking out of the back window, we were surrounded by buildings on fire. We were transfixed in awe at the blazing buildings, fire engine bells ringing, police cars whistles blowing, but we soon shot into the basement. Mum was on night work but the old lady always made us welcome. It got so bad at times we went to sleep on Piccadilly Station 75 feet below ground. Nora joined the ATS, I saw very little of her till later in life. One of the most frightening experiences was the mobile, ack ack guns that went off right outside our front door shaking all the windows. Most houses had stirrup pumps and buckets of sand just in case an incendiary came close.

Mum remarried a Peter Johnston from Tipperary In Ireland, he was an RSM in the Royal Engineers. He always respected me and was a real good family man, he always brought something home for me, but I am really a loyalist. I loved my own Father so much I could not accept another Dad, sad in a way, because he was a father of eight children who went in the Children’s Home in Keighley. They were all good children who’s mother fell down the stairs and broke her neck. Mum and I went to live in Townhead Glasgow to be near Peter who was stationed in Inverary. I went to school in Townhead I joined the Boys Brigade and was also a Lather Boy in a Barbers Shop. We got a bus from Robertson Street to Inverary went up the Rest and be thankful to arrive to see some real military movement. Assault craft, vehicles running backwards and forwards obviously getting ready to go to Dieppe. I slept in a huge bell tent while Mum and Peter went off to a Hotel. Peter was a very musical man he ran the Isle of Capri Band up Woodhouse, Keighley, an accordion and kazoo band who were very very good, they won many cups and shields, parading them around the Wood house Estate (pre War)

Back in London again in OngarRoad, Mum had a flat. Peter committed bigamy so Mum was on her own again. I remember going back to Keighley to spend my last days at Holycroft Board School, then back to London again. I got a job with the Civil Defence at Chelsea Town Hall and joined the London Irish Rifles Cadet Corps at Chelsea Barracks as a cadet soldier. As a messenger boy in the Civil Defence I cycled round the streets in uniform and my steel helmet on to various people of notoriety including the Chelsea Pensioners. Mum got a job in Peterborough looking after a man and his son, again his son was around my age, he was a brilliant young artist. He drew Peterborough Cathedral very professional. One day I went to Yewsley right next to the American Fortress Base. Looking up in the sky I could see and recognise a Jerry plane diving straight toward the street I was in. I ran like hell resting behind an Oak tree in a church yard watching the plane strafing the main street with cannon shelling, a close call.

I also worked in Dubiliers factory at Acton, making gallon petrol cans and we listened to " Music While you Work ". I also in Grosvenor House,Park Lane as a paticia`s assistant and the Americans occupied the hotel in the war years.

While in the Civil Defence I saw vapour trails of V2 rockets that landed somewhere toward Westminster. I went to Romford one night to stay at Harry`s, my mate`s house, as usual the sirens went moaning Minnie. It was like watching a film show looking over London with the bombers dropping canisters full of incendiaries. I commented to Harry, someone is getting a pasting, I found out Fulham had been hit again, a friend of Mum’s showed me his burnt shoes caused by kicking an incendiary out of the house. Everywhere was devastation, doors burned, windows blown. One chap, playing the piano had an incendiary pass through the roof straight between him and the piano into the next floor. I went to Putney one day, as normal, sirens sounded, my bus stopped on Putney Bridge, coming up the Thames was a V1, a buzz bomb, I watched it from the top deck coming right above the bus. The engine stopped. I watched it glide into a block of flats at Barns Bridge. I had the windows open, I felt the blast on my face from approximately half a mile away. One day I saw a squadron of 13 V1’s passing overhead in Gloucester Road, South Kensington.

The Army used to train on Harden Moor leaving unexploded bombs lying around. Two of my schoolmates playing with an unexploded PIAT bomb were blown to pieces in Lund Park, Keighley. Another friend Alec Joinson tried to saw through a grenade detonator, his face and arms were pitted with splinters he was covered in Sal volatile and was partially deaf.

I was very very lucky boy to be here to tell my story, I picked up a pop bottle that looked like bad eggs, fortunate for me I did not have a bottle opener so I through the bottle into a quarry. You should have seen the bright yellow phosphorous I’d picked up a Molotov cocktail, a phosphorous bomb.

Nora, my Sister, was in an air raid shelter that was hit and became flooded. She developed pneumonia then consumption. She spent many years in hospital and despite doctors warnings she had two children. At 43 neglected by her husband, she died and was cremated in Norwood Crematorium. She was a very very good mother who wasted away to a living skeleton. She spent many months in Brompton Hospital, I made all the funeral arrangements, the husband pleaded ignorance. I always enjoyed going to see her in London when I returned to Keighley later in life. I loved Nora very dearly and she never complained about all she suffered. Tommy Junior and Jenny still live in London, at Herne Hill. I occasionally call to see them.

The spirit of the Londoners in those dark days was second to none. We sang on the stations. I sang on Keighley Station when Ken Smith’s Father in Full Service marching order was off to Dieppe. Everyone sang “ wish me luck as you wave me goodbye” and “for a while we must part but remember me sweetheart “. Vera Lynne, Ann Shelton, Tommy Trinder, Arthur Askey, Flanagan and Allen and the Crazy Gang all made for good entertainment. Not forgetting George Formby and Grace Fields.

I am now 76 years old. Today I doubt the law would look on a single man like my Dad and the Gentleman in Wales as being capable of taking care of a family.

Contributed originally by BBC LONDON CSV ACTION DESK (BBC WW2 People's War)

"I'm a cockney born in Kingsbury Road near the Ball's Pond Road in the East End in 1937, so I was like 4, 5 and 6 when all this happened. I went to a Catholic School and during the Blitz when the air-raid sirens went, we'd get under the table and our teacher would say 'now you've got to pray' so we all prayed until the all-clear went.

One morning at 3, my mum's sister cam in and said 'there's a big bomb dropped near the old lady's house - that's what we called my gran - but she said she's all right. We rushed down the road and saw that a bomb had dropped on a school. I'll never forget, there wasn't a window left in none of the houses around. We went into a schoolhouse, the door was wide open, and there was blind man upstairs which they got our early; the whole ceiling had come down on him. We went into the kitchen and there was only about three bits of plaster left. The plaster round the rose on the ceiling was about the only bit left. I asked the blind man if he was okay and he said 'yeah' so I made him a cup of tea. We was lucky because if that bomb had dropped at three o'clock in the afternoon it would have killed all the kids.

I'll never forget this, the front door swung open and a fireman stood there. He said 'Everyone all right?' and one of the women said, well, I can't say what she said, but to the effect of 'that xxxxx Hitler can't kill me!'

We lived off the Ridley Road at the time and during one of the air raids one night, everyone went down the shelters and my dad said to me "Want to watch the airplanes?' My mum said 'That's not a good idea', anyway, he put me on his shoulders and we stood in the doorway and watched the dog-fights overhead. And I tell you, when them German planes got caught in the headlights, they had a hell of a job to get out. Anyway, the morning after these raids, all us kids'd go out collecting shrapnel from the shells, I had a great big box of the stuff.

Was I scared? Only when I was in bed at night and the air-raid warning went. When you're asleep and you suddenly woke, you didn’t' know what was happening so it was pretty frightening. At that age, you didn't know what air raids were all about. Some of the time I slept in the cupboard under the stairs and it felt a bit safer there.

One day, I went round to the corner to my aunt's house and she was sitting by the window when there was an air-raid warning. Inside the window where she was sitting was a table with a statue on it. They told her to come in away from the window. I'll never forget this, there was a bomb blast, the window come in and the statue toppled off the table and onto the floor. If she hadn't have moved, she'd have been covered with flying glass.

My dad didn't go in the army, because he was wanted on the railways. He took me down the dog racing one day at Hackney Wick. This flying bomb - a doodle-bug it was - suddenly appeared over us. You could see every detail of it. We all ran. It went right across the track and dropped in a field somewhere.

One day a landmine dropped near us in Kingsbury Road and didn't go off. A fellow came down from the Bomb Disposal unit, to try to disconnect it and he got killed. Opposite us there was a block of flats and they named it after him - Ketteridge Court.

I was evacuated for a little time, to Kettering, but I don't remember much about it, only that I didn't like it. I'd have to ask my mum about it. She's 100 but still remembers everything.

Me and my family are Pearly Kings and Queens and we do a lot of charity work, entertaining with music and the old cockney songs and that (Phone 020 8556 5971). We are now the biggest 'Pearly' family, made up mostly of the Hitchins (my mum's family name) in Hoxton, Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Clapton, Shoredich, Hommerton, Dalston, City of London, Westminster, Victoria, Islington and Stoke Newington. "