High Explosive Bomb at Wyke Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Wyke Road, Bow, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, E3 2PA, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by The Stratford upon Avon Society (BBC WW2 People's War)

The Stratford upon Avon Society and Shakespeare Birthplace Trust

12a - Transcription of an interview that took place on the 18th February, 2005

Present:

Neville Usher Dr.Michael Coigley

Neville Usher: … you can tell, the tape recorder, it works but it’s noisy. And I am just transcribing one now were the problem is that the lady had got a canary with the loudest voice I have ever come across, it’s a job to hear.

Dr. Michael Coigley: Talking about birds, well I can tell you a lovely story about old Mrs. Tromans who was very old when she died in Alveston, and she had this budgerigar, and we went in to see her one evening and shut the door loudly, I didn’t hear what it said, but she said oh she said I am sorry, did you hear that, did you hear that? Oh I said no what? Oh she said the budgerigar, she said I got that she said when my dad died, after the war and it had been with him all the war in London, and if there’s ever a loud bang anywhere, it says “bugger old Hitler”, and if you slammed the door like we did, you could just hear this budgerigar saying “bugger old Hitler”.

Neville Usher: My grandparents had a friend who was the first female police officer in Birmingham, and one of my earliest memories is being taken to see this lady who lived in Yardley by the cemetery there and she had a parrot, and the parrot used to say “I’m Polly Miles, who the devil are you”?

Anyway, it’s Friday the 18th of February 2005, and we are at 6 The Fold, Payton Street, Stratford, it’s 11.15 and it’s very nice to be talking to Michael Coigley.

Could we just start very briefly with where you were born and how you came to Stratford and then move on to the war Mike?

Dr. Michael Coigley: Oh crikey. I was born in central London, the other side of the road from the Middlesex Hospital in a flat in a property which my father and grandfather later bought, and there’s a long story to that. And then we moved very quickly to Sidcup in Kent where my maternal grandfather was Borough Surveyor and Engineer, he had been head-hunted. He was a civil engineer of some repute really, he used to design …, he was very good at designing sewerage disposal systems. Well they got him in to oversee the first big East End slum overspill out of London to around Sidcup. And we had this lovely house which was an old medieval house with a Victorian extension on it, and he said better move because it is coming right behind you, so we moved out to Sevenoaks, I was born in London.

And then I was at Sevenoaks School, which is I think the first school to bring in the international baccalaureate, very progressive school and always very high up. The oldest …, one of the oldest grammar schools in the country, the only school mentioned by Shakespeare in one of his plays. Lord Sackville from Old House owned a lot of property round here of course, owned Halls Croft at one time, the Sackville’s, and in Henry VI part II, (shall I go on with this, because it’s very …?)

Neville Usher: Yes please, yes.

Dr. Michael Coigley: In Henry VI part II, when Jack Cave the Kentish rebel gets to Smithfield in London and is confronted by Lord Saye and Sele who now lives at

Broughton Court …, Broughton Castle near Banbury. Well Sele is a little place next to Sevenoaks in Kent and he took his …, it was a Norman title that he took the title Sele from Sele next to Sevenoaks and he and Sir William Sennard were the two founders of Sevenoaks School in 1432, and it’s the only school he has anything to do with, and Jack Cave before they behead him on stage says you are condemned for corrupting the youth of the realm in erecting a grammar school, so that has been researched and well is obviously Sevenoaks School,it was found out,it is the only school.

Anyhow, I was taking a scholarship to Cambridge called The Tankred Scholarship, King Tankred of Sicily was the Norman King of Sicily in 1065/66, and of course they went both ways the Normans didn’t they, they went to Sicily and England, William came here, went both ways. And he’d been worried, this Norman Tankred was English by now in the sixteenth century that scientists were becoming too specialized at a young age, this scholarship had to take in history, classics, something else, in order to read a science, so I never used it because the war came, and I didn’t want to spend the next 18 months studying medicine.

And I remained a medical student during the war because I was actually a “Bevin Boy” (do you know the Bevin Boys?)

Neville Usher: Yes

Dr. Michael Coigley: And the only way I could get out of going down the mines was to remain a medical student which I did so I was at St. Thomas’s during most of the war; we were evacuated of course down to Surrey, and then we came back to very difficult things at St. Thomas’s. And I then met …, I met Sylvia my wife whilst I was there, I then went in the army after I had been qualified for two years and went out east, thinking we were going to have a nice time but spent two years trekking through the jungle after the ruddy bandits.

Neville Usher: Oh dear, in Burma, or …?

Dr. Michael Coigley: No, Malaya, Malaya, it was after the war you see, it was ’48, the Malaya emergency started in June ’48. And then I came back and did a few jobs and wondered what to do, and then Scot Trick who was a partner - do you remember Scot Trick, old Trick? Well Scot Trick who was a partner in the Bridge House practice, the senior partners being Harold Girling, Dudley Marks and Scot Trick, Offley Evans and etc. And he had a very bad coronary on New Year’s day 1954 and for some reason, I can never know why and he wasn’t quite sure, the secretary of the medical school from St. Thomas’s rang me and said (because Dudley Marks was a St. Thomas’s man), and he was a local surgeon, he was a senior surgeon, South Warwickshire, one of the old GP surgeons you know, and he had rung the medical school saying do you know anybody who wants a job quick? So he rang me and said there’s a job going up there if you’re interested, and I said well I don’t know really, I wanted to be a cardiologist at the time, and I was working in the hospital you see, senior registrar in the hospital in Chichester, and Sylvia’s mother was dying of alchziemers just outside Leominster where they lived, Herefordshire, and we were going backwards and forwards and so I rang ‘em up, going up the next weekend, and came for the interview on Saturday morning with Harold Girling and Dudley Marks, and Offley was there, and out of interest and that was that, and the following Sunday Harold Girling rang me up and said when can you start? Well I had sort of dismissed it from my mind really and we had to think very deeply about this because I had this job, I had to get a release etc. from it, but with my mother in law being so ill, deep in the country, and Sylvia going backwards and forward all the while, so we decided if I could get released I would take it, although I could go back to the hospital you know after a couple of years, anyhow I never went back to the hospital because I liked it so much here, and it’s been great, so that’s how I got to Stratford.

Neville Usher: And what about the Second World War, what did you …?

Dr. Michael Coigley: Well I was in dad’s army of course, and my father who was auctioneer, chartered surveyor, estate agent etc. in Kensington in London (his business of course went), so he took a job doing war damage survey work covering over all the East End bombs and everything, and he’d been in the trenches in the ‘14/18 war of course my dad, and “The Lion” kept getting bombed, and so they moved, everybody was being evacuated, they moved further into London, they moved into Chislehurst, and at that moment I had got a place in medical school, and I well remember the interview I had for medical school because I went up with my father and I saw a very famous chap Thompson, Big Bill Thompson who was then at medical school a famous chap, and we went to see Chu Chinn Chow at the Palace Theatre that night, and there was a hell of an air raid, we weren’t allowed out of the theatre (we got out about three o’clock/four o’clock in the morning at the end), and being entertained by the cast marvellously all night you know, and got home to find there was a telegram to say that I had got a place in the medical school.

And neighbours at Chislehurst, and the Home Guard headquarters was next door to us actually at Chislehurst, and I was in that, but then the medical school were evacuated to Surrey, and it was a military hospital that had been built at Guildford, outside Guildford, and they took that over ‘cos Thomas’s was bombed quite badly, and about the only hospital really …, but they were after the Houses of Parliament of course which is the other side of the river, right opposite, and so there I was and I qualified at the end of ’46, and took my degree in March ’47.

But during that time you know, Chislehurst was right on the …, whenever I was at home I had to get up every night to firewatch on the roof and that sort of thing ‘cos you had got incendiaries all round you, you know, and funnily enough yesterday I went to see the Orpen, William Orpen exhibition at the Imperial War Museum, it is a brilliant exhibition and I was just walking out and there was a chap and his teenage son, and he can’t have been more than, I should think he was forty, something like that, they were looking at the V1 and the V2, doodlebug, and the V2 and I heard him say …, I just stopped to have a look and he said to his son, of course that was the V1 and that was the V2 big rocket, and he turned to me and he said “am I right”? He had diagnosed me brilliantly! Am I right? And I said yes you are absolutely right, and I can tell you about the very first V2 which dropped on this country, it dropped at Petts Wood and my mum was just doing the washing up in their top flat in Chislehurst and she got the cutlery, the crockery, she got the crockery together on the sink, on the drainer, and she took some of it to put in the cupboard along the wall and as she did that there was a hell of a bang and the window over the sink came straight past her and pretty well hit the wall, and that was the first; and nobody knew what it was of course. We had had the V1s of course, the put, put puts!

Neville Usher: But they couldn’t pick it up with radar or shoot it down, it was so fast?

Dr. Michael Coigley: No, a rocket. But I tell you a story about the V1s, because they had this ram jet engine, they went “put, put, put” they came on, when it cut out you knew it had gone somewhere, and they used to sort of hear the wind whistle when they came down, and I came off Home Guard duty early one morning, and I thought oh I just popped in home, took my uniform off though it’s not worth doing anything, I’ll go to bed, and went down to the station, caught an early train, went into the students’ club at St. Thomas’s, saw a chap called Dempster there, arrived at the same time (a very good fly half he was by the way, died about two years ago), and we said let’s have a game of snooker. So we went into the billiard room and we were having a …, and we heard put, put, put, we heard this V1 approaching, we looked out of the window and it was coming actually straight for us in the club. We looked at each other, we got under the billiard table and shook hands and nothing happened, nothing happened, we hard it whistle past, an air current took it up and it went along York Road and it dropped on a siding of Waterloo Station and that caused some trouble because it hit a tanker which had some phosphorous substance in it, took the top off a bus, killed a lot of people, and we all rushed over to casualty, and police came in and somebody had discovered this phosphorous liquid stuff in this tanker, and it’s a devil if you don’t get it off the skin, and it’s undetected you can see it, so we got the books down, and it’s very simple, you make a solution of copper sulphate like you used for bathing, wash it over it goes black, and you can see it, otherwise it goes on boring if you don’t.

But there were so many experiences during the war. I was on duty the Sunday morning in casualty that the doodlebug fell on the Guards Chapel, that was carnage that was terrible, and we had all the casualties in from that and I can see a Guards Sergeant Major, and funnily enough I served with The Guards out in Malaya later, and being lead up the ramp to casualty with a guardsman in his arms, all of them just covered in blood and god knows what and his face shattered, he couldn’t see and yet he had another guardsman in his arms, he was 6’2” or so the Sergeant Major, and another guardsman you know, I thought you know these chaps are marvellous.

[continued]

Contributed originally by peter (BBC WW2 People's War)

Setting the scene:

My Dad was the headmaster of a Junior Boys School, Attley Road, in East London, just round the corner from Bryant and Mays Match Factory.

I went to the local Infants and Junior School, "Redbridge" in Ilford, Essex

The transmission of news and public information was by the BBC Wireless, the Cinema News Reels and the National Newspapers. The whole impression, looking back, was of an extremely formal (and, as it later turned out, easily manipulated) information system.

Evacuation

The news had swung from the optimism of Munich to an increasingly pessimistic view. I sensed, even at my age of nine, that most people thought that the war with Germany would come and come soon. My reaction to all this and that of most of my compatriots was one of excitement tinged with some trepidation.

Every school in the area of greater London (and Manchester, Liverpool etc. I now know) had made plans to evacuate all children whose parents had agreed for them to so go. As my father was an Head Teacher it was decided that I with my mother as a helper would go with his school if and when the call came.

We started to prepare ourselves for what to me and thousands more children was to be the start of a great adventure. We had been issued with rectangular cardboard boxes containing our gas masks and these were mostly put into leatherette cases with a shoulder strap. We also each were to have an Haversack to hold a basic change of clothes, pyjamas, wash bag and so on.

During that late August 1939 we had a rehearsal for evacuation and every school met up in the playgrounds and were marched off to the nearest Underground Station. The next stage to one of the Main Line Stations was for the real thing only.

We each had a label firmly attached to a button-hole with our name, address and school written on. Each child had to know its group and the responsible teacher. This tryout was to prove its worth very soon.

The news was getting worse by the day. Germany then invaded Poland and it was obvious that the declaration of war was imminent.

At 11 am on Sunday the 3rd of September the Wireless announced that despite all efforts we were at war with Germany. It was, in a funny kind of way, an anticlimax.

My memory fails me as to the precise date of our evacuation. It was, I believe, a day or so before the war started, probably the 1st of September, no matter, the excitements, traumas and all those myriad experiences affecting literally millions of children and adults were about to start.

The call came. We repeated our rehearsal drill, arriving, in our case, by bus and train to Bow Road station and walking down Old Ford road to Attley Road Junior School. All the children that were coming, the teachers and helpers assembled in the play ground. Rolls were called, labels checked, haversacks and gas masks shouldered. We were off on the great adventure!

We "marched" off with great aplomb to waves and tears from fond parents who did not know when they would see their kids again, if ever.

The long snake of children and teachers arrived at Bow Road Underground Station and were shepherded down onto the platform where trains were ready and waiting.

Looking back, the organisation was fantastic. Remember, this was in the days before computers and automation! It was made possible by shear hard work and attention to detail. Tens of thousands of children were moved through the Capital transport system to the Main Line Stations in a matter of a few hours.

Our train arrived at Paddington by a somewhat roundabout route and we all disembarked making sure to stick together. We walked up to the platforms where again the groups of children were counted by their teachers. Inspectors were busily marshalling the various school groups onto awaiting trains.

We boarded our train together with several other schools. It was a dark red carriage, not, as I remember, the GWR colours, and settled ourselves down. The teachers were busy checking that nobody was missing and we then got down to eating whatever packed food we had brought with us. Many of the smaller children were beginning to miss their Mum's and the teachers and helpers had their work cut out to calm them down. Remember that most of these children had never been far from the street where they lived.

Eventually, the train got steam up and slowly moved out of the station. This would be the last time some of us would see home and London for a long time but, we were only kids and had no idea of what the future would hold. To us it was the great adventure.

The train ride seemed to go for ever! In fact we did not go that far, by mid-afternoon we arrived at Didcot.We disembarked and assembled in our groups in a wide open space at the side of the station where literally dozens of dark red Oxford buses were waiting, presumably for us.

It was at this point, according to my father, that the hitherto brilliant organisation broke down. A gaggle of Oxford Corporation Bus Inspectors descended on the assembled masses of adults and children and proceeded to embus everyone with complete disregard to School Groupings.

The buses went off in various directions ending up at village halls and the like around Oxford and what was then North Berkshire.

My father was by this time frantic that he had lost most of the children in his care (and some of the staff) and no-one seemed at all worried!

The story gets somewhat disjointed now as a combination of excitement and tiredness was rapidly replacing the adrenaline hitherto keeping this nine year old going.

Anyway, what can't be precisely remembered can be imagined! We, as mentioned, went off in this red bus to a destination unknown to all but the driver (and the inspector who wouldn't tell my Dad out of principle) - I'm sure, in retrospect, that this is when the expression "Little Hitler" was coined!!

On our bus were about fifty odd children and six or seven teachers and helpers. Most, but not all, were my dad's, but where were the rest of the two hundred or so kids he'd started out with? It was to take several days before that question was to be answered.

After some hour or, so two buses drew up together in a village and parked by a triangular green. There was a large Chestnut tree at one corner and a wooden building to one side. There was also a large crowd of people looking somewhat apprehensive.

We all picked up our haversacks and gas masks and got off the buses, marshalled by the teachers into groups and waited.

Ages of the children varied between seven and fourteen and naturally enough there were signs of incipient tears as we all wondered where we were going to end up. For me it wasn't so bad because I had Mum and Dad with me - most of them had never been separated from their families before.

A large man in a tweed suit, he turned out to be the Billeting Officer, seemed to be organising things and he kept calling out names and people stepped out from the crowd and picked a child out from our bunch. It closely resembled a cattle market!

My Father, naturally, was closely involved, monitoring the situation and trying to keep track of his charges while all this was going on.

Eventually, when it was virtually dark, everyone had been found homes in and around the village. Some brothers had been split up but, most of the kids were just glad to have somewhere to lay their heads.

While all this was happening we found out where we were; not that it meant much to me then. We were in a village called Cumnor situated in what was then North Berkshire and about four miles from Oxford.

At long last, after what seemed to me to be for ever, I was introduced to our benefactors who we were to be billeted with.They were a pleasant seeming couple of about middle age & we stayed with them for about 6 months before finding a cottage to rent.

The Village at war

It is difficult to include everything that happened during that period of my life in any precise order. Therefore, I have included the remembered instances and effects relating to the war.

The first effect was, undoubtedly, the upheaval in agriculture. Suddenly fields that had lain fallow ever since the last war were being ploughed up to grow crops. Farmers who had been struggling to make ends meet for years were actually encouraged and helped to buy new equipment to improve efficiency.

The war didn't really touch the village until the invasion of France and Dunkirk. That is, of course, not to say that wives and girl-friends weren't worried about their men folk serving in the forces.

Then, all of a sudden, you heard that someone was missing or, a POW. The war was suddenly brought home with a vengeance to everyone. Also, the news on the wireless and in the newspapers was very bad, although usually less so than the reality.

One of the village girls had a boy-friend who was Canadian. He had come over to Britain to volunteer and was in the RAF. He was a rear gunner in a Wellington bomber and was shot down over Germany during 1942.

For a long time there was no news of him and then Zena, her name was, heard that he was a POW. At the end of the war he returned looking under-weight but, happy and there was a big party to celebrate his return and where they got engaged! a truly happy ending.

Another memory, this time not a happy one, was the son of some friends, who was a Pilot in the Fleet Air Arm was shot down during the early part of the war and killed in action.

There was a Polish Bomber Squadron based at Abingdon and they were a mad lot and frequented a pub near to Frilford golf club called "The Dog House".

As the war wore on so the aircraft changed. Whitley and Wellingtons were replaced by Stirling's and Halifax's. finally, the main heavy bomber was the Lancaster. These used to drone over us from Abingdon and other local airfields night after night.

We also started to see a lot of Dakota's often towing Horsa gliders. In fact, several gliders came down nearby during one training exercise and one hit some power cables, luckily without major injuries to the crew.

More and more of the adult male and female villagers had disappeared into the forces and more and more replacements were needed to work the farms.

The result of all this was to put at a premium such labour as was available. This meant Land Army girls, POW's and me and my friends!

Various Army units appeared from time to time on exercises and the like.

It sounds strange now but, remember that everyone was travelling around at night with the merest glimmer of a light. Army lorries just had a small light shining on the white painted differential casing as a guide to the one behind. Cars had covers over their head-lights with two or, three small slits to let out some light.

Then there was the arrival of the Americans - I believe it would have been during 1942 that they were first sighted. They were so different to our troops - their uniforms were so much smarter and their accents were very strange to us then.

They established a tented camp just up the road from the Greyhound at Besselsleigh and naturally it became their local. This was viewed with mixed feelings by the locals as beer was in short supply and the Yanks were drinking most of it!

Their tents were like nothing we had ever seen then - They were square and big enough to stand up in without hitting the roof. They were each fitted up with a stove. Nothing at all like the British Army "Bell tents".

We all got used to seeing Jeeps and other strange vehicles on our roads, they in turn, got used to our little winding lanes and driving on the wrong side.

The Americans were very keen to get on with the locals and when invited to someone's home would usually bring all sorts of goodies such as tinned food, Nylon's for the girls and sweets for the kids. They knew that the villagers didn't have much of anything to spare at that time.

A British Tank Squadron came into the village at one time. They were on the inevitable exercise and were parked down near Bablockhythe, in the fields. We boys went down to see them and found about four or, five Cromwell (I think that was their name) Tanks parked with their crews brewing up. Naturally, the sight of all that hardware was exciting to us and we were allowed up and into the cockpit of one.

During the build up for the D day landings there were convoys going through the village day and night. There was every sort of vehicle you could possibly think of - Lorries, Troop Carriers, Bren Gun Carriers, Tanks of all shapes and sizes, Self-propelled Guns, Despatch riders and MP's to control and direct the traffic.

This almost continuous stream continued for what must have been a fortnight before it gradually quietened down to something approaching normality.

Naturally, during this time and whenever I was home from school I would walk up to the corner just below the War Memorial and watch these convoys with great interest and excitement.

There were troops of every nationality including French, Polish, Czech, Dutch, Canadians, Anzacs, Americans and so on. Obviously, the build up for the second front was beginning and something big would happen before too long!

Just before all this activity we had seen dumps of what seemed to be ammunition along local country roads and this was further evidence that the big day was getting close.

People's morale was starting to improve by this time. It had never been broken but, for three years the news had been mostly bad or, at the very least, not good and people's resistance had begun to wane a little.

North Africa had been a great victory and this coupled with the nightly bombing raids over Germany and the day raids by the Americans as well, really cheered people up and convinced them that we had turned the corner.

Everyone, including us teenager's used to sit with our ears glued to the wireless when there was a news bulletin.

People, during that wartime period in their lives, were much closer to each other than they had ever been.

Back to 1944 - The build up of men and materials continued and there was a constant stream through the village. Then a period of calm followed for a week or, so. And then came the news of the D Day landings - we all sat with our ears glued to the wireless whenever we could. For the first few days the news was fairly sparse and we didn't really know if the invasion was going to work.

After a week or, so the news began to be more positive and our hopes were raised. There were set backs and of course, there were casualties but, we were getting closer to the end of the war.

Then one Autumn morning in very misty conditions we heard lots of aircraft overhead. Through the patches of hazy sky we could discern dozens of Dakota's and the like with Gliders in tow. A few hours later they were to return with their gliders still hooked on.

Wherever they had been going to drop their tows must have been covered in the fog that had persisted most of that day over us. The result of this was gliders being released all over the place as the Dakotas prepared for landing.

A day or, so later the same "exercise" was repeated and this time the planes returned without their gliders. The battle of Arnhem had begun.

So the war continued for several months but, one could sense that the end was drawing ever closer.

The war in the Far East was to continue for several more months but, at last, the main enemy had been defeated.

How did all this affect us? In all sorts of ways - there were preparations for a General Election. The soldiers began to come home and there were frequent welcome home parties.

Food was still on ration as was petrol and clothes. So, there wasn't any sudden improvement to the rather dreary existence we had all got used to. In fact, it was a bit of an anticlimax. One of the few nice things to happen in that immediate post-war time was the return of Oranges and Bananas to the shops. We hadn't seen these for six whole years!

Basically, The United Kingdom was worn-out and broke by the war's end and to a great extent so were it's people. Our former enemies were helped by the USA to rebuild their countries and industries as also were France and the Lowlands countries but, we had to try to help ourselves for no-one else was going to.

Peter Nurse 1994

Biddulph

Contributed originally by msbellvue (BBC WW2 People's War)

I was 4 years old when the big day came, September 3rd. 1939.

It took a while before the war started to affect us. It must have been sometime in 1940 that I first remember being woken by my old mum bless her, I remember it was so dark and very cold and she would never, never wake us till the buggers where right overhead.

This was West Ham, deep in the East End of London, with a railway yard, 2 chemical factories and a pumping station at the back of us and right in the middle was No.6 Pond Road.

Before the balloon went up some men came and dug a big hole in our tiny back yard and I saw what is now known as an Anderson shelter, it had 2 long benches inside and this was where we were going to spend many a long night.

My dad had died when I was a baby so my mum, sister and myself found things pretty hard. My mum worked shift Work in one of the chemical factories called Berks.

My sister had been evacuated to Newbury in Berkshire, so when mum was doing her shifts I would be farmed out to different neighbors.

We lived next door to a bakery which was owned by 2 brothers and these 2 men used to be in our shelter and had made themselves at home before we were able to get there, my mother did not like the situation one bit.

My mates and I would scour the streets in the morning after a raid looking for spent cases and pieces of shrapnel, sometimes this was still warm and the shell cases were great for swapping with your mates.

As the war went on us kids became used to dog fights in the sky, planes leaving vapor trails and weaving in and out with there guns blazing it was very exciting to us.

Many, many bombs fell in and around West Ham, one of my sister’s friends was killed during a bombing raid and many of our local shops were also flattened. A school, which was used as a fire station received a direct hit and many firemen were killed.

One of the most amazing night I remember was of being hauled out of bed, taken to the shelter, we were in there all night, the noise was incredible, all we had at the entrance to the shelter was a piece of wood about a yard square and so while all this was going on I peeped out and the picture I saw has stayed with me as though it was yesterday. The sky was alight with color, searchlights were lighting the sky, fighter planes weaving about with there machine guns blazing, the planes were very low and all the time you could hear the loud bangs from the bombs, that picture will stay with me forever.

Next morning not a window was left in our house, our street was completely wrecked, there was slates missing from the roofs and none of the house had windows. There were police everywhere, I remember the street being roped off, my mum was inside collecting things together, then I don’t remember how we got there but we ended up in Mill Hill. We stayed with a lovely family and I remember being given a box of lead soldiers and this was one of the best gifts I was given as a child. I can’t remember how long we stayed with these people but when we got home our house was clean, windows, doors and roofs were as new.

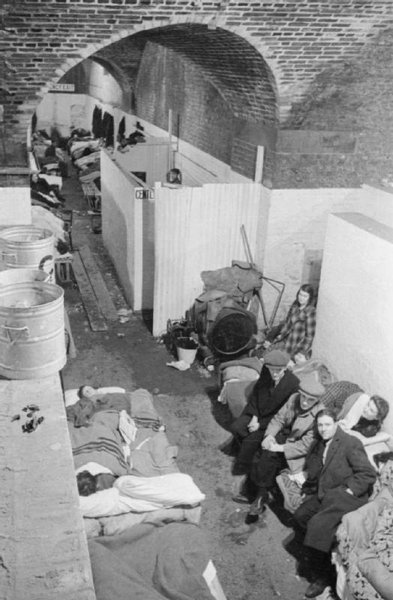

As the days went by and the bombing got worse we had to go to these big underground shelters where there were rows of bunk beds, these were in rows and you were sleeping next to people you had never seen before. There were crowds of us every night walking to the shelters with our blankets, some even took mattresses with them.

You got hardly any sleep and you didn’t know if your house would be there when you got back in the morning. Mums and Dads still had to go to work the next day How they did it I will never know. Could the young people of today do it? I don’t think so, do you?

One day the YANKS came to Pond Road, now the only Americans we knew were in the films so obviously to us kids back home in America they had all been either cowboys or some sort of gangsters like James Cagney.

Where the houses had once stood they started to put up prefabs, they gave us chocolate and gum and we looked at these tanned men in with our mouths open we found them unbelievable. They gave us their time and would stand and talk to us in a way that we were not used to and to us we felt they were all like the film stars we saw at the cinema, they were all so nice and nothing seemed to much trouble for them.

Not far away from where I lived was Carpenters Road, which had lot of factories which had been bombed out and the rubbish had been cleared and a prisoner of war camp had been built there, in it the prisoners were all Italians, they all wore dark battledress and on the back was either a large yellow diamond or circle. We would often see them walking about, we never spoke to them, but we would stare at them till they were out of site.

Sometimes we would see these prisoners with English girls, now this did not mean a lot to us children, but they would be told off by some of the mum’s and the older men as they were the enemy.

One time my girl friend came to our house crying and said her sister’s boyfriend had been killed in the war. I remember everyone just being so quiet. After that whenever we saw her sister, whose name was Vera, she was always alone.

Where my sister was evacuated was quite a nice place, we went to see her once. The house she lived in was opposite a huge park, once a German plane shot at her and her friends as they played in the park luckily he missed and nobody was hurt. Another time a German plane crashed in the park and my sister said they took the pilot away.

As the months wore on more and more parts of West Ham disappeared, whole rows of houses would be there one day and gone the next. In a part of West Ham there was a part you could walk from Stratford to Becton dumps, this long walk was called the “Sewers Bank” it is quite hard to describe what it looked like because I have never seen anything like it since. If you can imagine a really high grass covered bank at leasts30ft. or more high and under this ran a huge sewer pipe about 6ft. in diameter, it carried sewage and went over bridges which were over roads and rivers and went on for miles and miles. One day there was a mighty explosion and a V2 rocket had hit the side of the bank, lots of houses went in the blast and the smell was unbelievable.

You often hear Londoners say, “the Germans bombed our chip shop” well in our case it was true. I was in a neighbors having some dinner, I will never forget, it was stew, when BANG, the ceiling came down in my dinner, dust and plaster everywhere. A crowd had started to gather at the top of Stevens Road where there was a very large pub called “The Lord Gough” this had disappeared along with the small cinema and sweet shop which were next door. Opposite was “Eileens” the fish and chip shop, the front had been blown in and Eileen was badly injured and her face was permanently scarred which was very sad as she was only young and quite pretty,

The Doodlebugs came next and they were scary because you heard them and saw them but when the engine cut out they glided in silence so where they landed was in Gods hands.

The East end spirit saw many people through and we had many street parties, how the mums put food on these party tables must have been quite a feat as it was hard enough in the best of times, but they did it. Out would be brought a piano from someone’s house and a good time was had by all.

When the bombing eased up and things got easier my sister came home, it was very strange, I think my mum stopped doing shift work then and we didn’t use the shelter so much.

The Americans finished building the prefabs and moved away, those prefabs were in use for many years after the war.

I suppose if I am honest we kids quite enjoyed a lot of the war as it was like an adventure, and we didn’t see it the way adults did, to see planes fighting in the sky was so exciting and collecting bits of shrapnel and shell casings was like toys to us as we didn’t have a lot in those days..

I have tried to remember the parts that someone may find interesting of a small boys war.

Contributed originally by Billericay Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

6

We went to a school on Blackstock Hill while Mum continued to do her job at the Air Ministry. In the school holidays we were left completely to do whatever we like all day and having few toys and nothing creative to do, we inevitably got into mischief. Our main pastime was to go down the hill to Finsbury Park underground station, where for a small amount we bought a ticket and spent the day travelling around the London underground, finding out which stations hard the longest escalators to play on. The ticket inspector invariably saw us and chased us from station to station, while we nimbly jumped from carriage to carriage. The night air raid still continued and the sirens and guns firing made it very difficult to sleep. By summer, most of the children in school looked pale and tired. The schools country holiday find organisers did their best to send most of the children away for a short holiday and we were asked if we would like a week in Devon. Mum, glad to be relieved of us, was quick to accept. The week stretched to a fortnight and the to three weeks. Finally, Mum asked Mrs Clapp, the young naval wife with whom we were staying, if we could stay on a evacuees. Hilda Clapp was lonely living in her small cottage with only her one-year-old daughter for company. Not knowing when or if her husband would return, she agreed that we could stay.

Honiton is a pleasant little town famous for its lace making. It is surrounded by delightfully undulating country, where daffodils grow wild and profusely in the hedges every spring. I was glad to be in the country once again but hurt inside knowing full well that our mother no longer wanted us. Letters became less and less fequently and Hilda, after one prolonged spell without news, began to fear that she might have been killed in the bombing. All this worry was telling on me and my behaviour deteriorated greatly. Hilda began to find me more and more difficult to manage.

She had an auntie called Ivy who lived three miles away in the tiny hamlet of Coombe Raleigh and frequently sent me to stay with her at weekends just to give herself some relief. At least a letter arrived saying that Mum was all right but had moved to Bow.

By now I was ten and as the allied troops began to collect in preparation for the D-Day landings, large camps of American soldiers accumulated around the town. Back in London, Bill Daycott was recalled to his regiment, also in preparation for the landing in which he was subsequently to die. At Easter, Mum came, supposedly to see us. It was nine months since we had seen her and she had four whle days to spend with us but coming to Honiton on the train she met an American soldier called Steve, who was stationed near us and apart form meal times, in all those four days we hardly saw Mum at all. The town's tongue waggers had a field day discussing her behaviour and when she returned we were left to listen to it and feel ashamed.

7

This latest rejection resulted in a further deterioration in my behaviour and by mid-summer, Hilda could stand me no longer and home she said we would have to go. We sat on the tiny platform, waiting for the train to come in, while Aunt Ivy begged Hilda to keep us. ('You'll never forgive yourself if they get killed in the bombing,' she said). But Hilda was quite unmoved. So back to Bow.

Bow is what local planner call a twilight zone; I can't imagine why. The thoughts that twilight conjure up for me are of pleasant summer evenings, getting dusky, with a few stars just beginning to appear. Something beautiful, in fact, and there is absolutely nothing beautiful about Bow. Dirty streets made up of row after row of bay-fronted terraced houses, all identical and all with outside toilets and no bathrooms. If you wanted to keep yourself clean, it was a toss up between a quick wash down in the scullery, with the gas stove to keep warm, or a trip to the local public baths, where for seven pence second class or a shilling first class, after a two hour wait in the queue, you could have about eight inches of water and a half hour of privacy. We paid seven pence and took our place like second class citizens in the queue, while our more affluent friends paid a shilling to wash their supposedly first class body in the cubicle next door. Even this luxury was interrupted at intervals by the aged attendant calling out, 'Hurry up in there number three.'

We lived in one of these terraced houses without any electricity and went to school across the road in Olga Street. Few of the houses had any windows left in them by now and workmen were kept busy going round filling the window frames with brown paper-backed canvas. One enterprising schoolteacher obtained a roll of this material and, with the paper backing removed, the canvas was ideal for teaching us to do cross stitch embroidery as we sat in the air raid shelter.

School had practically come to s standstill due to lack of pencils and paper. One day, one of the boys in the school was blown to smithereens while fishing on the banks of the canal near Victoria Park. We took a collection for some flowers and the whole school stood outside to see the remaining pieces of Boy Franklin depart. But such is the resilience of youth that the very crater of left by the bomb that had killed our playmate now became our chief source of entertainment. We borrowed old bicycles and starting from the centre of the crater, we rode round and round, faster and faster, till we reached the perimeter at an angle of 90% like rider on the wall of death at the fair ground.

One night we went to bed surrounded by buckets and bowls and basin, to catch the drips from the far from leak-proof roof to be awakened by the most almighty BANG. The whole house seemed to rise in the air for a few seconds and come down again. There was a hole blown through the bedroom wall and from the window frame we could see flames coming from somewhere.

For a moment, we were too shocked to move. The slowly as the shock wore off, I heard Mum's voice trembling with fright say, 'Oh my gawd, we've bin hit.'

8

A few seconds more and then we began to move. We felt ourselves and found that miraculously we were all unharmed. We fumbled out way downstairs and out into the street. Other people were appearing from their houses too and we called to one another, 'Where's the hit?' Someone said, 'It's round the corner in Antill Road,' and we all began to run in that direction. The air was full of dust from the rubble.

As we turned the corner, an old man dressed only in his shirt, came wondering along the road, with his arms outstretched in front of him, like someone sleepwalking. He was completely dazed and was muttering to himself. Someone took him by the hand and said, 'Come on Dad, you're going to be all right.'

The railway bridge had completely disappeared. So had the chemist's shop next door to it; but in what remained of the stockroom behind it, a large carton of sanitary towels stood perched at a crazy angle, with it's contents slowly falling out like snowflakes down on the debris. The off licence shop on the opposite corner was also gone and when they found the body of Mr Rodgers the proprietor both his legs had been blown clean off.

The police arrived and immediately cordoned off the whole area. While rescue workers searched for more survivors, people stood around in little groups, questioning each other as to the cause of all this damage. Some thought it had been a landmine. Slowly, bits of information revealed that it was in fact the first of the V.I guided missiles. But with the humour born of hardness, which only cockneys possess, they had already nicknamed it the Doodlebug.

Doodlebugs arrived frequently and we got used to listening to all aeroplanes to see if their engines cut out. If it did, we ran for cover and counted to fifteen while waiting for the bang. If you heard the bang, we knew you were one of the lucky ones; you were still alive. But as if this was not enough, the Germans had more to offer; now the really big rockets began to arrive. In the early days of the blitz, people had got used to one or two houses being demolished and with the coming of Doodlebugs we got used to seeing whole streets disappear. But no one was prepared for the destruction of whole areas that these rockets caused.

The school authorities went on a positive campaign for the evacuation of all the children from the East End and, once again, off my sister and I went. No one knew how far the rockets would be able to reach so it was decided we must go as far away as possible. Our train went until it could go no further and stopped at the last station in Penzance in Cornwall.

Penzance is a charming little town which has a fine harbour and a beautiful botanical garden where tropical plants flourish in this area's mild climate. There are marvellous views of St. Michael's Mount, a small island in the bay. What a contrast from the London we had just left behind. All the houses actually had windows.

9

We were put into a bus and driven around the town, stopping at every street, while women came out of ther houses and looked us over and said, 'I'll have that one' or,'I'll take two,' as if we were inanimate objects. We went to a tiny old spinster called Miss Brett. Miss Brett had spent all her life as a governess in France and she was very strict with us. As we had been used to practically running wild in London, we did not appreciate this. She locked me in the bedroom for a whole day because I did not eact my greens. I wrote complaining to me mother but after I had gone to school, Miss Brett openend my letter and read it. Se was furious with me and that Saturday found us back at the billeting office. Evacuee was becoming almost a dirty word and not many people were willing to take them in. I knew it would be difficult to find somewhere else for us.

But somewhere was found and now we went to the home of Mr and Mrs Bear. They had two children of their own, a boy and a girl and one other boy called Jimmy who was the son of an officer in the army. This boy was an unmitigated snob, who considered himself to be superior to us in every way because, as he never ceased to tell us, he was a private evacuee and not a government sponsored one. We had not been here long before Mr Bear, a fat, lascivious man, began to take an interest in my sister, who was fourteen and fast developing into a young lady. Mrs Bear was quick to notice this and with the excuse that she was sick, took us back once again to the billeting office. I can’t think why they didn't put up a couple of camp beds for us there, it would have made life so much simpler for them.

Next we went to the home of Mrs Nesbitt. She lived in a small house in the centre of town, with her mother and son and daughter. Her husband was a prisoner of war in Germany and she worked as a newspaper roundswoman. Every day we had all the daily newspapers first and plotted the advances made by the Allied Forces in Europe to see whether Stalag 23 was liberated. At Christmas, Sis was fourteen and left school and returned to London to start work as the bombing had now ceased. So our family was broken down once again, my last emotional stabliser was gone and I was alone. I was very small and skinny for my age and without Sis to defend me, Robbie Nesbitt the fat, twelve stone son of the house took great delight in giving me a good thumping every time we were left alone in the house.

The bombing of London had now ceased altogether and many of the evacuees' parents sent for them to go home. Finally the war was declared over. Six weeks later U was still there; no one had sent for me. Mr Nesbitt arrived home looking white and thin. Then one day a rumour went round the school, we, the remaining refugees were going home next week. The excitement was terrific as the train pulled out of the station. Children ran up and down the corridors shouting joyfully, 'We're going home, we're going home.' But home is where you are loved and where you belong and where did I, the girl who five years earlier had left London plump and happy and now returned thin and bitter within belong? After attending eight different schools and having lived in thirteen different homes, with no father and a mother who no longer cared. The only truthful answer was nowhere. But like Scarlet O'Hara in 'Gone With The Wind', I learnt to say, 'Tomorrow is another day.' But that is another story.

Contributed originally by jasstuart (BBC WW2 People's War)

All very romantic. We think of sleep in a comfy bed, with spotless sheets, a plump pillow and a coverlet; or perhaps a Duvet. Forget it! For those who have the mileage and are able to remember the war years, read on. For those that don’t, listen to your Granddad.

We were Territorial Army lads, just returned from our yearly Camp on Beaulieu Heath, in Hampshire.

Under canvas of course and lying on the ‘good earth’, to sleep.

We lads of the 10th Battalion, Tower Hamlet Rifles; gathered together from the East End of London, in the Borough known as ‘The Tower Hamlets’.

We were ‘called up’ on the 1st September 1939. We were fully equipped, therefore we were told to take our rifles home and not to hand them back to the Armoury. We reported for duty the next day, when our ‘call up’ papers arrived by post.

Having said tearful farewells to Mums and Sweethearts; we were marched out of the Drill Hall on Tredegar Road Bow and on to Bow Road, ‘then right wheel’ into Cooper’s Company School.

We were about four hundred yards away from where we started, where our loved ones had just waved us goodbye. We were there for two whole months, sleeping in our army issue of three, ‘horse’ blankets, on the Parquet Floor.

Then we were taken to Swindon, to sleep on the dance floor of the Co-op Hall. We now had three new ‘horse type’ blankets each. They had to be folded with box-like corners and laid out neatly with knife, fork, spoon, housewife and mess-tin. Everything else, stowed away out of sight behind our kit bags.

Our webbing equipment, with bayonet and water bottle attached, spread neatly over the blankets, and army greatcoats, (if you had one), folded as per ‘regulation’, according to the Sergeant. Many of us still had Busmen’s Overcoats! Then a move to another part of the town; there to sleep on the concrete floor of a High Street garage.

Months rolled by, and we were training, training all the time, in the fine arts of a mechanised army, though sadly, we did not yet have our vehicles. We were ‘fit as fiddles’ and ‘straining at the leash’ to have a go at Hitler and his mates. But did we? No, We were sent to guard the Docks and ships on the Thames in the East End of London, and sleeping rough, among sacks of produce like raw coffee beans, along with the rodents who lived there. A few spies were captured, so we were told! We guarded the Dry Docks. Dickey Seewright fell in, fortunately there was still about ten feet of water, but a long drop.

Being in full equipment, helmet, pack, Bayonet and Rifle, plus Ammo Boots, he rolled over and over. Counter balanced, you see? We made Dickey as comfortable as we could on some dry sacking, gave him a good rub down, and then returned to our duties. Between helping the police evict unwelcome people off ships, and patrolling the Docks, we got our heads down, sometimes.

We spent most of 1940 around the Dock-land, sometimes assisting, where we could, with fire fighting.

Now we were under canvas on Hampstead Heath. At least with dry ground to sleep on, in bell-tents that had seen previous wars. And sleep? That was a laugh. Impossible with anti-aircraft guns banging away night and day, close to our Company Line’s, trying to bring down German Bombers.

We were then moved to Dunstable Bedfordshire. At the foot of a hill on Dunstable Downs, a windmill became the home for about twenty-five of us. The rest of A Company, now designated as part of the 10th Battalion the Rifle Brigade: Sixth Armoured Division: were scattered in derelict houses in the neighbourhood. Talk about ‘wherever I lay my head then that’s my home!’

During 1941 we received our vehicles. Now we charged around the country, trying to kid Hitler into thinking that we had more troops than he thought we had, and more Armoured Divisions to call on

We travelled by day and night, North, South, East and West, all over the country; with short rest periods in between, mostly when supplies and petrol were brought up. One spell of about three months, we slept under the July Stands, on the Newmarket racecourse. It was a concrete floor!

The MO’s Surgery was a stable. Most fitting we thought, for to us he seemed more like Vet.

Then we travelled to Scotland; once more under canvas, in bell-tents, leaking at the seams in the pouring ran and Scots Mist, that seemed to go on forever. We were camped by the side of a river, known to overflow its banks. Everywhere was mud. The nearest town was Stewerton in Ayrshire,

Whose people were kind to us, in spite of the mud we took with us on our infrequent visits.

At the camp we were issued with a rubber ground sheet each, which kept the blankets out of the mud;

providing you didn’t roll over in a troubled sleep. Now I was a Corporal with two stripes. Now when you are a rifleman, you have only have to worry about yourself; but as a Section Leader you have seven children to worry about. ‘See that they shave, are fed and watered, kept clean and dry, with untroubled sleep’. That’s a laugh, up to our eyebrows in mud! So we trained and trained. This time as a proper Scout Platoon in our Bren Gun Carriers, the Motor Platoons in their 15 hundred weight vehicles. All very mobile and ready to face the enemy; but the training went on until the day we were ordered to ‘up sticks’ and move out. It was now November 1942.

We sailed away on the Langibby Castle, sailing down the Clyde on a ship well loaded with troops, tanks, and all kinds of vehicles and equipment for war.

We sailed round and round in the Atlantic for a couple of days, until many other ships joined us to make up the convoy. We rolled around in the rough sea, but I was happy, for I was now a Lance Sergeant, which entitled me to share a cabin and have a bunk. It was heaven to lay where it was comfortable, on a soft surface and without draughts. We made our way steadily towards the Mediterranean and the North African Coast. But not for long, we were passing the twinkling lights of Tangiers, at dead of night, when a ‘U Boat Wolf Pack’ attacked the convoy. We copped a torpedo on the port side bow, making a hole above and below the water line that two double-deck buses could have driven through. Around us, ships were burning and exploding Water tight doors were closed, which gave us the chance to limp into Gibraltar, though the ship as well down at the bows.

At Gibraltar, we transferred on to the Lansteffan, another Castle Line ship. It was already pretty well loaded, though it still made room for a couple of thousand more troops. Our transport would have to catch us up later. We were meant to land at Algiers, it as under constant bombing raids and ‘U Boat’ attacks. The harbour in the Bay was ablaze. We finally landed at Bone; where our temporary abode was a deserted hospital, with arms and legs crammed into dustbins. We lay where we were put; on a cold but beautiful marble floor, with lovely blue tiles up the walls; though not appreciated at the time.

When our vehicles finally arrived, we set off towards the ‘war zone’ to chase the Germans out of Tunisia! Not that easy!

So now as a Lance Sergeant, I commanded three Bren Gun Carriers, three men to each Carrier, including me, as part of the Scout Platoon. As soon as we hit the area, we were in action. Skirmishing by day, foot patrolling by night. No rest, hardly any sleep, no time to use our new can openers. Though our spoons and mouths were ready to sample McConnickies solidified soup; eaten cold, straight from the can, as all our meals were. ‘I mean, come on!’ Do you think the front line Tommy had someone to cook for him? No chance! After a few days we managed to wedge in a bit of eating, a bit of resting here and there, and always a mug of tea at the first chance. Quickly brewed on a cut down petrol can filled with sand and fuelled with petrol. Quickly doused with a handful of sand, and carried, swinging

from the back of the Carrier. ‘Luxury!’

Our rations were packed in ‘three man packs’ to last three men three days. Ideal for a carrier crew.

It was full of assorted tins of food; all very plain and basic, after all there was a war on. Often we would get a tin of fifty fags to share between us, and a slab of dark chocolate sometimes, plus a packet of ‘paving slab hard’ dry biscuits. Of course, if supplies couldn’t get through to us, things had to stretch a little, but petrol was the chief need for the vehicles.

Naturally, we could usually find something to grumble about, but it didn’t do any harm and it gave vent to our frustrations. We were nipping about from one part of the battle zone to another. Being Mechanized Infantry, that was part of our job; filling in gaps, holding the line, patrols, patrols, patrols,

out there in the blue yonder! With so much driving, my driver Dusty Miller, could get very tired, so we took it in turns. With me at the controls, ahead in the dark, just catching the moonlight was a silvery concrete structure, like the model on a wedding cake. It was a bridge over a deep Wadi. That was how it looked as we approached. And then it was behind me. I too had fallen asleep, and dropped off! Just for a moment. Had we gone through that parapet, it would have been a longer drop, and probably out of this world. I didn’t tell the others, it might have worried them, though I doubt it.

Then the rains came. Troops and Vehicles of all kinds were bogged down in the clinging mud.

Wheels couldn’t turn and tracks had no grip. It was the same for Jerry.

On the outskirts of Bou Arada we dug two-man slit trenches, facing across the cold terrain towards the enemy positions at Le Keff. From those trenches, we were expected to rebuff any enemy infantry attack; though in the soaking wet, up to our ankles in mud we had little heart for it.

We splashed across that open ground on foot patrols, at night. Jerry did too, and often sent up Very Lights. We were a patrol of six men, walking on a compass bearing, in the dark. We had ‘hit the deck’

as a light burst above us. We waited for it to burn out. Out of the darkness a figure loomed. “That you Sarge?” he enquired casually. With the safety catch forward on my automatic, how I refrained from squeezing the trigger, I will never know. It was Chinner Halsey, our ‘end man’. His simple explanation

for wandering, was, ‘he just wanted to go to the Lav’. I saved my swearwords until next morning, then I let him have them good and proper! Nights in the slit trenches taught us how to sleep, standing up.

Just light sleep, you understand? Then your knees gave way and conveniently woke you up.

Once the ground was suitable to allow tanks and vehicles to move. We, as a Battalion, found ourselves once again, ‘in the thick of it’. It was at the end of January 1943,that our Platoon Commander lost his life. The Battalion was spread out over a large area and receiving supplies. Lieutenant Toms had just handed out the mail to his Section Leaders. We were walking back to our Carriers, when a lone bomber made a direct hit. We were all thrown about by the impact, and Lt Toms and the Platoon Sergeant, were hit. As often happens ‘in the field of battle’, with myself as senior, I jumped the equivalent of two ranks. Bypassing the rank of Platoon Sergeant and taking on the Platoon Commander’s job.

Not that I expressed my thoughts, though I did think, ‘Aye, aye, an officer on the cheap!’ So, worrying about others increased threefold. Not counting me; now when we got up to full strength, there would be thirty-three children and eleven Bren-Gun Carriers. The Company Commander, would be like a Boss plus a Union Rep, all wrapped up in one man, for me to answer to; similar to the ‘civvy street’ business world. When a supervisor is watched from above, and depended on from below.

So off we went again, nipping in and out, wherever we were needed. Often penetrating German defences, where American tanks could not. We in our low ‘Sardine Cans’, as the Yanks called them; could use the cover of folds in the ground, and Wadis. Backed up by the tanks of 17/21st Lancer and 16/5th, or Lothian and Border Horse in their Heavy Armoured Vehicles. We in our ‘wafer thin’ armour were more suitable for getting in and getting out, quickly. The Lancers came to our aid, when a small patrol of two carriers was testing the underbelly of the German defences near Medjes-el-bab.

It became very ‘hairy’, when Jerry brought up heavy weapons to assist his infantry; and tried to outflank us. We must have been under observation from way back, because a squadron of 17/21st tanks passed on either side of us. We had taken up a ‘hull down’ position on the crest of the hill, and were trying to hold off the advancing enemy. Thankfully we were ordered to withdraw. The infantry in our Motor Platoons, were also called upon to do all kinds of tasks. Like us, in our Scout Platoon ,’They never got bored!’ Opportunity would be a fine thing! They too lived from ‘hand to mouth’. Sleeping when they could, eating when they had the time, and keeping on, keeping on!

On the 7th of April 1943 the 1st Army, which we were part of, met up with the 8th Army, just below and South West of Sfax. Now the combined forces would push towards Tunis. Not easy, for Jerry fought tenaciously. Of course we were kept busy. It was reported that an Italian position still held out, having been bypassed. A Three-Carrier Patrol was sent to check them out. The ground was terrible, one minute sand the next rock and up and down Wadis. Below a slope and entering a cactus belt, a carrier shed a track. Corporal Sid Ferris and I went forward on foot. The remainder set up a defensive position and set to repairing the broken track. A fusillade of rifle fire pinned Sid and I down, followed by rough looking blokes in Burnooses, and firing from the hip. They pinched our boots and made us their prisoners.

At the top of the hill I heard a smart looking fellow in a natty uniform and medals, speak in French.

In my rough French I told him amid many swear words, that we were Anglais. The men on the hill were Goumiers, a formidable and vicious force of Arab soldiers under a French Officer. Our men had to withdraw; the firing missing us was making things difficult for them. Sid and I followed our carrier tracks for several miles in the dark, without weapons to defend us. They had mysteriously disappeared during capture.

I didn’t see the fall of Tunis. A German Mortar Bomb sent me, to the 95th Field Hospital in Algiers. It did me a favour really. Now I had crisp white sheets and pillow and a lady nurse, named Nurse Love. Not that there was much of that about. After about eight weeks, my wound through the biceps had recovered enough for me to rejoin my unit. I could still raise a pint, if one was offered.

The Company Commander sent a truck to pick me up and convey me to our mob, in the Vale Du Mort,

to be driven barmy by mosquito’s. Then we got an order to travel to Carthage, to Guard Winston Churchill and his wife. He was getting over a sickness.

Sad to say, on the way to Carthage on the Mediterranean coast. Corporal Sid Ferris, who was a temporary prisoner, along with me, had an accident. His carrier wandered too close to the edge of a crumbling dirt road in the dark, and turned over into a Wadi. The driver dug his way out with his bare hands. Sid lost his life. I will never forget him.

So after Africa, the next centre of operations was to be Italy. A different country, and a different kind of war. This time, amid foliage and trees where snipers hide and ambush is easier. I expect we’ll soon find out!