High Explosive Bomb at St Andrews Way

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

St Andrews Way, Bromley-by-Bow, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, E3 3PJ, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by angaval (BBC WW2 People's War)

It is September 1940 and I am returning from Chrisp Street Market with my mother. I'm nearly seven and I've come back to London after being evacuated to Glastonbury during the 'phoney war'. It's a lovely warm evening and my mum is anxious to get back home with her shopping.

As we begin to turn into Brunswick Road, we hear the sound of gunfire - not unusual, as we live near the East India Docks and there is frequent gunnery practice. But then we hear the planes and the air raid sirens. ARP wardens are running about blowing whistles, shouting, 'Take cover, take cover!' We start running the last few yards home.

My dad is panicking and my nana (who speaks little English) is hysterical. We then all bolt into the Anderson shelter in the back yard, just as the first bombs start exploding. My Dad hates the Anderson as it's always full of spiders and he's scared of them. The noise is horrendous. Every time a bomb falls near, everything shakes. Above us there is the 'voom, voom, voom' sound of the planes. The ack-ack guns make a hollow booming noise and the Bofors make a rapid staccato rattle. It seems to go on for hours and then, suddenly, there is a pause, then the 'all clear'.

Stunned by the noise, we emerge. The house is still standing and doesn't seem damaged. We go out through the front door to see a scene which even now I recall as vividly as when it happened. The entire street is choked with emergency vehicles - ambulances, fire engines - all clanging their bells. The gutters and pavements are full of writhing hoses like giant snakes, and above... the sky. The sky - to the south, still a deep, beautiful blue, but to the north a vision of hell. It is red, it is orange, it is luminous yellow. It writhes in billows, it is threaded through with wisps and clouds of grey smoke and white steam. All around there are shouts and occasional screams, whistles blow and bells clang.

The neighbours stand around in small groups. They talk quietly and seem as dazed as us. Apparently most of the flames are from the Lloyd Loom factory down the road, which has taken a direct hit. The gutters run with water, soot and oily rainbows and the reflections of the fiery sky. Our respite does not last long. About 20 minutes later, another alert, we are back in the Anderson, and it all begins again.

The noise makes my knees hurt. When I tell my mother, she laughs and says it's growing pains. Maybe, maybe, but for the rest of the war; whenever there was a raid my knees always ached!

Contributed originally by peter (BBC WW2 People's War)

Setting the scene:

My Dad was the headmaster of a Junior Boys School, Attley Road, in East London, just round the corner from Bryant and Mays Match Factory.

I went to the local Infants and Junior School, "Redbridge" in Ilford, Essex

The transmission of news and public information was by the BBC Wireless, the Cinema News Reels and the National Newspapers. The whole impression, looking back, was of an extremely formal (and, as it later turned out, easily manipulated) information system.

Evacuation

The news had swung from the optimism of Munich to an increasingly pessimistic view. I sensed, even at my age of nine, that most people thought that the war with Germany would come and come soon. My reaction to all this and that of most of my compatriots was one of excitement tinged with some trepidation.

Every school in the area of greater London (and Manchester, Liverpool etc. I now know) had made plans to evacuate all children whose parents had agreed for them to so go. As my father was an Head Teacher it was decided that I with my mother as a helper would go with his school if and when the call came.

We started to prepare ourselves for what to me and thousands more children was to be the start of a great adventure. We had been issued with rectangular cardboard boxes containing our gas masks and these were mostly put into leatherette cases with a shoulder strap. We also each were to have an Haversack to hold a basic change of clothes, pyjamas, wash bag and so on.

During that late August 1939 we had a rehearsal for evacuation and every school met up in the playgrounds and were marched off to the nearest Underground Station. The next stage to one of the Main Line Stations was for the real thing only.

We each had a label firmly attached to a button-hole with our name, address and school written on. Each child had to know its group and the responsible teacher. This tryout was to prove its worth very soon.

The news was getting worse by the day. Germany then invaded Poland and it was obvious that the declaration of war was imminent.

At 11 am on Sunday the 3rd of September the Wireless announced that despite all efforts we were at war with Germany. It was, in a funny kind of way, an anticlimax.

My memory fails me as to the precise date of our evacuation. It was, I believe, a day or so before the war started, probably the 1st of September, no matter, the excitements, traumas and all those myriad experiences affecting literally millions of children and adults were about to start.

The call came. We repeated our rehearsal drill, arriving, in our case, by bus and train to Bow Road station and walking down Old Ford road to Attley Road Junior School. All the children that were coming, the teachers and helpers assembled in the play ground. Rolls were called, labels checked, haversacks and gas masks shouldered. We were off on the great adventure!

We "marched" off with great aplomb to waves and tears from fond parents who did not know when they would see their kids again, if ever.

The long snake of children and teachers arrived at Bow Road Underground Station and were shepherded down onto the platform where trains were ready and waiting.

Looking back, the organisation was fantastic. Remember, this was in the days before computers and automation! It was made possible by shear hard work and attention to detail. Tens of thousands of children were moved through the Capital transport system to the Main Line Stations in a matter of a few hours.

Our train arrived at Paddington by a somewhat roundabout route and we all disembarked making sure to stick together. We walked up to the platforms where again the groups of children were counted by their teachers. Inspectors were busily marshalling the various school groups onto awaiting trains.

We boarded our train together with several other schools. It was a dark red carriage, not, as I remember, the GWR colours, and settled ourselves down. The teachers were busy checking that nobody was missing and we then got down to eating whatever packed food we had brought with us. Many of the smaller children were beginning to miss their Mum's and the teachers and helpers had their work cut out to calm them down. Remember that most of these children had never been far from the street where they lived.

Eventually, the train got steam up and slowly moved out of the station. This would be the last time some of us would see home and London for a long time but, we were only kids and had no idea of what the future would hold. To us it was the great adventure.

The train ride seemed to go for ever! In fact we did not go that far, by mid-afternoon we arrived at Didcot.We disembarked and assembled in our groups in a wide open space at the side of the station where literally dozens of dark red Oxford buses were waiting, presumably for us.

It was at this point, according to my father, that the hitherto brilliant organisation broke down. A gaggle of Oxford Corporation Bus Inspectors descended on the assembled masses of adults and children and proceeded to embus everyone with complete disregard to School Groupings.

The buses went off in various directions ending up at village halls and the like around Oxford and what was then North Berkshire.

My father was by this time frantic that he had lost most of the children in his care (and some of the staff) and no-one seemed at all worried!

The story gets somewhat disjointed now as a combination of excitement and tiredness was rapidly replacing the adrenaline hitherto keeping this nine year old going.

Anyway, what can't be precisely remembered can be imagined! We, as mentioned, went off in this red bus to a destination unknown to all but the driver (and the inspector who wouldn't tell my Dad out of principle) - I'm sure, in retrospect, that this is when the expression "Little Hitler" was coined!!

On our bus were about fifty odd children and six or seven teachers and helpers. Most, but not all, were my dad's, but where were the rest of the two hundred or so kids he'd started out with? It was to take several days before that question was to be answered.

After some hour or, so two buses drew up together in a village and parked by a triangular green. There was a large Chestnut tree at one corner and a wooden building to one side. There was also a large crowd of people looking somewhat apprehensive.

We all picked up our haversacks and gas masks and got off the buses, marshalled by the teachers into groups and waited.

Ages of the children varied between seven and fourteen and naturally enough there were signs of incipient tears as we all wondered where we were going to end up. For me it wasn't so bad because I had Mum and Dad with me - most of them had never been separated from their families before.

A large man in a tweed suit, he turned out to be the Billeting Officer, seemed to be organising things and he kept calling out names and people stepped out from the crowd and picked a child out from our bunch. It closely resembled a cattle market!

My Father, naturally, was closely involved, monitoring the situation and trying to keep track of his charges while all this was going on.

Eventually, when it was virtually dark, everyone had been found homes in and around the village. Some brothers had been split up but, most of the kids were just glad to have somewhere to lay their heads.

While all this was happening we found out where we were; not that it meant much to me then. We were in a village called Cumnor situated in what was then North Berkshire and about four miles from Oxford.

At long last, after what seemed to me to be for ever, I was introduced to our benefactors who we were to be billeted with.They were a pleasant seeming couple of about middle age & we stayed with them for about 6 months before finding a cottage to rent.

The Village at war

It is difficult to include everything that happened during that period of my life in any precise order. Therefore, I have included the remembered instances and effects relating to the war.

The first effect was, undoubtedly, the upheaval in agriculture. Suddenly fields that had lain fallow ever since the last war were being ploughed up to grow crops. Farmers who had been struggling to make ends meet for years were actually encouraged and helped to buy new equipment to improve efficiency.

The war didn't really touch the village until the invasion of France and Dunkirk. That is, of course, not to say that wives and girl-friends weren't worried about their men folk serving in the forces.

Then, all of a sudden, you heard that someone was missing or, a POW. The war was suddenly brought home with a vengeance to everyone. Also, the news on the wireless and in the newspapers was very bad, although usually less so than the reality.

One of the village girls had a boy-friend who was Canadian. He had come over to Britain to volunteer and was in the RAF. He was a rear gunner in a Wellington bomber and was shot down over Germany during 1942.

For a long time there was no news of him and then Zena, her name was, heard that he was a POW. At the end of the war he returned looking under-weight but, happy and there was a big party to celebrate his return and where they got engaged! a truly happy ending.

Another memory, this time not a happy one, was the son of some friends, who was a Pilot in the Fleet Air Arm was shot down during the early part of the war and killed in action.

There was a Polish Bomber Squadron based at Abingdon and they were a mad lot and frequented a pub near to Frilford golf club called "The Dog House".

As the war wore on so the aircraft changed. Whitley and Wellingtons were replaced by Stirling's and Halifax's. finally, the main heavy bomber was the Lancaster. These used to drone over us from Abingdon and other local airfields night after night.

We also started to see a lot of Dakota's often towing Horsa gliders. In fact, several gliders came down nearby during one training exercise and one hit some power cables, luckily without major injuries to the crew.

More and more of the adult male and female villagers had disappeared into the forces and more and more replacements were needed to work the farms.

The result of all this was to put at a premium such labour as was available. This meant Land Army girls, POW's and me and my friends!

Various Army units appeared from time to time on exercises and the like.

It sounds strange now but, remember that everyone was travelling around at night with the merest glimmer of a light. Army lorries just had a small light shining on the white painted differential casing as a guide to the one behind. Cars had covers over their head-lights with two or, three small slits to let out some light.

Then there was the arrival of the Americans - I believe it would have been during 1942 that they were first sighted. They were so different to our troops - their uniforms were so much smarter and their accents were very strange to us then.

They established a tented camp just up the road from the Greyhound at Besselsleigh and naturally it became their local. This was viewed with mixed feelings by the locals as beer was in short supply and the Yanks were drinking most of it!

Their tents were like nothing we had ever seen then - They were square and big enough to stand up in without hitting the roof. They were each fitted up with a stove. Nothing at all like the British Army "Bell tents".

We all got used to seeing Jeeps and other strange vehicles on our roads, they in turn, got used to our little winding lanes and driving on the wrong side.

The Americans were very keen to get on with the locals and when invited to someone's home would usually bring all sorts of goodies such as tinned food, Nylon's for the girls and sweets for the kids. They knew that the villagers didn't have much of anything to spare at that time.

A British Tank Squadron came into the village at one time. They were on the inevitable exercise and were parked down near Bablockhythe, in the fields. We boys went down to see them and found about four or, five Cromwell (I think that was their name) Tanks parked with their crews brewing up. Naturally, the sight of all that hardware was exciting to us and we were allowed up and into the cockpit of one.

During the build up for the D day landings there were convoys going through the village day and night. There was every sort of vehicle you could possibly think of - Lorries, Troop Carriers, Bren Gun Carriers, Tanks of all shapes and sizes, Self-propelled Guns, Despatch riders and MP's to control and direct the traffic.

This almost continuous stream continued for what must have been a fortnight before it gradually quietened down to something approaching normality.

Naturally, during this time and whenever I was home from school I would walk up to the corner just below the War Memorial and watch these convoys with great interest and excitement.

There were troops of every nationality including French, Polish, Czech, Dutch, Canadians, Anzacs, Americans and so on. Obviously, the build up for the second front was beginning and something big would happen before too long!

Just before all this activity we had seen dumps of what seemed to be ammunition along local country roads and this was further evidence that the big day was getting close.

People's morale was starting to improve by this time. It had never been broken but, for three years the news had been mostly bad or, at the very least, not good and people's resistance had begun to wane a little.

North Africa had been a great victory and this coupled with the nightly bombing raids over Germany and the day raids by the Americans as well, really cheered people up and convinced them that we had turned the corner.

Everyone, including us teenager's used to sit with our ears glued to the wireless when there was a news bulletin.

People, during that wartime period in their lives, were much closer to each other than they had ever been.

Back to 1944 - The build up of men and materials continued and there was a constant stream through the village. Then a period of calm followed for a week or, so. And then came the news of the D Day landings - we all sat with our ears glued to the wireless whenever we could. For the first few days the news was fairly sparse and we didn't really know if the invasion was going to work.

After a week or, so the news began to be more positive and our hopes were raised. There were set backs and of course, there were casualties but, we were getting closer to the end of the war.

Then one Autumn morning in very misty conditions we heard lots of aircraft overhead. Through the patches of hazy sky we could discern dozens of Dakota's and the like with Gliders in tow. A few hours later they were to return with their gliders still hooked on.

Wherever they had been going to drop their tows must have been covered in the fog that had persisted most of that day over us. The result of this was gliders being released all over the place as the Dakotas prepared for landing.

A day or, so later the same "exercise" was repeated and this time the planes returned without their gliders. The battle of Arnhem had begun.

So the war continued for several months but, one could sense that the end was drawing ever closer.

The war in the Far East was to continue for several more months but, at last, the main enemy had been defeated.

How did all this affect us? In all sorts of ways - there were preparations for a General Election. The soldiers began to come home and there were frequent welcome home parties.

Food was still on ration as was petrol and clothes. So, there wasn't any sudden improvement to the rather dreary existence we had all got used to. In fact, it was a bit of an anticlimax. One of the few nice things to happen in that immediate post-war time was the return of Oranges and Bananas to the shops. We hadn't seen these for six whole years!

Basically, The United Kingdom was worn-out and broke by the war's end and to a great extent so were it's people. Our former enemies were helped by the USA to rebuild their countries and industries as also were France and the Lowlands countries but, we had to try to help ourselves for no-one else was going to.

Peter Nurse 1994

Biddulph

Contributed originally by jasstuart (BBC WW2 People's War)

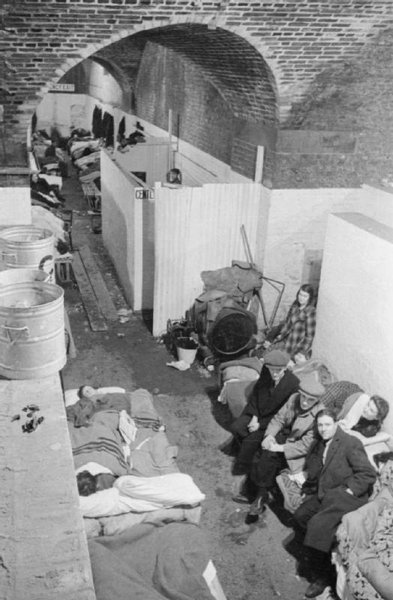

All very romantic. We think of sleep in a comfy bed, with spotless sheets, a plump pillow and a coverlet; or perhaps a Duvet. Forget it! For those who have the mileage and are able to remember the war years, read on. For those that don’t, listen to your Granddad.

We were Territorial Army lads, just returned from our yearly Camp on Beaulieu Heath, in Hampshire.

Under canvas of course and lying on the ‘good earth’, to sleep.

We lads of the 10th Battalion, Tower Hamlet Rifles; gathered together from the East End of London, in the Borough known as ‘The Tower Hamlets’.

We were ‘called up’ on the 1st September 1939. We were fully equipped, therefore we were told to take our rifles home and not to hand them back to the Armoury. We reported for duty the next day, when our ‘call up’ papers arrived by post.

Having said tearful farewells to Mums and Sweethearts; we were marched out of the Drill Hall on Tredegar Road Bow and on to Bow Road, ‘then right wheel’ into Cooper’s Company School.

We were about four hundred yards away from where we started, where our loved ones had just waved us goodbye. We were there for two whole months, sleeping in our army issue of three, ‘horse’ blankets, on the Parquet Floor.

Then we were taken to Swindon, to sleep on the dance floor of the Co-op Hall. We now had three new ‘horse type’ blankets each. They had to be folded with box-like corners and laid out neatly with knife, fork, spoon, housewife and mess-tin. Everything else, stowed away out of sight behind our kit bags.

Our webbing equipment, with bayonet and water bottle attached, spread neatly over the blankets, and army greatcoats, (if you had one), folded as per ‘regulation’, according to the Sergeant. Many of us still had Busmen’s Overcoats! Then a move to another part of the town; there to sleep on the concrete floor of a High Street garage.

Months rolled by, and we were training, training all the time, in the fine arts of a mechanised army, though sadly, we did not yet have our vehicles. We were ‘fit as fiddles’ and ‘straining at the leash’ to have a go at Hitler and his mates. But did we? No, We were sent to guard the Docks and ships on the Thames in the East End of London, and sleeping rough, among sacks of produce like raw coffee beans, along with the rodents who lived there. A few spies were captured, so we were told! We guarded the Dry Docks. Dickey Seewright fell in, fortunately there was still about ten feet of water, but a long drop.

Being in full equipment, helmet, pack, Bayonet and Rifle, plus Ammo Boots, he rolled over and over. Counter balanced, you see? We made Dickey as comfortable as we could on some dry sacking, gave him a good rub down, and then returned to our duties. Between helping the police evict unwelcome people off ships, and patrolling the Docks, we got our heads down, sometimes.

We spent most of 1940 around the Dock-land, sometimes assisting, where we could, with fire fighting.

Now we were under canvas on Hampstead Heath. At least with dry ground to sleep on, in bell-tents that had seen previous wars. And sleep? That was a laugh. Impossible with anti-aircraft guns banging away night and day, close to our Company Line’s, trying to bring down German Bombers.

We were then moved to Dunstable Bedfordshire. At the foot of a hill on Dunstable Downs, a windmill became the home for about twenty-five of us. The rest of A Company, now designated as part of the 10th Battalion the Rifle Brigade: Sixth Armoured Division: were scattered in derelict houses in the neighbourhood. Talk about ‘wherever I lay my head then that’s my home!’

During 1941 we received our vehicles. Now we charged around the country, trying to kid Hitler into thinking that we had more troops than he thought we had, and more Armoured Divisions to call on

We travelled by day and night, North, South, East and West, all over the country; with short rest periods in between, mostly when supplies and petrol were brought up. One spell of about three months, we slept under the July Stands, on the Newmarket racecourse. It was a concrete floor!

The MO’s Surgery was a stable. Most fitting we thought, for to us he seemed more like Vet.

Then we travelled to Scotland; once more under canvas, in bell-tents, leaking at the seams in the pouring ran and Scots Mist, that seemed to go on forever. We were camped by the side of a river, known to overflow its banks. Everywhere was mud. The nearest town was Stewerton in Ayrshire,

Whose people were kind to us, in spite of the mud we took with us on our infrequent visits.

At the camp we were issued with a rubber ground sheet each, which kept the blankets out of the mud;

providing you didn’t roll over in a troubled sleep. Now I was a Corporal with two stripes. Now when you are a rifleman, you have only have to worry about yourself; but as a Section Leader you have seven children to worry about. ‘See that they shave, are fed and watered, kept clean and dry, with untroubled sleep’. That’s a laugh, up to our eyebrows in mud! So we trained and trained. This time as a proper Scout Platoon in our Bren Gun Carriers, the Motor Platoons in their 15 hundred weight vehicles. All very mobile and ready to face the enemy; but the training went on until the day we were ordered to ‘up sticks’ and move out. It was now November 1942.

We sailed away on the Langibby Castle, sailing down the Clyde on a ship well loaded with troops, tanks, and all kinds of vehicles and equipment for war.

We sailed round and round in the Atlantic for a couple of days, until many other ships joined us to make up the convoy. We rolled around in the rough sea, but I was happy, for I was now a Lance Sergeant, which entitled me to share a cabin and have a bunk. It was heaven to lay where it was comfortable, on a soft surface and without draughts. We made our way steadily towards the Mediterranean and the North African Coast. But not for long, we were passing the twinkling lights of Tangiers, at dead of night, when a ‘U Boat Wolf Pack’ attacked the convoy. We copped a torpedo on the port side bow, making a hole above and below the water line that two double-deck buses could have driven through. Around us, ships were burning and exploding Water tight doors were closed, which gave us the chance to limp into Gibraltar, though the ship as well down at the bows.

At Gibraltar, we transferred on to the Lansteffan, another Castle Line ship. It was already pretty well loaded, though it still made room for a couple of thousand more troops. Our transport would have to catch us up later. We were meant to land at Algiers, it as under constant bombing raids and ‘U Boat’ attacks. The harbour in the Bay was ablaze. We finally landed at Bone; where our temporary abode was a deserted hospital, with arms and legs crammed into dustbins. We lay where we were put; on a cold but beautiful marble floor, with lovely blue tiles up the walls; though not appreciated at the time.

When our vehicles finally arrived, we set off towards the ‘war zone’ to chase the Germans out of Tunisia! Not that easy!

So now as a Lance Sergeant, I commanded three Bren Gun Carriers, three men to each Carrier, including me, as part of the Scout Platoon. As soon as we hit the area, we were in action. Skirmishing by day, foot patrolling by night. No rest, hardly any sleep, no time to use our new can openers. Though our spoons and mouths were ready to sample McConnickies solidified soup; eaten cold, straight from the can, as all our meals were. ‘I mean, come on!’ Do you think the front line Tommy had someone to cook for him? No chance! After a few days we managed to wedge in a bit of eating, a bit of resting here and there, and always a mug of tea at the first chance. Quickly brewed on a cut down petrol can filled with sand and fuelled with petrol. Quickly doused with a handful of sand, and carried, swinging

from the back of the Carrier. ‘Luxury!’

Our rations were packed in ‘three man packs’ to last three men three days. Ideal for a carrier crew.

It was full of assorted tins of food; all very plain and basic, after all there was a war on. Often we would get a tin of fifty fags to share between us, and a slab of dark chocolate sometimes, plus a packet of ‘paving slab hard’ dry biscuits. Of course, if supplies couldn’t get through to us, things had to stretch a little, but petrol was the chief need for the vehicles.

Naturally, we could usually find something to grumble about, but it didn’t do any harm and it gave vent to our frustrations. We were nipping about from one part of the battle zone to another. Being Mechanized Infantry, that was part of our job; filling in gaps, holding the line, patrols, patrols, patrols,

out there in the blue yonder! With so much driving, my driver Dusty Miller, could get very tired, so we took it in turns. With me at the controls, ahead in the dark, just catching the moonlight was a silvery concrete structure, like the model on a wedding cake. It was a bridge over a deep Wadi. That was how it looked as we approached. And then it was behind me. I too had fallen asleep, and dropped off! Just for a moment. Had we gone through that parapet, it would have been a longer drop, and probably out of this world. I didn’t tell the others, it might have worried them, though I doubt it.

Then the rains came. Troops and Vehicles of all kinds were bogged down in the clinging mud.

Wheels couldn’t turn and tracks had no grip. It was the same for Jerry.

On the outskirts of Bou Arada we dug two-man slit trenches, facing across the cold terrain towards the enemy positions at Le Keff. From those trenches, we were expected to rebuff any enemy infantry attack; though in the soaking wet, up to our ankles in mud we had little heart for it.

We splashed across that open ground on foot patrols, at night. Jerry did too, and often sent up Very Lights. We were a patrol of six men, walking on a compass bearing, in the dark. We had ‘hit the deck’

as a light burst above us. We waited for it to burn out. Out of the darkness a figure loomed. “That you Sarge?” he enquired casually. With the safety catch forward on my automatic, how I refrained from squeezing the trigger, I will never know. It was Chinner Halsey, our ‘end man’. His simple explanation

for wandering, was, ‘he just wanted to go to the Lav’. I saved my swearwords until next morning, then I let him have them good and proper! Nights in the slit trenches taught us how to sleep, standing up.

Just light sleep, you understand? Then your knees gave way and conveniently woke you up.

Once the ground was suitable to allow tanks and vehicles to move. We, as a Battalion, found ourselves once again, ‘in the thick of it’. It was at the end of January 1943,that our Platoon Commander lost his life. The Battalion was spread out over a large area and receiving supplies. Lieutenant Toms had just handed out the mail to his Section Leaders. We were walking back to our Carriers, when a lone bomber made a direct hit. We were all thrown about by the impact, and Lt Toms and the Platoon Sergeant, were hit. As often happens ‘in the field of battle’, with myself as senior, I jumped the equivalent of two ranks. Bypassing the rank of Platoon Sergeant and taking on the Platoon Commander’s job.

Not that I expressed my thoughts, though I did think, ‘Aye, aye, an officer on the cheap!’ So, worrying about others increased threefold. Not counting me; now when we got up to full strength, there would be thirty-three children and eleven Bren-Gun Carriers. The Company Commander, would be like a Boss plus a Union Rep, all wrapped up in one man, for me to answer to; similar to the ‘civvy street’ business world. When a supervisor is watched from above, and depended on from below.

So off we went again, nipping in and out, wherever we were needed. Often penetrating German defences, where American tanks could not. We in our low ‘Sardine Cans’, as the Yanks called them; could use the cover of folds in the ground, and Wadis. Backed up by the tanks of 17/21st Lancer and 16/5th, or Lothian and Border Horse in their Heavy Armoured Vehicles. We in our ‘wafer thin’ armour were more suitable for getting in and getting out, quickly. The Lancers came to our aid, when a small patrol of two carriers was testing the underbelly of the German defences near Medjes-el-bab.

It became very ‘hairy’, when Jerry brought up heavy weapons to assist his infantry; and tried to outflank us. We must have been under observation from way back, because a squadron of 17/21st tanks passed on either side of us. We had taken up a ‘hull down’ position on the crest of the hill, and were trying to hold off the advancing enemy. Thankfully we were ordered to withdraw. The infantry in our Motor Platoons, were also called upon to do all kinds of tasks. Like us, in our Scout Platoon ,’They never got bored!’ Opportunity would be a fine thing! They too lived from ‘hand to mouth’. Sleeping when they could, eating when they had the time, and keeping on, keeping on!

On the 7th of April 1943 the 1st Army, which we were part of, met up with the 8th Army, just below and South West of Sfax. Now the combined forces would push towards Tunis. Not easy, for Jerry fought tenaciously. Of course we were kept busy. It was reported that an Italian position still held out, having been bypassed. A Three-Carrier Patrol was sent to check them out. The ground was terrible, one minute sand the next rock and up and down Wadis. Below a slope and entering a cactus belt, a carrier shed a track. Corporal Sid Ferris and I went forward on foot. The remainder set up a defensive position and set to repairing the broken track. A fusillade of rifle fire pinned Sid and I down, followed by rough looking blokes in Burnooses, and firing from the hip. They pinched our boots and made us their prisoners.

At the top of the hill I heard a smart looking fellow in a natty uniform and medals, speak in French.

In my rough French I told him amid many swear words, that we were Anglais. The men on the hill were Goumiers, a formidable and vicious force of Arab soldiers under a French Officer. Our men had to withdraw; the firing missing us was making things difficult for them. Sid and I followed our carrier tracks for several miles in the dark, without weapons to defend us. They had mysteriously disappeared during capture.

I didn’t see the fall of Tunis. A German Mortar Bomb sent me, to the 95th Field Hospital in Algiers. It did me a favour really. Now I had crisp white sheets and pillow and a lady nurse, named Nurse Love. Not that there was much of that about. After about eight weeks, my wound through the biceps had recovered enough for me to rejoin my unit. I could still raise a pint, if one was offered.

The Company Commander sent a truck to pick me up and convey me to our mob, in the Vale Du Mort,

to be driven barmy by mosquito’s. Then we got an order to travel to Carthage, to Guard Winston Churchill and his wife. He was getting over a sickness.

Sad to say, on the way to Carthage on the Mediterranean coast. Corporal Sid Ferris, who was a temporary prisoner, along with me, had an accident. His carrier wandered too close to the edge of a crumbling dirt road in the dark, and turned over into a Wadi. The driver dug his way out with his bare hands. Sid lost his life. I will never forget him.

So after Africa, the next centre of operations was to be Italy. A different country, and a different kind of war. This time, amid foliage and trees where snipers hide and ambush is easier. I expect we’ll soon find out!