High Explosive Bomb at Thessaly Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Thessaly Road, Battersea, London Borough of Wandsworth, SW8 4XH, London

Further details

56 18 NW - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by DOUGLAS ROTHERY (BBC WW2 People's War)

Chapter XI - A Proud Epitaph

Shelling had now become extremely intensive and have been warned to expect a counter attack. A tank to our front was a blazing inferno and was close to a stone built barn, two of my Section requested permission to go to the toilet and they ran to the stone barn, but no sooner had they disappeared inside, it was hit simultaneously by two shells and we couldn't see the barn for a cloud of dust. I was thinking well that's their lot, when out of the dust two figures emerged running like the clappers holding up their trousers, as you can imagine we roared with laughter especially when one them said, 'It was a sure cure for constipation'.

I am not exaggerating when I say that for every minute of the day and night the shelling and salvoes of rockets from the Moaning Minnies were terrifying, one continuous barrage, I have never known such a concentration before on such a comparatively small area. We could hear women and children screaming in terror in the houses to our rear many of which were ablaze, lighting up a moon-less sky. This barrage was still continuing in the morning with the same ferocity, no let up, it was most traumatic and horrifying witnessing this onslaught without any means of personal retaliation but just standing there awaiting the chance perhaps of a reciprocal respite when given the order to advance, these experiences cannot be expressed in words or films. Our exact map location at that very moment I hadn't the slightest idea mainly because Section leaders are not in possession of such, what I did know is that our presence was not at all entente cordial.

Regardless of this slaughter taking place around us, out comes Dad, God bless him, with our mess tins of precious sustenance, dumps it, then scurries back to where he has hidden our vehicle. No sooner had he done so, we sat down on the floor of the trench to partake of our meagre breakfast, leaving Gdsm: Bowse standing on guard and acting waiter. He was in the process of handing me my mess tin by reaching over two others when there was an almighty explosion. I was flung backwards by a terrific force and momentarily stunned. There was a few seconds silence ,then I called on the Mother of God for divine intervention and succour. I eventually could see out of one eye my hearing was naturally impaired, blood was pouring down my face, my arms felt stiff and numb, the front of my tunic was ripped away and both sleeves were in tatters. The poor unfortunate who was leaning over to me, Guardsman Bowse was killed, two others were injured no doubt his body protected us from more serious injuries. I was to learn some time later that a rocket shell had hit the perimeter of the trench so if it had happened a few seconds before we would have been all standing up. Someone put a bandage around my head and eyes and helped me and others into a vehicle which took us to the First aid post about a mile back. They cleaned me up a bit, re-bandaged my head and eyes, put both arms in slings then put me in an ambulance to be taken to the base hospital. No sooner had I laid down in the ambulance than I felt a joy of relief, everything seemed so peaceful, just the rumbling of shell fire in the distance as I gradually unwound from the tension and trauma of hell plus the fact I couldn't remember when I slept last, I was certainly going to make up for it as I went completely out.

Waking up as the cold air hit me, I was carried in on a stretcher into the Base hospital which was a very large marquee somewhere in France. After being put to bed a doctor along with a couple of others gave me a thorough examination and removed the slings from my arms. Apparently my chest arms and face were like a pepper pot caused, according to the doctor, by fragmented stones, these he said would eventually come to the surface and was nothing to worry about and were also in the muscles of my arms causing them to be stiff.

I remained in bed for about 3 weeks whilst they treated my ears and eyes and eventually allowed me to go to the washroom which was the first chance I had of seeing my face and it was a peculiar experience because I didn't recognise myself. Apart from it being peppered it was blown up like a balloon caused by the blast and my eyes were just slits, it was a bit of a shock. They seemed quite concerned about my eyes more so than my ears, which has left me with a steam train passing with its whistle blowing.

Whilst here I felt very proud when other patients on hearing that I was a Grenadier would come over to congratulate me on the achievements of the Guards Armoured Division. ( Div: sign:-- 'The Ever Open Eye'), a sign by looking at me, that must have seemed a contradiction.

This also gave me the opportunity to reflect on the trauma an infantry man uniquely experiences, yet at the end of his stint is not even given any more consideration to those who although not in earshot of enemy action are entitled to the same Campaign recognition which to me makes the medal significance less rewarding. (The powers that be I imagine would say 'You were only doing what was expected of you").. Shame.

After about six weeks I was informed that I along with others were to be flown back to Blighty, I was elated. One morning I along with about ten others, some on stretchers, found ourselves in the corner of a field where there was a lone Dakota, it wasn't long before we were up and away. Flying low over the channel to escape radar detection and on nearing the home coast we climbed, it was a wonderful feeling looking down on a peaceful countryside bathed in sunlight so much so I pointed this out to a fellow on a stretcher whom I expected to share my enthusiasm but he only gave me a scornful look. I then realised he was a Jerry.

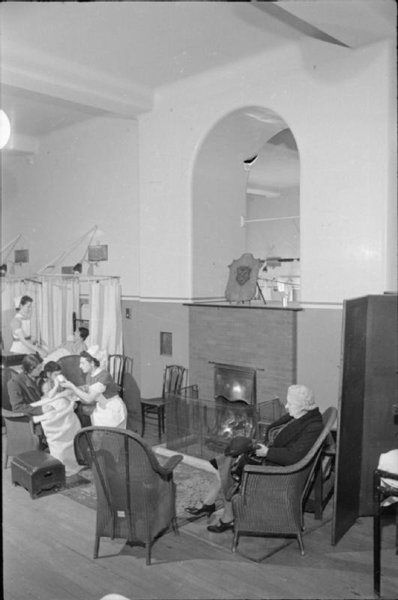

We landed somewhere in West Bromwich because it was to a hospital there where I was to stay for a short while, thank goodness! It was very primitive. I was then transferred to a Birmingham hospital where I was eventually allowed out in regulation hospital blue and red tie thus giving me the opportunity to visit an Aunt. I was then transferred to Leamington Spa to the 'Home for the Incurables.' I hasten to add that service personnel were in a separate ward. Each evening a Victorian battle-axe of a matron would literally march through the ward with her entourage, who endeavoured to keep up with her, whilst the patients that were able, had to stand at the foot of their bed until she had passed through, you then had to go to bed. As there were no radio or headphones in the ward we naturally, being interested in the progress of the war sought permission to be allowed to hear the 9pm news in the Rest room, this was refused because it would upset the procedural practice carried on in the hospital for decades. It was decided that it was about time the rules were changed, so come 9pm we would sneak downstairs until one night we were reported. To cut a long story short I was appointed as spokesman and had to appear before the Head Administrator who threatened to report me to the army authorities, I likewise their draconian method of administration. We were granted permission to hear the 9pm news with a promise of headphones for each bed.

After a few months I was sent to Stoke-on-Trent convalescent army camp where after being issued with new clobber I was to meet up with many of my mates now patched up and eager to get back at the enemy. (If you believe that you will believe anything). I was very surprised to meet R.S.M Hufton who had certainly mellowed after his battle inoculation, I didn't know he had been wounded. He called me over and asked me what I was doing that afternoon. I nearly said 'I didn't know you cared'. Anyway he treated me to a football match between Stoke and Portsmouth and afterwards to a Cafe for a tea and a wad. 'There you are, they are human after all'.

After idling our time away here for a few weeks all Grenadiers were sent to Victoria barracks Windsor where I was to meet up with more patched up heroes straining on the leash, but before doing so there was much reminiscing over pints with old acquaintances, one of them being a Sergeant Twelftree who was a pall bearer at the funeral of HM King George V and was one of my buddies when we first went out to France so we had plenty to celebrate about. Unfortunately they were all to rejoin their units with the exception of Corporal Griffiths ex heavy and light heavy weight Brigade boxing champion who, like me was now downgraded to C2 and was to be my Corporal of the guard at the barracks one night. On reveille, Griffiths on dismounting the sentry, (who by the way was a recruit,) marched him into the guardroom and gave him the order to unload and in doing so the recruit inadvertently left a round up the breech and on pressing the trigger the bullet went into the ceiling scattering plaster all around the guardroom much to the amusement of Griff; who was curled up in muffled laughter behind him. The Picket officer a [Young Chicko] walked in immediately afterwards and I thought he had heard the report but apparently hadn't, which I imagined should have woken up all of Windsor, but he was just checking the Tattoo report as part of his duty by asking 'Everything all right Sergeant'. He didn't look anymore than 18yrs old and was at the same time walking around the guardroom tapping the plaster from side to side with his stick. When I explained what had happened he just said 'Oh, oh railly, oh, oh' and off he went. The recruit got off with a reprimand, I believe the shock it gave him was ample punishment.

Whilst here I received a Regimental Christmas and New Year card with the Divisional sign of the Guards Armour (the ever open eye) on the front cover, the card denoted the capture of Nijmegan among other battle honours and it was sent to me by L/Cpl Cox(Nobby) who was one of my Section before he got promoted. I was to learn later that he must have been killed whilst the card was in the post. 'God Bless'.

I was talking to a group of Americans who dressed in their army uniform were waiting at the main gate and had apparently arrived back from France the day before,and I asked them how much they enjoyed the luxurious accommodation of Victoria barracks, I am afraid their response wasn't at all complimentary. They said they were the Glen Miller band and were awaiting their leaders arrival. His disappearance to this day still remains a mystery.

Being downgraded, all that my duties comprised of here were Sergeant-In-Waiting and Sergeant of the barrack guard roles, so R.S.M. Snapper Robinson I should imagine decided that I might have some undiscovered talents which were not forthcoming here because he passed the Buck and me with it to 'Stobbs camp' near Hawick where I was to discover to my amazement, my mate of old standing Dennis Ward of No5 Section who told me that soon after my encounter he was shot receiving a bullet wound in the shoulder and was now pronounced fit enough to be shot at again and therefore was training with a contingent of Grenadiers for Far Eastern engagements.

I don't believe their gastronomic considerations were very high on their priority list because I was sent to H.Q Company to be in charge of their rations where each week I along with a driver in a 15cwt truck would have to proceed to Edinburgh to buy from the N.A.A.F.I. store, an amount determined by the manipulation of an allowance considered enough to sustain about fifty or so hungry warriors. One particular morning I was informed to report for Company Commanders Orders where I was expecting to be formally told that I had been recommended for promotion, unfortunately on meeting the Company Commander, he had just discovered at this late hour, that I was not A.1 and therefore was extremely sorry but it must be denied me. If the reason for not being upgraded was due to unsatisfactory ration distribution or whatever, I might have understood, but the lesson to be learnt is, when you go into battle, Its not only your life that is on the line but also your promotion so for goodness sake keep your head down. My ambition to join the Police when hostilities ceased was also shattered. Regardless of these adversities, I am proud to say my compensatory reward was having been in the company of wonderful comrades who also experienced the honour of being contributors to the historical glory of an equally glorious regiment

Whilst I was here peace was declared in May 1945 so my rationed superior recipients either seeking revenge or the alternatives to prunes and custard each Sunday lunch, decided to transfer my expertise to( Sefton Park) Slough where I was to remain until my demobilisation and in keeping with the usual Service administrative protocol, I was sent to the furthest point in the South of England, 'Penzance' Demobilisation Centre instead of the one close by namely Reading.

On arrival I was to be very disappointed with the few suits available and when I mentioned this they were very apologetic and came out with the old cliche, 'If sir would come back tomorrow when they were expecting a new consignment', Some hope! No homing instincts were to dominate my dress sense and I was to choose one I considered less conspicuous of the few remaining, a blue serge, which I am sure was made from a dyed army 'U' blanket in which I furtively crept away in, with the princely sum of 75 pounds for which I signed for. So after completing 8yrs with the colours because of the war, instead of the 4yrs in which I enlisted, I was to return home on the 2nd of March 1946 at the age of 26 years to the same establishment in which I left to join up.

That said, I reflect with sadness but with tremendous pride the heroic memories of those whose supreme sacrifice along with their past comrades, have contributed so generously and honourably to the proud epitaph of "THE BRITISH GRENADIERS".

2615652 EX L/SGT ROTHERY. D.. Arthur Baker survived the war after serving his time in the 3rd Batt:and we were never to meet up again until approx; 10yrs after joining the army together. He was married and lived in Guilford

Contributed originally by BBC LONDON CSV ACTION DESK (BBC WW2 People's War)

"I'm a cockney born in Kingsbury Road near the Ball's Pond Road in the East End in 1937, so I was like 4, 5 and 6 when all this happened. I went to a Catholic School and during the Blitz when the air-raid sirens went, we'd get under the table and our teacher would say 'now you've got to pray' so we all prayed until the all-clear went.

One morning at 3, my mum's sister cam in and said 'there's a big bomb dropped near the old lady's house - that's what we called my gran - but she said she's all right. We rushed down the road and saw that a bomb had dropped on a school. I'll never forget, there wasn't a window left in none of the houses around. We went into a schoolhouse, the door was wide open, and there was blind man upstairs which they got our early; the whole ceiling had come down on him. We went into the kitchen and there was only about three bits of plaster left. The plaster round the rose on the ceiling was about the only bit left. I asked the blind man if he was okay and he said 'yeah' so I made him a cup of tea. We was lucky because if that bomb had dropped at three o'clock in the afternoon it would have killed all the kids.

I'll never forget this, the front door swung open and a fireman stood there. He said 'Everyone all right?' and one of the women said, well, I can't say what she said, but to the effect of 'that xxxxx Hitler can't kill me!'

We lived off the Ridley Road at the time and during one of the air raids one night, everyone went down the shelters and my dad said to me "Want to watch the airplanes?' My mum said 'That's not a good idea', anyway, he put me on his shoulders and we stood in the doorway and watched the dog-fights overhead. And I tell you, when them German planes got caught in the headlights, they had a hell of a job to get out. Anyway, the morning after these raids, all us kids'd go out collecting shrapnel from the shells, I had a great big box of the stuff.

Was I scared? Only when I was in bed at night and the air-raid warning went. When you're asleep and you suddenly woke, you didn’t' know what was happening so it was pretty frightening. At that age, you didn't know what air raids were all about. Some of the time I slept in the cupboard under the stairs and it felt a bit safer there.

One day, I went round to the corner to my aunt's house and she was sitting by the window when there was an air-raid warning. Inside the window where she was sitting was a table with a statue on it. They told her to come in away from the window. I'll never forget this, there was a bomb blast, the window come in and the statue toppled off the table and onto the floor. If she hadn't have moved, she'd have been covered with flying glass.

My dad didn't go in the army, because he was wanted on the railways. He took me down the dog racing one day at Hackney Wick. This flying bomb - a doodle-bug it was - suddenly appeared over us. You could see every detail of it. We all ran. It went right across the track and dropped in a field somewhere.

One day a landmine dropped near us in Kingsbury Road and didn't go off. A fellow came down from the Bomb Disposal unit, to try to disconnect it and he got killed. Opposite us there was a block of flats and they named it after him - Ketteridge Court.

I was evacuated for a little time, to Kettering, but I don't remember much about it, only that I didn't like it. I'd have to ask my mum about it. She's 100 but still remembers everything.

Me and my family are Pearly Kings and Queens and we do a lot of charity work, entertaining with music and the old cockney songs and that (Phone 020 8556 5971). We are now the biggest 'Pearly' family, made up mostly of the Hitchins (my mum's family name) in Hoxton, Tower Hamlets, Hackney, Clapton, Shoredich, Hommerton, Dalston, City of London, Westminster, Victoria, Islington and Stoke Newington. "

Contributed originally by epsomandewelllhc (BBC WW2 People's War)

The author of this story has understood the rules and regulations of the site and has agreed that his story can be entered on the People's War web site.

A FLYER'S STORY

When war broke out I was working for the Phoenix Assurance Co in the City. I decided to volunteer for the Air Force - to avoid going into the army!!

In May 1940, I was summoned to Cardington to be attested. This consisted of having interviews and a thorough medical examination; and then swearing an Oath of Allegiance to King George VI, his heirs and successors. Finally I was given the rank of Aircraftsman 2nd Class and a number 1161718. Some weeks later I had to give my name and number to a Corporal who said “that’s not a number, it’s the population of China! As far as rank was concerned, I had eight during my six years with the RAF, ending up as a Flight Lieutenant.

In September 1940, I was sent to the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) at Hatfield, learning on Tiger Moths. While I was there, an incident occurred which still sticks in my memory. One particular day in October, was a day of low cloud and strong winds and all the Tiger Moths were grounded. All the members of the course were therefore given extra lectures/ Suddenly during a lecture, there was the sound of a low flying aircraft flying across the airfield. One young cadet, looking out of the window said “That’s a Junkers 88” There were cries of derision and some said “It’s a Blenheim” Almost immediately the air raid siren sounded and we all dashed for the shelters. Before we could reach them, the Junkers 88 returned, flew across the airfield, was hit by flak, but dropped four bombs on the de Haviland factory at the far end, causing several casualties and great damage. Many years later, I learned that the new super aircraft, the Mosquito was being built there. I have reflected since, that the crew of the Junkers 88 were brilliant navigators or very, very lucky.

When being trained by Flying Officer Kelsey at Hatfield, he often used to ask pupils to practice a forced landing in a field as if your engine had failed. He did this with me twice, but we found he had an ulterior motive: when we had landed in the field, he jumped out of the Tiger Moth and said `follow me'. I taxied the aircraft round the field to take off again and he would be walking along picking mushrooms. He was very fond of mushrooms and took them back to the mess for his breakfast!!

One of the rather sad things was that at the beginning of every course, which included about 50 men, they always took a picture of all the pupils and that was partly because it was recognized that some would not survive. If you went into a training establishment after the war had started, you would always find some of those in the pictures with little haloes drawn over them - they were the ones who had died. There would be up to about five in the 50 who wouldn't make it. I can't really remember a group photograph where no one had been killed.

I was at Hatfield for about 6 weeks and then went to Hulavington, Wilts. where I was flying Hawker Harts and got my wings.

I finished my training at Sutton Bridge on Hurricanes. I found Hurricanes very difficult to start with. The others were biplanes and this was a monoplane and flew at least twice as fast. The feel of it was very different and seemed to me to be going terribly fast, but when I got used to it, I did like the aircraft. On the other hand, it was somewhat more unstable than the Spitfire and required much more active hands-on flying, whilst a Spitfire when trimmed properly was much easier to handle and in good weather would almost fly itself.

For the next 6 months after training, I went to a fighter squadron in Orkney, where it was very bleak and the wind never stopped. The fighters were there firstly because of Scapa Flow and secondly to try to stop the Germans flying out into the Atlantic. They had big aircraft called Condors as well as Junkers 88s. There is a gap of about 100 miles between Orkney and Shetland which needed covering. The Germans didn't want to go right up to the north by Iceland. There were two fighter squadrons stationed up there, one on Orkney and the other was split between the Scottish mainland and Shetland, to cover these two jobs.

Was I afraid? Not usually. It is true to say that your training gives you confidence which carries you along quite a bit but there is also a feeling that it will always `happen to the other fellow' and you don't think about injury or death happening to yourself, except if you are actually in the middle of a very nasty situation. It something you just get used to.

My next job was as an instructor for almost a year at an Operational Training Unit to teach on Hurricanes and Spitfires. All the pupils already had their wings. The thing is, a Hurricane is a one-seater so you couldn't sit in with a pilot, but there was a Miles Master which was similar to the Hurricane but was a two-seater. The Instructor sat in the back and the pupil was in the front and the most important things to learn were taking off and landing. When you thought they could manage, you sent them up on a solo in a Hurricane with fingers crossed and hoped they could do it.

After leaving the OTU I did some Army co-operation work and some aircraft delivery.

I then transferred to 1697 flight at Northolt in July 1944. This was called Air Despatch Letter Service. We had Hurricanes specially adapted to carry mail. They had a special space behind the pilot and it was also possible to use one of the under--wing fuel spaces for mail. The object of this was to fly despatches from Normandy back to London. We used to fly the Hurricanes in to the airstrips and despatch riders would come from the front bringing despatches for London. It took about an hour to fly the distance back to Northolt where another despatch rider or driver would take it straight in to London, so an action which might have taken place at 7 a.m. would be reported in London by about 10 a.m. This practice gradually spread a11 over Europe as the armies advanced. We advanced with them, flying to the nearest airstrip and collecting despatches for home.

On 26 August 1944, I flew information from Balleray in France to Northolt all about De Gaulle's entry into Paris and it was very interesting to see it in the papers the next day, knowing that I had carried it in.

VE Day was very busy and I made three flights on 8 May, flying from Germany to Holland and Holland to Northolt and then back to Germany. During the post-war period we were even busier than before with mail and information, clocking up a lot of flying hours. It was during this time that I was able to have a little flight on a Focke Wulf 190 which we had captured. It was very interesting but was extremely fast and it was a little unnerving in a way because there was so much electrical equipment. Instead of levers many of the controls were just little buttons so you controlled it very tentatively hoping it would do the right thing.

My last flight as a member of the Royal Air Force was in a Spitfire on 5 April 1946 but in 1953 I did some flying at Redhiil as Air Force Reserve, because I have to admit, I missed flying. However, I finally stopped flying in May 1953 and have not flown since. I totaled up 1527 hours of which I would think half was in Hurricanes.

I didn't find running the mail dull. I enjoyed pilot navigating, taking myself from one place to another. When you trained, you did cross-country flights and set a course from A to B using landmarks to help you along. If it was bad weather, you came below the clouds and if it was too bad, you just couldn't fly. You did have radio to help you, but it was very unreliable so you needed to be able to manage without it. The airstrips were just that -just a cleared field with a runway laid by engineers. You just had to find it by checking the little villages and knowing which ones they were.

Coming in from the sea you could check where you were as you crossed the coast by the shape of the coast and the placement of the villages.

You soon learned not to get lost but it was possible to do so. The first time I took out a Spitfire - in England, fortunately - I got completely lost because it was so fast. When I looked back the place I took off from was gone. I was in rather a panic but I should have realized that by flying west to the Welsh coast and turning right I would have got to Carlisle which is where I was supposed to be going. I didn't think of it because I was in a panic but that was early on in about 1941 before I got used to finding my way. I landed at an airstrip I found and tried again. Not a very good example of good airmanship! ! !

When we weren't flying, we didn't do very much really. There were always a few of us about for company. We used to stay on the aerodrome mostly. We might mooch up and chat to the Air Controllers to see what was happening and if anything interesting was coming in. When we used to fly to Germany, later on, there was a big aerodrome built which had a lot going on. We lived in a little house with a stream behind which was lovely and a nice area to go for walks. There were very few female personnel about. However, fraternising with local German girls was very much discouraged. After the war was over, we were still there for quite some time and there used to be dances which female service personnel used to attend, which were very nice, but overall it was a very masculine life. We used to be wrapped up in flying and aircraft very much and I must say I was never bored.

It is said that some people found it very hard to settle dawn to civilian life again but I can't say I had any difficulty. To be honest, after risking your neck to some extent for six years, it was quite nice to be able to say you were going to live a normal life again.

I was very fortunate in being able to go back to my job at the Phoenix Assurance Co. First of all, they had a rule that no married women could work at the Phoenix, but they did relax that later. They were a very good company and even paid us while we were in the services. Before the war my salary was £120 a year, but even during the war they paid about £60 p.a. When I came back to work for them, my pay was £300 p.a. That wasn't a lot, but you could get married on that. In fact, I met my future wife at work a few months after I returned.

Arthur Lowndes AFC

Contributed originally by Torbay Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Paul Trainer of Torbay Library Services on behalf of Benita Cumming, the daughter of Ben Cumming, and has been added to the site with her permission. Ms Cumming fully understands the site's Terms and Conditions.

On that fateful day in September of 1939, which fell on a Sunday, I heard on the radio that Britain had declared war on Germany, as that country had invaded Poland, and our country had a treaty with Poland to come to her aid. It came to my mind when I heard this that now was the opportunity for me to break away from the humdrum existence I was leading at that time and enlist to get away from it - providing the conflict lasted long enough for me to participate (the general opinion at the time was that it would be over by Christmas).

The next day in the local newspaper was an advert for young men, at least 5 foot 11 inches tall, who were wanted as recruits for the Brigade of Guards, and right away I thought, "That's for me!" The first opportunity I had, I was off to the Recruiting Office in Torquay and got signed on. I was given a railway warrant to get me to Exeter, where I went to the Army Barracks there, had a medical examination, passed and got accepted for the Grenadier Guards. I hadn't said anything at home about what I was going to do and when I got back that evening and told them the news, they were very proud of me but also very worried about what was going to happen to me.

I hung around for a few days saying my goodbyes, whilst I waited for a railway warrant to take me to London and Chelsea Barracks, the Guards Depot to where I had to report. My mates said I was crazy, but they all wished me well, and then I was off. It was late at night when I finally arrived at the Depot and was given a meal and put in a room with other new recruits, some of whom were to remain comrades with me for the next five or six years. It was all a very strange experience for me; the farthest I had ever been previously was a school trip to Swindon to view the Railway Sheds!

We did not see anything of the world outside for a couple of months as before being allowed out, recruits had to be able to walk properly as becomes a Guardsman. My Army pay was 14 shillings (70p) a week, of which I made my Mother an allowance of five shillings (25p) a week. After a few days we were issued with a pair of hobnailed boots and a khaki uniform with brass buttons, and on our legs from knee to ankle we wore puttees (strips of cloth). It was the same kind of uniform that troops who fought in the First World War wore. We did not get proper battle-dress until much later. I had to take a lot of stick from my new comrades because as I came from the West Country, they called me a Swede Basher and said that I had straw sticking in my hair.

The next few months were spent drilling and marching on the barrack square and being toughened up in the gymnasium, until we were considered to be fit and efficient enough to be changed from recruits to Guardsmen. We were then put on what was referred to as Public Duties - that is, going on guard at St. James' palace and Buckingham Palace. We also had to do guard on the bridges over the Thames as the I.R.A. were attempting to blow them up.

In early 1940, in the period known as the "phoney war", the Russians invaded Finland. Chamberlain, the then Prime Minister, had the crazy idea of sending an expeditionary force to go to the aid of the Finns. I was sent on embarkation leave prior to joining that force but fortunately the plan was scrapped; it would have been catastrophic if it had been allowed to

go ahead. However, I had gone on leave carrying all my equipment, including a rifle and ammunition. It was my first leave since joining up and the situation had changed a lot since I left home; Joan had left to join the N.A.A.F.I. and my parents could not keep up the mortgage payments on their house at Danvers Road. They had applied for and been granted a house, 23 Starpitten Grove, on the Watcombe Council estate. It was a nice little house, newly built in a cul-de-sac but miles from Torquay town. Sometime after I learnt that Father had been drafted away somewhere in the country, helping in the work of constructing an Army camp. Mother was left on her own and she had to take in some evacuees from the East End of London, two or three boys I think, and I gather they were a right bunch of hooligans. My sister Mary, or "Blossom" as she was known, came to live with her, which made life a little easier for Mum.

The early spring saw the invasion of Belgium by the Germans, and British troops were rushed to the border of France and Belgium to try to stem them, but they were brushed aside and had to retreat, eventually to be evacuated from Dunkirk. The Luftwaffe began their bombing campaign and the Battle of Britain had commenced; the fear in this country was that the German army was about to mount an invasion as barges had been spotted moored at ports on the French coast across the English Channel. There was also the possibility that parachutists would be dropped in great numbers on strategic targets. My mob was the holding Battalion and we were stationed in London for the defence of that city and we were put on alert to counter the dropping of any airborne troops.

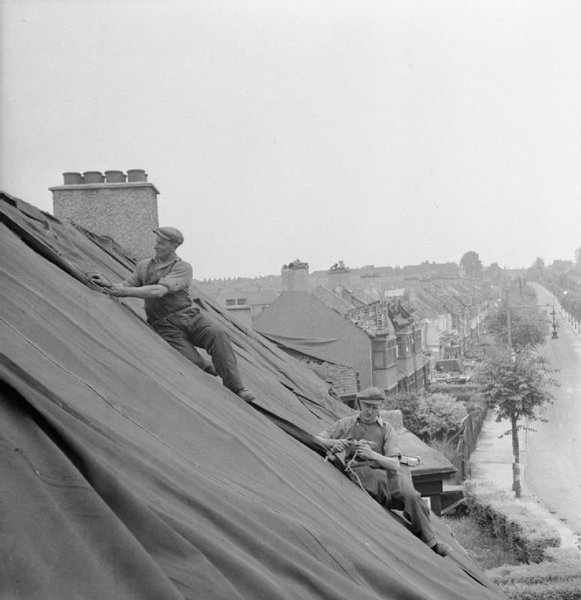

One duty was being taken by military transport to various Police stations in the Metropolitan area and two Guardsmen would ride in the Police cars when they went out on patrol, so that there would have been a quick armed response to anyone dropping from the sky. Then, the company I belonged to were sent to possibly defend the peninsula at Greenwich, the location now of the Millennium Dome. In 1940 there was a vast complex there owned by the South Metropolitan Gas Co, where it was reputed they made everything from Poison Gas to Epsom Salts. That in itself was unimportant, but the site itself was important, as whoever was in control there would control the traffic on the River Thames. The area around there was being very heavily bombed. One of our duties during the raids was, if incendiary fell on to the Gasometers, we had to clamber up and place sandbags over them, which was a pretty hairy experience.

After a spell there my company were drafted to Wakefield in Yorkshire, to join as reinforcements to the Third Battalion which had been badly mauled in France, and was in the process of being reformed. We were put into Civvy Billets, which was a great treat after being in barracks in London, having a decent bed to sleep in and home cooking; it did not last very long as the Battalion moved to the East Coast of Lincolnshire and Norfolk where we bivouacked, dug trenches and prepared positions to prevent the landing of enemy troops if they attempted the expected invasion. However, Hitler called off operation "Sea Lion", as it was codenamed, and we were ordered to stand down. There were stories at the time that some invasion barges had tried to land an invasion force somewhere along the East Coast and oil had been poured on to the sea and had been set alight. Rumour had it that burnt corpses had been washed ashore, but I never saw any myself.

We then had another change of duty. We were sent to where the aerodromes of the fighter planes operated from (viz: Biggin Hill and Henley) as the Battle of Britain raged on; the Germans had a ploy of following returning aircraft and shooting up the runway. An ingenious means of defence was sunken pillboxes which by the use of hydraulics rose from the ground and could be used to engage any incoming enemy. Eventually, the R.A.F. formed their own Defence Regiment and we went off to the Home Counties, mainly Surrey, to resume battle training. One location was Lingfield in Surrey where we were billeted in what was formerly racing stables, which was an ideal billet on the grounds that one was able, when off duty, to slip in and out surreptitiously without being caught.

Having a drink in the local pub one evening, I met a girl named Jessica, and after a few more meetings we began a relationship. I soon found out that she was married to a soldier and I should have ended it, but as it was wartime, one's morals were not as good as they ought to have been, and we spent as much time together as we could. It was wonderful whilst it lasted, but it all came to an end one night when I was with Jessica at her home, and she cried out that her husband and his father were approaching the front door. It transpired that they had found out she was having an affair with a Guardsman and they intended to give me a good going over. I scarpered out the back way and got clear. A couple of days afterwards the Padre of the mans unit came to see me and accused me of breaking up the marriage, and I got reprimanded by the Adjutant and was transferred to the Fifth Battalion, which was stationed in Yorkshire. A sad end to a romantic interlude.

The war had been going on for a couple of years now, and the situation was not looking very good for Britain. Italy, of course, had allied herself to Germany and now the Japanese had entered the conflict against us and the United States. The Japanese were defeating us in the Far East, and in the Middle East the Germans and Italians had us on the run. All the Army who were stationed in Britain could do was to carry on training hard and build up enough strength in manpower and armaments to be able one day to counter-attack the enemy abroad whenever and wherever possible and eventually mount an invasion on the mainland of Europe. Most of the training we did was in the north, over the bleak Yorkshire Moors. At Christmas in 1942, we were at a place called Louth in Lincolnshire, billeted in stables and barns on a farm. Some of my comrades who knew I had been a butcher persuaded me to kill and dress a turkey, which operation I duly carried out using my bayonet. It was a huge bird, about 20-30Ibs, and we boiled it and had it for Christmas dinner. It was not what you would call a gourmet meal!

In 1943 we moved to Scotland to go on manoeuvres in the highlands; at the time of course, we were unaware what our ultimate destination would be. The powers that be were of the opinion that that particular terrain was similar to that found in North Africa, which was where we were destined to invade. The first place we arrived at was Ayr, where we bivouacked on the racecourse there (we seemed to have had an affinity with horses!) From there we were sent on a scheme to the Isle of Arran which lies off the coast of Ayrshire, way across the Island and get picked up on the other side a few days later. It was in the middle of winter, we were split into pairs, were not given any rations and were told to live off the land. The idea of the exercise was how to survive in an hostile environment. My luck was in; on the second night we came across an isolated cottage which was occupied by an elderly couple who were frightened out of their lives when they saw us! But the best thing was, there was a middle aged woman who was staying there; she was the wife of a Naval Officer and apparently, she had come there to get away from Glasgow, which was being heavily bombed. Anyway she took a shine to me and that was that, enough said! I would not have minded staying another month or two there. My mate and I made our way to Brodick on the coast where we were to be picked up. There were some shops there and it did not seem that things were on rations. All commodities were supposed to be rationed in wartime Britain, but I was able to purchase several packets of tea and sugar which I sent home when we got back to Ayr, which was much appreciated by

Mother.

After a spell in Ayr we then moved to a mining village called Tarbolton, where we went into civvy billets which was a real treat, especially if the man of the house was on night shift! But after that the honeymoon period was over for we poor soldiers, and we were now due for real hardships. We embarked at Ayr on to a ship and steamed via the Sound of Bute to Loch Fyne and dropped anchor at Inveraray, where we stayed on board for several months staging amphibious landings and trekking over the Highlands and training in the art of combat with the Commandos at Fort William. This took place in the most appalling weather conditions - driving rain, snow, freezing nights - and it was worse than anything we were to experience overseas. Eventually we sailed out of the Loch via the River Clyde and disembarked at Perth, where we stayed a while in a carpet factory there, awaiting a Troopship to transport overseas. I went on embarkation leave from there and had a few days at home. My other sister, Joan and the man she married, Alec MacPheat, were both there. He was on war work in the area, at a small factory at St. Marychurch, turning out aluminium parts for aircraft. He had been invalided out of the army which was where Joan met him, when she was working for the N.A.A.F.I. My father was also working at that factory as a cleaner. Bloss and Tony, her son, were also there. Tony, who was just a small child then, can remember me coming home with all my equipment and weaponry. It was the last time I ever saw my mother.

Contributed originally by Peter R. Marchant (BBC WW2 People's War)

Don’t tell Adolf about the wonders of country living for a small city boy. Don’t tell Adolf about the exciting playgrounds of the bomb damaged houses. Don’t tell Adolf about the excitement of the search lights and the guns and don’t tell Adolf how he changed my early childhood into an adventure often frightening, but with vivid memories I recall to this day.

My very first ever memories are framed by the war. It must have been sometime in 1940 when I was almost four years old. Our family, my Mum and Dad and my older sister Thelma, were living in a Victorian row house in Clapham, London. This area has now become quite fashionable with house prices equal to my father’s life time income. Then, it was a working class neighborhood, clean and respectable, populated by postmen, mechanics and lorry driver tenants like my father. The only thing I can remember about the interior of the house was the Morrison shelter in the center of the bedroom. There I spent many weeks of isolation with a severe attack of the mumps in uncomprehending discomfort, picking at the grey paint of the cage unable to take anything more solid than my mother’s blancmange and barley water, her remedies for all known human ills. I’m sure my parents were grateful the authorities provided us with a combination bomb shelter, table and sick bed, although I wonder was anyone actually saved by this contraption? This was a time when one’s betters weren’t questioned; my family rarely doubted they must know what was best for us. For those who know only about more serious bomb protection the Morrison shelter consisted of a bed surrounded with stout wire mesh and a steel top on four corner legs about the right height for a table. The idea was to prevent the occupants from being crushed to death under falling masonry, a small sanctuary to wait in, listening for the scrape of shovels and praying to be rescued before the air ran out. In addition to the ugliness and awful paint its major flaw was the assumption that we would all be in bed when the house collapsed, a family so stunted by food rationing that we were able to sleep together comfortably in a double bed. Did Adolf realize the Morrison was part of the propaganda war designed to show the Germans that we English were just as viral as the master race; a people that only needed a tin bed as protection from their bombs?

As I got better I was allowed to play in the garden at the rear of the house. I remember it as long and narrow flanked on one side by the windows of a small factory making parachutes, or bully beef, or some other necessity for killing the enemy. The weather must have been hot as I recall the young women talking to me through open windows. They seemed happy in their factory routine and the pound or two a day they earned which was probably the best money they had ever made. Or were their smiles just for the rather shy little boy they gave the small pieces of chocolate and orange segments then as rare and sought after as black truffles? If there’s a page in the calendar that can marked as the beginning of my generally good relations with the opposite sex it’s probably spring 1940.

There are many more memories that come to me clearly but they are mixed in a jumble of time. It must have been after the serious bombing of London started in summer 1940 that my sister and I were evacuated. We were all caught up in a great sea of events and

if the choice for our parents was having us with them so we could all be reduced to rubble together or safe country life for their children, it was not difficult to decide which train to catch. An adult knows the terrors and uncertainty of the world and has worries beyond tomorrow but a small boy knows only the moment and thinks of an hour as an eternity if an ice cream is promised.

We were sent to live with a Mr. and Mrs. Daniels and their two sons on their small holding at Gidcott Cross, a junction of narrow country roads about six miles from the market town of Holsworthy in the county of Devon. The surrounding country was divided into small irregular fields on a plan lost in antiquity, surrounded by tall hedges topped with thick bushes and occasional trees.

Many evacuees have grim stories to tell and we were very lucky to be in the care of a loving couple who treated us like their own. The Daniels had a few acres near the house and some additional pasture rented nearby. On this they kept a few milk cows, all with pet names, Daisy, Sadie and Jessie, a pig or two and a muddy barnyard full of chickens. A pair of ducks stayed most of the year in a narrow rivulet that ran around the house. A female dog Sally, always ready for a rabbit hunt, followed us around everywhere when she was not ensuring a new supply of terriers. The farm house had, or rather has, as it seems little changed over the years, thick rough walls yearly whitewashed, four or five rooms in two stories under a thick thatched roof. The Daniel’s house was at the foot of gently sloping fields set back from the road with a pig barn on the left and the milking shed and hay storage on the right of the heavy slab stone front path.

Mr. Daniels was a member of the local Home Guard, a group of tough wiry men too old for immediate military service. There were no blunderbusses or pikes, but modern weapons were in short supply. Mr. Daniels had upgraded to a worn double barreled shot gun a deadly weapon in his hands as all the rabbits knew. At lane intersections old farm wagons loaded with rocks were ready to be pushed into a road block. One clever ruse was redirecting the road signs, a confused German being thought better than a lost one. Any one advancing down the road to Holsworthy would find them selves in Stibbs Cross with only one pub, a much less desirable place to take over. The home guard met regularly near our cottage for drill and comradeship. It was so popular that the institution lived on well after the war as a social club. These men knew every blade of grass for miles around and would have caused any German paratroopers much annoyance if Adolf the military genius had ordered landings in this remote corner of England.

When they were not repelling German invaders the Home Guard kept an eye on the Italians in the area. Up the road was the Big Farm, big because it had a barn large enough to house a half dozen trustee Italian prisoners of war working the land. Riding on farm wagons pulled by huge shire horses, as petrol was very scarce, they would stop outside our cottage on their way to the fields. They looked like old men to me though they were just young boys probably not yet 18, endlessly happy to be out of the war, captured by a humane enemy and ending up in this idyllic setting. They carved wooden whirligig toys with their pen knives for me and the nostalgic Italian songs they sang I can hear in my mind to this day.

It was a wonderland for we city kids with farm animals, the open country to explore and no shortages of food. The farm was in most ways self supporting, if you wanted a stew you shot a rabbit or two, or cut the throat of a chicken. I helped with the endless farm chores collecting eggs every day from the nest boxes, when the chickens were good enough to cooperate. Many chickens didn’t appreciate the conveniences we provided and made the job into an adventure searching the hedgerows for errant layers. No tinned or horrible dried food for us, everything was fresh as the vegetables pulled from the ground within sight of the front door. When we eventually returned to London my sister and I were noticeably well fed and quite fat, the battle for my waist line probably goes back that far!

Without modern conveniences it took most of the daylight hours to keep the house running and everybody was expected to pitch in. Another of my ‘helping’ jobs was to help fill the water barrel. With a small boy’s bucket and many trips I walked up the road a hundred feet, to the well hidden in a hedge tangled with wild roses, pushed the wooden cover aside and, after tapping on the surface to send the water spiders skimming out of the way, dipped in my bucket. This taught country ways very quickly and water became a precious commodity to be recycled for many uses until it was finally used to scrub down the flag stone floor. The water was heated in a large black iron kettle hung on a chain over a log fire in the inglenook fireplace the only source of heat in the house. Cooking had changed little over hundreds of years and savory stews and soups were made over the burning logs in large iron cauldrons. There was no electricity or gas in our cottage and finer cooking required Mrs. Daniels skillful fussing with a flimsy paraffin oven in the back room from where emerged a stream of delicious pasties, or covered pies, filled with a range of edibles that would have surprised even a Chinese cook. These pasties were brought out every meal covering the table with a smorgasbord of dishes from ham and egg, potato and wild berries, until finished. The men took them into the fields stuffed in their Home Guard haversacks and with a jug of local cider and after grueling days in the sun bringing in the harvest ate dinner sprawled against the hay stacks. The days ran with the cycle of the sun; the evenings were lit sporadically with a noisy pressured paraffin lantern and bedtimes were shadowy with the light of candles.

I remember my evacuation with the Daniels as an idyllic time although now I detect there must have been a feeling of abandonment and bewilderment long buried. One of my parent’s visits I didn’t recognize the lady with my father as my mother had just started wearing glasses. Later on, another visit, I wandered the lanes all day looking for them on a country walk they had taken and was tearfully relieved to find them sitting in a field eating sandwiches having no idea how upset I was at being left. Evacuation must have had a profound effect on many young children like me. My wife thinks that this experience is the cause of many of my strange ways and quirks of personality although I claim genius has its own rules.

My sister and I were returned to London after a couple of years in the country, the precise timing is vague in my memory. The aircraft bombing was much less now although the sirens still wailed for the occasional raid setting the guns booming on our local Clapham Common. I wish I still had my treasured collection of shrapnel from the antiaircraft shell bursts that rained down razor sharp fragments of torn steel and made being outside as dangerous as the bombing. These would be poignant reminders of this time so distant it feels like another life. Memories of my best friend Basil who always managed to find the pieces with serial numbers, the most coveted in our collection.

I recall one night the warning sirens sounded and the sky was lit by searchlight beams probing for the attackers. Within minutes the street was as bright as the sky, plastered with small oil filled fire bombs. They were everywhere causing small fires in the gardens and on the roofs of our street. One slid through the slates and wedged itself under the cooker of our upstairs neighbour, Mrs. Tapsfield. My father spent the night running up and down the stairs carrying buckets of dirt from the garden and spraying the cooked cooker with a stirrup pump. I can, even now 60 years later, see my mother next morning standing on a chair with a hat pin puncturing the hanging bladders of water filled ceiling paper from the flood upstairs. The fire bombs caused a lot of minor damage but they were all damped down and none of our neighbours lost more than a room or two. For many years after the sheet metal bomb fins would turn up when a new flower bed was dug deep. The trusty stirrup pump gathered dust in the coal cellar ready in case it was of need in another war in the new atomic age.

England was a very grey place with some rationing into the 50’s. For us kids Clapham was a wonderland of bomb damaged play houses and vacant rubble strewn lots. There were complete sides of buildings missing leaving the floors with wallpapered rooms precariously suspended. Bath tubs and staircases were stuck teetering to a wall with no apparent support stories up and the cellars were half filled with debris with only dusty tunnels for access. You can imagine the games these inspired for us boys. A special game was attacking and defending the half flooded abandoned concrete gun emplacements on Clapham Common and exploring the communal air raid shelters dug in the square. If only our parents had known!

How do you remember the events of a war time childhood? Memories are like a damaged film, occasional clear scenes separated by long stretches scratched and out of focus.

Through the often repeated stories distorted by their retelling; by today’s chance incidents that start a flow of thoughts to a half forgotten scene. Was it a page in a book or an E mail from a friend, who can tell the truth from imagination? I cannot be sure of the exact timing and the precise details of my experiences in WW2 they have been rounded off by time, and in this diary I have done my best. Although the accuracy may not be perfect and who can be sure in the valley of the shadow of memory, I hope to have conveyed the atmosphere of my experiences in these anecdotes.