High Explosive Bomb at Tite Street

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Tite Street, Chelsea, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, SW3 4NJ, London

Further details

56 18 NW - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by DOUGLAS ROTHERY (BBC WW2 People's War)

Chapter XI - A Proud Epitaph

Shelling had now become extremely intensive and have been warned to expect a counter attack. A tank to our front was a blazing inferno and was close to a stone built barn, two of my Section requested permission to go to the toilet and they ran to the stone barn, but no sooner had they disappeared inside, it was hit simultaneously by two shells and we couldn't see the barn for a cloud of dust. I was thinking well that's their lot, when out of the dust two figures emerged running like the clappers holding up their trousers, as you can imagine we roared with laughter especially when one them said, 'It was a sure cure for constipation'.

I am not exaggerating when I say that for every minute of the day and night the shelling and salvoes of rockets from the Moaning Minnies were terrifying, one continuous barrage, I have never known such a concentration before on such a comparatively small area. We could hear women and children screaming in terror in the houses to our rear many of which were ablaze, lighting up a moon-less sky. This barrage was still continuing in the morning with the same ferocity, no let up, it was most traumatic and horrifying witnessing this onslaught without any means of personal retaliation but just standing there awaiting the chance perhaps of a reciprocal respite when given the order to advance, these experiences cannot be expressed in words or films. Our exact map location at that very moment I hadn't the slightest idea mainly because Section leaders are not in possession of such, what I did know is that our presence was not at all entente cordial.

Regardless of this slaughter taking place around us, out comes Dad, God bless him, with our mess tins of precious sustenance, dumps it, then scurries back to where he has hidden our vehicle. No sooner had he done so, we sat down on the floor of the trench to partake of our meagre breakfast, leaving Gdsm: Bowse standing on guard and acting waiter. He was in the process of handing me my mess tin by reaching over two others when there was an almighty explosion. I was flung backwards by a terrific force and momentarily stunned. There was a few seconds silence ,then I called on the Mother of God for divine intervention and succour. I eventually could see out of one eye my hearing was naturally impaired, blood was pouring down my face, my arms felt stiff and numb, the front of my tunic was ripped away and both sleeves were in tatters. The poor unfortunate who was leaning over to me, Guardsman Bowse was killed, two others were injured no doubt his body protected us from more serious injuries. I was to learn some time later that a rocket shell had hit the perimeter of the trench so if it had happened a few seconds before we would have been all standing up. Someone put a bandage around my head and eyes and helped me and others into a vehicle which took us to the First aid post about a mile back. They cleaned me up a bit, re-bandaged my head and eyes, put both arms in slings then put me in an ambulance to be taken to the base hospital. No sooner had I laid down in the ambulance than I felt a joy of relief, everything seemed so peaceful, just the rumbling of shell fire in the distance as I gradually unwound from the tension and trauma of hell plus the fact I couldn't remember when I slept last, I was certainly going to make up for it as I went completely out.

Waking up as the cold air hit me, I was carried in on a stretcher into the Base hospital which was a very large marquee somewhere in France. After being put to bed a doctor along with a couple of others gave me a thorough examination and removed the slings from my arms. Apparently my chest arms and face were like a pepper pot caused, according to the doctor, by fragmented stones, these he said would eventually come to the surface and was nothing to worry about and were also in the muscles of my arms causing them to be stiff.

I remained in bed for about 3 weeks whilst they treated my ears and eyes and eventually allowed me to go to the washroom which was the first chance I had of seeing my face and it was a peculiar experience because I didn't recognise myself. Apart from it being peppered it was blown up like a balloon caused by the blast and my eyes were just slits, it was a bit of a shock. They seemed quite concerned about my eyes more so than my ears, which has left me with a steam train passing with its whistle blowing.

Whilst here I felt very proud when other patients on hearing that I was a Grenadier would come over to congratulate me on the achievements of the Guards Armoured Division. ( Div: sign:-- 'The Ever Open Eye'), a sign by looking at me, that must have seemed a contradiction.

This also gave me the opportunity to reflect on the trauma an infantry man uniquely experiences, yet at the end of his stint is not even given any more consideration to those who although not in earshot of enemy action are entitled to the same Campaign recognition which to me makes the medal significance less rewarding. (The powers that be I imagine would say 'You were only doing what was expected of you").. Shame.

After about six weeks I was informed that I along with others were to be flown back to Blighty, I was elated. One morning I along with about ten others, some on stretchers, found ourselves in the corner of a field where there was a lone Dakota, it wasn't long before we were up and away. Flying low over the channel to escape radar detection and on nearing the home coast we climbed, it was a wonderful feeling looking down on a peaceful countryside bathed in sunlight so much so I pointed this out to a fellow on a stretcher whom I expected to share my enthusiasm but he only gave me a scornful look. I then realised he was a Jerry.

We landed somewhere in West Bromwich because it was to a hospital there where I was to stay for a short while, thank goodness! It was very primitive. I was then transferred to a Birmingham hospital where I was eventually allowed out in regulation hospital blue and red tie thus giving me the opportunity to visit an Aunt. I was then transferred to Leamington Spa to the 'Home for the Incurables.' I hasten to add that service personnel were in a separate ward. Each evening a Victorian battle-axe of a matron would literally march through the ward with her entourage, who endeavoured to keep up with her, whilst the patients that were able, had to stand at the foot of their bed until she had passed through, you then had to go to bed. As there were no radio or headphones in the ward we naturally, being interested in the progress of the war sought permission to be allowed to hear the 9pm news in the Rest room, this was refused because it would upset the procedural practice carried on in the hospital for decades. It was decided that it was about time the rules were changed, so come 9pm we would sneak downstairs until one night we were reported. To cut a long story short I was appointed as spokesman and had to appear before the Head Administrator who threatened to report me to the army authorities, I likewise their draconian method of administration. We were granted permission to hear the 9pm news with a promise of headphones for each bed.

After a few months I was sent to Stoke-on-Trent convalescent army camp where after being issued with new clobber I was to meet up with many of my mates now patched up and eager to get back at the enemy. (If you believe that you will believe anything). I was very surprised to meet R.S.M Hufton who had certainly mellowed after his battle inoculation, I didn't know he had been wounded. He called me over and asked me what I was doing that afternoon. I nearly said 'I didn't know you cared'. Anyway he treated me to a football match between Stoke and Portsmouth and afterwards to a Cafe for a tea and a wad. 'There you are, they are human after all'.

After idling our time away here for a few weeks all Grenadiers were sent to Victoria barracks Windsor where I was to meet up with more patched up heroes straining on the leash, but before doing so there was much reminiscing over pints with old acquaintances, one of them being a Sergeant Twelftree who was a pall bearer at the funeral of HM King George V and was one of my buddies when we first went out to France so we had plenty to celebrate about. Unfortunately they were all to rejoin their units with the exception of Corporal Griffiths ex heavy and light heavy weight Brigade boxing champion who, like me was now downgraded to C2 and was to be my Corporal of the guard at the barracks one night. On reveille, Griffiths on dismounting the sentry, (who by the way was a recruit,) marched him into the guardroom and gave him the order to unload and in doing so the recruit inadvertently left a round up the breech and on pressing the trigger the bullet went into the ceiling scattering plaster all around the guardroom much to the amusement of Griff; who was curled up in muffled laughter behind him. The Picket officer a [Young Chicko] walked in immediately afterwards and I thought he had heard the report but apparently hadn't, which I imagined should have woken up all of Windsor, but he was just checking the Tattoo report as part of his duty by asking 'Everything all right Sergeant'. He didn't look anymore than 18yrs old and was at the same time walking around the guardroom tapping the plaster from side to side with his stick. When I explained what had happened he just said 'Oh, oh railly, oh, oh' and off he went. The recruit got off with a reprimand, I believe the shock it gave him was ample punishment.

Whilst here I received a Regimental Christmas and New Year card with the Divisional sign of the Guards Armour (the ever open eye) on the front cover, the card denoted the capture of Nijmegan among other battle honours and it was sent to me by L/Cpl Cox(Nobby) who was one of my Section before he got promoted. I was to learn later that he must have been killed whilst the card was in the post. 'God Bless'.

I was talking to a group of Americans who dressed in their army uniform were waiting at the main gate and had apparently arrived back from France the day before,and I asked them how much they enjoyed the luxurious accommodation of Victoria barracks, I am afraid their response wasn't at all complimentary. They said they were the Glen Miller band and were awaiting their leaders arrival. His disappearance to this day still remains a mystery.

Being downgraded, all that my duties comprised of here were Sergeant-In-Waiting and Sergeant of the barrack guard roles, so R.S.M. Snapper Robinson I should imagine decided that I might have some undiscovered talents which were not forthcoming here because he passed the Buck and me with it to 'Stobbs camp' near Hawick where I was to discover to my amazement, my mate of old standing Dennis Ward of No5 Section who told me that soon after my encounter he was shot receiving a bullet wound in the shoulder and was now pronounced fit enough to be shot at again and therefore was training with a contingent of Grenadiers for Far Eastern engagements.

I don't believe their gastronomic considerations were very high on their priority list because I was sent to H.Q Company to be in charge of their rations where each week I along with a driver in a 15cwt truck would have to proceed to Edinburgh to buy from the N.A.A.F.I. store, an amount determined by the manipulation of an allowance considered enough to sustain about fifty or so hungry warriors. One particular morning I was informed to report for Company Commanders Orders where I was expecting to be formally told that I had been recommended for promotion, unfortunately on meeting the Company Commander, he had just discovered at this late hour, that I was not A.1 and therefore was extremely sorry but it must be denied me. If the reason for not being upgraded was due to unsatisfactory ration distribution or whatever, I might have understood, but the lesson to be learnt is, when you go into battle, Its not only your life that is on the line but also your promotion so for goodness sake keep your head down. My ambition to join the Police when hostilities ceased was also shattered. Regardless of these adversities, I am proud to say my compensatory reward was having been in the company of wonderful comrades who also experienced the honour of being contributors to the historical glory of an equally glorious regiment

Whilst I was here peace was declared in May 1945 so my rationed superior recipients either seeking revenge or the alternatives to prunes and custard each Sunday lunch, decided to transfer my expertise to( Sefton Park) Slough where I was to remain until my demobilisation and in keeping with the usual Service administrative protocol, I was sent to the furthest point in the South of England, 'Penzance' Demobilisation Centre instead of the one close by namely Reading.

On arrival I was to be very disappointed with the few suits available and when I mentioned this they were very apologetic and came out with the old cliche, 'If sir would come back tomorrow when they were expecting a new consignment', Some hope! No homing instincts were to dominate my dress sense and I was to choose one I considered less conspicuous of the few remaining, a blue serge, which I am sure was made from a dyed army 'U' blanket in which I furtively crept away in, with the princely sum of 75 pounds for which I signed for. So after completing 8yrs with the colours because of the war, instead of the 4yrs in which I enlisted, I was to return home on the 2nd of March 1946 at the age of 26 years to the same establishment in which I left to join up.

That said, I reflect with sadness but with tremendous pride the heroic memories of those whose supreme sacrifice along with their past comrades, have contributed so generously and honourably to the proud epitaph of "THE BRITISH GRENADIERS".

2615652 EX L/SGT ROTHERY. D.. Arthur Baker survived the war after serving his time in the 3rd Batt:and we were never to meet up again until approx; 10yrs after joining the army together. He was married and lived in Guilford

Contributed originally by Stephen Bourne (BBC WW2 People's War)

My Aunt Esther was a black working-class Londoner, born before World War 1. Her life spanned almost the entire century (1912 to 1994).

Her father, Joseph Bruce, settled in Fulham, west London, during the Edwardian era when very few black people lived in Britain. He came here from British Guiana (now Guyana) a colony in South America. He was a proud, independent man.

Aunt Esther left school at 14 to work as a seamstress and in the 1930s she made dresses for the popular black American singer Elisabeth Welch. After Joseph was killed during an air raid in 1941, Aunt Esther was 'adopted' by my (white) great-grandmother, Granny Johnson, a mother figure in their community.

Esther said, 'She was like a mother to me. She was an angel.' For the next 11 years Aunt Esther shared her life with Granny (who died in 1952) and became part of our family.

During World War 2, Aunt Esther worked as a cleaner and fire watcher in Brompton Hospital. She helped unite her community during the Blitz and having relatives in Guyana proved useful when food was rationed.

She said, 'Times were hard during the war. Food was rationed. Things were so bad they started selling whale meat, but I wouldn't eat it. I didn't like the look of it. We made a joke about it, singing Vera Lynn's song We'll Meet Again with new words, "Whale meat again!" Often Granny said, "We could do with this. We could do with that." So I wrote to my dad's brother in Guyana. I asked him to send us some food. Two weeks later a great big box arrived, full of food! So I wrote more lists and sent them to my uncle. We welcomed those food parcels.'

In 1944 the Germans sent doodlebugs over. Said Aunt Esther, 'When the engine stopped I wondered where it was going to drop. It was really frightening because they killed thousands of people. A doodlebug flattened some of the houses in our street. Luckily our house was alright, even though we lived at number thirteen!'

In the late 1980s I began interviewing Aunt Esther and in the course of many interviews I uncovered a fascinating life history spanning eight decades. Aunt Esther gave me first-hand accounts of what life was like for a black Londoner throughout the 20th century. A friendly, outgoing woman, my aunt integrated easily into the multicultural society of post-war Britain. In 1991 we published her autobiography, Aunt Esther's Story, and this gave her a sense of achievement and pride towards the end of her life. She died in 1994 and, following her cremation, my mother and I scattered her ashes on her parents' unmarked grave in Fulham Palace Road cemetery. Granny Johnson rests nearby.

Contributed originally by ageconcernbradford (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People`s War site by Alan Magson of Age Concern Bradford and District on behalf of Malcolm Waters and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site`s terms and conditions.

The war against Germany was declared in 1939.

My parents had already separated, fortunate for me I stayed with my Father and my Sister Nora went with Mum.

Nora was really my half sister 6 years my senior yet I never looked on her other than my whole sister.

Nora’s name was Robinson, my Mother’s maiden name. Nora eventually left home to join a circus.

Dad, an ex regular soldier, who served with the Northumberland Fusiliers in the first world war, there was very little he could not put his hands to. He baked all our bread, a brilliant gardener, was a very good cook and kept our home spic and span.

Sadly he rarely talked about his life so I really never found out much about him. I know he was a Geordie and had a brother Billy, but what part of Newcastle I have no idea.

End of January 1940 was a very bad winter. Dad jumped off the running board of a bus, slipped and struck his head on the kerb. He had a stroke and died on the 10th February in St Johns Hospital, Keighley.

Going down Airwarth Street my Uncle Joe told me my Dad was dead. His last words were the start of my Christian name MAL then he passed on. I must emphasise the point my Dad was a brick, he lived for me. I did cry at night when I was alone, realising I would never see or hear his face or voice again.

My life changed so much that at times I lived with my schoolmate Ken Smith, we both worked in Edmondson`s Mill, Keighley as doffers. The foreman threw a bobbin at me as I was sat on a bobbin box and I threw as many back at him and got the sack.` I left to work in a steel works shovelling steel into a foundry, then I did some lumber jacking at Oakworth, Keighley. I ended up at Doublestones Farm in service above Silsden for the Fothergills. I spent six months from 5am until 11pm at night building walls, shearing sheep, dipping sheep, harnessing the horse, burying dead sheep, milking the cows, feeding and mucking out.

Keighley was normal, one hardly knew a war was on, working on a farm was even more remote. After six months farming, I asked Fothergill, can I go to Keighley Fair on Saturday afternoon. He said, “what am I going to do without you”. So I went to the fair and never returned to farming.

Mum and I went to London after the Blitz, even then night and day bombing was daily. You could hear the distinctive drone of Jerry as they gradually got nearer and the bombs got nearer. When we arrived in Fulham we had no money, looking for a Mrs Quinn who had left her flat leaving no forwarding address so Mum and I went knocking on doors until a Mrs Lampkin put us up. Mum was probably desperate having no money and no job. I must have been a burden to her.

I went to school at Ackmar Road with some of Mrs Lampkin’s boys. I adapted to life quickly and made the best of it. Mum then decided London was too dangerous, so she sent me to Ponterdawee South Wales as an evacuee. I well remember saying good bye to Mum stood on Paddington Station with my overcoat on, a label with my name and destination, my gas mask, identity card, ration books and teachers who were taking care of us. We arrived at night time in a schoolroom in Ponterdawee where our names were called out, a person stepped forward and took my hand a man and his son were my carers. I cannot remember their names, but his son was about my age so he taught me the ways of the Welsh. I quickly adapted getting free coal from the slag heaps. Taking the cows to the bull and getting diced cheese with brown sauce. I enjoyed my stay in Wales. I was treated very well.

Mum had established herself in Fulham she had a flat, then Nora came back into our lives again. She had blossomed into a bonny young woman who looked after me. At Ackmar Road schoolboys used to play pitch and toss, this was new to me as in Yorkshire gambling was not even on the cards. I can remember on Christmas going out singing carols to get Mum a Christmas card. She cried.

Nightly, the sirens went the whole sky was lit up with searchlights, I got fed up with getting out of bed. When Nora shouted of me to go down into the basement I said okay, you go on, I’ll follow you.

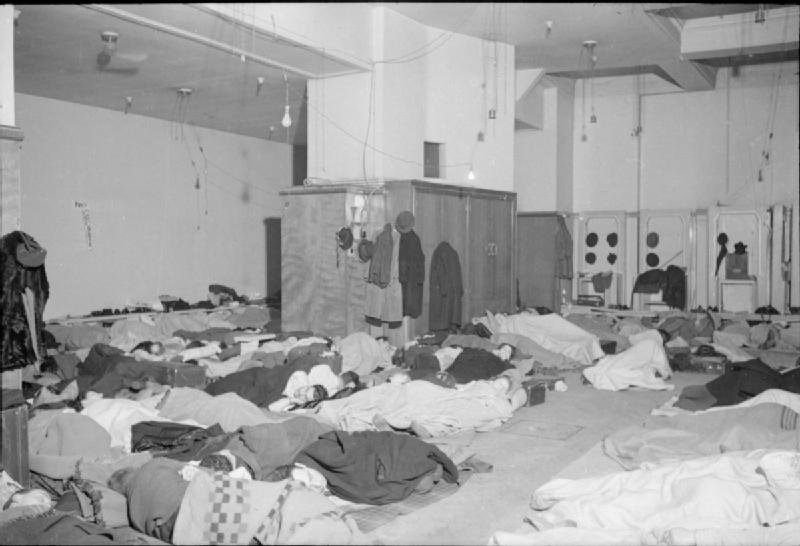

I could hear the bombers getting nearer and nearer, still lying in bed. Then I heard a whistling bomb that landed too close for comfort, my first reaction was to dive under the bed, my next reaction was to get down them stairs post haste. Nora was stood looking out of the back window, we were surrounded by buildings on fire. We were transfixed in awe at the blazing buildings, fire engine bells ringing, police cars whistles blowing, but we soon shot into the basement. Mum was on night work but the old lady always made us welcome. It got so bad at times we went to sleep on Piccadilly Station 75 feet below ground. Nora joined the ATS, I saw very little of her till later in life. One of the most frightening experiences was the mobile, ack ack guns that went off right outside our front door shaking all the windows. Most houses had stirrup pumps and buckets of sand just in case an incendiary came close.

Mum remarried a Peter Johnston from Tipperary In Ireland, he was an RSM in the Royal Engineers. He always respected me and was a real good family man, he always brought something home for me, but I am really a loyalist. I loved my own Father so much I could not accept another Dad, sad in a way, because he was a father of eight children who went in the Children’s Home in Keighley. They were all good children who’s mother fell down the stairs and broke her neck. Mum and I went to live in Townhead Glasgow to be near Peter who was stationed in Inverary. I went to school in Townhead I joined the Boys Brigade and was also a Lather Boy in a Barbers Shop. We got a bus from Robertson Street to Inverary went up the Rest and be thankful to arrive to see some real military movement. Assault craft, vehicles running backwards and forwards obviously getting ready to go to Dieppe. I slept in a huge bell tent while Mum and Peter went off to a Hotel. Peter was a very musical man he ran the Isle of Capri Band up Woodhouse, Keighley, an accordion and kazoo band who were very very good, they won many cups and shields, parading them around the Wood house Estate (pre War)

Back in London again in OngarRoad, Mum had a flat. Peter committed bigamy so Mum was on her own again. I remember going back to Keighley to spend my last days at Holycroft Board School, then back to London again. I got a job with the Civil Defence at Chelsea Town Hall and joined the London Irish Rifles Cadet Corps at Chelsea Barracks as a cadet soldier. As a messenger boy in the Civil Defence I cycled round the streets in uniform and my steel helmet on to various people of notoriety including the Chelsea Pensioners. Mum got a job in Peterborough looking after a man and his son, again his son was around my age, he was a brilliant young artist. He drew Peterborough Cathedral very professional. One day I went to Yewsley right next to the American Fortress Base. Looking up in the sky I could see and recognise a Jerry plane diving straight toward the street I was in. I ran like hell resting behind an Oak tree in a church yard watching the plane strafing the main street with cannon shelling, a close call.

I also worked in Dubiliers factory at Acton, making gallon petrol cans and we listened to " Music While you Work ". I also in Grosvenor House,Park Lane as a paticia`s assistant and the Americans occupied the hotel in the war years.

While in the Civil Defence I saw vapour trails of V2 rockets that landed somewhere toward Westminster. I went to Romford one night to stay at Harry`s, my mate`s house, as usual the sirens went moaning Minnie. It was like watching a film show looking over London with the bombers dropping canisters full of incendiaries. I commented to Harry, someone is getting a pasting, I found out Fulham had been hit again, a friend of Mum’s showed me his burnt shoes caused by kicking an incendiary out of the house. Everywhere was devastation, doors burned, windows blown. One chap, playing the piano had an incendiary pass through the roof straight between him and the piano into the next floor. I went to Putney one day, as normal, sirens sounded, my bus stopped on Putney Bridge, coming up the Thames was a V1, a buzz bomb, I watched it from the top deck coming right above the bus. The engine stopped. I watched it glide into a block of flats at Barns Bridge. I had the windows open, I felt the blast on my face from approximately half a mile away. One day I saw a squadron of 13 V1’s passing overhead in Gloucester Road, South Kensington.

The Army used to train on Harden Moor leaving unexploded bombs lying around. Two of my schoolmates playing with an unexploded PIAT bomb were blown to pieces in Lund Park, Keighley. Another friend Alec Joinson tried to saw through a grenade detonator, his face and arms were pitted with splinters he was covered in Sal volatile and was partially deaf.

I was very very lucky boy to be here to tell my story, I picked up a pop bottle that looked like bad eggs, fortunate for me I did not have a bottle opener so I through the bottle into a quarry. You should have seen the bright yellow phosphorous I’d picked up a Molotov cocktail, a phosphorous bomb.

Nora, my Sister, was in an air raid shelter that was hit and became flooded. She developed pneumonia then consumption. She spent many years in hospital and despite doctors warnings she had two children. At 43 neglected by her husband, she died and was cremated in Norwood Crematorium. She was a very very good mother who wasted away to a living skeleton. She spent many months in Brompton Hospital, I made all the funeral arrangements, the husband pleaded ignorance. I always enjoyed going to see her in London when I returned to Keighley later in life. I loved Nora very dearly and she never complained about all she suffered. Tommy Junior and Jenny still live in London, at Herne Hill. I occasionally call to see them.

The spirit of the Londoners in those dark days was second to none. We sang on the stations. I sang on Keighley Station when Ken Smith’s Father in Full Service marching order was off to Dieppe. Everyone sang “ wish me luck as you wave me goodbye” and “for a while we must part but remember me sweetheart “. Vera Lynne, Ann Shelton, Tommy Trinder, Arthur Askey, Flanagan and Allen and the Crazy Gang all made for good entertainment. Not forgetting George Formby and Grace Fields.

I am now 76 years old. Today I doubt the law would look on a single man like my Dad and the Gentleman in Wales as being capable of taking care of a family.

Contributed originally by BBC LONDON CSV ACTION DESK (BBC WW2 People's War)

"I'm a cockney born in Kingsbury Road near the Ball's Pond Road in the East End in 1937, so I was like 4, 5 and 6 when all this happened. I went to a Catholic School and during the Blitz when the air-raid sirens went, we'd get under the table and our teacher would say 'now you've got to pray' so we all prayed until the all-clear went.

One morning at 3, my mum's sister cam in and said 'there's a big bomb dropped near the old lady's house - that's what we called my gran - but she said she's all right. We rushed down the road and saw that a bomb had dropped on a school. I'll never forget, there wasn't a window left in none of the houses around. We went into a schoolhouse, the door was wide open, and there was blind man upstairs which they got our early; the whole ceiling had come down on him. We went into the kitchen and there was only about three bits of plaster left. The plaster round the rose on the ceiling was about the only bit left. I asked the blind man if he was okay and he said 'yeah' so I made him a cup of tea. We was lucky because if that bomb had dropped at three o'clock in the afternoon it would have killed all the kids.

I'll never forget this, the front door swung open and a fireman stood there. He said 'Everyone all right?' and one of the women said, well, I can't say what she said, but to the effect of 'that xxxxx Hitler can't kill me!'

We lived off the Ridley Road at the time and during one of the air raids one night, everyone went down the shelters and my dad said to me "Want to watch the airplanes?' My mum said 'That's not a good idea', anyway, he put me on his shoulders and we stood in the doorway and watched the dog-fights overhead. And I tell you, when them German planes got caught in the headlights, they had a hell of a job to get out. Anyway, the morning after these raids, all us kids'd go out collecting shrapnel from the shells, I had a great big box of the stuff.

Was I scared? Only when I was in bed at night and the air-raid warning went. When you're asleep and you suddenly woke, you didn’t' know what was happening so it was pretty frightening. At that age, you didn't know what air raids were all about. Some of the time I slept in the cupboard under the stairs and it felt a bit safer there.

One day, I went round to the corner to my aunt's house and she was sitting by the window when there was an air-raid warning. Inside the window where she was sitting was a table with a statue on it. They told her to come in away from the window. I'll never forget this, there was a bomb blast, the window come in and the statue toppled off the table and onto the floor. If she hadn't have moved, she'd have been covered with flying glass.

My dad didn't go in the army, because he was wanted on the railways. He took me down the dog racing one day at Hackney Wick. This flying bomb - a doodle-bug it was - suddenly appeared over us. You could see every detail of it. We all ran. It went right across the track and dropped in a field somewhere.

One day a landmine dropped near us in Kingsbury Road and didn't go off. A fellow came down from the Bomb Disposal unit, to try to disconnect it and he got killed. Opposite us there was a block of flats and they named it after him - Ketteridge Court.

I was evacuated for a little time, to Kettering, but I don't remember much about it, only that I didn't like it. I'd have to ask my mum about it. She's 100 but still remembers everything.

Me and my family are Pearly Kings and Queens and we do a lot of charity work, entertaining with music and the old cockney songs and that (Phone 020 8556 5971). We are now the biggest 'Pearly' family, made up mostly of the Hitchins (my mum's family name) in Hoxton, Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Clapton, Shoredich, Hommerton, Dalston, City of London, Westminster, Victoria, Islington and Stoke Newington. "

Contributed originally by epsomandewelllhc (BBC WW2 People's War)

The author of this story has understood the rules and regulations of the site and has agreed that his story can be entered on the People's War web site.

A FLYER'S STORY

When war broke out I was working for the Phoenix Assurance Co in the City. I decided to volunteer for the Air Force - to avoid going into the army!!

In May 1940, I was summoned to Cardington to be attested. This consisted of having interviews and a thorough medical examination; and then swearing an Oath of Allegiance to King George VI, his heirs and successors. Finally I was given the rank of Aircraftsman 2nd Class and a number 1161718. Some weeks later I had to give my name and number to a Corporal who said “that’s not a number, it’s the population of China! As far as rank was concerned, I had eight during my six years with the RAF, ending up as a Flight Lieutenant.

In September 1940, I was sent to the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Hatfield, learning on Tiger Moths. While I was there, an incident occurred which still sticks in my memory. One particular day in October, was a day of low cloud and strong winds and all the Tiger Moths were grounded. All the members of the course were therefore given extra lectures/ Suddenly during a lecture, there was the sound of a low flying aircraft flying across the airfield. One young cadet, looking out of the window said “That’s a Junkers 88” There were cries of derision and some said “It’s a Blenheim” Almost immediately the air raid siren sounded and we all dashed for the shelters. Before we could reach them, the Junkers 88 returned, flew across the airfield, was hit by flak, but dropped four bombs on the de Haviland factory at the far end, causing several casualties and great damage. Many years later, I learned that the new super aircraft, the Mosquito was being built there. I have reflected since, that the crew of the Junkers 88 were brilliant navigators or very, very lucky.

When being trained by Flying Officer Kelsey at Hatfield, he often used to ask pupils to practice a forced landing in a field as if your engine had failed. He did this with me twice, but we found he had an ulterior motive: when we had landed in the field, he jumped out of the Tiger Moth and said `follow me'. I taxied the aircraft round the field to take off again and he would be walking along picking mushrooms. He was very fond of mushrooms and took them back to the mess for his breakfast!!

One of the rather sad things was that at the beginning of every course, which included about 50 men, they always took a picture of all the pupils and that was partly because it was recognized that some would not survive. If you went into a training establishment after the war had started, you would always find some of those in the pictures with little haloes drawn over them - they were the ones who had died. There would be up to about five in the 50 who wouldn't make it. I can't really remember a group photograph where no one had been killed.

I was at Hatfield for about 6 weeks and then went to Hulavington, Wilts. where I was flying Hawker Harts and got my wings.

I finished my training at Sutton Bridge on Hurricanes. I found Hurricanes very difficult to start with. The others were biplanes and this was a monoplane and flew at least twice as fast. The feel of it was very different and seemed to me to be going terribly fast, but when I got used to it, I did like the aircraft. On the other hand, it was somewhat more unstable than the Spitfire and required much more active hands-on flying, whilst a Spitfire when trimmed properly was much easier to handle and in good weather would almost fly itself.

For the next 6 months after training, I went to a fighter squadron in Orkney, where it was very bleak and the wind never stopped. The fighters were there firstly because of Scapa Flow and secondly to try to stop the Germans flying out into the Atlantic. They had big aircraft called Condors as well as Junkers 88s. There is a gap of about 100 miles between Orkney and Shetland which needed covering. The Germans didn't want to go right up to the north by Iceland. There were two fighter squadrons stationed up there, one on Orkney and the other was split between the Scottish mainland and Shetland, to cover these two jobs.

Was I afraid? Not usually. It is true to say that your training gives you confidence which carries you along quite a bit but there is also a feeling that it will always `happen to the other fellow' and you don't think about injury or death happening to yourself, except if you are actually in the middle of a very nasty situation. It something you just get used to.

My next job was as an instructor for almost a year at an Operational Training Unit to teach on Hurricanes and Spitfires. All the pupils already had their wings. The thing is, a Hurricane is a one-seater so you couldn't sit in with a pilot, but there was a Miles Master which was similar to the Hurricane but was a two-seater. The Instructor sat in the back and the pupil was in the front and the most important things to learn were taking off and landing. When you thought they could manage, you sent them up on a solo in a Hurricane with fingers crossed and hoped they could do it.

After leaving the OTU I did some Army co-operation work and some aircraft delivery.

I then transferred to 1697 flight at Northolt in July 1944. This was called Air Despatch Letter Service. We had Hurricanes specially adapted to carry mail. They had a special space behind the pilot and it was also possible to use one of the under--wing fuel spaces for mail. The object of this was to fly despatches from Normandy back to London. We used to fly the Hurricanes in to the airstrips and despatch riders would come from the front bringing despatches for London. It took about an hour to fly the distance back to Northolt where another despatch rider or driver would take it straight in to London, so an action which might have taken place at 7 a.m. would be reported in London by about 10 a.m. This practice gradually spread a11 over Europe as the armies advanced. We advanced with them, flying to the nearest airstrip and collecting despatches for home.

On 26 August 1944, I flew information from Balleray in France to Northolt all about De Gaulle's entry into Paris and it was very interesting to see it in the papers the next day, knowing that I had carried it in.

VE Day was very busy and I made three flights on 8 May, flying from Germany to Holland and Holland to Northolt and then back to Germany. During the post-war period we were even busier than before with mail and information, clocking up a lot of flying hours. It was during this time that I was able to have a little flight on a Focke Wulf 190 which we had captured. It was very interesting but was extremely fast and it was a little unnerving in a way because there was so much electrical equipment. Instead of levers many of the controls were just little buttons so you controlled it very tentatively hoping it would do the right thing.

My last flight as a member of the Royal Air Force was in a Spitfire on 5 April 1946 but in 1953 I did some flying at Redhiil as Air Force Reserve, because I have to admit, I missed flying. However, I finally stopped flying in May 1953 and have not flown since. I totaled up 1527 hours of which I would think half was in Hurricanes.

I didn't find running the mail dull. I enjoyed pilot navigating, taking myself from one place to another. When you trained, you did cross-country flights and set a course from A to B using landmarks to help you along. If it was bad weather, you came below the clouds and if it was too bad, you just couldn't fly. You did have radio to help you, but it was very unreliable so you needed to be able to manage without it. The airstrips were just that -just a cleared field with a runway laid by engineers. You just had to find it by checking the little villages and knowing which ones they were.

Coming in from the sea you could check where you were as you crossed the coast by the shape of the coast and the placement of the villages.

You soon learned not to get lost but it was possible to do so. The first time I took out a Spitfire - in England, fortunately - I got completely lost because it was so fast. When I looked back the place I took off from was gone. I was in rather a panic but I should have realized that by flying west to the Welsh coast and turning right I would have got to Carlisle which is where I was supposed to be going. I didn't think of it because I was in a panic but that was early on in about 1941 before I got used to finding my way. I landed at an airstrip I found and tried again. Not a very good example of good airmanship! ! !

When we weren't flying, we didn't do very much really. There were always a few of us about for company. We used to stay on the aerodrome mostly. We might mooch up and chat to the Air Controllers to see what was happening and if anything interesting was coming in. When we used to fly to Germany, later on, there was a big aerodrome built which had a lot going on. We lived in a little house with a stream behind which was lovely and a nice area to go for walks. There were very few female personnel about. However, fraternising with local German girls was very much discouraged. After the war was over, we were still there for quite some time and there used to be dances which female service personnel used to attend, which were very nice, but overall it was a very masculine life. We used to be wrapped up in flying and aircraft very much and I must say I was never bored.

It is said that some people found it very hard to settle dawn to civilian life again but I can't say I had any difficulty. To be honest, after risking your neck to some extent for six years, it was quite nice to be able to say you were going to live a normal life again.

I was very fortunate in being able to go back to my job at the Phoenix Assurance Co. First of all, they had a rule that no married women could work at the Phoenix, but they did relax that later. They were a very good company and even paid us while we were in the services. Before the war my salary was £120 a year, but even during the war they paid about £60 p.a. When I came back to work for them, my pay was £300 p.a. That wasn't a lot, but you could get married on that. In fact, I met my future wife at work a few months after I returned.

Arthur Lowndes AFC