High Explosive Bomb at Burdett Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Burdett Road, Poplar, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, E14 7HA, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by BoyFarthing (BBC WW2 People's War)

I didn’t like to admit it, because everyone was saying how terrible it was, but all the goings on were more exciting than I’d ever imagined. Everything was changing. Some men came along and cut down all the iron railings in front of the houses in Digby Road (to make tanks they said); Boy scouts collected old aluminium saucepans (to make Spitfires); Machines came and dug huge holes in the Common right where we used to play football (to make sandbags); Everyone was given a gas mask (which I hated) that had to be carried wherever you went; An air raid shelter made from sheets of corrugated iron, was put up at the end of our garden, where the chickens used to be; Our trains were full of soldiers, waving and cheering, all going one way — towards the seaside; Silver barrage balloons floated over the rooftops; Policemen wore tin hats painted blue, with the letter P on the front; Fire engines were painted grey; At night it was pitch dark outside because of the blackout; Dad dug up most of his flower beds to plant potatoes and runner beans; And, best of all, I watched it all happening, day by day, almost on my own. That is, without all my school chums getting in the way and having to have their say. For they’d all been evacuated into the country somewhere or other, but our family were still at number 69, just as usual. For when the letters first came from our schools — the girls to go to Wales, me to Norfolk — Mum would have none of it. “Your not going anywhere” she said “We’re all staying together”. So we did. But it was never again the same as it used to be. Even though, as the weeks went by, and nothing happened, it was easy enough to forget that there was a war on at all.

Which is why, when it got to the first week of June 1940, it seemed only natural that, as usual, we went on our weeks summer holiday to Bognor Regis on the South coast, as usual. The fact that only the week before, our army had escaped from the Germans by the skin of its teeth by being ferried across the Channel from Dunkirk by almost anything that floated, was hardly remarked about. We had of course watched the endless trains rumble their way back from the direction of the seaside, silent and with the carriage blinds drawn, but that didn’t interfere with our plans. Mum and Dad had worked hard, saved hard, for their holiday and they weren’t having them upset by other people’s problems.

But for my Dad it meant a great deal more than that. During the first world war, as a young man of eighteen, he’d fought in the mud and blood of the trenches at Ypres, Passhendel and Vimy Ridge. He came back with the certain knowledge that all war is wrong. It may mean glory, fame and fortune to the handful who relish it, but for the great majority of ordinary men and their families it brings only hardship, pain and tears. His way of expressing it was to ignore it. To show the strength of his feelings by refusing to take part. Our family holiday to the very centre of the conflict, in the darkest days of our darkest hour, was one man’s public demonstration of his private beliefs

.

It started off just like any other Saturday afternoon: Dad in the garden, Mum in the kitchen, the two girls gone to the pictures, me just mucking about. Warm sunshine, clear blue skies. The air raid siren had just been sounded, but even that was normal. We’d got used to it by now. Just had to wait for the wailing and moaning to go quiet and, before you knew it, the cheerful high-pitched note of the all clear started up. But this time it didn’t. Instead, there comes the drone of aeroplane engines. Lots of them. High up. And the boom, boom, boom of anti-aircraft guns. The sound gets louder and louder until the air seems to quiver. And only then, when it seems almost overhead, can you see the tiny black dots against the deep, empty blue of the sky. Dozens and dozens of them. Neatly arranged in V shaped patterns, so high, so slow, they hardly seem to move. Then other, single dots, dropping down through them from above. The faint chatter of machine guns. A thin, black thread of smoke unravelling towards the ground. Is it one of theirs or one of ours? Clusters of tiny puffs of white, drifting along together like dandelion seeds. Then one, larger than the rest, gently parachuting towards the ground. And another. And another. Everything happening in the slowest of slow motions. Seeming to hang there in the sky, too lazy to get a move on. But still the black dots go on and on.

Dad goes off to meet the girls. Mum makes the tea. I can’t take my eyes off what’s going on. Great clouds of white and grey smoke billowing up into the sky way over beyond the school. People come out into the street to watch. The word goes round that “The poor old Docks have copped it”. By the time the sun goes down the planes have gone, the all clear sounded, and the smoke towers right across the horizon. Then as the light fades, a red fiery glow shines brighter and brighter. Even from this far away we can see it flicker and flash on the clouds above like some gigantic furnace. Everyone seems remarkably calm. As though not quite believing what they see. Then one of our neighbours, a man who always kept to himself, runs up and down the street shouting “Isleworth! Isleworth! It’s alright at Isleworth! Come on, we’ve all got to go to Isleworth! That’s where I’m going — Isleworth!” But no one takes any notice of him. And we can’t all go to Isleworth — wherever that is. Then where can we go? What can we do? And by way of an ironic answer, the siren starts it’s wailing again.

We spend that night in the shelter at the end of the garden. Listening to the crump of bombs in the distance. Thinking about the poor devils underneath it all. Among them are probably one of Dad’s close friends from work, George Nesbitt, a driver, his wife Iris, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Eileen. They live at Stepney, right by the docks. We’d once been there for tea. A block of flats with narrow stone stairs and tiny little rooms. From an iron balcony you could see over the high dock’s wall at the forest of cranes and painted funnels of the ships. Mr Nesbitt knew all about them. “ The red one with the yellow and black bands and the letter W is The West Indies Company. Came in on Wednesday with bananas, sugar, and I daresay a few crates of rum. She’s due to be loaded with flour, apples and tinned vegetables — and that one next to it…” He also knows a lot about birds. Every corner of their flat with a birdcage of chirping, flashing, brightly coloured feathers and bright, winking eyes. In the kitchen a tame parrot that coos and squawks in private conversation with Mrs Nesbitt. Eileen is a quiet girl who reads a lot and, like her mother, is quick to see the funny side of things. We’d once spent a holiday with them at Bognor. One of the best we’d ever had. Sitting here, in the chilly dankness of our shelter, it’s best not to think what might have happened to them. But difficult not to.

The next night is the same. Only worse. And the next. Ditto. We seem to have hardly slept. And it’s getting closer. More widely spread. Mum and Dad seem to take it in their stride. Unruffled by it all. Almost as though it wasn’t really happening. Anxious only to see that we’re not going cold or hungry. Then one night, after about a week of this, it suddenly landed on our doorstep.

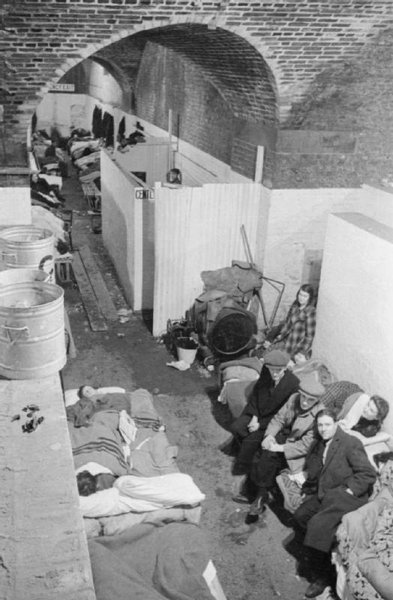

At the end of our garden is a brick wall. On the other side, a short row of terraced houses. Then another, much higher, wall. And on the other side of that, the Berger paint factory. One of the largest in London. A place so inflammable that even the smallest fire there had always bought out the fire engines like a swarm of bees. Now the whole place is alight. Tanks exploding. Flames shooting high up in the air. Bright enough to read a newspaper if anyone was so daft. Firemen come rushing up through the garden. Rolling out hoses to train over the wall. Flattening out Dad’s delphiniums on the way. They’re astonished to find us sitting quietly sitting in our hole in the ground. “Get out!” they urge

“It’s about to go up! Make a run for it!” So we all troop off, trying to look as if we’re not in a hurry, to the public shelters on Hackney Marshes. Underground trenches, dripping with moisture, crammed with people on hard wooden planks, crying, arguing, trying to doze off. It was the longest night of my life. And at first light, after the all-clear, we walk back along Homerton High Street. So sure am I that our house had been burnt to a cinder, I can hardly bear to turn the corner into Digby Road. But it’s still there! Untouched! Unbowed! Firemen and hoses all gone. Everything remarkably normal. I feel a pang of guilt at running away and leaving it to its fate all by itself. Make it a silent promise that I won’t do it again. A promise that lasts for just two more nights of the blitz.

I hear it coming from a long way off. Through the din of gunfire and the clanging of fire engine and ambulance bells, a small, piercing, screeching sound. Rapidly getting louder and louder. Rising to a shriek. Cramming itself into our tiny shelter where we crouch. Reaching a crescendo of screaming violence that vibrates inside my head. To be obliterated by something even worse. A gigantic explosion that lifts the whole shelter…the whole garden…the whole of Digby Road, a foot into the air. When the shuddering stops, and a blanket of silence comes down, Dad says, calm as you like, “That was close!”. He clambers out into the darkness. I join him. He thinks it must have been on the other side of the railway. The glue factory perhaps. Or the box factory at the end of the road. And then, in the faintest of twilights, I just make out a jagged black shape where our house used to be.

When dawn breaks, we pick our way silently over the rubble of bricks and splintered wood that once was our home. None of it means a thing. It could have been anybody’s home, anywhere. We walk away. Away from Digby Road. I never even look back. I can’t. The heavy lead weight inside of me sees to that.

Just a few days before, one of the van drivers where Dad works had handed him a piece of paper. On it was written the name and address of one of Dad’s distant cousins. Someone he hadn’t seen for years. May Pelling. She had spotted the driver delivering in her High Street and had asked if he happened to know George Houser. “Of course — everyone knows good old George!”. So she scribbles down her address, asks him to give it to him and tell him that if ever he needs help in these terrible times, to contact her. That piece of paper was in his wallet, in the shelter, the night before. One of the few things we still had to our name. The address is 102 Osidge Lane, Southgate.

What are we doing here? Why here? Where is here? It’s certainly not Isleworth - but might just as well be. The tube station we got off said ’Southgate’. Yet Dad said this is North London. Or should it be North of London? Because, going by the map of the tube line in the carriage, which I’ve been studying, Southgate is only two stops from the end of the line. It’s just about falling off the edge of London altogether! And why ‘Piccadilly Line’? This is about as far from Piccadilly as the North Pole. Perhaps that’s the reason why we’ve come. No signs of bombs here. Come to that, not much of the war at all. Not country, not town. Not a place to be evacuated to, or from. Everything new. And clean. And tidy. Ornamental trees, laden with red berries, their leaves turning gold, line the pavements. A garden in front of every house. With a gate, a path, a lawn, and flowers. Everything staked, labelled, trimmed. Nothing out of place. Except us. I’ve still got my pyjama trousers tucked into my socks. The girls are wearing raincoats and headscarves. Dad has a muffler where his clean white collar usually is. Mum’s got on her old winter coat, the one she never goes out in. And carries a tied up bundle of bits and pieces we had in the shelter. Now and again I notice people giving us a sideways glance, then looking quickly away in case you might catch their eye. Are they shocked? embarrassed? shy, even? No one seems at all interested in asking if they can help this gaggle of strangers in a strange land. Not even the road sweeper when Dad asks him the way to Osidge Lane.

The door opens. A woman’s face. Dark eyes, dark hair, rosy cheeks. Her smile checked in mid air at the sight of us on her doorstep. Intake of breath. Eyes widen with shock. Her simple words brimming with concern. “George! Nell! What’s the matter?” Mum says:” We’ve just lost everything we had” An answer hardly audible through the choking sob in her throat. Biting her lip to keep back the tears. It was the first time I’d ever seen my mother cry.

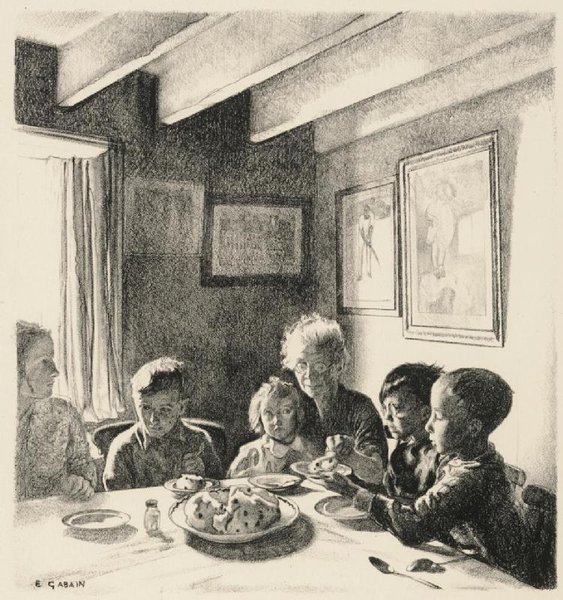

We are immediately swept inside on a wave of compassion. Kind words, helping hands, sympathy, hot food and cups of tea. Aunt May lives here with her husband, Uncle Ernie and their ten-year-old daughter, Pam. And two single ladies sheltering from the blitz. Five people in a small three-bedroom house. Now the five of us turn up, unannounced, out of the blue. With nothing but our ration books and what we are wearing. Taken in and cared for by people I’d never even seen before.

In every way Osidge Lane is different from Digby Road. Yet it is just like coming home. We are safe. They are family. For this is a Houser house.

Contributed originally by angaval (BBC WW2 People's War)

It is September 1940 and I am returning from Chrisp Street Market with my mother. I'm nearly seven and I've come back to London after being evacuated to Glastonbury during the 'phoney war'. It's a lovely warm evening and my mum is anxious to get back home with her shopping.

As we begin to turn into Brunswick Road, we hear the sound of gunfire - not unusual, as we live near the East India Docks and there is frequent gunnery practice. But then we hear the planes and the air raid sirens. ARP wardens are running about blowing whistles, shouting, 'Take cover, take cover!' We start running the last few yards home.

My dad is panicking and my nana (who speaks little English) is hysterical. We then all bolt into the Anderson shelter in the back yard, just as the first bombs start exploding. My Dad hates the Anderson as it's always full of spiders and he's scared of them. The noise is horrendous. Every time a bomb falls near, everything shakes. Above us there is the 'voom, voom, voom' sound of the planes. The ack-ack guns make a hollow booming noise and the Bofors make a rapid staccato rattle. It seems to go on for hours and then, suddenly, there is a pause, then the 'all clear'.

Stunned by the noise, we emerge. The house is still standing and doesn't seem damaged. We go out through the front door to see a scene which even now I recall as vividly as when it happened. The entire street is choked with emergency vehicles - ambulances, fire engines - all clanging their bells. The gutters and pavements are full of writhing hoses like giant snakes, and above... the sky. The sky - to the south, still a deep, beautiful blue, but to the north a vision of hell. It is red, it is orange, it is luminous yellow. It writhes in billows, it is threaded through with wisps and clouds of grey smoke and white steam. All around there are shouts and occasional screams, whistles blow and bells clang.

The neighbours stand around in small groups. They talk quietly and seem as dazed as us. Apparently most of the flames are from the Lloyd Loom factory down the road, which has taken a direct hit. The gutters run with water, soot and oily rainbows and the reflections of the fiery sky. Our respite does not last long. About 20 minutes later, another alert, we are back in the Anderson, and it all begins again.

The noise makes my knees hurt. When I tell my mother, she laughs and says it's growing pains. Maybe, maybe, but for the rest of the war; whenever there was a raid my knees always ached!

Contributed originally by peter (BBC WW2 People's War)

Setting the scene:

My Dad was the headmaster of a Junior Boys School, Attley Road, in East London, just round the corner from Bryant and Mays Match Factory.

I went to the local Infants and Junior School, "Redbridge" in Ilford, Essex

The transmission of news and public information was by the BBC Wireless, the Cinema News Reels and the National Newspapers. The whole impression, looking back, was of an extremely formal (and, as it later turned out, easily manipulated) information system.

Evacuation

The news had swung from the optimism of Munich to an increasingly pessimistic view. I sensed, even at my age of nine, that most people thought that the war with Germany would come and come soon. My reaction to all this and that of most of my compatriots was one of excitement tinged with some trepidation.

Every school in the area of greater London (and Manchester, Liverpool etc. I now know) had made plans to evacuate all children whose parents had agreed for them to so go. As my father was an Head Teacher it was decided that I with my mother as a helper would go with his school if and when the call came.

We started to prepare ourselves for what to me and thousands more children was to be the start of a great adventure. We had been issued with rectangular cardboard boxes containing our gas masks and these were mostly put into leatherette cases with a shoulder strap. We also each were to have an Haversack to hold a basic change of clothes, pyjamas, wash bag and so on.

During that late August 1939 we had a rehearsal for evacuation and every school met up in the playgrounds and were marched off to the nearest Underground Station. The next stage to one of the Main Line Stations was for the real thing only.

We each had a label firmly attached to a button-hole with our name, address and school written on. Each child had to know its group and the responsible teacher. This tryout was to prove its worth very soon.

The news was getting worse by the day. Germany then invaded Poland and it was obvious that the declaration of war was imminent.

At 11 am on Sunday the 3rd of September the Wireless announced that despite all efforts we were at war with Germany. It was, in a funny kind of way, an anticlimax.

My memory fails me as to the precise date of our evacuation. It was, I believe, a day or so before the war started, probably the 1st of September, no matter, the excitements, traumas and all those myriad experiences affecting literally millions of children and adults were about to start.

The call came. We repeated our rehearsal drill, arriving, in our case, by bus and train to Bow Road station and walking down Old Ford road to Attley Road Junior School. All the children that were coming, the teachers and helpers assembled in the play ground. Rolls were called, labels checked, haversacks and gas masks shouldered. We were off on the great adventure!

We "marched" off with great aplomb to waves and tears from fond parents who did not know when they would see their kids again, if ever.

The long snake of children and teachers arrived at Bow Road Underground Station and were shepherded down onto the platform where trains were ready and waiting.

Looking back, the organisation was fantastic. Remember, this was in the days before computers and automation! It was made possible by shear hard work and attention to detail. Tens of thousands of children were moved through the Capital transport system to the Main Line Stations in a matter of a few hours.

Our train arrived at Paddington by a somewhat roundabout route and we all disembarked making sure to stick together. We walked up to the platforms where again the groups of children were counted by their teachers. Inspectors were busily marshalling the various school groups onto awaiting trains.

We boarded our train together with several other schools. It was a dark red carriage, not, as I remember, the GWR colours, and settled ourselves down. The teachers were busy checking that nobody was missing and we then got down to eating whatever packed food we had brought with us. Many of the smaller children were beginning to miss their Mum's and the teachers and helpers had their work cut out to calm them down. Remember that most of these children had never been far from the street where they lived.

Eventually, the train got steam up and slowly moved out of the station. This would be the last time some of us would see home and London for a long time but, we were only kids and had no idea of what the future would hold. To us it was the great adventure.

The train ride seemed to go for ever! In fact we did not go that far, by mid-afternoon we arrived at Didcot.We disembarked and assembled in our groups in a wide open space at the side of the station where literally dozens of dark red Oxford buses were waiting, presumably for us.

It was at this point, according to my father, that the hitherto brilliant organisation broke down. A gaggle of Oxford Corporation Bus Inspectors descended on the assembled masses of adults and children and proceeded to embus everyone with complete disregard to School Groupings.

The buses went off in various directions ending up at village halls and the like around Oxford and what was then North Berkshire.

My father was by this time frantic that he had lost most of the children in his care (and some of the staff) and no-one seemed at all worried!

The story gets somewhat disjointed now as a combination of excitement and tiredness was rapidly replacing the adrenaline hitherto keeping this nine year old going.

Anyway, what can't be precisely remembered can be imagined! We, as mentioned, went off in this red bus to a destination unknown to all but the driver (and the inspector who wouldn't tell my Dad out of principle) - I'm sure, in retrospect, that this is when the expression "Little Hitler" was coined!!

On our bus were about fifty odd children and six or seven teachers and helpers. Most, but not all, were my dad's, but where were the rest of the two hundred or so kids he'd started out with? It was to take several days before that question was to be answered.

After some hour or, so two buses drew up together in a village and parked by a triangular green. There was a large Chestnut tree at one corner and a wooden building to one side. There was also a large crowd of people looking somewhat apprehensive.

We all picked up our haversacks and gas masks and got off the buses, marshalled by the teachers into groups and waited.

Ages of the children varied between seven and fourteen and naturally enough there were signs of incipient tears as we all wondered where we were going to end up. For me it wasn't so bad because I had Mum and Dad with me - most of them had never been separated from their families before.

A large man in a tweed suit, he turned out to be the Billeting Officer, seemed to be organising things and he kept calling out names and people stepped out from the crowd and picked a child out from our bunch. It closely resembled a cattle market!

My Father, naturally, was closely involved, monitoring the situation and trying to keep track of his charges while all this was going on.

Eventually, when it was virtually dark, everyone had been found homes in and around the village. Some brothers had been split up but, most of the kids were just glad to have somewhere to lay their heads.

While all this was happening we found out where we were; not that it meant much to me then. We were in a village called Cumnor situated in what was then North Berkshire and about four miles from Oxford.

At long last, after what seemed to me to be for ever, I was introduced to our benefactors who we were to be billeted with.They were a pleasant seeming couple of about middle age & we stayed with them for about 6 months before finding a cottage to rent.

The Village at war

It is difficult to include everything that happened during that period of my life in any precise order. Therefore, I have included the remembered instances and effects relating to the war.

The first effect was, undoubtedly, the upheaval in agriculture. Suddenly fields that had lain fallow ever since the last war were being ploughed up to grow crops. Farmers who had been struggling to make ends meet for years were actually encouraged and helped to buy new equipment to improve efficiency.

The war didn't really touch the village until the invasion of France and Dunkirk. That is, of course, not to say that wives and girl-friends weren't worried about their men folk serving in the forces.

Then, all of a sudden, you heard that someone was missing or, a POW. The war was suddenly brought home with a vengeance to everyone. Also, the news on the wireless and in the newspapers was very bad, although usually less so than the reality.

One of the village girls had a boy-friend who was Canadian. He had come over to Britain to volunteer and was in the RAF. He was a rear gunner in a Wellington bomber and was shot down over Germany during 1942.

For a long time there was no news of him and then Zena, her name was, heard that he was a POW. At the end of the war he returned looking under-weight but, happy and there was a big party to celebrate his return and where they got engaged! a truly happy ending.

Another memory, this time not a happy one, was the son of some friends, who was a Pilot in the Fleet Air Arm was shot down during the early part of the war and killed in action.

There was a Polish Bomber Squadron based at Abingdon and they were a mad lot and frequented a pub near to Frilford golf club called "The Dog House".

As the war wore on so the aircraft changed. Whitley and Wellingtons were replaced by Stirling's and Halifax's. finally, the main heavy bomber was the Lancaster. These used to drone over us from Abingdon and other local airfields night after night.

We also started to see a lot of Dakota's often towing Horsa gliders. In fact, several gliders came down nearby during one training exercise and one hit some power cables, luckily without major injuries to the crew.

More and more of the adult male and female villagers had disappeared into the forces and more and more replacements were needed to work the farms.

The result of all this was to put at a premium such labour as was available. This meant Land Army girls, POW's and me and my friends!

Various Army units appeared from time to time on exercises and the like.

It sounds strange now but, remember that everyone was travelling around at night with the merest glimmer of a light. Army lorries just had a small light shining on the white painted differential casing as a guide to the one behind. Cars had covers over their head-lights with two or, three small slits to let out some light.

Then there was the arrival of the Americans - I believe it would have been during 1942 that they were first sighted. They were so different to our troops - their uniforms were so much smarter and their accents were very strange to us then.

They established a tented camp just up the road from the Greyhound at Besselsleigh and naturally it became their local. This was viewed with mixed feelings by the locals as beer was in short supply and the Yanks were drinking most of it!

Their tents were like nothing we had ever seen then - They were square and big enough to stand up in without hitting the roof. They were each fitted up with a stove. Nothing at all like the British Army "Bell tents".

We all got used to seeing Jeeps and other strange vehicles on our roads, they in turn, got used to our little winding lanes and driving on the wrong side.

The Americans were very keen to get on with the locals and when invited to someone's home would usually bring all sorts of goodies such as tinned food, Nylon's for the girls and sweets for the kids. They knew that the villagers didn't have much of anything to spare at that time.

A British Tank Squadron came into the village at one time. They were on the inevitable exercise and were parked down near Bablockhythe, in the fields. We boys went down to see them and found about four or, five Cromwell (I think that was their name) Tanks parked with their crews brewing up. Naturally, the sight of all that hardware was exciting to us and we were allowed up and into the cockpit of one.

During the build up for the D day landings there were convoys going through the village day and night. There was every sort of vehicle you could possibly think of - Lorries, Troop Carriers, Bren Gun Carriers, Tanks of all shapes and sizes, Self-propelled Guns, Despatch riders and MP's to control and direct the traffic.

This almost continuous stream continued for what must have been a fortnight before it gradually quietened down to something approaching normality.

Naturally, during this time and whenever I was home from school I would walk up to the corner just below the War Memorial and watch these convoys with great interest and excitement.

There were troops of every nationality including French, Polish, Czech, Dutch, Canadians, Anzacs, Americans and so on. Obviously, the build up for the second front was beginning and something big would happen before too long!

Just before all this activity we had seen dumps of what seemed to be ammunition along local country roads and this was further evidence that the big day was getting close.

People's morale was starting to improve by this time. It had never been broken but, for three years the news had been mostly bad or, at the very least, not good and people's resistance had begun to wane a little.

North Africa had been a great victory and this coupled with the nightly bombing raids over Germany and the day raids by the Americans as well, really cheered people up and convinced them that we had turned the corner.

Everyone, including us teenager's used to sit with our ears glued to the wireless when there was a news bulletin.

People, during that wartime period in their lives, were much closer to each other than they had ever been.

Back to 1944 - The build up of men and materials continued and there was a constant stream through the village. Then a period of calm followed for a week or, so. And then came the news of the D Day landings - we all sat with our ears glued to the wireless whenever we could. For the first few days the news was fairly sparse and we didn't really know if the invasion was going to work.

After a week or, so the news began to be more positive and our hopes were raised. There were set backs and of course, there were casualties but, we were getting closer to the end of the war.

Then one Autumn morning in very misty conditions we heard lots of aircraft overhead. Through the patches of hazy sky we could discern dozens of Dakota's and the like with Gliders in tow. A few hours later they were to return with their gliders still hooked on.

Wherever they had been going to drop their tows must have been covered in the fog that had persisted most of that day over us. The result of this was gliders being released all over the place as the Dakotas prepared for landing.

A day or, so later the same "exercise" was repeated and this time the planes returned without their gliders. The battle of Arnhem had begun.

So the war continued for several months but, one could sense that the end was drawing ever closer.

The war in the Far East was to continue for several more months but, at last, the main enemy had been defeated.

How did all this affect us? In all sorts of ways - there were preparations for a General Election. The soldiers began to come home and there were frequent welcome home parties.

Food was still on ration as was petrol and clothes. So, there wasn't any sudden improvement to the rather dreary existence we had all got used to. In fact, it was a bit of an anticlimax. One of the few nice things to happen in that immediate post-war time was the return of Oranges and Bananas to the shops. We hadn't seen these for six whole years!

Basically, The United Kingdom was worn-out and broke by the war's end and to a great extent so were it's people. Our former enemies were helped by the USA to rebuild their countries and industries as also were France and the Lowlands countries but, we had to try to help ourselves for no-one else was going to.

Peter Nurse 1994

Biddulph

Contributed originally by Leicestershire Library Services - Countesthorpe Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jim Humphreys. He fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

TOPICS

1 EVACUATION

2 CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

3 FATHERS ROLE

4 SHELTERS

5 V.WEAPONS

THESE ARE TO BE FOUND IN SEPARATE ENTRY UNDER 'JIM HUMPHREYS - PART 2 OF 2'

1 EVACUATION

I was born in South London in October 1935 to the sound of Bow Bells. In 1938 my parents, younger sister and myself moved to Grosvenor Terrace, Camberwell, and lived there until the 1960s. Soon after war was declared we were evacuated to an area 10 miles from Swansea.

I have no recollection as to how we arrived there, all that I remember is that we were standing outside a café, together with my family, my mother's mother and 3 of her children plus about 3 suitcases. Next to the café was the local bus terminal to Swansea.

The garden had some vegetables. Grandmother was advised to make bread as there was no guarantee that the deliveryman would appear at a regular time.

To get to school we sometimes had a bus; more often we had to walk through the woods. We later experienced some rumbles and bangs during the night. We, the children, were told that it was nothing to worry about. We later discovered that after the bangs etc., a certain area of the sky was always a reddish colour. We were told by our older school friends that Swansea had been bombed again.

Not far from the bus terminal was a steep cliff edge with a path down to the sandy beach. To get to the sea we had to climb over some rocks and sometimes on these rocks and at the water's edge was this thick black sticky stuff. Once on your clothes it was very difficult to remove. We later learned that this was crude oil from ships in the channel.

An uncle and aunt, who were too old for the junior school that I attended, managed to get a job at the local farm. I have no recollection of coming back to London, but we apparently had been away for about 6 months.

Our second evacuation was to Leicester. I can remember going to the junior school along our street with my mother, two sisters and father. Father carried a suitcase and I had a parcel tied to my belt and wrist, and of course my gasmask around my neck. All the children had a luggage label tied to a buttonhole or some place where it could be seen. We were marched with a lot of other families to the main road where we waited for trams. The trams came in a long line and when our names were called, we had to get onto a certain tram. Dad did not get on. After having our names checked, some families got on and others got off.

At last we were away. There was lots of crying by the mums and children including mine. I dont remember me crying though. We ended up in Leicester station. We were asked every time a train was due, "once again in case you fall, please keep against the wall". We were there for ages; trains were arriving; some families got on and some got off. Eventually we were lead to a line of busses. After a lot of checking names again we set off. I know we ended up at a school in Earl Shilton. We were given blankets, pillows and told that there were mattresses where we would sleep.

It was here I experienced my first shower. We used to stand under the shower and get wet, then we soaped our stomachs and chest, lay on the floor against the wall and pushed off with both feet skidding across the width of the shower area. There were collisions of course bit no real damage was done. We were at the school (now known as Bell View School for Girls) for about 10 days. We were then taken down to a shoe factory on the corner of the main road and New Street. We were to lodge in what was then the night watchman's accommodation. Another woman and her two young daughters joined us. She had told the authorities that she was related to us. In fact they lived further down the street and she thought it was better to live with somebody that you knew than with total strangers.

We were made very welcome by the factory staff and workers, in as much that they offered my mother and this other woman a part time job each. My mother accepted but the woman did not. This later led to confrontation because she was quite happy for my mother to feed her and her 2 daughters.

There was quite a large family living next door and they were very good to us. They showed us where the best fruit was for scrumping and where the best play areas were. We in turn showed them where the sheets of leather were kept.

At weekends when it was wet and we were not allowed into the street, we would enter the factory, collecting on our way a reasonable size sheet of leather, take it to the very top of the building where there was this track with rollers. We would place the leather onto the rollers and let it go and chase it all the way to the bottom. Somebody then had the bright idea of sitting on top of the leather. We fell off on many occasions before we perfected the run and apart from a few minor cuts and bruises no damage was done.

In the mornings we used to go to the little school at the end of the village. After school we would walk to the local recreation area for about an hour. By the time we got home Mum would have finished her shift and then we would muck in and get tea. It was about a month after the woman and Mum had the row that she finally accepted a job at the factory but asked not to be near where Mum was.

I cant recall having many air raids and people came round to make sure that there were no lights showing. There was one incident that I remember very well, and that was when everybody was asked to show as much light as possible. We later learned that there were some aircraft that had some problems, fully loaded with fuel and bombs and if they had to crash they did not want to land on populated areas.

One day our father arrived unexpectedly and said that it was now considered safe to return to London. We left unwillingly about a week later. We had a great time for about 9 months.

2 CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

I cant remember much about the start of the war except my father used to disappear on certain evenings. It was when we returned from our evacuation from South Wales that our street looked somewhat different. Passed the Infant School and not far from where we lived, there were some 4 houses that had fallen down. Then on our way to where my mother's mother lived there were some more and even across the road there were more houses that had fallen. I was told that air-planes had dropped bombs and this was why the houses were like they were. I was also told that we were not to go in them as they were dangerous and not to be played in.

At the bottom of our street there was an old wooden railway bridge and when the trains went across it, the noise was such that it used to keep us awake. Later we found out that the noise was to do with an anti-aircraft gun on the rails and it used to go to the areas that were being bombed.

After school there was not a lot to do, apart from collecting shrapnel (bits of metal from either bombs or anti-aircraft shells). Some cannon shells were also a collectable item. Later on there were the Butterfly Bombs (anti-personnel devices). These had a pair of little propeller blades and they used to float down so they did not explode on impact. (You touched them and they did!).

There was no television and no cinemas that we could go to at that time of the evening, so we had to invent things. There were about six or seven of us lads about the same age. One of them found an old motorcycle tyre and we organised races up and down the street. While one lad rolled his tyre up and down the others counted. We all took turns, the fastest being declared the winner.

Other tyres were found and in a short time we all had one. We used to use plaster from the ruins to mark out hopscotch grids, positions of goals and penalty areas for football. Coats or pullovers were used to mark the width of the goal down the middle of the road and very rarely did we have to remove them. A ball game we used to play was called Cannon. Two teams were formed and four pieces of firewood were placed against a wall in the form of a cricket wicket. One team would try to dislodge this wicket with a tennis ball (team A), if successful they would scatter away from the area and try to resurrect the wicket. However team B would try to stop this happening by trying to hit the members of team A with the tennis ball. Once hit by the ball you were out of the game until the game was restarted. Another game was rounders.

During the war years we used to have what was known as double summer time. At 10PM in the evening it was still very light and at times we were so engrossed in games that time was forgotten. These games would be interrupted by parents or others to remind us that it was late. It would be about this time of day we would watch the bombers flying quite high going to their targets. At times we would wonder if the children where the bombs were going to be dropped were being treated as we were.Were they getting tear gas dropped on them; and were they in the playground being shot at?

We were not allowed into the playground while there was an air raid on. When the all clear went, a teacher used to go out to see if it was safe. The following day about lunchtime the aircraft would return, some of them quite high but others very low. We used to stop what we were doing and marvel on how they were still flying in the condition that they were in. Some had engines stopped while others had tail parts missing and others had such large holes that you could see right through them. We also saw the vapour trails when the dogfights between Allied and the German fighter planes occurred.

On V.E. and V.J. days everybody local erected huge bonfires where the bombed houses had been to celebrate the end of the war.

3. FATHERS ROLE

I was born in London in 1935 within the sound of Bow Bells. In 1938 my parents, younger sister and myself moved to Grosvenor Terrace, which is in S.E London.

Before the war my father was a very keen football player and had taken some first aid courses, his job at that time was that of a bricklayer.

At the start of the war he volunteered as an Air Raid Warden. When he was called for the armed services, he was rejected on the grounds that with his knowledge he would be of better use in the Heavy Rescue, which was being set up.

He was stationed at a disused girls school about 3 miles from where we lived and so was able to come home when things were quiet. He accepted the fact that at times he would not be home as frequently as he liked or there may come a time when he might not at all. I was given the task, that in his absence, there were various jobs to be performed. Feeding the chickens, collecting the eggs, if there were any, and tickling the flowers on the plants with a fine paint brush. This was required because there were no or very few bees to do it for us. We were fortunate that both sets of grandparents lived in the same street, therefore if we ran short of anything they were on hand to help.

The function of the Heavy Rescue was to be on the scene as soon as possible after any bombs were dropped and to organise any rescue procedures that were required. This also involved the required ambulances and fire engines. He was soon promoted to be the team leader with the responsibility of having several teams under his leadership. His duties were to organise the scene and then move to another area and do the same until all areas were doing what they could in the circumstances.

There were times when we would not see him for days and then weeks;

Mother did not know whether he was alive or not. It was at this time that he started smoking. He developed into a very heavy smoker. As there was no chance of him getting regular supplies of cigarettes himself, and as they were in short supply, it was down to Mum and I to collect and supply them. The allowance was 100 per week. This satisfied dad for a short period of time. Eventually we were collecting 500 a week, they were the strongest that were on the market. He would use 1 match per day.

On the few occasions that we were out together he would make sure that together with the packet he was using he would have at least 2 more full packets. If he had to start a fresh packet while we were out, he would purchase another before we arrived home. While we were evacuated to Leicester he came to visit us. He had developed two growths in his throat. I was allowed time off from school to fetch ice so that he could put this around his throat to help him swallow. When these growths finally subsided he advised Mum not to purchase any more cigarettes. He put on a lot of weight and eventually died at the age of 92.

At the bottom of the playground of this school was a swimming pool. In the bottom of this empty pool there was placed a Master Searchlight. This had a very powerful beam and was used to locate the enemy aircraft. Once the planes were lit up the secondary or less powerful searchlight would take over allowing the Master Searchlight to look for other targets. The enemy realised the importance of this searchlight and tried to bomb it on many occasions but were unsuccessful because the crew used to move it to a different location every evening.

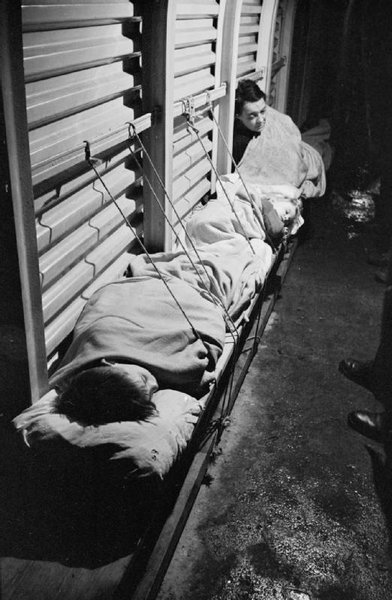

Because of the lack of ambulances, a lot of injured were laid along the pavement if it was safe to do so. If they had had to have severe bleeding stopped by very tight dressings, the time of the application of the dressing was marked in blood on their forehead. If a medic or firstaider noticed that the time of application had exceeded 15 minutes then the wound would be undone, allowed to bleed and then tightened up again and the new time marked on the forehead.

His main area of work was in the City of London or the Docklands where the bombing was more or less concentrated. A lot of buildings used to collapse and therefore block roads so that emergency crews could not get their vehicles to where they were required. In these incidents the crews had to carry their stretchers and hoses around or between the ruins before they could render any assistance.

One occasion (we learned later) there was a very large fire in the docklands, which he was trying to organise. He was called away to another emergency and when he returned within 15 minutes he found that more bombs had been dropped across the road where his fire was, causing a warehouse to collapse onto many fire engines and ambulances, killing the majority of their crews.

On one of his rare days off, he took me to a place some streets away from were we lived to show me something that had happened a week or so previously.

A parachute was seen coming down by the local A.R. Warden. With some colleagues they stood under the tree were the parachute was tangled within the branches. They called up but received no answer. Assuming the airman was either dead or injured a guard was placed until daylight. To their horror the airman was in fact a large metal cylinder, which turned out to be a landmine. The area was immediately evacuated until it could be defused.

The King and Queen were frequent visitors to bombed areas within days of the raids taking place, as was the Prime Minister. They also used to visit the school that was being used as my father's base.

My father was mentioned twice in despatches for courage and bravery.

Contributed originally by Donald Stepney (BBC WW2 People's War)

MY WAR 1939 – 1946

My name is Donald William Hutton Stepney, I was born on 23/08/24 to Betty and Walter Thomas Stepney of Staines in Middlesex. Father had served as a Sapper in The Royal Engineers during the 1914 –18 War and in 1939 we were living at 44, London Road Staines. The day war broke out – with apologies to that great comedian Mr Robb Wilton – my Mum said to me, “It’s up to you” I said “me” she said“yes” I said “why” she said “ Well, your Father did his bit in the trenches in the 1914 –18 War and now its your turn”

Well, on the 3rd September 1939 I had just turned 15 years of age and was attending Ashford (Middx)County Grammar School, was commencing my third year, was not very happy there and due to the outbreak of the war was only going to school one day a week initially. I found that due to the war pupils could leave school before the age of sixteen so I jumped at the chance and found myself a job in the Costs Office of the Staines Linoleum Co as junior clerk at a wage of seventeen shillings and sixpence a week.

In a few months when I became 16 I was allowed to become one of the Fire Watchers in the area where I lived, so my war effort began! Together with David Cooper, a friend of the same age and also two older men, we took turns on a rota system of Fire Watching in the area in which we lived. The headquarters were in a nearby disused shop, we went there from 9pm in the evening until 6am the following morning. Duties were to patrol the area and keep a lookout for fire incendiary bombs dropped by enemy aircraft and if necessary deal with them with a stirrup pump if possible. We lived in Staines about 16 miles from Hyde Park Corner. We were also a few miles from the railway marshalling yard at Feltham, a favourite target for enemy aircraft. A few bombs were ditched over Staines by aircraft returning from bombing London. Whilst on these firewatch duties one could see the huge glow in the air over London during the blitz. I did these duties for a year until I was 17 and joined the Works Home Guard unit. I did not have to deal with any incendiaries during this period but do recall one night when a stick of bombs weredropped about a quarter of a mile away from our home and that was just after the All Clear had sounded!!.

Home Guard duties were vastly different to fire watching. I was a private with the unit where I worked, this was a company that manufactured linoleum but now, in wartime was greatly turned over to various munitions manufacture. It’s site covered 50 acres and consisted of some 250 buildings of all shapes and sizes. It had it’s own power station and goods railway yard. It certainly warranted its own Home Guard unit. Specialist training was done with the local Middlesex Battalion Home Guard – Training with Machine Gun firing, Grenade throwing, Rifle and Bayonet use etc; all mostly done at weekends as were military manoeuvres with various other local units. Sadly I recall one Sunday morning, on Staines Moor when grenade throwing was being practised, a member of the town Home Guard was killed. On the lighter side I remember, whilst in the factory unit Home Guard that on the top of one seven storey building Air Observer duties were done on a rota basis. There was no shortage of volunteers for duty on a Thursday afternoon – Why? – well, binoculars were used of course to overlook the surrounds of the Staines area, and it was early closing day in the nearby High Street, so the shop girls and their boy friends spent the afternoon on Staines Moor – need I say more!!??!!.

Having registered for service in the armed forces when I became 17 and having indicated a preference for the Royal Navy, on the 18th May 1943 I was very pleased to be called upon to report to HMS Bristol, at Bristol.

This particular ‘ship’ was what is known, in naval jargon as a ‘stone frigate’ – It was a collection of Victorian built buildings on Ashley Down in Bristol and had originally been built as an orphanage by a George Muller and I believe these children’s homes, in the Bristol area, still exist today under that name. Gloucestershire County Cricket Ground is next to the site.

My medical had classed me as Grade 2 due to eyesight and up to this time in 1943 the RN did not take persons graded as such. However, in May 1943 things changed, and at HMS Bristol an eight week course had been set up to put recruits through their paces, assess the medical problems etc: and if all tests were passed, they were accepted into the RN. We were called Prob Ord. Seaman.

We did plenty of physical training (running round the County Cricket Ground) Rifle Drill, Route Marches etc: Some did not make the grade but I am pleased to say that I did and even took part in a parade in Portishead where a Naval Detachment was called for. I really enjoyed my time in HMS Bristol. If I remember correctly the Commanding Officer at that time was a Captain Walker RN who had previously had a distinguished naval career at sea.

In July 1943 I went to HMS Royal Arthur at Skegness ( This was another ‘stone frigate’ – prewar it was a Butlin’s Holiday Camp) here I changed to square rig and became a Prob Supply Assistant. On the 6th Aug’43 I went to President V in Highgate, London for a Supply Branch Training course. President V was Highgate College. Whilst here I was billeted at home, in Staines, and travelling Staines to Waterloo then Underground on the Northern Line. to Archway, morning and evening!

Previous to all this at some point during my induction period. I should add, I had been asked which naval depot I would prefer to be based at – Chatham, Portsmouth or Devonport?. Naturally, living at Staines I said either Portsmouth or Chatham would be suitable!. Naturally, again! I ended up a Devonport rating!!

On the 18th October 1943 having passed my Supply Branch exams I ended up at HMS Drake in Devonport as a Supply Assistant awaiting a draft posting. That was exactly 5 months after joining.

The 23rd Oct I joined HMS Brigadier who was attached to a buoy in Portland Harbour. I was an assistant to a Leading Supply Assistant and we were responsible for all Naval Stores (Engineering and Maintenance) Brigadier had been a cross channel ferry before the war – she was the SS Worthing and did the Newhaven – Dieppe run. When I joined she was a Landing Ship Infantry, she carried 6 Landing Craft Assault (LCA’s) I did not find out her full history until this year (2005) She was built in 1928 Tonnage of 2,343 gross. In 1939 she was a troop carrier, also a hospital Carrier during the Dunkirk evacuation. In 1940 a Fleet Air Arm target vessel. From 1941 she became an Infantry Landing Ship and carried out troop landing exercises in Scotland then eventually coming south to Portland where I joined her.

Crew wise she was a mixture of RN and T124X personnel. Officers were RNR and RNVR. Ratings were mostly RN and Combined Operations for the LCA’s. T124x rating s had been in the MN and still received that rate of pay – they were usually Stokers, Stewards, Cooks and Victualling Stores ratings.

All other ratings including the two Naval stores supply assistants were RN!

From when I joined Brigadier in Oct’43 until May ’44 we were on landing exercises along the mostly Devon coast, loading up with British, Canadian and American troops either at Portsmouth or Southampton and transporting them for practising assault landings in the LCA’s

On the 5th June 1944 HMS Brigadier departed the Solent as part of Assault Convoy J10 to land troops at the Juno beach-head on the morning of 6th June 1944. As far as I can remember we lost 2 of our LCAs that day when they went in to land. We came back to Portsmouth. late afternoon, it was very sunny, just off of Arromanches, we took onboard from a MTB, 2 badly wounded soldiers and one who had died and we brought them with us back home.

On this D Day as it was known, HMS Brigadier’s Landing Craft Assault Crews were part of 513 Flotilla and as far as I recall, their Petty Officer was named Croucher and came from Sunbury and the officer was Sub/Lt McMasters RNVR. The Captain was Cdr A Paramore RNR, Ist Lt was Lt D Winters RNR, Chief Engineer was Lt Cdr McLellan RNR and the Paymaster was SubLt D Love RNVR whocame from Hounslow

Some of the Rating friends I recall were LSA Frank Dart from Newton Abbot, Supply Asst William Dummett from Plymouth and Steward Bert Waller who had been on the ship when she was SS Worthing on the Newhaven/Dieppe run.

After the 6th of June Brigadier was part of a cross-channel shuttle service carrying reinforcements of all types, men an stores across to France. Once such journey included the Royal Navy’s own Dance Band,’ The Blue Mariners ‘ under the leadership of pianist Petty Officer George Crowe and featuring the noted alto saxophonist Freddy Gardner who was also of P O rank. The compere of this group that were going to entertain Service units in Europe was Sub Lt Eric Barker RNVR noted entertainer..

We had our moments of danger on these trips, such as, disposing of floating mines with rifle fire! Then there was the time I went aft on deck and saw the 28,000 tons of SS Monowi bearing down speedily upon us! There was a scraping noise on the starboard side but thankfully no serious damage!

The end for HMS Brigadier came on the 11/11/44 - It was a Saturday evening and we were leaving Southampton with 430 troops on board when we rammed the stern of HM Headquarters Ship Hilary at anchor at Spithead. The vessels were locked together and had to be cut apart, Brigadier’s bow was pushed back to the hawse pipes. She returned to Southampton the next day and paid off on the 18/12/44. I understand she was returned to Red Ensign service again and once more became SS Worthing on her Newhaven/Dieppe run! As a matter of interest she was sold to a Greek firm in 1954 and did cruisies in the Med under the name PHRYNI. Sadly she was broken up in Greece in 1954 after an illustrious career

After Christmas leave I was back to HMS Drake in Devonport awaiting draft. I should mention I was now a Leading Supply Assistant having applied to be upgraded whilst on Brigadier,. by virtue of the fact that I had passed my original exam with an 80% plus pass that allowed me to take that step.

On the 1st March 1945 I joined a Castle Class Corvette named HMS Headingham Castle at Blyth in Northumberland. She had recently been completed and it was my job to store her for commissioning. I was the sole supply branch rating aboard responsible to the First Lieutenant for all stores. I had an Able Seaman allocated as ‘Tanky’ (Assistant).

At this stage all the crew were gradually arriving but billeted ashore in Blyth as ship’s accommodation was not ready. One Able Seaman and myself were staying with a very hospitable family in Blyth they treated us as if we were their very own family members.I have always thought very highly of ‘Geordie’ folk since that period of my life.

Castle Class Corvettes were built for anti-submarine work and it was assumed that we would eventually be engaged on such activites. Commissioning took place and we did our ‘working up trials’ around Scotland at Tobermory,. Fairlie and ended up at Greenock. By this time VE Day had arrived whilst we were still at Blyth so when we had completed our trials it was assumed we would be making our way to the Far East. Then VJ Day arrived and that changed things completely. I cannot remember why but on VJ Day we were anchored off of Southend Pier and I recall travelling home to Staines on leave that very day!

Headingham Castle did not head for the Far East but as the war was over became based at Greenock and did three week periods in the North Atlantic as a Weather Ship

For some reason, known only to the Lords of The Admiralty! The crew of Headingham Castle, some 120 men, in Feb 1946 became the crew of HMS Oxford Castle and vice versa ! So eventually on Oxford Castle we ended up back at Portland Harbour. By this time Portland was an ASDIC training base. On the 18th May 1946 I was awarded my 1st 3yr Good Conduct Badge. As my Class A Naval Release was pending, in July’46 I was back at Devonport and drafted to DrakeII to await my release.

My waiting time was spent destoring a Cable ship that was moored at Turnchapel. For this period I was once again living ashore and actually stayed with my friend from HMS Brigadier days, Bill Dummett, he had already returned to civvy street and I boarded with him and his wife at their home in Hartley Vale, Plymouth,travelling into the City and over to Turnchapel each morning.

On the 24th September 1946 I was released from Naval Service from St Budeaux to proceed on 56 days resettlement leave.

I returned to my home with Mum and Dad in Staines, Middx and after my leave resumed my employment at the Staines Linoleum Co. All the members of the family had been very fortunate to survive World War II unscathed.