High Explosive Bomb at Belgrave Street

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Belgrave Street, Stepney, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, E1 4SD, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by BoyFarthing (BBC WW2 People's War)

I didn’t like to admit it, because everyone was saying how terrible it was, but all the goings on were more exciting than I’d ever imagined. Everything was changing. Some men came along and cut down all the iron railings in front of the houses in Digby Road (to make tanks they said); Boy scouts collected old aluminium saucepans (to make Spitfires); Machines came and dug huge holes in the Common right where we used to play football (to make sandbags); Everyone was given a gas mask (which I hated) that had to be carried wherever you went; An air raid shelter made from sheets of corrugated iron, was put up at the end of our garden, where the chickens used to be; Our trains were full of soldiers, waving and cheering, all going one way — towards the seaside; Silver barrage balloons floated over the rooftops; Policemen wore tin hats painted blue, with the letter P on the front; Fire engines were painted grey; At night it was pitch dark outside because of the blackout; Dad dug up most of his flower beds to plant potatoes and runner beans; And, best of all, I watched it all happening, day by day, almost on my own. That is, without all my school chums getting in the way and having to have their say. For they’d all been evacuated into the country somewhere or other, but our family were still at number 69, just as usual. For when the letters first came from our schools — the girls to go to Wales, me to Norfolk — Mum would have none of it. “Your not going anywhere” she said “We’re all staying together”. So we did. But it was never again the same as it used to be. Even though, as the weeks went by, and nothing happened, it was easy enough to forget that there was a war on at all.

Which is why, when it got to the first week of June 1940, it seemed only natural that, as usual, we went on our weeks summer holiday to Bognor Regis on the South coast, as usual. The fact that only the week before, our army had escaped from the Germans by the skin of its teeth by being ferried across the Channel from Dunkirk by almost anything that floated, was hardly remarked about. We had of course watched the endless trains rumble their way back from the direction of the seaside, silent and with the carriage blinds drawn, but that didn’t interfere with our plans. Mum and Dad had worked hard, saved hard, for their holiday and they weren’t having them upset by other people’s problems.

But for my Dad it meant a great deal more than that. During the first world war, as a young man of eighteen, he’d fought in the mud and blood of the trenches at Ypres, Passhendel and Vimy Ridge. He came back with the certain knowledge that all war is wrong. It may mean glory, fame and fortune to the handful who relish it, but for the great majority of ordinary men and their families it brings only hardship, pain and tears. His way of expressing it was to ignore it. To show the strength of his feelings by refusing to take part. Our family holiday to the very centre of the conflict, in the darkest days of our darkest hour, was one man’s public demonstration of his private beliefs

.

It started off just like any other Saturday afternoon: Dad in the garden, Mum in the kitchen, the two girls gone to the pictures, me just mucking about. Warm sunshine, clear blue skies. The air raid siren had just been sounded, but even that was normal. We’d got used to it by now. Just had to wait for the wailing and moaning to go quiet and, before you knew it, the cheerful high-pitched note of the all clear started up. But this time it didn’t. Instead, there comes the drone of aeroplane engines. Lots of them. High up. And the boom, boom, boom of anti-aircraft guns. The sound gets louder and louder until the air seems to quiver. And only then, when it seems almost overhead, can you see the tiny black dots against the deep, empty blue of the sky. Dozens and dozens of them. Neatly arranged in V shaped patterns, so high, so slow, they hardly seem to move. Then other, single dots, dropping down through them from above. The faint chatter of machine guns. A thin, black thread of smoke unravelling towards the ground. Is it one of theirs or one of ours? Clusters of tiny puffs of white, drifting along together like dandelion seeds. Then one, larger than the rest, gently parachuting towards the ground. And another. And another. Everything happening in the slowest of slow motions. Seeming to hang there in the sky, too lazy to get a move on. But still the black dots go on and on.

Dad goes off to meet the girls. Mum makes the tea. I can’t take my eyes off what’s going on. Great clouds of white and grey smoke billowing up into the sky way over beyond the school. People come out into the street to watch. The word goes round that “The poor old Docks have copped it”. By the time the sun goes down the planes have gone, the all clear sounded, and the smoke towers right across the horizon. Then as the light fades, a red fiery glow shines brighter and brighter. Even from this far away we can see it flicker and flash on the clouds above like some gigantic furnace. Everyone seems remarkably calm. As though not quite believing what they see. Then one of our neighbours, a man who always kept to himself, runs up and down the street shouting “Isleworth! Isleworth! It’s alright at Isleworth! Come on, we’ve all got to go to Isleworth! That’s where I’m going — Isleworth!” But no one takes any notice of him. And we can’t all go to Isleworth — wherever that is. Then where can we go? What can we do? And by way of an ironic answer, the siren starts it’s wailing again.

We spend that night in the shelter at the end of the garden. Listening to the crump of bombs in the distance. Thinking about the poor devils underneath it all. Among them are probably one of Dad’s close friends from work, George Nesbitt, a driver, his wife Iris, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Eileen. They live at Stepney, right by the docks. We’d once been there for tea. A block of flats with narrow stone stairs and tiny little rooms. From an iron balcony you could see over the high dock’s wall at the forest of cranes and painted funnels of the ships. Mr Nesbitt knew all about them. “ The red one with the yellow and black bands and the letter W is The West Indies Company. Came in on Wednesday with bananas, sugar, and I daresay a few crates of rum. She’s due to be loaded with flour, apples and tinned vegetables — and that one next to it…” He also knows a lot about birds. Every corner of their flat with a birdcage of chirping, flashing, brightly coloured feathers and bright, winking eyes. In the kitchen a tame parrot that coos and squawks in private conversation with Mrs Nesbitt. Eileen is a quiet girl who reads a lot and, like her mother, is quick to see the funny side of things. We’d once spent a holiday with them at Bognor. One of the best we’d ever had. Sitting here, in the chilly dankness of our shelter, it’s best not to think what might have happened to them. But difficult not to.

The next night is the same. Only worse. And the next. Ditto. We seem to have hardly slept. And it’s getting closer. More widely spread. Mum and Dad seem to take it in their stride. Unruffled by it all. Almost as though it wasn’t really happening. Anxious only to see that we’re not going cold or hungry. Then one night, after about a week of this, it suddenly landed on our doorstep.

At the end of our garden is a brick wall. On the other side, a short row of terraced houses. Then another, much higher, wall. And on the other side of that, the Berger paint factory. One of the largest in London. A place so inflammable that even the smallest fire there had always bought out the fire engines like a swarm of bees. Now the whole place is alight. Tanks exploding. Flames shooting high up in the air. Bright enough to read a newspaper if anyone was so daft. Firemen come rushing up through the garden. Rolling out hoses to train over the wall. Flattening out Dad’s delphiniums on the way. They’re astonished to find us sitting quietly sitting in our hole in the ground. “Get out!” they urge

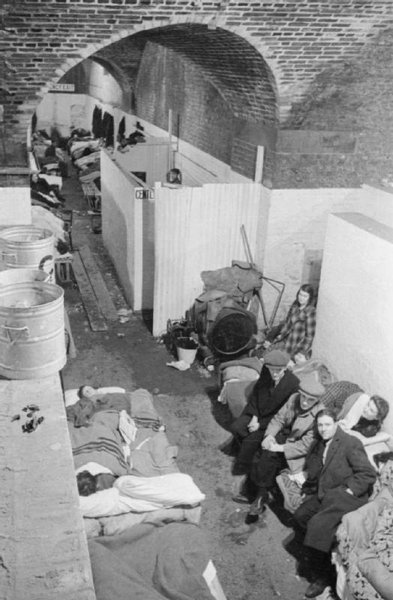

“It’s about to go up! Make a run for it!” So we all troop off, trying to look as if we’re not in a hurry, to the public shelters on Hackney Marshes. Underground trenches, dripping with moisture, crammed with people on hard wooden planks, crying, arguing, trying to doze off. It was the longest night of my life. And at first light, after the all-clear, we walk back along Homerton High Street. So sure am I that our house had been burnt to a cinder, I can hardly bear to turn the corner into Digby Road. But it’s still there! Untouched! Unbowed! Firemen and hoses all gone. Everything remarkably normal. I feel a pang of guilt at running away and leaving it to its fate all by itself. Make it a silent promise that I won’t do it again. A promise that lasts for just two more nights of the blitz.

I hear it coming from a long way off. Through the din of gunfire and the clanging of fire engine and ambulance bells, a small, piercing, screeching sound. Rapidly getting louder and louder. Rising to a shriek. Cramming itself into our tiny shelter where we crouch. Reaching a crescendo of screaming violence that vibrates inside my head. To be obliterated by something even worse. A gigantic explosion that lifts the whole shelter…the whole garden…the whole of Digby Road, a foot into the air. When the shuddering stops, and a blanket of silence comes down, Dad says, calm as you like, “That was close!”. He clambers out into the darkness. I join him. He thinks it must have been on the other side of the railway. The glue factory perhaps. Or the box factory at the end of the road. And then, in the faintest of twilights, I just make out a jagged black shape where our house used to be.

When dawn breaks, we pick our way silently over the rubble of bricks and splintered wood that once was our home. None of it means a thing. It could have been anybody’s home, anywhere. We walk away. Away from Digby Road. I never even look back. I can’t. The heavy lead weight inside of me sees to that.

Just a few days before, one of the van drivers where Dad works had handed him a piece of paper. On it was written the name and address of one of Dad’s distant cousins. Someone he hadn’t seen for years. May Pelling. She had spotted the driver delivering in her High Street and had asked if he happened to know George Houser. “Of course — everyone knows good old George!”. So she scribbles down her address, asks him to give it to him and tell him that if ever he needs help in these terrible times, to contact her. That piece of paper was in his wallet, in the shelter, the night before. One of the few things we still had to our name. The address is 102 Osidge Lane, Southgate.

What are we doing here? Why here? Where is here? It’s certainly not Isleworth - but might just as well be. The tube station we got off said ’Southgate’. Yet Dad said this is North London. Or should it be North of London? Because, going by the map of the tube line in the carriage, which I’ve been studying, Southgate is only two stops from the end of the line. It’s just about falling off the edge of London altogether! And why ‘Piccadilly Line’? This is about as far from Piccadilly as the North Pole. Perhaps that’s the reason why we’ve come. No signs of bombs here. Come to that, not much of the war at all. Not country, not town. Not a place to be evacuated to, or from. Everything new. And clean. And tidy. Ornamental trees, laden with red berries, their leaves turning gold, line the pavements. A garden in front of every house. With a gate, a path, a lawn, and flowers. Everything staked, labelled, trimmed. Nothing out of place. Except us. I’ve still got my pyjama trousers tucked into my socks. The girls are wearing raincoats and headscarves. Dad has a muffler where his clean white collar usually is. Mum’s got on her old winter coat, the one she never goes out in. And carries a tied up bundle of bits and pieces we had in the shelter. Now and again I notice people giving us a sideways glance, then looking quickly away in case you might catch their eye. Are they shocked? embarrassed? shy, even? No one seems at all interested in asking if they can help this gaggle of strangers in a strange land. Not even the road sweeper when Dad asks him the way to Osidge Lane.

The door opens. A woman’s face. Dark eyes, dark hair, rosy cheeks. Her smile checked in mid air at the sight of us on her doorstep. Intake of breath. Eyes widen with shock. Her simple words brimming with concern. “George! Nell! What’s the matter?” Mum says:” We’ve just lost everything we had” An answer hardly audible through the choking sob in her throat. Biting her lip to keep back the tears. It was the first time I’d ever seen my mother cry.

We are immediately swept inside on a wave of compassion. Kind words, helping hands, sympathy, hot food and cups of tea. Aunt May lives here with her husband, Uncle Ernie and their ten-year-old daughter, Pam. And two single ladies sheltering from the blitz. Five people in a small three-bedroom house. Now the five of us turn up, unannounced, out of the blue. With nothing but our ration books and what we are wearing. Taken in and cared for by people I’d never even seen before.

In every way Osidge Lane is different from Digby Road. Yet it is just like coming home. We are safe. They are family. For this is a Houser house.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Sporadic air-raids went on all through 1943, but as Autumn came, bringing the dark evenings with it, the "Little Blitz" started, with plenty of bombs falling in our area and I got my first real experience of NFS work.

There were Air-Raids every night, though never on the scale of 1940/41.

By now, my own School, St. Olave's, had re-opened at Tower Bridge with a skeleton staff of Masters, as about a hundred boys had returned to London.

I was glad to go back to my own school, and I no longer had to cycle all the way to Lewisham every day.

Part of the School Buildings had been taken over by the NFS as a Sub-Station for 37 Fire Area, the one next to ours, so luckily none of the Firemen knew me, and I kept quiet about my evening activities in School. I didn't think the Head would be too pleased if he found out I was an NFS Messenger.

The Air-Raids usually started in the early evening, and were mostly over by midnight.

We had a few nasty incidents in the area, but most of them were just outside our patch. If we were around though, even off-duty. Sid and I would help the Rescue Men if we could, usually forming part of the chain passing baskets of rubble down from the highly skilled diggers doing the rescue, and sometimes helping to get the walking wounded out. They were always in a state of shock, and needed comforting until the Ambulances came.

One particular incident that I can never forget makes me smile to myself and then want to cry.

One night, Sid and I were riding home from the Station. It was quiet, but the Alert was still on, as the All-Clear hadn't sounded yet.

As we neared home, Searchlights criss-crossed in the sky, there was the sound of AA-Guns and Plane engines. Then came a flash and the sound of a large explosion ahead of us towards the river, followed by the sound of receding gunfire and airplane engines. It was probably a solitary plane jettisoning it's bombs and running for home.

We instinctively rode towards the cloud of smoke visible in the moonlight in front of us.

When we got to Jamaica Road, the main road running parallel with the river, we turned towards the part known as Dockhead, on a sharp bend of the main road, just off which Dockhead Fire-Station was located.

Arrived there, we must have been among the first on the scene. There was a big hole in the road cutting off the Tram-Lines, and a loud rushing noise like an Express-Train was coming from it. The Fire-Station a few hundred yards away looked deserted. All the Appliances must have been out on call.

As we approached the crater, I realised that the sound we heard was running water, and when we joined the couple of ARP Men looking down into it, I was amazed to see by the light from the Warden's Lantern, a huge broken water-main with water pouring from it and cascading down through shattered brickwork into a sewer below.

Then we heard a shout: "Help! over here!"

On the far side of the road, right on the bend away from the river, stood an RC Convent. It was a large solid building, with very small windows facing the road, and a statue of Our Lady in a niche on the wall. It didn't look as though it had suffered very much on the outside, but the other side of the road was a different story.

The blast had gone that way, and the buildings on the main road were badly damaged.

A little to the left of the crater as we faced it was Mill Street, lined with Warehouses and Spice Mills, it led down to the River. Facing us was a terrace of small cottages at a right angle to the main road, approached by a paved walk-way. These had taken the full force of the blast, and were almost demolished. This was where the call for help had come from.

We dashed over to find a Warden by the remains of the first cottage.

"Listen!" He said. After a short silence we heard a faint sob come from the debris. Luckily for the person underneath, the blast had pushed the bulk of the wreckage away from her, and she wasn't buried very deeply.

We got to work to free her, moving the debris by hand, piece by piece, as we'd learnt that was the best way. A ceiling joist and some broken floorboards lying across her upper parts had saved her life by getting wedged and supporting the debris above.

When we'd uncovered most of her, we used a large lump of timber as a lever and held the joist up while the Warden gently eased her out.

I looked down on a young woman around eighteen or so. She was wearing a check skirt that was up over her body, showing all her legs. She was covered in dust but definitely alive. Her eyes opened, and she sat up suddenly. A look of consternation crossed her face as she saw three grimy chaps in Tin-Hats looking down on her, and she hurriedly pulled her skirt down over her knees.

I was still holding the timber, and couldn't help smiling at the Girl's first instinct being modesty. I felt embarassed, but was pleased that she seemed alright, although she was obviously in shock.

At that moment we heard the noise of activity behind us as the Rescue Squad and Ambulances arrived.

A couple of Ambulance Girls came up with a Stretcher and Blankets.

They took charge of the Young Lady while we followed the Warden and Rescue Squad to the next Cottage.

The Warden seemed to know who lived in the house, and directed the Rescue Men, who quickly got to work. We mucked in and helped, but I must confess, I wish I hadn't, for there we saw our most sickening sight of the War.

I'd already seen many dead and injured people in the Blitz, and was to see more when the Doodle-Bugs and V2 Rockets started, but nothing like this.

The Rescue Men located someone buried in the wreckage of the House. We formed our chain of baskets, and the debris round them was soon cleared.

To my horror, we'd uncovered a Woman face down over a large bowl There was a tiny Baby in the muddy water, who she must have been bathing. Both of them were dead.

We all went silent. The Rescue Men were hardened to these sights, and carried on to the next job once the Ambulance Girls came, but Sid and I made our excuses and left, I felt sick at heart, and I think Sid felt the same. We hardly said a word to each other all the way home.

I suppose that the people in those houses had thought the raid was over and left their shelter, although by now many just ignored the sirens and got on with their business, fatalistically taking a chance.

The Grand Surrey Canal ran through our district to join the Thames at Surrey Docks Basin, and the NFS had commandeered the house behind a Shop on Canal Bridge, Old Kent Road, as a Sub-Station.

We had a Fire-Barge moored on the Canal outside with four Trailer-Pumps on board.

The Barge was the powered one of a pair of "Monkey Boats" that once used to ply the Canals, carrying Goods. It had a big Thornycroft Marine-Engine.

I used to do a duty there now and again, and got to know Bob, the Leading-Fireman who was in-charge, quite well. His other job was at Barclays Brewery in Southwark.

He allowed me to go there on Sunday mornings when the Crew exercised with the Barge on the Canal.

It was certainly something different from tearing along the road on a Fire-Engine.

One day, I reported there for duty, and found that the Navy had requisitioned the engine from the Barge. I thought they must have been getting desperate, but with hindsight, I expect it was needed in the preparations for D-Day.

Apparently, the orders were that the Crew would tow the Barge along the Tow-path by hand when called out, but Bob, who was ex-Navy, had an idea.

He mounted a Swivel Hose-Nozzle on the Stern of the Barge, and one on the Bow, connecting them to one of the Pumps in the Hold. When the water was turned on at either Nozzle, a powerful jet of water was directed behind the Barge, driving it forward or backward as necessary, and Bob could steer it by using the Swivel.

This worked very well, and the Crew never had to tow the Barge by hand. It must have been the first ever Jet-Propelled Fire-Boat

We had plenty to do for a time in the "Little Blitz". The Germans dropped lots of Containers loaded with Incediary Bombs. These were known as "Molotov Breadbaskets," don't ask me why!

Each one held hundreds of Incendiaries. They were supposed to open and scatter them while dropping, but they didn't always open properly, so the bombs came down in a small area, many still in the Container, and didn't go off.

A lot of them that hit the ground properly didn't go off either, as they were sabotaged by Hitler's Slave-Labourers in the Bomb Factories at risk of death or worse to themselves if caught. Some of the detonators were wedged in off-centre, or otherwise wrongly assembled.

The little white-metal bombs were filled with magnesium powder, they were cone-shaped at the top to take a push-on fin, and had a heavy steel screw-in cap at the bottom containing the detonator, These Magnesium Bombs were wicked little things and burned with a very hot flame. I often came across a circular hole in a Pavement-Stone where one had landed upright, burnt it's way right through the stone and fizzled out in the clay underneath.

To make life a bit more hazardous for the Civil Defence Workers, Jerry had started mixing explosive Anti-Personnel Incendiaries amonst the others. Designed to catch the unwary Fire-Fighter who got too close, they could kill or maim. But were easily recogniseable in their un-detonated state, as they were slightly longer and had an extra band painted yellow.

One of these "Molotov Breadbaskets" came down in the Playground of the Paragon School, off New Kent Road, one evening. It had failed to open properly and was half-full of unexploded Incendiaries.

This School was one of our Sub-Stations, so any small fires round about were quickly dealt with.

While we were up there, Sid and I were hoping to have a look inside the Container, and perhaps get a souvenir or two, but UXB's were the responsibility of the Police, and they wouldn't let us get too near for fear of explosion, so we didn't get much of a look before the Bomb-Disposal People came and took it away.

One other macabre, but slightly humorous incident is worthy of mention.

A large Bomb had fallen close by the Borough Tube Station Booking Hall when it was busy, and there were many casualties. The lifts had crashed to the bottom so the Rescue Men had a nasty job.

On the opposite corner, stood the premises of a large Engineering Company, famous for making screws, and next door, a large Warehouse.

The roof and upper floors of this building had collapsed, but the walls were still standing.

A WVS Mobile Canteen was parked nearby, and we were enjoying a cup of tea with the Rescue Men, who'd stopped for a break, when a Steel-Helmeted Special PC came hurrying up to the Squad-Leader.

"There's bodies under the rubble in there!"

He cried, his face aghast. as he pointed to the warehouse "Hasn't anyone checked it yet?"

The Rescue Man's face broke into a broad smile.

"Keep your hair on!" He said. "There's no people in there, they all went home long before the bombs dropped. There's plenty of dead meat though, what you saw in the rubble were sides of bacon, they were all hanging from hooks in the ceiling. It's a Bacon Warehouse."

The poor old Special didn't know where to put his face. Still, he may have been a stranger to the district, and it was dark and dusty in there.

The "Little Blitz petered out in the Spring of 1944, and Raids became sporadic again.

With rumours of Hitler's Secret-Weapons around, we all awaited the next and final phase of our War, which was to begin in June, a week after D-Day, with the first of them to reach London and fall on Bethnal Green. The germans called it the V1, it was a jet-propelled pilotless flying-Bomb armed with 850kg of high-explosive, nicknamed the "Doodle-Bug".

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by brssouthglosproject (BBC WW2 People's War)

The siren sounded 'All Clear'. The wail of a siren, for those of us who heard it in wartime, was never to be forgotten. We had come up from the underground shelter. Mum, Maisie, Stella, Evelyn, Betty and me. We stood there a little dazed but thankful, the bombing had ceased, at least for now. It had been a routine we had followed many times already. First the siren warning of an impending attack, then hurrying to the nearest shelter. As the time wore on trips to the shelter were more orderly with less rush and tear. We simply had gotten more used to it, finding also, that there was generally more time between the air raid warning and bombs falling. Indeed sometimes there were no bombs and the 'all clear' sounded almost as soon as you were underground. Other times we would stay in the shelter for hours. There was never much room so people were encouraged to keep their belongings to a minimum.

It was incredible what some folk would try to take down the shelter with them. The ever, vigilant Air Raid Precaution wardens would be heard 'you can't take that now, can you luv' as some poor old dear tried to take a cage down with her budgie in it. The shelters were damp and dingy. Cold at first, they would become hot and clammy with the amount of bodies in them. The aroma far from exotic would defy separation by one's senses, a melting pot of every odour the body can emit, and sprinkled with Evening in Paris (my dad called it Midnight in Wapping) lashings of slap and peroxide as some of the ladies were wont to use. 'Well I wouldn't go down the shelter without me face on, now would I!' Us kids took little notice of the all too familiar routine. The adults did the worrying, some more than others. Our mum Elizabeth, Liz to everyone, was an exceedingly tough lady. Although under five feet tall she could square up to most with a look followed by a flying shopping bag if need be. She would make sure that we were as comfortable as possible, but she wouldn't put up with any moaning either. She was an advocate of instant retribution: a swift smack around the ear was her preferred deterrent! If by chance she had meted out the discipline to the wrong child she justified her actions by saying: 'Well, you must have done something wrong that I don't know of, so it will serve for that'. Arguing with mum was futile.

We stood in a group on a small patch of green opposite the entrance to the shelter, the five of us, and mum. The sky was black with smoke and there were fires everywhere. This time we had not been so lucky. Our street had copped it; so had Elsa Street where we were all born, it was in ruins. For the first time in her 37 years of life, our lovely mum didn't know what to do. Like the amazing woman she was, after few minutes, composed, she turned to Stella and Maisie, the two eldest, and told them to look after Eve and me. She scooped Betty up in her arms and say to us 'Wait there I will find out what's happening'. Each direction she tried to take ended with her return after a few minutes. She would say 'Don't worry kids I won't be long' and off she would go again. The whole area had been flattened. Fire hoses wriggled along the ground like snakes, as they were pulled from building to building. Fractured water mains spurted fountains of water high in the air. Emergency supplies had to be pumped from the Regent's canal. Firemen, ambulance crews, civil defence members, and the heavy rescue teams were going about their work. The smoke stung your eyes, the dust got in your mouth and the acrid smell of gas lingered in your nostrils. Civilians, those uninjured and able to help others did so.

As if a vision, dad appeared. He seemed to come from nowhere out of the smoke and dust. With a look of panic on his face he asked 'Where is your mother?' 'Its all right' said Stella. 'She has gone to find somewhere for us to go and taken Betty with her.' His relief was instant. He asked if we were all right, then touched each one of us on the head just to make sure. His face was black, his blue overalls covered in grime, under his arm he held a helmet with the letter R for rescue painted on the front. For that is what he did throughout the Blitz. Defiant, he would never go down a shelter. Mum came back with Betty in her arms. 'Liz I thought something had happened to you.' With tears in his eyes he continued 'My London's on fire. I never thought I would see this day.' Like most East-Enders, dad thought London exclusively his. He would have died for her.

We gathered up the few things we had. Little did we know at that moment, it was all we had left in the world. Then we found our way to a reception centre. This one was a church hall, which was utilised as a shelter for those families who had been bombed out and now homeless, as indeed were many such places of worship. And very glad of them we were. The largest congregation most of them had seen in a long while!

About the middle of July 1940 the German Luftwaffe started attacking our airfields in an attempt to gain air supremacy, or at least to diminish our ability to attack their invasion force poised across the Channel waiting for the order to sail. So what did the cockneys do? They went hop-picking of course. They were not going to let Hitler ruin the only holiday most of them ever had each year. 'Goin' down 'oppin' was a ritual.

We mostly went to Paddock Wood. Whitbread and Guiness had big farms there. Each family would be allocated a hut. These were made of corrugated iron, but could, with a little flair, be made quite attractive.

When it rained conditions became challenging to say the least. There is a fair amount of clay in the sub-soil of Kent, a yellowy, slimy, sticky substance. When wet it sticks to everything and builds up on the heels of your boots so that everyone is walking around on high heels. I hated this and was continually teased 'Look Jimmy's wearing high heels'.

None of us missed out spiritually during our time in the hop fields. Father Raven saw to that. An East End priest, he spent more than 40 years in the service of his parishioners, even travelling with them to Kent each year where he had his own hut, and picked from the bine.

There had been enemy aircraft in the vicinity already and bombs had fallen in the neighbouring countryside.

Dad, mum,Stella, and Maisie were picking. Evelyn and I were playing nearby, Betty was in her pram close to mum. It was mid-morning, we could hear a drone from overhead getting steadily louder. Then, there were hundreds and hundreds of black shapes, like the migration of a million blackbirds. They covered the sky, blotting out the blue. The blood drained from my dad's face. Mum said quietly, 'My god Jim, is this it?' Apart from the pulsating drone of aircraft, not a sound came from any of the hundreds of pickers in the fields. We stood, numb, looking skywards. It was Stella's distinctive voice, 'Look, look everyone, silver dots, what are they?' She had been looking into the sun, something mum forbade us to do for fear of damaging our eyes. 'Spitfires, that's what they are, Spitfire's!' shouted dad. They came out of nowhere and pounced on the enemy bombers. All hell was let loose. People scattered in every direction, bins went over and hops were trampled in the earth. Dad grabbed Betty in one arm and me in the other, 'Run kids' he shouted, and off we went to one of the many trenches that had been dug in the event of an air raid. We reached the trench in no time; Dad hurled us into it. We fell on top of each other. For good measure dad grabbed hold of an old iron bedspring that happened to be close by, and threw it over us. An enemy bomb never hit us, but the bedspring nearly brained the lot of us!

From the cover of huts and trenches, people looked skywards and witnessed what was to become known as the Battle of Britain - now commemorated each year on 15 September as being considered the decisive day of the battle. It was the most amazing sight. Planes were shot down, pilots bailed out. Enemy planes that had been hit turned for home and dropped their bomb load at random. There was devastation in the hop gardens, bomb craters appeared everywhere; amazingly very few people were badly injured. We were on the way back to see what had happened to our hut when a bomb fell nearby, and the blast threw Evelyn up against the corrugated iron cookhouse. Unconscious, she had lost one shoe and all the buttons off her dress. Dad picked her up, and much to the great relief of everyone she eventually re-gained consciousness. Apart from some bruising, she was all right. However, we were all badly shaken. Dad and mum held council with a few close friends and made the decision to return to London.

The bombing of London had began on 7 September. One of the first buildings to be hit was the Coliseum Picture Theatre, in the Mile End Road, where dad and his partner Alex had performed so many times. Being in close proximity to the docks the East End was having more than its fair share. There was bomb damage all over. We took up residence and joined those making the nightly trek to the shelters. There was a permanent pall of smoke over the city, and a red glow, so that it never looked completely dark. Whilst spirited, ever-resilient and resourceful, the Cockneys were taking a pounding; and it was showing on the faces of many. Especially the mothers of children still in London. Evacuation was not compulsory once the intensified bombing had abated, the evacuees gradually drifted back.

At the reception centre, mum was having one of her migraines. When they fell upon her they were savage. She was lying down with brown paper soaked in vinegar wrapped around her forehead. It was the only way she found to ease the pain. We had seen her like this many times before and instinctively remained quiet. Stella sat close to mum comforting her and offering to get her whatever she asked for. Commotion and confusion ruled. The comings and goings of people looking for lost loved ones, the crying, and arguments, too many demands being made on the too few voluntary helpers. After a couple of days we were told we could be evacuated once more, We didn't know where, and we didn't much care.

The train was crowded as we headed towards the West Country. The five of us and mum sat on one side of the carriage opposite another family of evacuees. Evacuees. This label would stick for years to come and would be uttered in many tones with as many meanings. A parent could stay with a child if under five. Betty was two and I three and a half. Thankfully, mum was to stay with us for the duration, It was about four hours before we got to Bristol where many of the children were to change trains for various destinations. The train pulled into Yatton station. 'Come on kids this is where we get off,' said mum. The WVS ladies in green were there, trying to organise some sense of order.

After mum's protestations that in no way were we going to be split up, she finally accepted a place offered where we could stay together as a family. Mrs Kingcott, a well-dressed lady with a warm manner, introduced herself. She told mum she would take us to a farmworkers cottage, which was standing empty and belonged to Mr Griffin. Us kids were bundled into her little Austin Seven car. We were glad to be off that draughty platform. The blackout was in force so there was very little light. We peered threough the windows trying to make out the surroundings. Up and over a bridge we entered a tiny village. Mrs Kingcott explained: 'This is Kingston Seymour'. The car stopped and out we all got, and were escorted to the front door of a small detached cottage known as Rose Cottage. Little did we know that we would remain here for the next four years.

This story is taken from extracts from Jim Ruston's book, by his request and full knowledge and kind permission, His book: A Cockney Kid In Green Wellies, published by JR Marketing, 2001 ISBN 0-9540430-0-6,

Contributed originally by peter (BBC WW2 People's War)

Setting the scene:

My Dad was the headmaster of a Junior Boys School, Attley Road, in East London, just round the corner from Bryant and Mays Match Factory.

I went to the local Infants and Junior School, "Redbridge" in Ilford, Essex

The transmission of news and public information was by the BBC Wireless, the Cinema News Reels and the National Newspapers. The whole impression, looking back, was of an extremely formal (and, as it later turned out, easily manipulated) information system.

Evacuation

The news had swung from the optimism of Munich to an increasingly pessimistic view. I sensed, even at my age of nine, that most people thought that the war with Germany would come and come soon. My reaction to all this and that of most of my compatriots was one of excitement tinged with some trepidation.

Every school in the area of greater London (and Manchester, Liverpool etc. I now know) had made plans to evacuate all children whose parents had agreed for them to so go. As my father was an Head Teacher it was decided that I with my mother as a helper would go with his school if and when the call came.

We started to prepare ourselves for what to me and thousands more children was to be the start of a great adventure. We had been issued with rectangular cardboard boxes containing our gas masks and these were mostly put into leatherette cases with a shoulder strap. We also each were to have an Haversack to hold a basic change of clothes, pyjamas, wash bag and so on.

During that late August 1939 we had a rehearsal for evacuation and every school met up in the playgrounds and were marched off to the nearest Underground Station. The next stage to one of the Main Line Stations was for the real thing only.

We each had a label firmly attached to a button-hole with our name, address and school written on. Each child had to know its group and the responsible teacher. This tryout was to prove its worth very soon.

The news was getting worse by the day. Germany then invaded Poland and it was obvious that the declaration of war was imminent.

At 11 am on Sunday the 3rd of September the Wireless announced that despite all efforts we were at war with Germany. It was, in a funny kind of way, an anticlimax.

My memory fails me as to the precise date of our evacuation. It was, I believe, a day or so before the war started, probably the 1st of September, no matter, the excitements, traumas and all those myriad experiences affecting literally millions of children and adults were about to start.

The call came. We repeated our rehearsal drill, arriving, in our case, by bus and train to Bow Road station and walking down Old Ford road to Attley Road Junior School. All the children that were coming, the teachers and helpers assembled in the play ground. Rolls were called, labels checked, haversacks and gas masks shouldered. We were off on the great adventure!

We "marched" off with great aplomb to waves and tears from fond parents who did not know when they would see their kids again, if ever.

The long snake of children and teachers arrived at Bow Road Underground Station and were shepherded down onto the platform where trains were ready and waiting.

Looking back, the organisation was fantastic. Remember, this was in the days before computers and automation! It was made possible by shear hard work and attention to detail. Tens of thousands of children were moved through the Capital transport system to the Main Line Stations in a matter of a few hours.

Our train arrived at Paddington by a somewhat roundabout route and we all disembarked making sure to stick together. We walked up to the platforms where again the groups of children were counted by their teachers. Inspectors were busily marshalling the various school groups onto awaiting trains.

We boarded our train together with several other schools. It was a dark red carriage, not, as I remember, the GWR colours, and settled ourselves down. The teachers were busy checking that nobody was missing and we then got down to eating whatever packed food we had brought with us. Many of the smaller children were beginning to miss their Mum's and the teachers and helpers had their work cut out to calm them down. Remember that most of these children had never been far from the street where they lived.

Eventually, the train got steam up and slowly moved out of the station. This would be the last time some of us would see home and London for a long time but, we were only kids and had no idea of what the future would hold. To us it was the great adventure.

The train ride seemed to go for ever! In fact we did not go that far, by mid-afternoon we arrived at Didcot.We disembarked and assembled in our groups in a wide open space at the side of the station where literally dozens of dark red Oxford buses were waiting, presumably for us.

It was at this point, according to my father, that the hitherto brilliant organisation broke down. A gaggle of Oxford Corporation Bus Inspectors descended on the assembled masses of adults and children and proceeded to embus everyone with complete disregard to School Groupings.

The buses went off in various directions ending up at village halls and the like around Oxford and what was then North Berkshire.

My father was by this time frantic that he had lost most of the children in his care (and some of the staff) and no-one seemed at all worried!

The story gets somewhat disjointed now as a combination of excitement and tiredness was rapidly replacing the adrenaline hitherto keeping this nine year old going.

Anyway, what can't be precisely remembered can be imagined! We, as mentioned, went off in this red bus to a destination unknown to all but the driver (and the inspector who wouldn't tell my Dad out of principle) - I'm sure, in retrospect, that this is when the expression "Little Hitler" was coined!!

On our bus were about fifty odd children and six or seven teachers and helpers. Most, but not all, were my dad's, but where were the rest of the two hundred or so kids he'd started out with? It was to take several days before that question was to be answered.

After some hour or, so two buses drew up together in a village and parked by a triangular green. There was a large Chestnut tree at one corner and a wooden building to one side. There was also a large crowd of people looking somewhat apprehensive.

We all picked up our haversacks and gas masks and got off the buses, marshalled by the teachers into groups and waited.

Ages of the children varied between seven and fourteen and naturally enough there were signs of incipient tears as we all wondered where we were going to end up. For me it wasn't so bad because I had Mum and Dad with me - most of them had never been separated from their families before.

A large man in a tweed suit, he turned out to be the Billeting Officer, seemed to be organising things and he kept calling out names and people stepped out from the crowd and picked a child out from our bunch. It closely resembled a cattle market!

My Father, naturally, was closely involved, monitoring the situation and trying to keep track of his charges while all this was going on.

Eventually, when it was virtually dark, everyone had been found homes in and around the village. Some brothers had been split up but, most of the kids were just glad to have somewhere to lay their heads.

While all this was happening we found out where we were; not that it meant much to me then. We were in a village called Cumnor situated in what was then North Berkshire and about four miles from Oxford.

At long last, after what seemed to me to be for ever, I was introduced to our benefactors who we were to be billeted with.They were a pleasant seeming couple of about middle age & we stayed with them for about 6 months before finding a cottage to rent.

The Village at war

It is difficult to include everything that happened during that period of my life in any precise order. Therefore, I have included the remembered instances and effects relating to the war.

The first effect was, undoubtedly, the upheaval in agriculture. Suddenly fields that had lain fallow ever since the last war were being ploughed up to grow crops. Farmers who had been struggling to make ends meet for years were actually encouraged and helped to buy new equipment to improve efficiency.

The war didn't really touch the village until the invasion of France and Dunkirk. That is, of course, not to say that wives and girl-friends weren't worried about their men folk serving in the forces.

Then, all of a sudden, you heard that someone was missing or, a POW. The war was suddenly brought home with a vengeance to everyone. Also, the news on the wireless and in the newspapers was very bad, although usually less so than the reality.

One of the village girls had a boy-friend who was Canadian. He had come over to Britain to volunteer and was in the RAF. He was a rear gunner in a Wellington bomber and was shot down over Germany during 1942.

For a long time there was no news of him and then Zena, her name was, heard that he was a POW. At the end of the war he returned looking under-weight but, happy and there was a big party to celebrate his return and where they got engaged! a truly happy ending.

Another memory, this time not a happy one, was the son of some friends, who was a Pilot in the Fleet Air Arm was shot down during the early part of the war and killed in action.

There was a Polish Bomber Squadron based at Abingdon and they were a mad lot and frequented a pub near to Frilford golf club called "The Dog House".

As the war wore on so the aircraft changed. Whitley and Wellingtons were replaced by Stirling's and Halifax's. finally, the main heavy bomber was the Lancaster. These used to drone over us from Abingdon and other local airfields night after night.

We also started to see a lot of Dakota's often towing Horsa gliders. In fact, several gliders came down nearby during one training exercise and one hit some power cables, luckily without major injuries to the crew.

More and more of the adult male and female villagers had disappeared into the forces and more and more replacements were needed to work the farms.

The result of all this was to put at a premium such labour as was available. This meant Land Army girls, POW's and me and my friends!

Various Army units appeared from time to time on exercises and the like.

It sounds strange now but, remember that everyone was travelling around at night with the merest glimmer of a light. Army lorries just had a small light shining on the white painted differential casing as a guide to the one behind. Cars had covers over their head-lights with two or, three small slits to let out some light.

Then there was the arrival of the Americans - I believe it would have been during 1942 that they were first sighted. They were so different to our troops - their uniforms were so much smarter and their accents were very strange to us then.

They established a tented camp just up the road from the Greyhound at Besselsleigh and naturally it became their local. This was viewed with mixed feelings by the locals as beer was in short supply and the Yanks were drinking most of it!

Their tents were like nothing we had ever seen then - They were square and big enough to stand up in without hitting the roof. They were each fitted up with a stove. Nothing at all like the British Army "Bell tents".

We all got used to seeing Jeeps and other strange vehicles on our roads, they in turn, got used to our little winding lanes and driving on the wrong side.

The Americans were very keen to get on with the locals and when invited to someone's home would usually bring all sorts of goodies such as tinned food, Nylon's for the girls and sweets for the kids. They knew that the villagers didn't have much of anything to spare at that time.

A British Tank Squadron came into the village at one time. They were on the inevitable exercise and were parked down near Bablockhythe, in the fields. We boys went down to see them and found about four or, five Cromwell (I think that was their name) Tanks parked with their crews brewing up. Naturally, the sight of all that hardware was exciting to us and we were allowed up and into the cockpit of one.

During the build up for the D day landings there were convoys going through the village day and night. There was every sort of vehicle you could possibly think of - Lorries, Troop Carriers, Bren Gun Carriers, Tanks of all shapes and sizes, Self-propelled Guns, Despatch riders and MP's to control and direct the traffic.

This almost continuous stream continued for what must have been a fortnight before it gradually quietened down to something approaching normality.

Naturally, during this time and whenever I was home from school I would walk up to the corner just below the War Memorial and watch these convoys with great interest and excitement.

There were troops of every nationality including French, Polish, Czech, Dutch, Canadians, Anzacs, Americans and so on. Obviously, the build up for the second front was beginning and something big would happen before too long!

Just before all this activity we had seen dumps of what seemed to be ammunition along local country roads and this was further evidence that the big day was getting close.

People's morale was starting to improve by this time. It had never been broken but, for three years the news had been mostly bad or, at the very least, not good and people's resistance had begun to wane a little.

North Africa had been a great victory and this coupled with the nightly bombing raids over Germany and the day raids by the Americans as well, really cheered people up and convinced them that we had turned the corner.

Everyone, including us teenager's used to sit with our ears glued to the wireless when there was a news bulletin.

People, during that wartime period in their lives, were much closer to each other than they had ever been.

Back to 1944 - The build up of men and materials continued and there was a constant stream through the village. Then a period of calm followed for a week or, so. And then came the news of the D Day landings - we all sat with our ears glued to the wireless whenever we could. For the first few days the news was fairly sparse and we didn't really know if the invasion was going to work.

After a week or, so the news began to be more positive and our hopes were raised. There were set backs and of course, there were casualties but, we were getting closer to the end of the war.

Then one Autumn morning in very misty conditions we heard lots of aircraft overhead. Through the patches of hazy sky we could discern dozens of Dakota's and the like with Gliders in tow. A few hours later they were to return with their gliders still hooked on.

Wherever they had been going to drop their tows must have been covered in the fog that had persisted most of that day over us. The result of this was gliders being released all over the place as the Dakotas prepared for landing.

A day or, so later the same "exercise" was repeated and this time the planes returned without their gliders. The battle of Arnhem had begun.

So the war continued for several months but, one could sense that the end was drawing ever closer.

The war in the Far East was to continue for several more months but, at last, the main enemy had been defeated.

How did all this affect us? In all sorts of ways - there were preparations for a General Election. The soldiers began to come home and there were frequent welcome home parties.

Food was still on ration as was petrol and clothes. So, there wasn't any sudden improvement to the rather dreary existence we had all got used to. In fact, it was a bit of an anticlimax. One of the few nice things to happen in that immediate post-war time was the return of Oranges and Bananas to the shops. We hadn't seen these for six whole years!

Basically, The United Kingdom was worn-out and broke by the war's end and to a great extent so were it's people. Our former enemies were helped by the USA to rebuild their countries and industries as also were France and the Lowlands countries but, we had to try to help ourselves for no-one else was going to.

Peter Nurse 1994

Biddulph

Contributed originally by lilianhenbrooks (BBC WW2 People's War)

In August 1935 my mother died of breast cancer. We lived in Dagenham at the time. She left my father, Frederick, my sister, Rose and me, Lilian. After she died we moved to Bethnal Green to be nearer family. My father was working and had found it difficult bringing us girls up by himself.

I was partially blind and went to the Daniel Street blind school but had always wanted to go to the school round the corner in Wilmot Street. My father was friendly with a lady called Ann and I knew her as Aunt Ann. She would make me tea after school. My father used to take her out a couple of times a week.

In 1939 my father and my friend, Beatty's parents, discussed sending Beatty and me to stay with Beatty's Aunty in Southport. Her surname was Chick. It was just before the start of the war and they thought it would be best for us. We packed up our things and were put on a train to Southport and told to look for the clock when we got to our destination and wait under it, where we would be picked up by Aunty, and we would recognise her because she would be wearing a brooch.

Well we got off the train and waited under the clock, as directed, which seemed to be along time, but we were determined not to move. The porter asked us in a broad Lancashire accent what we were doing. I replied, in my cockney accent, that we had been told to wait under the clock. He seemed satisfied with this and walked off. Eventually Aunty came and colected us and took us home. I went to an ordinary school in Southport then. After 7 months we returned to Bethnal Green.

We were back in London by 1940. I spent the next 2 months going to the school in Wilmot Street because troops were billeted at the blind school as the war had started by this time. This made me feel that I was the same as the other girls and I liked it there.

I was 12 years old and was about to be evacuated for the second time in June 1940. With father being at work all day it was thought best that I should go. Rose was older than me and working up town. Beatty was also older than me and had turned 14 years. She wanted to start work and wouldn't be coming along this time. A programme of evacuation had already started from London schools even though the Blitz had not begun at this time. Eventually though, many people started to return to London prematurely, thinking it was safe, only to be killed when the bombing started.

We all assembled in the school yard for 9.00 a.m. equipped with suitcase, gasmask and a numbered label on the lapel of our coats. Buses took us to King's Cross to await the trains. A few paretns did come to say goodbye and there was plenty of hugs and sobs. It was chaos at King's Cross with children and babies everywhere. Older ones in groups, babies in long prams. Officials everywhere checking numbers etc., but no one would say where we were going. It was rumourned Cornwall but no one was sure.

It was not until we reached Cardiff that we finally, after many questions, were told we were heading for Rhymney, Monmouthshire, S Wales. People didn't travel very much in those days, especially us East Enders, we thought of Wales as being another country. The thought of being so far away from home made even those that had not yet had a weep, cry. A friend of mine who was on the train, Susan Braithwaite. She had seven sisters and when she later got married in Bethnal Green all her sisters were bridesmaids. We kept in contact for a while when I moved to Leeds and then we stopped writing.

On the train also was another girl, called Phyllis, she was Jewish, she was crying and we got together for some comfort. Some of the other children were part of one family. They were saying that they were not going to be split up. Phyllis and I said that we would stick together and try to stay in the same house.

When we arrived at the station of Rhymney we were given hot cocoa drinks and biscuits by the ladies serving from trolleys on the platform and then off we set again. Two buses met us at the station to take us to a school. There we filed through a room where we were weighed, measured, examined for head lice and a spatula put over our tongues with mouths wide open and having to say "Ah"! Then into another classroom to be sorted out for accommodation. It wasn't possible for my new found friend and I to stay in the same house together, there just wasn't room but in the end we did get next door to each other.

At first I stayed with a couple called, Isaac Price and his wife and they lived in a one up one down miners cottage. They had a 16 year old daughter, called Alice. Isaac was on a regular night shift. I slept with Alice and Mrs Price slept in a single bed in an alcove of the bedroom. Before we went to bed for that first day we just had time for a snack. That first day had been a very long day. I laid in bed planning in my head, how I was going to get back to London even if I had to walk as I didn't want to stay in this strange place. People in the village were very kind and helpful and it all got better as the days went on.

The people I was staying with had another daughter who was returning home from service somewhere down South. There would be no room for me in the small house. Mrs Price's brother, Will, who was a widower, was getting married again very soon. It was arranged that I would move in with them straight after the wedding.

I moved in with them and they lived in a two bedroomed end terrace house with a back garden. I had a bedroom to myself and was so well looked after as if I was their own daughter. They had no family and I called them Uncle Will and Aunt Sally. He was a Baptist and she was a Congregationalist. They both carried on going to their respective churches. They went to church 3 times a day on a Sunday.

I used to go to Sunday school in the morning and then again with Aunt Sally and found myself singing in the choir with Aunt Sally. They had such lovely voices. There was also other things that I did at the Chapel during the week so my time was kep occupied.

One memorable Sunday there wasa terrific thunderstorm and we just couldn't leave the house for evening chapel. Hailstones thundered down like mothballs and lightening struck chimneys and roofs. We being the top house of the sloping street just had a couple of inches inside the house but below in the village centre hailstones were up to your waise and the mud washed down from the mountains ruined lots of homes. It was as bas as being bombed.

Saturday was the time to help out with the housework and I got 9d. and taken to the local cinema for the first house performance.

We went to school in a disused chapel and had equipment sent from London. We were separated from the Welsh children because of this and only came in contact with them after school when we met them in the street and played with them. We had been accompanied down to Wales by our own teachers, Mrs Meals and Miss Long. All ages joined in with all the lessons and we had good PE and both sexes played cricket and rounders etc., in the local park. Later our teachers had to go back to London and a Welshman took over. He went into the RAF later on.

When we were first evacuated some women and mothers came with us to Wales but later returned to London with their youngest children leaving the oldest in Wales.It was heard later that some of the families had been killed in the Blitz.

In December, 1940, my father died of pneumonia. A letter arrived for Mr & Mrs Price and my Uncle Will had to tell me

the bad news. He told me my father had gone to Jesus. I was in shock and couldn't believe it as I was very upset. I hadn't seen my father all the time I was in Wales, I loved my father. I yelled at him 'there is no Jesus'. I was bit hysterical and he slapped my face to calm me down.

I stayed for a further 6 months in Wales. I was in Rhymney about 18 months in all. My stay in Rhymney on the whole was a happy one and I was very fortunate to have such lovely people looking after me.

During the time I was in Wales my sister, Roase, had met her fiancee. He went through the awful experience of being at Dunkirk. He came from Leeds, West Yorkshire. Rose had met his family and had written to me to tell me about them and how they were willing to take me so that we could be together. They were also willing to look after Queenie, our Yorkshire Terrier. So later on in 1941 Rose took charge of me and came to collect me to take me to Leeds and I had to say farewell to my new found family in Rhymney. I eventually

settled down in Leeds where I made my home and had my own family, this being another story.