High Explosive Bomb at Victoria Dock Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Victoria Dock Road, Canning Town, London Borough of Newham, E14 0JW, London

Further details

56 20 SE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by ReggieYates (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Canning Town Evacuee — Part 1

My name is Reg Yates. I lived in London at Canning Town, London E.16 and Plaistow E.13 during WW2, going to Beckton Road Junior and Rosetta Road Schools except for my periods as an evacuee to Bath during September to Christmas 1939,then Cropredy May 1940 - July 1942.

I then worked at A. Bedwells, Barking Road delivering groceries for the rest of the war.

I'm still alive and kicking! Anyone remember me?

A Community Coming Together

War clouds came and we had to dig a big hole in each garden at least three and a half feet deep, at least six feet wide and roughly eight feet long depending on the size of the family using it, an awesome task. All the neighbours pooled resources and after about two months hard work most houses had a hole and had the Anderson Shelter erected to the supplied instructions. We had to make sure the rear exit worked properly. Two-tier bunk beds 2 x 6 feet one side and one other bunk bed and two chairs were there along with a bucket for the toilet and a bucket of water to drink. We never knew how long we would have to stay in there. During The Blitz we had to stay all night.

The shelters proved to be a godsend as they survived everything except a direct hit. They survived near misses and houses falling on top of them. People came out shaken but alive. They were worth their weight in gold.

There was another shelter built to fix over the kitchen table, steel top and legs for people who could get underneath in an emergency. Safe from falling masonry, it was called a Morrison Shelter after Lord Morrison a Labour Lord at the time.

I started smoking about this time. I could buy five woodbines and a box of matches for two pence, boys will be boys. I also remember going on an errand for my Dad, I had to take a letter to a house in Wanlip Road, Plaistow and she had tiles on the walk up from the gate to front door. She went ballistic because I dared to skate up to her front door. She made me take them off whilst she wrote a note to my Dad saying what a cheeky so and so I was for skating up to her door and that if I came again I would have to walk to teach me a lesson.

There were plenty of rumours about kids having to get evacuated very soon and on 1st September 1939 we were transported to Paddington Station and put on a train to the country.

We all had to say goodbye to our parents at school after they tied a label around our necks with name, date of birth, religion and which school we were from. So just after my eleventh birthday I said goodbye to Beckton Road School for the first time and landed up in the old city of Bath in Somerset.

Evacuated For The First Time

It was only two weeks after my eleventh birthday when we arrived at Bath Junction signal box, and someone said “just the thing for you kids from the smoke, a bloody great bath.” I didn’t realise what he meant until years later!

I was sent to a place called Walcott in Bath, and I was sent to a Mr & Mrs Pierce who to my eyes, were quite old looking. However, they were very nice people and looked after me very well.

They had a middle-aged navvy with whom I shared a bedroom, and our own beds I’m glad to say. I remember him getting dressed for work, hobnail boots, corduroy trousers and he tied about nine inches of car tyres around his kneecaps. He had a walrus moustache and looked a fearsome bloke to look at, but was a gentle chap really.

My two sisters were evacuated to a house just around the corner up a steep hill. Doris was eight years old and Joyce was thirteen and a half. They stayed with nice people who had two girls of their own of about eight to ten years of age. We all went to the local school along with about forty other kids from London.

We all had to sing a hymn ‘For those in peril on the sea.’ Just before Christmas we lost an aircraft carrier, HMS Glorious, with great loss of life and most of the sailors came from the West Country. The local rag had pages and pages of photos of those lost on the carrier.

Sometime in November 1939 I was playing a game called catch and kiss with some of the locals. This time they went along the road at the top of the hill. On one corner was a grocers shop, which had a wall with big white letters, “we sell Hovis bread”. What I didn’t know at that moment was that the police had very recently made the shopkeeper black it out as it could be seen from an aeroplane.

Running at full pelt, I ran straight into it thinking it was the turning. I was in hospital for three weeks. When I started school again, I could not see the teachers’ writing on the board.

At the end of December our Mum came to Bath to see us, and after saying goodbye to my sisters and all the other kids, she took me back to London so I could have treatment for my eyes. I had damaged my optic nerve and have worn glasses ever since.

Joyce came home in February 1940 when she was fourteen, but Doris stayed there until just before the end of the war in 1945.

Home Again

Christmas and New Year came and went, 1940 began and the war was getting worse. I think rationing was introduced about now and some foods were already becoming scarce. Cigarette cards disappeared from packets to save paper and you couldn’t buy pickles loose in a basket.

A couple of weeks went by and the time came to go back to school. Nothing much changed as most children who got evacuated the previous September were still away, but a few more seemed to come back every weekend.

The Beckton Road School was taken over by The National Fire Service, a first aid post and umpteen other things so they found the kids another school called Rosetta Road (off Freemasons Road) that was built of wood and all on one level after the First World War when all the servicemen came home.

Council workmen had dug some slit trenches just in case of an air raid but they looked useless to me, because if it rained it would be like running into a mud bath.

There was some talk about kids having to leave London again and come May it proved to be true and about seventy of us from this school were sent to Banbury in Oxfordshire.

Later in 1942 Mum and Dad moved to Wigston Road that was the next turning. Most people had moved because of the bombing.

Contributed originally by ReggieYates (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Canning Town Evacuee — Part 3

Starting Work

Having returned from being an evacuee, on my 14th birthday I started work for a firm called A. Bedwell & Sons who supplied grocery and provisions, delivering to grocery shops around London, Essex and some parts of Kent.

The firm no longer exists as the end of the war saw delivering to shops become outdated with big warehouses springing up who sold to shopkeepers willing to pay for goods as they wanted them in bulk.

I started as a van boy and when I was seventeen, I was officially allowed to drive a one ton van all by myself, and took another van boy on our delivery through Blackwall Tunnel, up the big hill to Blackheath and via Kidbrooke to Crystal Palace, then back via Lydenham and through Blackwall Tunnel again. Quite a nice day’s work, safe and sound. I really enjoyed myself and have never looked back.

We also had to pick up a load from various wharfs, another warehouse and some firms, at the same time looking out for any chance of getting things that were on ration. The war never ended until I was seventeen years old and rationing didn’t cease completely until about 1952, although as time passed things got easier and easier.

One of the vans I drove was an old model T type Ford with large back wheels and the body on top of the chassis, which made it heavy. It was hard to control in wet weather, the engine was so ‘clapped out’ it couldn’t climb a hill to save its life and it used half a gallon of oil every day which used to come out of the radiator cap with hot water, making an awful mess.

Going to one shop in Potters Bar we would fill the van right up to the maximum weight and at a big, long, steep hill we would try to get at least half way where there was a gate that allowed us to turn around and reverse the rest of the way up until just before the top where we turned around in a field and continued to the top facing the right way but smoking and steaming.

We kept complaining about the van and after about three months it would not start, so the garage mechanic said he would take it off the road and strip it down. The next day he called me in the garage to see the state of the engine. The van was eighteen years old so I expected the worst but was still amazed. The inside of the piston bore was red rust and oval instead of round and the valves were burnt so much that the round bit at the top of the valve was half the width they should be. He reckoned the engine had been running on fresh air for years.

He told the boss it would cost more to repair than to buy a new one, which was reluctantly agreed to and so he bought a smaller van which is similar to today’s transit.

The new van climbed the hill in Potters Bar first time, but on the way back I skidded it in the rain and finished side ways in a ditch which I managed to get towed out for a couple of quid. Luckily there was no damage apart from some paint scratches, which the mechanic sorted out for me for a drink. Nobody was any the wiser - I hope!

Another day I was driving a long wheelbase Bedford lorry in Leytonstone and the steering snapped, I hit the kerb and finished in someone’s front garden, lucky again! All this in my first year as a driver, mishap after mishap.

There was another time while I was driving to Romford in monsoon conditions at about ten in the morning, I got as far as The Dukes Head pub in Barking when I saw a trolley bus at a stop on the opposite side of the road and an army three ton lorry coming along behind it to overtake. The army lorry stopped beside the bus leaving me nowhere to go except between the army lorry and a lamp post which I did, but the top of the body and sides of my truck jammed between the lamp post and army lorry with the rest including me continuing down the road for twenty yards. To make matters worse all the goods were now exposed to the elements. It was like a scene from a Laurel and Hardy movie!

Fortunately for me a police car behind the army lorry stopped and the officer told the army driver to stay put, then guided me back under the van’s body. We borrowed some rope from a nearby garage and tied down the body to the floor. After ticking off the army driver for being so stupid he escorted me back to my firm near the Abbey Arms in Plaistow. Another one I got away with!

While I was a van boy and still only sixteen, (you couldn’t legally drive until seventeen) my driver decided to teach me how to drive the van. He put a blindfold on me and made me feel the gears, levers, clutch and gas. Then he revved the engine so I could hear the sound of the engine and feel the clutch ‘bite’, and drove so I would know by the sound of the engine when to change gear. Soon he taught me to drive the van for real on the quiet back roads and eventually let me on the open road.

Every Tuesday while he was courting, he would pick up his girlfriend from work and take her home where he went in for a bit of nookie. I had to wait in the van before we carried on with our deliveries. Her mother always used to make me apple pie and custard, which I ate in the van while waiting. Once he had taught me to drive, he let me take the van on my own (age sixteen) to continue deliveries while he had his nookie.

During Christmas 1945, my mate who was my driver got married to his girlfriend. She lived in Gidea Park, Romford and worked at Romford Steam Laundry (where Romford Police Station is now). The wedding was a big feast and drink up, which lasted right up to the New Year. His dad bought a forty gallon barrel of beer from the Slaters Arms and we pushed it home to his house, where we took his back fence down so we could get it in the garden and lift it on to a stand he had made so we could get the beer easier.

His dad said “nobody goes home until all the grub and beer has all gone”, so we stuffed ourselves silly with all the drivers eating 30lb of cheese, 4 x 7lb of spam, 10lb of butter, a big bag of spuds, many loaves of bread, 10lb of bacon, three dozen eggs, 4lb of tea, a case of evaporated milk and a big bar of Ships chocolate used for making drinks.

I got home on New Year’s Day at teatime stinking like a polecat with a week’s growth of hair on my face. I really enjoyed myself.

Starting back at work I found two new Morris Commercial three-ton lorries and I got one after we all tossed up coins to see who would get them. Lucky me, it was a lovely lorry to drive, pretty fast as well.

Coming back from Chatham the police would chase us every week for speeding, but could not catch us because we were having a cuppa in a wayside café when they caught up with us. Mind you the police in those days had 200cc motorbikes. It was not until later that they had much faster bikes like 500cc Nortons and Triumphs.

It was not long after this incident that I had to go to a South London wharf in Tooley Street to pick up five tons of sultanas. Coming up to Tower Bridge, the bridge was up, so I crept up on the outside of the queue of traffic. In those days there were still a lot of horse and carts around so it was a crawl over the bridge.

Just as I got over the bridge on the east side I saw an old motor coach come out of Royal Mint Street onto Tower Bridge. There was an obelisk there dividing the road for southbound traffic but you could go either side. I stopped dead so the coach could get by and a horse and cart came up on my near side. The coach kept coming and I could see that it was going to hit us if it didn’t pull over a bit, so I told my van boy to quickly get under the dashboard and curl up.

Unfortunately the coach did hit us, right in the radiator and the bonnet flew off into the River Thames. Our engine came back into the cab, the gearbox came up through the floor and five tons of sultanas went all over the cab. Both doors caved in trapping me in the cab right against the steering wheel and the offside front lamp of the coach came through the nearside windscreen, frightening my van boy because he could not move.

Somebody called the police, fire brigade and ambulance. Fortunately they managed to get my van boy out in minutes, but I was stuck for about forty minutes until they cut the steering wheel in half and forced the door out.

Imagine my surprise when I was pulled out, I never even had a scratch. My saviour was a leather belt I wore to keep my trousers up and an old army belt I used to wear around my boiler suit. The steering wheel went flat where it hit my belt and saved me from any injury.

When I got to hospital they could not believe that I didn’t even have a bruise. I was so lucky.

The coach driver had more room than me to get by and needless to say, he was charged for driving without due care and attention.

These are just a few of my memories of WW2. I hope you enjoy them. I am certainly enjoying reading all the stories from other people.

I now live in Devon.

Contributed originally by angaval (BBC WW2 People's War)

It is September 1940 and I am returning from Chrisp Street Market with my mother. I'm nearly seven and I've come back to London after being evacuated to Glastonbury during the 'phoney war'. It's a lovely warm evening and my mum is anxious to get back home with her shopping.

As we begin to turn into Brunswick Road, we hear the sound of gunfire - not unusual, as we live near the East India Docks and there is frequent gunnery practice. But then we hear the planes and the air raid sirens. ARP wardens are running about blowing whistles, shouting, 'Take cover, take cover!' We start running the last few yards home.

My dad is panicking and my nana (who speaks little English) is hysterical. We then all bolt into the Anderson shelter in the back yard, just as the first bombs start exploding. My Dad hates the Anderson as it's always full of spiders and he's scared of them. The noise is horrendous. Every time a bomb falls near, everything shakes. Above us there is the 'voom, voom, voom' sound of the planes. The ack-ack guns make a hollow booming noise and the Bofors make a rapid staccato rattle. It seems to go on for hours and then, suddenly, there is a pause, then the 'all clear'.

Stunned by the noise, we emerge. The house is still standing and doesn't seem damaged. We go out through the front door to see a scene which even now I recall as vividly as when it happened. The entire street is choked with emergency vehicles - ambulances, fire engines - all clanging their bells. The gutters and pavements are full of writhing hoses like giant snakes, and above... the sky. The sky - to the south, still a deep, beautiful blue, but to the north a vision of hell. It is red, it is orange, it is luminous yellow. It writhes in billows, it is threaded through with wisps and clouds of grey smoke and white steam. All around there are shouts and occasional screams, whistles blow and bells clang.

The neighbours stand around in small groups. They talk quietly and seem as dazed as us. Apparently most of the flames are from the Lloyd Loom factory down the road, which has taken a direct hit. The gutters run with water, soot and oily rainbows and the reflections of the fiery sky. Our respite does not last long. About 20 minutes later, another alert, we are back in the Anderson, and it all begins again.

The noise makes my knees hurt. When I tell my mother, she laughs and says it's growing pains. Maybe, maybe, but for the rest of the war; whenever there was a raid my knees always ached!

Contributed originally by Leeds Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

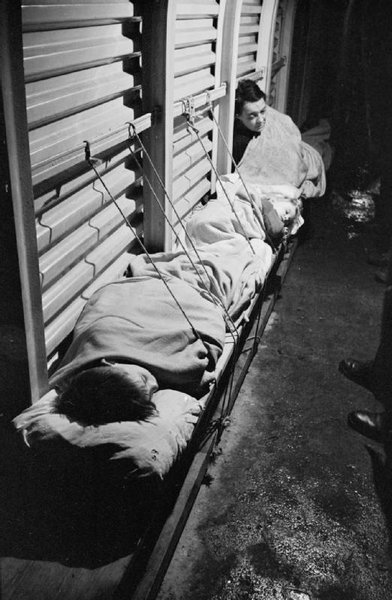

They were happy times but at the age of nine and a half, 1938, things changed. The powers that be decided I was small for my age and underweight so I was sent to an open-air school at Fyfield in Essex, where I spent the next 18months, being just a number amongst about a hundred and fifty other girls. We all slept in long dormitories with one side open to the weather except when we had a thunderstorm.

The classrooms were the same, each one set in a large open space. Meals were served in a large wooden hall on long wooden tables and we sat on long wooden forms. Brown bread and warm milk, porridge you could cut with a knife and if it was not eaten you went without. All meals were served in enamel mugs and dishes and to get one that was not chipped was a bonus.

Sunday walks to church are vivid in my mind. In lines of two, girls at the front and boys at the back we went through country lanes and little villages. Things of interest were pointed out to us and this is where I began to appreciate the beauty of the countryside.

Visitors such as parents were allowed to come to the school on one afternoon every three months and this was a great day. Every child had to learn to sing ‘Jerusalem,’ ‘Nymphs and Shepherds’ and ‘Oh for the Wings of a Dove.’ These songs were sung at assembly when all the visitors had arrived and sometimes when I am resting I can hear the singing still.

One morning I was amazed to see a large balloon in the sky [barrage balloon — large silver balloon with ropes dangling from it to catch planes flying in low] we all thought it was an elephant! We were all frightened and wondered what it was going to do. No one knew what it was or where it had come from. It was some weeks before we were told and the mystery was solved. I can’t remember the exact day we were told to line up in the playground for a special announcement.

We were then told to empty our lockers, collect all our belongings and report back to the nurse who would give us our own clothes which we were to change into at once as we were being taken home. I was too excited to wonder why this was suddenly happening but late that afternoon we boarded buses and as we were driven out of the school gates buses were coming into school from the opposite direction bringing sick and crippled children out of London. These were the children from the hospitals and orphanages, any sick children that needed looking after. We’d never seen children like that because they were so sickly. We didn’t know why they were being brought in.

It was only when we got home we were told the country may be involved in a war and these children had to be brought to a place of safety in case London was bombed. At that point they were thinking about evacuating children.

Things were very different at home but I soon settled; only eight of us, out of fourteen children, were at home now with mum and dad, five boys and three girls. The others were all married. We were all happy for a while. September 1939 war was declared between England and Germany. Things would never be the same. Three brothers left home the same day, two went in the air force to France and ended up in Dunkirk and one went to Gibraltar and one into the army ended up in Burma. They were all in the Territorial Army before this so had to report immediately. I remember them putting their three kit bags on the table and packing their kit. I’ll always remember the three of them walking away together.

All civilians were given an identity number and identity card, a gas mask in a small square cardboard box with a cord attached to it to enable us to carry it everywhere we went. Tiny babies were given a ‘Mickey Mouse’ gas mask, it was coloured and they were put right inside it. Some of the small children had ‘Mickey Mouse’ gas masks so they weren’t scared to put them on.

Schools closed and cinemas and most places of entertainment shut their doors. Food, clothes and coal were rationed. I remember taking an old pram and standing in a queue for hours to get one sack of coal.

By this time another brother had been called up to go into the air force. He was sent to Egypt. The brothers who were sent to Egypt and Burma went on sister ships and met in Durban, South Africa, before one headed to Asia and the other to the Middle East.

When I met my husband three years after the war I brought him home and he recognised my brother. They had served together in Burma.

My brother ‘Bert was at Dunkirk and was saved by a colleague in the Air Force. He pulled him out of the water, into a boat, when he was being machine-gunned. The air man came to our house for us to say ‘thank you,’ met one of my sisters, married her and became one of the family!

Most of the children in London had been evacuated to the country for safety. I stayed at home; my parents wanted me with them. Before the boys went away they had put an Anderson shelter in the garden for our safety. It was a double sized shelter and took up most of the garden. There were bunks down both sides. We spent a few months sleeping in there every night, we never bothered going to bed upstairs, you knew you’d be woken up in the night.

Our house was in the East End of London and when the air raids started this part of the South of England was given the name of ‘Bomb Alley.’ It was very frightening. By this time we were getting used to the routine of going to bed in the shelter night after night.

Early one morning the police called us from the shelter and said, “Grab what you can from the house as time is short and go to the end of the road.” Everyone took a bundle of things wrapped in a sheet or tablecloth. Then the police told us to find somewhere to stay because there was an unexploded bomb near the house.

The air was full of smoke; fires were burning everywhere we looked. There were no buses so we had to walk to the safest station where we managed to get a train, after the ‘all clear’ sounded, to Romford because my sister had a house there.

Living in Romford was nice. We could sleep in a bed again and the bombing was not so bad. My youngest brother was called up for the navy but he was to be a Bevan boy, which meant he was sent up north to Mansfield, to work down the mines.

I suddenly found myself on my own with elderly parents and I had a much bigger part to play digging the allotment, planting veg, to help rations go round, making bread and standing in queues for hours. I also became a member of the training corps and was taught to fire a rifle.

At fourteen I started work. The war was still on and as soon as I was fifteen I took a job in a factory making wing ribs for Spitfires. Suddenly I had grown up and felt I was at last doing something worthwhile to help the rest of my family.

There were funny times in the factory. When the sirens sounded we had to switch off all machines and make for the trenches in the field across the main road. We would all crouch down and watch the Battle of Britain being fought above our heads. We didn’t have time to be afraid someone would see the funny side of the situation and we’d all begin to laugh, every time!

War is a terrible thing, it is surprising how people would come together in times of need. Food was very short, rationing was hard but no one starved. If a child had a birthday all the neighbours would give what they could and a birthday cake would appear, and we would all get together for a party.

Christmas presents were lovingly made by Granddads who would make trains, boats, cars, out of old bits of wood. Anything that could be used was used, but no one ever made a toy gun. Grandmas knitted dolls clothes from unwoven woolly jumpers. My sisters and I made soft elephants and rabbits from old clothes and stuffed them with scraps of rag left over from the cloth rugs we made. Every house had a homemade rug. Strips of old clothes were cut and threaded through a piece of sacking ad knotted at the back and then a huge piece of sacking was sewn on the back. Patterns could be made with all the different colours of cloth and some were very grand after they were trimmed. Making rugs was a popular pastime, which kept us occupied in the shelters, young and old could all help.

Going out was not a thing we did unless it was necessary, even then we would be sure we could get to a shelter if the sirens sounded. I don’t think anyone was comfortable walking in the blackout. One Friday evening my brother was riding his bike home from work, in the black out. Unfortunately a family were moving house and had left a flat barrow piled with furniture in the road, in the complete darkness. My brother ran into the barrow with such force he bit his tongue in half. When he staggered in the house, blood all over him, everyone forgot me in the bath and dashed off to the hospital where a very clever doctor stitched his tongue together again. He still has a lisp to this day.

Travelling was difficult even with an identity card. I went to see my sister on the Isle of Wight. I had to go to the police, who gave me a permit to travel. That was because I would be going through Portsmouth or Southampton and they were royal navy dockyards.

My eldest brother was the civil engineer in charge of the American army camp at Tewkesbury in Gloucestershire. He came to London on one occasion and I thought it would be nice for me to back with him to his family for a break. He had a daughter my age. Once again I had to get permission from the local police and give them all the details of my intended movements.

What a holiday that was! They were still having barn dances in the local church hall. It seemed to me the war had not changed much. Italian prisoners of war worked in the fields in the camp. My brother’s house was on the road, inside the camp. Shirley was my niece and we were good pals. She was a brilliant musician and could play the piano and accordion.

Sometimes we would sit in the front garden of the house and she would play the accordion. In the field opposite Italian prisoners would be working. As soon as they heard the music they would sing their hearts out. They had a prisoner working in the house; he did the housework and was well behaved. Sometimes he would bring a list of music for Shirley to play. He said it reminded them all of home.

In 1941 the war was still raging. Most of Europe was occupied by German troops. France had fallen and there was only the channel between them and us.

It was not until I went to Yugoslavia, years later, that I realised how close to England France was.

So much had happened. I now had a brother serving in Burma, one in Egypt, another in the king’s flight with the RAF and one had returned safe from Dunkirk. Food, clothing, sweets and coal were rationed. Underwear was a big problem which some of us solved because we were able to get damaged parachutes. These chutes were made of fine white nylon and providing someone in the family had a sewing machine and a little bit of dressmaking skill the finished garments were beautiful. Also if we could acquire an army blanket or even better an air force blanket we could make a warm topcoat. I myself altered RAF trousers into ladies slacks. They were very rough on our skin but very warm. At one time after we had used all our clothing coupons up and we needed new shoes we tried clogs. That resulted in too many sprained ankles so we soon went back to the well worn out shoes.

The blackout was very necessary. We had to be very careful if we used a torch or lit a cigarette. The smallest light could be seen from the air and Air Raid wardens were always on patrol to make sure everyone observed the rules. If a light was seen you could be accused of signalling the enemy.

If we ventured out in the blackout we would always go in groups of three or more. Although we did not smoke, one of us would hold a lighted cigarette in our hand. This we hoped would make them think we had a man with us and made us feel much safer.

My sister lived in Romford and we were able to stay in her house until my parents could rent a house. This house was in the same road as my sister’s. There was a brick built shelter at the bottom of the garden and my father soon made bunk beds for us and we had a small camping stove on which we could make tea.

Some people had indoor shelters these were called Morrison shelters. They looked like reinforced cages. They were about six foot square and we had to crawl into them and lie down. There wasn’t enough room to sit up but with a blanket and a pillow you could be quite comfortable. Most families had them in the dining room and used them as tables.

Although we were away from London the air raids were quite bad and quite a lot of bombs were dropped on this part of Essex. Doodlebugs and V2 rockets were still coming over. People seemed to take everything in their stride and just carry on with their lives. We shared things we had and made the best of things. We always managed to see the funny side of something so there was plenty of laughter.

In 1941 Germany attacked Russia and it was bad news every time we listened to the radio. Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbour and the United States of America came into the war on our side. What a surprise they were. There were sweets, chocolate, chewing gum, cigarettes and nylons. They had everything and soon became very popular with the teenage girls.

Dances were held at their barracks ever week. It was fun to see the girls changing from work clothes into dresses suitable to go dancing in. Coffee or tea was used to dye their legs and they would draw a line at the back of the legs to look like a seam. If it rained it was a disaster, the dye would run and their legs became striped.

The Glen Miller Band came over from the States and their music was extremely popular. Music While You Work was broadcast every morning to the factory. We all found it very hard to stand still. We would be Jitterbugging with hammers in our hands. Everyone cheered up and sang. The more patriotic the music the louder we would sing.

When things were going bad for the Allies some songs were banned. It was upsetting for some families who had relatives serving abroad. ‘The Little Boy That Santa Claus Forgot’ and ‘Russian Rose’ were two we did not hear again until the war ended.

Contributed originally by sunnydigger (BBC WW2 People's War)

We lived in Old Canning Town in the East End of London.In 1940 after a devastating weekend during which several families lost their homes because of German bombing they were told by the local council to make their way to a school in South Hallsville Road where they would be temporaily housed whilst buses would be orgnised to take them out of London and into the relative safety of the suburbs. Some of these unfortunate people spent the three nights from Saturday 7th to Monday 9th waiting for the buses, but the buses did not materialise. No one really knew what had gone wrong but it appeared that the bus convoy had gone to Camden Town in mistake for Canning Town. After which they were then hampered in their journey to Canning Town by blocked roads and diversions

Long before the buses reached Canning Town the Luftwaffe had returned and at 3.50 a.m. on the morning of Tuesday 10th the school received a direct hit, probably from a land-mine dropped by parchute. Some four hundred people perished in the rubble amongst them were many of our friends. No other expolsive device which fell on Britaiin caused so many fatalities. Providentially, my family had not gone to the school as our house was undamaged. However, in time we did have to move as we were bombed out in 1941, we suffered no physical injuries as we were in the corrugated Anderson Shelter when the bombs fell. This shelter was cold, damp and very unpopula, but looking back they must have saved many lives. We were evacuated from the East End to Hammersmith West London. and moved to a block of flats called Peabody Buildings Fulham Palace Road, we occupied a ground floor flat with two floors above us.

During the time my family was in the flat I had joined the Royal Marines 1943. Everything was going reasonably well for us considering it was wartime. In the summer of 1944 i was stationed at Westcliff just fifty miles down the line from London, so each evening i went home on unofficial leave, stayed the night and returned by the first train in the morning. On the night of August 22-44 my Mom and Dad were sheltering in the Underground Railway station which they did every night to get away from the bombing while I stayed at the flat and was in bed when Peabody Building was hit by a bomb and collapsed into rubble underneath which I was trapped for three hours. Once again we had lost all our possessions. All I was left with were my underpants and vest.

Someone gave me some clothing and a pair of shoes and I went to the Royal Marines Headquarters at Queen Ann’s Mansions. The duty after telling him what happend he gave me a travel warrant back to Westcliff and a letter to my Company Commander autorising the replacement issue of the lost items of my kit and granting of Seven days emergency leave, I was never asked how I came to be at home in London in the first place.

The family found a new at Ellingham Road Shepards Bush W.12 London, and we started all over again. I am pleased to say we remained there without further disturbance. After leaving the Marines in 1947, and working in and around London my wife and myself moved to Canada. Both my Mom and Dad passed away some years later.

We lived in Old Canning Town in the East End of London.In 1940 after a devastating weekend during which several families lost their homes because of German bombing they were told by the local council to make their way to a school in South Hallsville Road where they would be temporaily housed whilst buses would be orgnised to take them out of London and into the relative safety of the suburbs. Some of these unfortunate people spent the three nights from Saturday 7th to Monday 9th waiting for the buses, but the buses did not materialise. No one really knew what had gone wrong but it appeared that the bus convoy had gone to Camden Town in mistake for Canning Town. After which they were then hampered in their journey to Canning Town by blocked roads and diversions

Long before the buses reached Canning Town the Luftwaffe had returned and at 3.50 a.m. on the morning of Tuesday 10th the school received a direct hit, probably from a land-mine dropped by parchute. Some four hundred people perished in the rubble amongst them were many of our friends. No other expolsive device which fell on Britaiin caused so many fatalities. Providentially, my family had not gone to the school as our house was undamaged. However, in time we did have to move as we were bombed out in 1941, we suffered no physical injuries as we were in the corrugated Anderson Shelter when the bombs fell. This shelter was cold, damp and very unpopula, but looking back they must have saved many lives. We were evacuated from the East End to Hammersmith West London. and moved to a block of flats called Peabody Buildings Fulham Palace Road, we occupied a ground floor flat with two floors above us.

During the time my family was in the flat I had joined the Royal Marines 1943. Everything was going reasonably well for us considering it was wartime. In the summer of 1944 i was stationed at Westcliff just fifty miles down the line from London, so each evening i went home on unofficial leave, stayed the night and returned by the first train in the morning. On the night of August 22-44 my Mom and Dad were sheltering in the Underground Railway station which they did every night to get away from the bombing while I stayed at the flat and was in bed when Peabody Building was hit by a bomb and collapsed into rubble underneath which I was trapped for three hours. Once again we had lost all our possessions. All I was left with were my underpants and vest.

Someone gave me some clothing and a pair of shoes and I went to the Royal Marines Headquarters at Queen Ann’s Mansions. The duty after telling him what happend he gave me a travel warrant back to Westcliff and a letter to my Company Commander autorising the replacement issue of the lost items of my kit and granting of Seven days emergency leave, I was never asked how I came to be at home in London in the first place.

The family found a new at Ellingham Road Shepards Bush W.12 London, and we started all over again. I am pleased to say we remained there without further disturbance. After leaving the Marines in 1947, and working in and around London my wife and myself moved to Canada. Both my Mom and Dad passed away some years later.

We lived in Old Canning Town in the East End of London.In 1940 after a devastating weekend during which several families lost their homes because of German bombing they were told by the local council to make their way to a school in South Hallsville Road where they would be temporaily housed whilst buses would be orgnised to take them out of London and into the relative safety of the suburbs. Some of these unfortunate people spent the three nights from Saturday 7th to Monday 9th waiting for the buses, but the buses did not materialise. No one really knew what had gone wrong but it appeared that the bus convoy had gone to Camden Town in mistake for Canning Town. After which they were then hampered in their journey to Canning Town by blocked roads and diversions

Long before the buses reached Canning Town the Luftwaffe had returned and at 3.50 a.m. on the morning of Tuesday 10th the school received a direct hit, probably from a land-mine dropped by parchute. Some four hundred people perished in the rubble amongst them were many of our friends. No other expolsive device which fell on Britaiin caused so many fatalities. Providentially, my family had not gone to the school as our house was undamaged. However, in time we did have to move as we were bombed out in 1941, we suffered no physical injuries as we were in the corrugated Anderson Shelter when the bombs fell. This shelter was cold, damp and very unpopula, but looking back they must have saved many lives. We were evacuated from the East End to Hammersmith West London. and moved to a block of flats called Peabody Buildings Fulham Palace Road, we occupied a ground floor flat with two floors above us.

During the time my family was in the flat I had joined the Royal Marines 1943. Everything was going reasonably well for us considering it was wartime. In the summer of 1944 i was stationed at Westcliff just fifty miles down the line from London, so each evening i went home on unofficial leave, stayed the night and returned by the first train in the morning. On the night of August 22-44 my Mom and Dad were sheltering in the Underground Railway station which they did every night to get away from the bombing while I stayed at the flat and was in bed when Peabody Building was hit by a bomb and collapsed into rubble underneath which I was trapped for three hours. Once again we had lost all our possessions. All I was left with were my underpants and vest.

Someone gave me some clothing and a pair of shoes and I went to the Royal Marines Headquarters at Queen Ann’s Mansions. The duty after telling him what happend he gave me a travel warrant back to Westcliff and a letter to my Company Commander autorising the replacement issue of the lost items of my kit and granting of Seven days emergency leave, I was never asked how I came to be at home in London in the first place.

The family found a new at Ellingham Road Shepards Bush W.12 London, and we started all over again. I am pleased to say we remained there without further disturbance. After leaving the Marines in 1947, and working in and around London my wife and myself moved to Canada. Both my Mom and Dad passed away some years later.