High Explosive Bomb at Morpeth Grove

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Morpeth Grove, Homerton, London Borough of Hackney, E9 7LH, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Sporadic air-raids went on all through 1943, but as Autumn came, bringing the dark evenings with it, the "Little Blitz" started, with plenty of bombs falling in our area and I got my first real experience of NFS work.

There were Air-Raids every night, though never on the scale of 1940/41.

By now, my own School, St. Olave's, had re-opened at Tower Bridge with a skeleton staff of Masters, as about a hundred boys had returned to London.

I was glad to go back to my own school, and I no longer had to cycle all the way to Lewisham every day.

Part of the School Buildings had been taken over by the NFS as a Sub-Station for 37 Fire Area, the one next to ours, so luckily none of the Firemen knew me, and I kept quiet about my evening activities in School. I didn't think the Head would be too pleased if he found out I was an NFS Messenger.

The Air-Raids usually started in the early evening, and were mostly over by midnight.

We had a few nasty incidents in the area, but most of them were just outside our patch. If we were around though, even off-duty. Sid and I would help the Rescue Men if we could, usually forming part of the chain passing baskets of rubble down from the highly skilled diggers doing the rescue, and sometimes helping to get the walking wounded out. They were always in a state of shock, and needed comforting until the Ambulances came.

One particular incident that I can never forget makes me smile to myself and then want to cry.

One night, Sid and I were riding home from the Station. It was quiet, but the Alert was still on, as the All-Clear hadn't sounded yet.

As we neared home, Searchlights criss-crossed in the sky, there was the sound of AA-Guns and Plane engines. Then came a flash and the sound of a large explosion ahead of us towards the river, followed by the sound of receding gunfire and airplane engines. It was probably a solitary plane jettisoning it's bombs and running for home.

We instinctively rode towards the cloud of smoke visible in the moonlight in front of us.

When we got to Jamaica Road, the main road running parallel with the river, we turned towards the part known as Dockhead, on a sharp bend of the main road, just off which Dockhead Fire-Station was located.

Arrived there, we must have been among the first on the scene. There was a big hole in the road cutting off the Tram-Lines, and a loud rushing noise like an Express-Train was coming from it. The Fire-Station a few hundred yards away looked deserted. All the Appliances must have been out on call.

As we approached the crater, I realised that the sound we heard was running water, and when we joined the couple of ARP Men looking down into it, I was amazed to see by the light from the Warden's Lantern, a huge broken water-main with water pouring from it and cascading down through shattered brickwork into a sewer below.

Then we heard a shout: "Help! over here!"

On the far side of the road, right on the bend away from the river, stood an RC Convent. It was a large solid building, with very small windows facing the road, and a statue of Our Lady in a niche on the wall. It didn't look as though it had suffered very much on the outside, but the other side of the road was a different story.

The blast had gone that way, and the buildings on the main road were badly damaged.

A little to the left of the crater as we faced it was Mill Street, lined with Warehouses and Spice Mills, it led down to the River. Facing us was a terrace of small cottages at a right angle to the main road, approached by a paved walk-way. These had taken the full force of the blast, and were almost demolished. This was where the call for help had come from.

We dashed over to find a Warden by the remains of the first cottage.

"Listen!" He said. After a short silence we heard a faint sob come from the debris. Luckily for the person underneath, the blast had pushed the bulk of the wreckage away from her, and she wasn't buried very deeply.

We got to work to free her, moving the debris by hand, piece by piece, as we'd learnt that was the best way. A ceiling joist and some broken floorboards lying across her upper parts had saved her life by getting wedged and supporting the debris above.

When we'd uncovered most of her, we used a large lump of timber as a lever and held the joist up while the Warden gently eased her out.

I looked down on a young woman around eighteen or so. She was wearing a check skirt that was up over her body, showing all her legs. She was covered in dust but definitely alive. Her eyes opened, and she sat up suddenly. A look of consternation crossed her face as she saw three grimy chaps in Tin-Hats looking down on her, and she hurriedly pulled her skirt down over her knees.

I was still holding the timber, and couldn't help smiling at the Girl's first instinct being modesty. I felt embarassed, but was pleased that she seemed alright, although she was obviously in shock.

At that moment we heard the noise of activity behind us as the Rescue Squad and Ambulances arrived.

A couple of Ambulance Girls came up with a Stretcher and Blankets.

They took charge of the Young Lady while we followed the Warden and Rescue Squad to the next Cottage.

The Warden seemed to know who lived in the house, and directed the Rescue Men, who quickly got to work. We mucked in and helped, but I must confess, I wish I hadn't, for there we saw our most sickening sight of the War.

I'd already seen many dead and injured people in the Blitz, and was to see more when the Doodle-Bugs and V2 Rockets started, but nothing like this.

The Rescue Men located someone buried in the wreckage of the House. We formed our chain of baskets, and the debris round them was soon cleared.

To my horror, we'd uncovered a Woman face down over a large bowl There was a tiny Baby in the muddy water, who she must have been bathing. Both of them were dead.

We all went silent. The Rescue Men were hardened to these sights, and carried on to the next job once the Ambulance Girls came, but Sid and I made our excuses and left, I felt sick at heart, and I think Sid felt the same. We hardly said a word to each other all the way home.

I suppose that the people in those houses had thought the raid was over and left their shelter, although by now many just ignored the sirens and got on with their business, fatalistically taking a chance.

The Grand Surrey Canal ran through our district to join the Thames at Surrey Docks Basin, and the NFS had commandeered the house behind a Shop on Canal Bridge, Old Kent Road, as a Sub-Station.

We had a Fire-Barge moored on the Canal outside with four Trailer-Pumps on board.

The Barge was the powered one of a pair of "Monkey Boats" that once used to ply the Canals, carrying Goods. It had a big Thornycroft Marine-Engine.

I used to do a duty there now and again, and got to know Bob, the Leading-Fireman who was in-charge, quite well. His other job was at Barclays Brewery in Southwark.

He allowed me to go there on Sunday mornings when the Crew exercised with the Barge on the Canal.

It was certainly something different from tearing along the road on a Fire-Engine.

One day, I reported there for duty, and found that the Navy had requisitioned the engine from the Barge. I thought they must have been getting desperate, but with hindsight, I expect it was needed in the preparations for D-Day.

Apparently, the orders were that the Crew would tow the Barge along the Tow-path by hand when called out, but Bob, who was ex-Navy, had an idea.

He mounted a Swivel Hose-Nozzle on the Stern of the Barge, and one on the Bow, connecting them to one of the Pumps in the Hold. When the water was turned on at either Nozzle, a powerful jet of water was directed behind the Barge, driving it forward or backward as necessary, and Bob could steer it by using the Swivel.

This worked very well, and the Crew never had to tow the Barge by hand. It must have been the first ever Jet-Propelled Fire-Boat

We had plenty to do for a time in the "Little Blitz". The Germans dropped lots of Containers loaded with Incediary Bombs. These were known as "Molotov Breadbaskets," don't ask me why!

Each one held hundreds of Incendiaries. They were supposed to open and scatter them while dropping, but they didn't always open properly, so the bombs came down in a small area, many still in the Container, and didn't go off.

A lot of them that hit the ground properly didn't go off either, as they were sabotaged by Hitler's Slave-Labourers in the Bomb Factories at risk of death or worse to themselves if caught. Some of the detonators were wedged in off-centre, or otherwise wrongly assembled.

The little white-metal bombs were filled with magnesium powder, they were cone-shaped at the top to take a push-on fin, and had a heavy steel screw-in cap at the bottom containing the detonator, These Magnesium Bombs were wicked little things and burned with a very hot flame. I often came across a circular hole in a Pavement-Stone where one had landed upright, burnt it's way right through the stone and fizzled out in the clay underneath.

To make life a bit more hazardous for the Civil Defence Workers, Jerry had started mixing explosive Anti-Personnel Incendiaries amonst the others. Designed to catch the unwary Fire-Fighter who got too close, they could kill or maim. But were easily recogniseable in their un-detonated state, as they were slightly longer and had an extra band painted yellow.

One of these "Molotov Breadbaskets" came down in the Playground of the Paragon School, off New Kent Road, one evening. It had failed to open properly and was half-full of unexploded Incendiaries.

This School was one of our Sub-Stations, so any small fires round about were quickly dealt with.

While we were up there, Sid and I were hoping to have a look inside the Container, and perhaps get a souvenir or two, but UXB's were the responsibility of the Police, and they wouldn't let us get too near for fear of explosion, so we didn't get much of a look before the Bomb-Disposal People came and took it away.

One other macabre, but slightly humorous incident is worthy of mention.

A large Bomb had fallen close by the Borough Tube Station Booking Hall when it was busy, and there were many casualties. The lifts had crashed to the bottom so the Rescue Men had a nasty job.

On the opposite corner, stood the premises of a large Engineering Company, famous for making screws, and next door, a large Warehouse.

The roof and upper floors of this building had collapsed, but the walls were still standing.

A WVS Mobile Canteen was parked nearby, and we were enjoying a cup of tea with the Rescue Men, who'd stopped for a break, when a Steel-Helmeted Special PC came hurrying up to the Squad-Leader.

"There's bodies under the rubble in there!"

He cried, his face aghast. as he pointed to the warehouse "Hasn't anyone checked it yet?"

The Rescue Man's face broke into a broad smile.

"Keep your hair on!" He said. "There's no people in there, they all went home long before the bombs dropped. There's plenty of dead meat though, what you saw in the rubble were sides of bacon, they were all hanging from hooks in the ceiling. It's a Bacon Warehouse."

The poor old Special didn't know where to put his face. Still, he may have been a stranger to the district, and it was dark and dusty in there.

The "Little Blitz petered out in the Spring of 1944, and Raids became sporadic again.

With rumours of Hitler's Secret-Weapons around, we all awaited the next and final phase of our War, which was to begin in June, a week after D-Day, with the first of them to reach London and fall on Bethnal Green. The germans called it the V1, it was a jet-propelled pilotless flying-Bomb armed with 850kg of high-explosive, nicknamed the "Doodle-Bug".

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by Researcher 249331 (BBC WW2 People's War)

In September 1940 the bombing raids really started. The warning would start wailing very loudly, the nearest siren being on top of Stoke Newington Police station, which was almost opposite where we lived. The bombers started coming over every night, the first few nights we sat on the stairs with blankets wrapped around us, shivering from cold - or was it fear? All of us were very quiet listening to the pulsating sound of the bombers overhead.

After a few nights of discomfort we started going into the basement of our next door neighbour. We couldn't use our cellar, as it was full of bundles of firewood that were in stock to be sold in the winter - they were sold for tuppence a bundle, in my father's greengrocery shop. The Vogue cinema was at the other end of of the block of buildings where our shop was situated. It was the sort of cinema that when the film was over you waded through monkey nut shells, on your way out to the exit.

The Blitz comes close to home

One night a bomb dropped onto a bus outside the Vogue. It made a large crater, and fractured a water main. After a while, water seeped into the cellar we were in. As we were hearing a lot of noise from the anti-aircraft guns, and from the dropping bombs, it was decided to go over the road to a proper shelter under the Coronation Buildings, where there was a very large air raid shelter.

We came out and saw the sky criss-crossed with searchlights. Whilst we were running across the road, a bomb landed with an enormous bang on the West Hackney Church. The blast blew out the windows of The Star Furnishing Company windows. The huge glass windows just disintegrated, and fell to the ground like a beautiful waterfall, with all the noise and dust. We rushed into the shelter, but amazingly we were all untouched.

During the day I used to watch the occasional dogfight overhead, and like most boys of my age (I was 11) at the time, my hobby was to go around looking for bits of shrapnel. One morning, coming home from the shelter over the road, I found an incendiary bomb on the pavement outside our shop. I stupidly picked it up, and was examining it when a policeman appeared and said 'I'll have that' - and ran across the road to the station with it.

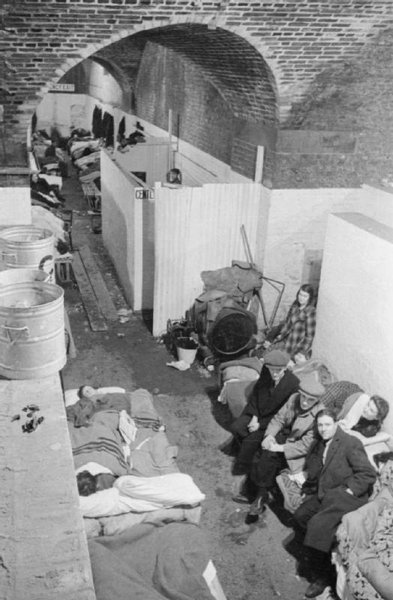

Shelter

Coronation Avenue buildings consists of a terrace of about 15 shops with five storeys of flats above. The shelter was beneath three of the shops.The back exit was in the yard between Coronation Avenue and another block of buildings, called Imperial Avenue. We went over the road to the shelter whenever there was a raid, and when the 'all clear' sounded in the morning, we would go back over the road, half asleep and very cold, and try to go back to sleep in a very cold bed.

The shelter consisted of three rooms. The front entrance was in the first room, the rear entrance was in the third room, which had bunk beds along one wall.The rooms were jam packed with people, sitting on narrow slatted benches. I would sit on a bench and fall asleep, and wake every now and then, and would find myself snuggled up to my mother and sister. My father had the use of one of the bunk beds, because the men were given priority, as they had to go to work.

Direct hit

On 13 October 1940, the shelter received a direct hit. We had settled down as usual, when there was a dull thud, a sound of falling masonry, and total darkness.

Somebody lit a torch - the entrance to the next room was completely full of rubble, as if it had been stacked by hand. Very little rubble had come into our room. Suddenly i felt my feet getting very cold, and I realised that water was covering my shoes. We were at the end of the room farthest from the exit. I noticed my father trying to wake the man in the bunk above him, but without success - a reinforcing steel beam in the ceiling had fallen down and was lying on him.

The water was rising, and I started to make my way to the far end, where the emergency exit was situated. Everybody seemed very calm - with no shouting or screaming. By the time I got to the far end, the water was almost up to my waist, and there was a small crowd clamberinig up a steel ladder in a very orderly manner. Being a little more athletic than some of them, and very scared, I clambered up the back of the ladder to the top, swung over, and came out into the open.

It was very cold and dark, and I was shivering. The air was thick with brick dust, which got into my mouth, the water was quelching in my shoes. I still dream of, and recall, the smell of that night, and the water creeping up my body. My parents and my sister came out, and we couldn't believe the sight of the collapsed building. My brother had been out with a friend - so was not hurt, and we were all OK.

My mother, sister and I went over to number 6, and my father and brother stayed to see if they could help in any way. Some bricks had smashed the shutters in front of the shop, and had to be replaced with panel shutters, which had to be removed morning and evening. The windows were blown out, and were replaced temporarily with a type of plastic coated gauze.

Afterwards

The next morning, we were told that only one person had survived in the other two rooms, and about 170 people had been killed. (In recent years I have been to Abney Park cemetery, where there is a memorial stone, with names of a lot of the victims who must have died in our shelter.)

There was a huge gap in our building, on about the third floor. There was part of a floor sticking out, with a bed on it. Someone said the person in it was OK, but this story might just have been hearsay.

A lot of the women used to bring photographs of their families to show each other during the long periods of waiting in the shelter. That evening my mother had brought a handbag full of photos to show some women, and fortunately she had not gone into the other room to show them. The photos were never recovered. My sister said she was alright, until she went up into our parents room the next morning, and saw soldiers arriving outside, with shovels - then she started crying (she was 15 years old).

A few days later, I saw men wearing gauze masks bringing out bodies, and placing them in furniture vans. Having seen bodies since, this is the only thing that comes back in my dreams - the furniture vans and the water.

Where next?

Having nowhere to go for shelter, my parents decided that we would go to the Tube station to sleep. We would close the shop early, and with bundles of blankets go to Oxford Circus station, via Liverpool Street, and sleep for the night on the platform. When the trains started to run the next morning, we would get up feeling very dry and grubby having slept fully clothed all night. We had to wait patiently until the platform cleared, and then back we went to Liverpool Street, and the 649 trolley bus home.

One night we heard a lot of noise above, and the next morning I went up to have a look, and saw a lot of Oxford Street burning. On the way home by trolley bus - amazingly they were still running - we went through Shoreditch, and saw fires still burning. But the motto everwhere was business as usual.

Looking for shrapnel when I got home, I saw an Anderson shelter in Glading Terrace that had received a direct hit - it was just a twisted lump of metal. The bombing was very heavy and some areas were roped off because of unexploded bombs. But it was a pleasant surprise when the King and Queen visited Stoke Newington - that was when I first had my photo taken with the Queen.

Photo with Queen Elizabeth

A water main near us had been had been hit, and my sister and I were trying to find a bowser lorry to get some water, when somebody told me that the King and Queen were in Dynevor Road, nearby. So I ran there, and managed to sqeeze through to the front of the crowd. The Queen made some comment about me to the woman behind me. Some time later my sister saw the photograph taken at the time, and contacted the newspaper and got some copies.

Eventually my parents arranged for my sister and me to be evacuated, and my brother (who was 19 years old) was posted to North Africa. He went from Alemein right through to Italy, and came home and went to the continent - finishing his war in Germany.

Contributed originally by peter (BBC WW2 People's War)

Setting the scene:

My Dad was the headmaster of a Junior Boys School, Attley Road, in East London, just round the corner from Bryant and Mays Match Factory.

I went to the local Infants and Junior School, "Redbridge" in Ilford, Essex

The transmission of news and public information was by the BBC Wireless, the Cinema News Reels and the National Newspapers. The whole impression, looking back, was of an extremely formal (and, as it later turned out, easily manipulated) information system.

Evacuation

The news had swung from the optimism of Munich to an increasingly pessimistic view. I sensed, even at my age of nine, that most people thought that the war with Germany would come and come soon. My reaction to all this and that of most of my compatriots was one of excitement tinged with some trepidation.

Every school in the area of greater London (and Manchester, Liverpool etc. I now know) had made plans to evacuate all children whose parents had agreed for them to so go. As my father was an Head Teacher it was decided that I with my mother as a helper would go with his school if and when the call came.

We started to prepare ourselves for what to me and thousands more children was to be the start of a great adventure. We had been issued with rectangular cardboard boxes containing our gas masks and these were mostly put into leatherette cases with a shoulder strap. We also each were to have an Haversack to hold a basic change of clothes, pyjamas, wash bag and so on.

During that late August 1939 we had a rehearsal for evacuation and every school met up in the playgrounds and were marched off to the nearest Underground Station. The next stage to one of the Main Line Stations was for the real thing only.

We each had a label firmly attached to a button-hole with our name, address and school written on. Each child had to know its group and the responsible teacher. This tryout was to prove its worth very soon.

The news was getting worse by the day. Germany then invaded Poland and it was obvious that the declaration of war was imminent.

At 11 am on Sunday the 3rd of September the Wireless announced that despite all efforts we were at war with Germany. It was, in a funny kind of way, an anticlimax.

My memory fails me as to the precise date of our evacuation. It was, I believe, a day or so before the war started, probably the 1st of September, no matter, the excitements, traumas and all those myriad experiences affecting literally millions of children and adults were about to start.

The call came. We repeated our rehearsal drill, arriving, in our case, by bus and train to Bow Road station and walking down Old Ford road to Attley Road Junior School. All the children that were coming, the teachers and helpers assembled in the play ground. Rolls were called, labels checked, haversacks and gas masks shouldered. We were off on the great adventure!

We "marched" off with great aplomb to waves and tears from fond parents who did not know when they would see their kids again, if ever.

The long snake of children and teachers arrived at Bow Road Underground Station and were shepherded down onto the platform where trains were ready and waiting.

Looking back, the organisation was fantastic. Remember, this was in the days before computers and automation! It was made possible by shear hard work and attention to detail. Tens of thousands of children were moved through the Capital transport system to the Main Line Stations in a matter of a few hours.

Our train arrived at Paddington by a somewhat roundabout route and we all disembarked making sure to stick together. We walked up to the platforms where again the groups of children were counted by their teachers. Inspectors were busily marshalling the various school groups onto awaiting trains.

We boarded our train together with several other schools. It was a dark red carriage, not, as I remember, the GWR colours, and settled ourselves down. The teachers were busy checking that nobody was missing and we then got down to eating whatever packed food we had brought with us. Many of the smaller children were beginning to miss their Mum's and the teachers and helpers had their work cut out to calm them down. Remember that most of these children had never been far from the street where they lived.

Eventually, the train got steam up and slowly moved out of the station. This would be the last time some of us would see home and London for a long time but, we were only kids and had no idea of what the future would hold. To us it was the great adventure.

The train ride seemed to go for ever! In fact we did not go that far, by mid-afternoon we arrived at Didcot.We disembarked and assembled in our groups in a wide open space at the side of the station where literally dozens of dark red Oxford buses were waiting, presumably for us.

It was at this point, according to my father, that the hitherto brilliant organisation broke down. A gaggle of Oxford Corporation Bus Inspectors descended on the assembled masses of adults and children and proceeded to embus everyone with complete disregard to School Groupings.

The buses went off in various directions ending up at village halls and the like around Oxford and what was then North Berkshire.

My father was by this time frantic that he had lost most of the children in his care (and some of the staff) and no-one seemed at all worried!

The story gets somewhat disjointed now as a combination of excitement and tiredness was rapidly replacing the adrenaline hitherto keeping this nine year old going.

Anyway, what can't be precisely remembered can be imagined! We, as mentioned, went off in this red bus to a destination unknown to all but the driver (and the inspector who wouldn't tell my Dad out of principle) - I'm sure, in retrospect, that this is when the expression "Little Hitler" was coined!!

On our bus were about fifty odd children and six or seven teachers and helpers. Most, but not all, were my dad's, but where were the rest of the two hundred or so kids he'd started out with? It was to take several days before that question was to be answered.

After some hour or, so two buses drew up together in a village and parked by a triangular green. There was a large Chestnut tree at one corner and a wooden building to one side. There was also a large crowd of people looking somewhat apprehensive.

We all picked up our haversacks and gas masks and got off the buses, marshalled by the teachers into groups and waited.

Ages of the children varied between seven and fourteen and naturally enough there were signs of incipient tears as we all wondered where we were going to end up. For me it wasn't so bad because I had Mum and Dad with me - most of them had never been separated from their families before.

A large man in a tweed suit, he turned out to be the Billeting Officer, seemed to be organising things and he kept calling out names and people stepped out from the crowd and picked a child out from our bunch. It closely resembled a cattle market!

My Father, naturally, was closely involved, monitoring the situation and trying to keep track of his charges while all this was going on.

Eventually, when it was virtually dark, everyone had been found homes in and around the village. Some brothers had been split up but, most of the kids were just glad to have somewhere to lay their heads.

While all this was happening we found out where we were; not that it meant much to me then. We were in a village called Cumnor situated in what was then North Berkshire and about four miles from Oxford.

At long last, after what seemed to me to be for ever, I was introduced to our benefactors who we were to be billeted with.They were a pleasant seeming couple of about middle age & we stayed with them for about 6 months before finding a cottage to rent.

The Village at war

It is difficult to include everything that happened during that period of my life in any precise order. Therefore, I have included the remembered instances and effects relating to the war.

The first effect was, undoubtedly, the upheaval in agriculture. Suddenly fields that had lain fallow ever since the last war were being ploughed up to grow crops. Farmers who had been struggling to make ends meet for years were actually encouraged and helped to buy new equipment to improve efficiency.

The war didn't really touch the village until the invasion of France and Dunkirk. That is, of course, not to say that wives and girl-friends weren't worried about their men folk serving in the forces.

Then, all of a sudden, you heard that someone was missing or, a POW. The war was suddenly brought home with a vengeance to everyone. Also, the news on the wireless and in the newspapers was very bad, although usually less so than the reality.

One of the village girls had a boy-friend who was Canadian. He had come over to Britain to volunteer and was in the RAF. He was a rear gunner in a Wellington bomber and was shot down over Germany during 1942.

For a long time there was no news of him and then Zena, her name was, heard that he was a POW. At the end of the war he returned looking under-weight but, happy and there was a big party to celebrate his return and where they got engaged! a truly happy ending.

Another memory, this time not a happy one, was the son of some friends, who was a Pilot in the Fleet Air Arm was shot down during the early part of the war and killed in action.

There was a Polish Bomber Squadron based at Abingdon and they were a mad lot and frequented a pub near to Frilford golf club called "The Dog House".

As the war wore on so the aircraft changed. Whitley and Wellingtons were replaced by Stirling's and Halifax's. finally, the main heavy bomber was the Lancaster. These used to drone over us from Abingdon and other local airfields night after night.

We also started to see a lot of Dakota's often towing Horsa gliders. In fact, several gliders came down nearby during one training exercise and one hit some power cables, luckily without major injuries to the crew.

More and more of the adult male and female villagers had disappeared into the forces and more and more replacements were needed to work the farms.

The result of all this was to put at a premium such labour as was available. This meant Land Army girls, POW's and me and my friends!

Various Army units appeared from time to time on exercises and the like.

It sounds strange now but, remember that everyone was travelling around at night with the merest glimmer of a light. Army lorries just had a small light shining on the white painted differential casing as a guide to the one behind. Cars had covers over their head-lights with two or, three small slits to let out some light.

Then there was the arrival of the Americans - I believe it would have been during 1942 that they were first sighted. They were so different to our troops - their uniforms were so much smarter and their accents were very strange to us then.

They established a tented camp just up the road from the Greyhound at Besselsleigh and naturally it became their local. This was viewed with mixed feelings by the locals as beer was in short supply and the Yanks were drinking most of it!

Their tents were like nothing we had ever seen then - They were square and big enough to stand up in without hitting the roof. They were each fitted up with a stove. Nothing at all like the British Army "Bell tents".

We all got used to seeing Jeeps and other strange vehicles on our roads, they in turn, got used to our little winding lanes and driving on the wrong side.

The Americans were very keen to get on with the locals and when invited to someone's home would usually bring all sorts of goodies such as tinned food, Nylon's for the girls and sweets for the kids. They knew that the villagers didn't have much of anything to spare at that time.

A British Tank Squadron came into the village at one time. They were on the inevitable exercise and were parked down near Bablockhythe, in the fields. We boys went down to see them and found about four or, five Cromwell (I think that was their name) Tanks parked with their crews brewing up. Naturally, the sight of all that hardware was exciting to us and we were allowed up and into the cockpit of one.

During the build up for the D day landings there were convoys going through the village day and night. There was every sort of vehicle you could possibly think of - Lorries, Troop Carriers, Bren Gun Carriers, Tanks of all shapes and sizes, Self-propelled Guns, Despatch riders and MP's to control and direct the traffic.

This almost continuous stream continued for what must have been a fortnight before it gradually quietened down to something approaching normality.

Naturally, during this time and whenever I was home from school I would walk up to the corner just below the War Memorial and watch these convoys with great interest and excitement.

There were troops of every nationality including French, Polish, Czech, Dutch, Canadians, Anzacs, Americans and so on. Obviously, the build up for the second front was beginning and something big would happen before too long!

Just before all this activity we had seen dumps of what seemed to be ammunition along local country roads and this was further evidence that the big day was getting close.

People's morale was starting to improve by this time. It had never been broken but, for three years the news had been mostly bad or, at the very least, not good and people's resistance had begun to wane a little.

North Africa had been a great victory and this coupled with the nightly bombing raids over Germany and the day raids by the Americans as well, really cheered people up and convinced them that we had turned the corner.

Everyone, including us teenager's used to sit with our ears glued to the wireless when there was a news bulletin.

People, during that wartime period in their lives, were much closer to each other than they had ever been.

Back to 1944 - The build up of men and materials continued and there was a constant stream through the village. Then a period of calm followed for a week or, so. And then came the news of the D Day landings - we all sat with our ears glued to the wireless whenever we could. For the first few days the news was fairly sparse and we didn't really know if the invasion was going to work.

After a week or, so the news began to be more positive and our hopes were raised. There were set backs and of course, there were casualties but, we were getting closer to the end of the war.

Then one Autumn morning in very misty conditions we heard lots of aircraft overhead. Through the patches of hazy sky we could discern dozens of Dakota's and the like with Gliders in tow. A few hours later they were to return with their gliders still hooked on.

Wherever they had been going to drop their tows must have been covered in the fog that had persisted most of that day over us. The result of this was gliders being released all over the place as the Dakotas prepared for landing.

A day or, so later the same "exercise" was repeated and this time the planes returned without their gliders. The battle of Arnhem had begun.

So the war continued for several months but, one could sense that the end was drawing ever closer.

The war in the Far East was to continue for several more months but, at last, the main enemy had been defeated.

How did all this affect us? In all sorts of ways - there were preparations for a General Election. The soldiers began to come home and there were frequent welcome home parties.

Food was still on ration as was petrol and clothes. So, there wasn't any sudden improvement to the rather dreary existence we had all got used to. In fact, it was a bit of an anticlimax. One of the few nice things to happen in that immediate post-war time was the return of Oranges and Bananas to the shops. We hadn't seen these for six whole years!

Basically, The United Kingdom was worn-out and broke by the war's end and to a great extent so were it's people. Our former enemies were helped by the USA to rebuild their countries and industries as also were France and the Lowlands countries but, we had to try to help ourselves for no-one else was going to.

Peter Nurse 1994

Biddulph

Contributed originally by lilianhenbrooks (BBC WW2 People's War)

In August 1935 my mother died of breast cancer. We lived in Dagenham at the time. She left my father, Frederick, my sister, Rose and me, Lilian. After she died we moved to Bethnal Green to be nearer family. My father was working and had found it difficult bringing us girls up by himself.

I was partially blind and went to the Daniel Street blind school but had always wanted to go to the school round the corner in Wilmot Street. My father was friendly with a lady called Ann and I knew her as Aunt Ann. She would make me tea after school. My father used to take her out a couple of times a week.

In 1939 my father and my friend, Beatty's parents, discussed sending Beatty and me to stay with Beatty's Aunty in Southport. Her surname was Chick. It was just before the start of the war and they thought it would be best for us. We packed up our things and were put on a train to Southport and told to look for the clock when we got to our destination and wait under it, where we would be picked up by Aunty, and we would recognise her because she would be wearing a brooch.

Well we got off the train and waited under the clock, as directed, which seemed to be along time, but we were determined not to move. The porter asked us in a broad Lancashire accent what we were doing. I replied, in my cockney accent, that we had been told to wait under the clock. He seemed satisfied with this and walked off. Eventually Aunty came and colected us and took us home. I went to an ordinary school in Southport then. After 7 months we returned to Bethnal Green.

We were back in London by 1940. I spent the next 2 months going to the school in Wilmot Street because troops were billeted at the blind school as the war had started by this time. This made me feel that I was the same as the other girls and I liked it there.

I was 12 years old and was about to be evacuated for the second time in June 1940. With father being at work all day it was thought best that I should go. Rose was older than me and working up town. Beatty was also older than me and had turned 14 years. She wanted to start work and wouldn't be coming along this time. A programme of evacuation had already started from London schools even though the Blitz had not begun at this time. Eventually though, many people started to return to London prematurely, thinking it was safe, only to be killed when the bombing started.

We all assembled in the school yard for 9.00 a.m. equipped with suitcase, gasmask and a numbered label on the lapel of our coats. Buses took us to King's Cross to await the trains. A few paretns did come to say goodbye and there was plenty of hugs and sobs. It was chaos at King's Cross with children and babies everywhere. Older ones in groups, babies in long prams. Officials everywhere checking numbers etc., but no one would say where we were going. It was rumourned Cornwall but no one was sure.

It was not until we reached Cardiff that we finally, after many questions, were told we were heading for Rhymney, Monmouthshire, S Wales. People didn't travel very much in those days, especially us East Enders, we thought of Wales as being another country. The thought of being so far away from home made even those that had not yet had a weep, cry. A friend of mine who was on the train, Susan Braithwaite. She had seven sisters and when she later got married in Bethnal Green all her sisters were bridesmaids. We kept in contact for a while when I moved to Leeds and then we stopped writing.

On the train also was another girl, called Phyllis, she was Jewish, she was crying and we got together for some comfort. Some of the other children were part of one family. They were saying that they were not going to be split up. Phyllis and I said that we would stick together and try to stay in the same house.

When we arrived at the station of Rhymney we were given hot cocoa drinks and biscuits by the ladies serving from trolleys on the platform and then off we set again. Two buses met us at the station to take us to a school. There we filed through a room where we were weighed, measured, examined for head lice and a spatula put over our tongues with mouths wide open and having to say "Ah"! Then into another classroom to be sorted out for accommodation. It wasn't possible for my new found friend and I to stay in the same house together, there just wasn't room but in the end we did get next door to each other.

At first I stayed with a couple called, Isaac Price and his wife and they lived in a one up one down miners cottage. They had a 16 year old daughter, called Alice. Isaac was on a regular night shift. I slept with Alice and Mrs Price slept in a single bed in an alcove of the bedroom. Before we went to bed for that first day we just had time for a snack. That first day had been a very long day. I laid in bed planning in my head, how I was going to get back to London even if I had to walk as I didn't want to stay in this strange place. People in the village were very kind and helpful and it all got better as the days went on.

The people I was staying with had another daughter who was returning home from service somewhere down South. There would be no room for me in the small house. Mrs Price's brother, Will, who was a widower, was getting married again very soon. It was arranged that I would move in with them straight after the wedding.

I moved in with them and they lived in a two bedroomed end terrace house with a back garden. I had a bedroom to myself and was so well looked after as if I was their own daughter. They had no family and I called them Uncle Will and Aunt Sally. He was a Baptist and she was a Congregationalist. They both carried on going to their respective churches. They went to church 3 times a day on a Sunday.

I used to go to Sunday school in the morning and then again with Aunt Sally and found myself singing in the choir with Aunt Sally. They had such lovely voices. There was also other things that I did at the Chapel during the week so my time was kep occupied.

One memorable Sunday there wasa terrific thunderstorm and we just couldn't leave the house for evening chapel. Hailstones thundered down like mothballs and lightening struck chimneys and roofs. We being the top house of the sloping street just had a couple of inches inside the house but below in the village centre hailstones were up to your waise and the mud washed down from the mountains ruined lots of homes. It was as bas as being bombed.

Saturday was the time to help out with the housework and I got 9d. and taken to the local cinema for the first house performance.

We went to school in a disused chapel and had equipment sent from London. We were separated from the Welsh children because of this and only came in contact with them after school when we met them in the street and played with them. We had been accompanied down to Wales by our own teachers, Mrs Meals and Miss Long. All ages joined in with all the lessons and we had good PE and both sexes played cricket and rounders etc., in the local park. Later our teachers had to go back to London and a Welshman took over. He went into the RAF later on.

When we were first evacuated some women and mothers came with us to Wales but later returned to London with their youngest children leaving the oldest in Wales.It was heard later that some of the families had been killed in the Blitz.

In December, 1940, my father died of pneumonia. A letter arrived for Mr & Mrs Price and my Uncle Will had to tell me

the bad news. He told me my father had gone to Jesus. I was in shock and couldn't believe it as I was very upset. I hadn't seen my father all the time I was in Wales, I loved my father. I yelled at him 'there is no Jesus'. I was bit hysterical and he slapped my face to calm me down.

I stayed for a further 6 months in Wales. I was in Rhymney about 18 months in all. My stay in Rhymney on the whole was a happy one and I was very fortunate to have such lovely people looking after me.

During the time I was in Wales my sister, Roase, had met her fiancee. He went through the awful experience of being at Dunkirk. He came from Leeds, West Yorkshire. Rose had met his family and had written to me to tell me about them and how they were willing to take me so that we could be together. They were also willing to look after Queenie, our Yorkshire Terrier. So later on in 1941 Rose took charge of me and came to collect me to take me to Leeds and I had to say farewell to my new found family in Rhymney. I eventually

settled down in Leeds where I made my home and had my own family, this being another story.

Contributed originally by Angela & Dianna (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was written by Angela's mother, Dobbie Dobinson:

It was 1936. I was just 16 and looking for a bit of excitement, so I was quite interested when I was invited to a Blackshirt meeting. I was told it could get a bit unruly, but the boys were really dishy.

The meeting was in south east London and was bursting at the seams with young people, male, female, black, white - they were all there. I couldn't believe that politics were uppermost in their minds, and I'm sure it wasn't in mine.

I was completely bowled over by the appearance of the members - girls and boys alike. The immaculate black silk shirt and tie. The slim trousers tucked into long black shiny boots. Topping it all was the wide leather belt with the large shiny buckle with the Blackshirt emblem. I learned later that it wasn't just decorative, but had a slightly more sinister use. Under the buckle were several sharp spikes, which could be released when the belt was removed and became rigidly upright. It formed an extremely effective weapon when whirled around among would-be attackers.

I decided to become a member, with all arrangements for my uniform to be delivered ASAP. My parents, needless to say, were very disapproving, and that's putting it mildly, but they had always encouraged us to learn by our own mistakes - and they both reckoned this was a big one!

So far, I had only attended local meetings, but once I had my uniform I was keen to go further afield and hear the better speakers. Sir Oswald Mosley, our leader, was due to speak in the East End of London, always reckoned to be a very lively venue. The great man arrived to address what was a really huge audience. There were Brownshirts, Greenshirts, Communists and a very high proportion of the Jewish community.

To me he looked rather like a doll that had been very carefully dressed. Nothing was out of place. His hair was perfect for the then popular Brylcreem and his little moustache looked as though it had been crayoned on his upper lip. His boots shone like glass and when he gave the salute and clicked his heels I expected them to crack!

He began his speech, but it didn't last long. There was a lot of catcalling and he seemed to have difficulty in holding the interest of the crowd or controlling it. But his deputy arrived to save the day, introduced as William Joyce.

I recognised him at once, although it was quite some time since I'd seen him. His sister Joan had been in my class at Dulwich Hamlet School and I eventually met all his family and it was a very lovely one. Joan had a twin called James, then came Quentin, then Frank and last came William. They were all very happy and confident people and I much enjoyed their company.

As soon as William started speaking the atmosphere changed completely, and I was to learn from future meetings that he had the ability to manipulate a crowd like no-one I had ever heard before.

From then on I never missed one of his meetings, but of course they could be pretty rowdy and this was when I saw the belts put to good use. The opposition was not to be outdone, however, and whirled long pieces of thick string with a raw potato attached to the end with several razor blades stuck in at different angles. Both weapons were not to be argued with for long, but if you were unwise enough to stand your ground an ambulance was quickly required.

It was at one such meeting when things became really out of hand and the police, who always attended our meetings, moved in in force. They had evidently decided that enough was enough and rounded up a number of youngsters, including me. We were bundled into a large police van, the door of which was covered with a metal frame. It felt like being in a cage and the atmosphere became very subdued.

The younger ones, including me, were made to give the usual details and were asked where our parents could be contacted. They were told to come and pick us up. Most parents arrived in a very short time and it was made clear there would be a whole lot of trouble when they reached home. My father decided otherwise - he obviously felt it might give me food for thought if he left me until the next morning.

Actually, although I didn't get any sleep, I learned a great deal about a policeman's lot during the small hours and it was not a happy one. They dealt with drunks, street people and some very abusive people, and my vocabulary increased considerably! A very nice sergeant gave me cups of strong tea with lots of sugar and two arrowroot biscuits. I think he knew I wasn't a real criminal, just a rather stupid brainwashed youngster, and with hindsight I have to agree with him.

I left the Blackshirts when I met the boy who was eventually to become my husband. By then it was 1938 and preparations were going on for war, like sandbags, shelters and gas masks. My boyfriend, who had joined the Territorials, was called up and was whisked off to the Cornwall coast on a London bus, and there given a rifle but no ammunition!

War finally came and sitting alone one evening I turned on my little battery radio and was astounded to hear a voice I knew only too well saying 'Germany calling! Germany calling!' The voice still held an audience even though the messages raised the blood pressure of any red-blooded Englishman. These messages continued every evening and eventually William Joyce came to be known as Lord Haw Haw. He had left this country and joined forces in Germany with our enemies and therefore became a traitor. The war ended and William was brought home, to be tried and sentenced to death by hanging.

I clearly remember the morning the sentence was carried out. I got up early and left the family sleeping; I sat quietly by the window until the clock struck the hour and I knew it was all over and William was no more. But he had stuck to his beliefs till the end and I think, in his case at least, he really believed in the Blackshirt cause, misguided as it was. But as he was often heard to say: 'You can't win 'em all.'