High Explosive Bomb at Fitzroy Square

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Fitzroy Square, London Borough of Camden, W1T 5HP, London

Further details

56 20 SW - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by Franc Colombo (BBC WW2 People's War)

ENGLAND PART FOUR

When we got ashore we were met by nurses and volunteer women who made a fuss of us then took us to a big marquee given tea and sandwiches then to a room where our pay book was checked then given travel warrants and told to report to our depot. I arrived at Hounslow in the evening, after settling down I phoned my father to say that I was safe he was pleased to hear from me because by that time he heard the news of the evacuation, in due course the remainder of the battalion arrived, I learnt that quite a few were killed, wounded or missing, fortunately my friends where O.K, finally I met up with my officer and he wanted to know what happened to me. Soon as we were refitted we were posted on the Isle of Wight, we were expecting the Germans to invade, we had few weapons one rifle between two men some just had pitch folks or pick handles, bit by bit we received new weapons, by this time the battle of Britain started, we heard that London and other cities were being bombed, we had our share one bomb dropping on the cook house causing many casualties, luckily it was not meal time.

Our next move was back on the mainland doing training and route marches of twenty miles. I was due to go on leave but before going I had to see the company commander who told me that being Italy declared war on England and being that I came from an Italian family there was the possibility that if I was captured I could be shot therefore I could transfer to a non combat unit I told him that England was my country. When I got home I told my father about it and he told me that I should fight for my country, he also told me that Bastiano and Armando had been interned and he was trying to get them released.

Armando was interned because his mother Fernanda never liked England and sent him to an Italian school and was registered as a fascist. I remember one time when I visited Jinnie and fernanda was there and she said that she could not understand how I could go and fight against the Italians, I told her that they declared war on my country and if I came up against them so be it.

When I went round London I saw the destruction the bombers made, where houses and shops stood there was just a gap and rubble, fortunately round Edgware road they had no damage. In the evening I would visit my friends and we would go to the west end, for a drink it was strange to see so many uniforms and nationalities, many times we had to take shelter because of the raids. While I was on leave I contacted the red cross to see if I could get a message to Tinuccia, I was able to send a card to say that I was well, later we were able to correspond more frequent. Shortly after returning from leave we moved to Newbury, we were billeted on the racecourse just on the edge of town which suited everybody, Newbury was a friendly town and had quite a few places for entertainment.

While we were there Capt. Hill told me that he was being posted to another battalion and would I go with him, I told him that I had applied for a transfer to the airborne division and therefore I would not join him. On the 13th Dec. 1941 we went to Invarery Scotland for combined operation training, we had to live on board a ship in the middle of the lake and sleep in hammocks, we had some fun trying to swing into them but we soon got the hang of it, then we had to learn how to scramble up and down the side of the ship by a rope ladder into an assault craft, in the beginning we found it hard going but after a few times we were going up and down like monkeys. The exercise was landing on the beaches.

We had Christmas dinner with a pint of beer on the ship the rest of the day was our own. The following day the C. O. thought it would be a good idea that after all that food and drink we consumed the previous day we should sweat it out, so we were put ashore by platoons and do a thirty miles march finishing going up a steep hill which terminated on top of a cliff and scrambling down a rope and back to the ship . When our training was over we returned to Newbury, by this time I was receiving letters from Tinuccia, few and far between but at least I knew she was alright and that the feeling for each other was the same, in her letter she told me that one of her cousins had gone to Tunis and that she gave her some letters for me and that if ever I was there I could pick them up.

Our next move was to Camberly, in between manoeuvres we had a visit by King George the VI. I remember that it was a very cold day and light snow on the ground, it was decided that he would come and see us doing training in a field, our company was chosen to do physical training, we arrived at the field in our greatcoats an hour before he was due. When he showed up we removed our greatcoats and just in shorts and vest started to do P.T. when he saw us apparently he was annoyed and told the officers that we should return to our billets given a hot drink and a rum ration.

In April 1942 we were on the move again back to Scotland but this time we were going to walk, we were supposed to be chasing a retreating enemy, we did 130 miles in seven days. We arrived at Stops camp 5 miles outside the border town of Hawick. Contrary to the reputation that the Scots were mean we found them to be the most generous and kind hearted people we ever met, the hospitality of the habitants of Hawick was overwhelming, every man had a household to which he could go when he was in town and be sure of a meal, my friend Frank Vincent and I were taken in by mr. and mrs Nayler and treated as their sons.

Soon after settling down the anti tank platoon was formed I asked to be transfer to it because I was in it when we were in Shornecliff, soon after I was promoted to lance corporal. The training was hard but we were fit, one part was that with my section of 7 men we were taken in the glens miles from anywhere and had to live on the land for 48 hours making our way back to camp using a compass, in the morning we stopped at a farm to ask for some water to make tea, the farmers wife asked us what we had been doing, we told her that we had been out all night she invited us in and gave us a full breakfast and sandwiches to take with us, we finally arrived back in camp, we were not the first but we were not the last.

By this time I was made full corporal in charge of a gun, then came news that we were going on embarkation leave, the train to London did not leave till midnight Mrs Naylor insisted that Frank and I would have dinner with them and made us sandwiches for the journey, the train was packed and we had to sit in the corridor all night. Finely I arrived home and I was told that with fathers intervention Basil and Armando were released from interment. Soon after Armando was called to join the army. I visited all the family because I knew that it would be a long time before I would see them again, I shut it out of my mind that I might never return.

Then I visited my friends and as luck would have it they were also on leave therefore it was an occasion for a celebration and going to the West End and having a good time, one night we went to see Gone with the Wind, it was the rage then. All to soon leave came to an end I told father that it would be sometime before I would see him again, so I returned to Stobs Camp. We learned that we were moving out in a few days, Frank and I went into Hawick to say our farewells to the Naylers, they were sorry to see us go and wished us luck and a safe return.

The following night 9th of March we marched to the station and boarded the train for Liverpool the port of embarkation.

We went on board and taken to our allotted space, it was cramped but we soon sorted ourselves out and we had our old friend the hammock, then with Polly and some other chaps went on deck to have a look round saw some other ships which would make up the convoy. Our ship was the S.S. Cuba a French ship. The following we were shown our boat stations and boat drill.

Two days later we set sail and taking our position in the convoy. In the bay of Biscay I found it difficult moving around and I was seasick but it soon passed and I got my sea legs, it felt strange because I could move around without feeling the lurching of the ship. The days passed with P.T. lectures boat drills and other activities, several times we had air raids, guns going off every where then we went though the Strait of Gibralter and into the Mediteranian, then one day we were attacked by submarines, they managed to sink two ships, one was a troop ship the Winsor Castle, we were at our boat station and saw her sinking, the destroyers chasing every where dropping depth charges then picking up survivors. The following day we sighted Algiers, it was impressive with its white tall buildings, it looked nice till we landed.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

By the middle of September, the Doodlebug raids had quietened down a bit. All the launching sites in France were now captured by our troops.

The Germans moved operations farther north to the lowlands, and most Doodlebugs were launched from parent aircraft over the North Sea, so Essex became the direction from which they approached London. Not so many got through however, as the RAF were waiting for them. Those that did make it caused many casualties though, as most people were by now just getting on with their lives and not taking shelter until the last minute.

One Friday morning at the beginning of November 1944, my brother Percy and I were in the kitchen behind the shop having our "elevensies," when there was a huge bang followed by another one like an echo, then a whooshing noise. The ceiling seemed to come down and hit us then go up again, dust flew everywhere.

Shaken out of our wits, we rushed outside and saw that something had dropped at the top of the road. We left the Shop and ran up there to find a scene of devastation. Our first V2 had arrived.

The huge steel framework section of the Railway Arch that formerely spanned the main road was now standing on the ground, with a heap of mangled wreckage behind it. An Electric Train with the letter P on the front was leaning against the brick parapet on the approach to the bridge.

On the road, in the middle of the T junction, the wreckage of a car was burning furiously. I still remember the badge on the radiator, which was about all that was left on the chassis. It read: "Morris Major". Of the driver and any passengers there was no sign. Black smoke from it's burning tyres joined the cloud of smoke and dust hovering over the scene, but we were the only living souls about for the moment, it seemed.

The "John Bull" Pub and all the shops and houses within about 200 yards of the Arch were flattened. The Licensee's Wife, a very nice old Jewish lady, and the Cleaner, who were working in the Bar at the time, were among those killed.

Dad got home from the Market soon after, and the two bereaved husbands, who were friends of his, stayed in the shop with us all day. They were both in a state of shock, grieving their terrible losses.

Many of the terraced houses on both sides of our road near the junction were demolished, including the house where the Girl who later became my Wife lived, but luckily this one was empty at the time.

Many people were not so fortunate though.

There were so many dead bodies that they turned the Manor Methodist Chapel, round the corner in Ambrose Street, into a temporary Mortuary so that relatives could identify their loved ones. We lost quite a few regular customers that day.

By some sort of coincidence, another V2 landed in exactly the same place two Sundays later, just before midday.

Most of the debris from the first V2 had been cleared, and a temporary Bridge of massive timbers erected. This was demolished of course, but there wasn't much more the Rocket could do, as the area was already flattened.

The only casualty I know of was an elderly Gent, a Bookmaker's Runner known as "Nibbo". He'd been standing outside a Pub called the "Ancient Foresters", waiting for it to open.

This Pub was quite close to the John Bull Arch, but escaped most of the blast from the two Rockets, and still stands today I believe. "Nibbo" still had his trilby hat and glasses on when we uncovered him and he seemed OK, but he died later.

The V2 Rockets were fearsome things. They carried about a ton of explosive and arrived without warning, as they travelled much faster than the speed of sound. There were always two bangs, the first was the explosion and the second the sonic boom catching up with the rocket.Rumour had it that if you lived to hear the second bang, you were OK, the V2 had missed you.

More than a hundred came over in late October and November, then they gradually decreased, as did the Doodlebugs, and they both stopped coming altogether around the end of March 1945.

The RAF saved Britain a lot of grief by seeking out and pounding the launching sites, until they were finally overrun by our advancing troops.

The Germans surrendered on May 7 1945, and the War in Europe was over at last. May 8 was declared as the Official VE Day for celebrations, but most Londoners couldn't wait, and celebrations went on all over London that night, with singing and dancing by the light of bonfires on the bomb-sites, and the Black-Out no more.

We had a big party at the Fire Station that night, but the Watch on Duty were kept busy with false alarm calls all the evening.

Some time after midnight, things were quietening down, and I was thinking of going home.

When I went out to get my bike, one of the Firewomen on duty in the Watch-Room came out to me in a state of great excitement. It was Nobby Clark, a nice friendly Firewoman who I'd known ever since I joined the Station in 1943.

She told me that the Watch-Room Girls had managed to persuade the Company Officer to let them ride the Pump on the next call.

There hadn't been any false alarms for a while, and the Girls were getting jittery in case the Officer changed his mind, so they wanted me to pull a street alarm on the way home, preferably the one on Canal Bridge which was straight down Old Kent Road from the Station.

I'd never done this before, but I thought it was a good idea, so I agreed, and off I rode.

Most of the revelries had died down by then, and there was no-one about, but many windows were ablaze with light. The Fire-Alarm was on the corner of the road I would turn down on my way home.

I left my bike round this corner and went back to the alarm. After Checking I was alone in the deserted road, I quietly broke the glass with my elbow and pulled the lever, then stepped back round the corner.

A couple of minutes later I heard the clanging of Fire-Bells, so I crossed the road and stood in the shadows where I could see all the action.

In the distance, coming down the straight stretch of road with Tramlines, I saw two sets of headlamps.

Our two Fire-Engines were approaching a bit slower than usual, and somewhat erratically.

As they got closer I heard the sound of singing as well as Fire-bells, and I saw the figure of Nobby Clark standing beside the Officer in the open cab of the leading Fire-Engine. She was lustily clanging the Fire-bell, her hair flying in the wind. Behind her I could see Firewomen and Firemen singing as they hung on to the rails either side of the ladders.

With that, I beat a hasty retreat before I was seen, and rode home.

The Girls had got their wish, and I thought they richly deserved it.

Next day was the Official VE Day, but I was a bit late getting up. In the afternoon, Sid came round and we went over to Picadilly-Circus, which was absolutely packed with celebrating people, mostly in uniform. We gave up our idea of going through the park and up to the palace, it was far too crowded.

Instead, we made our way to Trafalgar Square where we joined in the celebrations, singing and dancing with the revellers till the small hours.

I lost count of how many "Knees-up Mother Browns" and "Okey-Cokeys" we did. Everyone was so happy. It was a great time to be alive. I don't remember how I got home that night, but I woke-up in my own bed next day, so I made it OK.

I got my letter of discharge and was stood down from the NFS on 31 May, when I handed my uniform and all my gear in.

I was glad that the war was over of course, but I was left with a sort of empty feeling after being a part of things for so long.

A little while later we heard that the King and Queen were going to stop at the "Dun Cow", a well known Pub near our Fire-Station in Old Kent Road, on their tour of the bombed areas of South London.

Sid and I went there on our bikes, and sure enough the Royalty turned up.

It was a sunny day, and they were in a big open car, the King was in Naval Uniform,and the Queen was dressed in pale blue. I don't remember if the two Princesses were with them, but there was only one escorting car and some Police Motor-Cycle Outriders.

When the car stopped for a few minutes, the little crowd surged forward, cheering. There were only a few local Policemen there. The King and Queen were smiling and waving, it was all very informal and friendly.

Japan surrendered in August and we had another celebration for VJ Day. The war was really over now, although austerity and rationing were to carry on for a few years yet.

As for me and my friends, the war had turned us into adults early and we'd missed our teenage-hood. I had a lot of catching-up to do, and with Call-up and National Service still looming ahead, it would be a few years yet before I could really get on with my life.

The End.

Contributed originally by richard_storer (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Boy's Wartime Memories of London and Dorset

Richard Storer

London

I was born in Hampstead, London in 1933 and though I was too young to understand the concerns and worries that my parents and other adults in the family must have had during the period leading up to the declaration of war, some of it must have been absorbed by my imagination as I have clear memories of digging a large hole which was to be an air raid shelter in our back garden. I don't suppose I had any idea of what an air raid shelter was for but it must have been clear to me that it was something that was going to be needed and that digging a hole was the initial requirement. I also remember that I was careful to dig my hole with a shelf cut into the soil on one of the sides so that I would have somewhere to put a bottle of Heinz tomato ketchup. Presumably I must have overheard talk of stocking shelters with supplies of food and tomato ketchup was obviously something that I did not want to be without.

Amongst my other memories from those times leading up to the war are those of Walls ice cream men pedaling their tricycles round the streets ringing their bells and, when stopped, handing over water ices which were contained in a cardboard tube of triangular cross section. You had to push the ice up from the bottom of the tube and I can still taste the soggy cardboard that used to end up surrounding the business end of the ice. I also remember coal being delivered to London houses by horse and cart, being taken to have afternoon tea at Selfridges and the wonderful model train layout that ran all round the first floor in Hamleys' Regent Street toy shop.

Dorset

An aunt of mine had a house in the village of Chideock in Dorset and I was sent out of London to live with her just before the war started. I was not really aware of why I had been sent to out of London as the move was just like the other Dorset holiday visits to my aunt that had gone before. The reality of what was happening in the world was made a bit clearer when Hobbs, who looked after my aunt's garden, told me on the afternoon of 3rd September 1939 that we were at war with Germany. Hobbs must have been dismayed at what was happening in Europe as he had been lucky to survive the whole of the First World War spent in the trenches of France and Flanders. Many others who served in the same trenches never came home to their Dorset village homes.

To begin with, nothing seemed to alter in West Dorset. We still went down to the beach. The beach huts remained in use and the cafe still dispensed trays with pots of tea for the grown ups and ice cream for the children. Slowly, however, things started to change. I remember one day when we were on the beach that a camouflaged aeroplane, friend or foe I know not, came hurtling in from the sea just feet above the wave tops and lifted up to pass over our heads and disappeared inland along the deep valley that led to the village. Eventually the cafe was taken over by the Home Guard and the cart track that we used for walking to the beach was rebuilt in concrete so that a continuous stream of lorries could wend their way to the shore to be loaded up with pebbles and then return inland with their cargo along the other tarmac road to make even more concrete to be used in the war effort. That concrete track still exists and, though a bit cracked here and there, is still serviceable and in daily use. Sitting on the beach we would sometimes see depth charges or other explosives erupting in the water further out to sea in the Channel. One evening we watched a dog fight by some aeroplanes in the sky just off the coast, eventually seeing one come down, trailing smoke as it dived seawards and followed by a lone parachutist who landed in the sea off Lyme Regis. We subsequently learned that he was a German.

At the beach, the mouth of the valley between the cliffs was eventually filled with a huge wall of scaffolding and the beach itself was dotted with concrete cube obstacles about five feet square and with sloping tops. The bits of low cliff that did not pose a major obstacle to an invading army were wired off and laid with mines. Post holes were dug in the roads leading from the beach and also along the main coast road that ran East West through the village. These holes had removable caps and, at the side of the road, were stored lots of substantial, iron, antitank constructions which would be slotted into the uncapped holes once an invasion seemed imminent. I also remember, and looking back I cannot believe how naive we must have been, that my cousins and I ventured down to the beach and set up watch on the night of the full moon that had been identified by the press as the likeliest time for Hitler to try and invade England. Thank heavens he never came.

Though I remember having been given a gas mask I never remember having to carry it with me in one of the square, brown, cardboard boxes suspended by a bit of string over the shoulder that one sees so often in archive film of the period. I do however remember that another aunt of mine living in London had a shelter bearing some government minister's name ( not Anderson ) which stood in the middle of her front hall and resembled a large rectangular dining room table made out of solid metal of some kind. The idea was that anybody sheltering underneath it would be protected from collapsing walls and other falling rubble should the house be bombed. This aunt's shelter was always draped with a large table cloth and usually sported a pot plant or a vase of flowers placed carefully in the centre. This shelter was never called into service but, towards the end of the war, a V2 rocket did land two houses away down the street and the family portrait of "Uncle Sam" (circa 1820) was damaged by flying debris. My grandmother never forgave " that dreadful Mr Hitler" for the outrage.

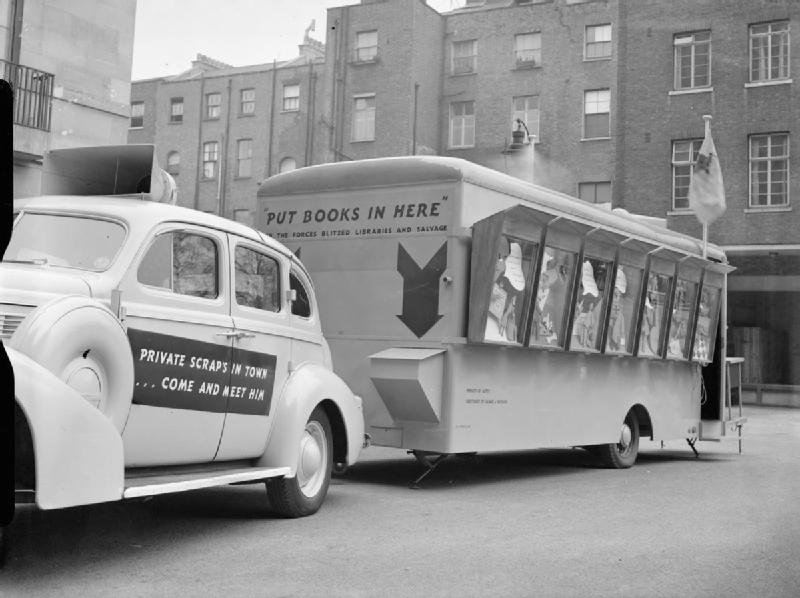

I was a wolf cub whilst living in Dorset and I remember on a couple of occasions being put on an open lorry with Arkela and the rest of the cub pack to take part in processions through the local town of Bridport during Spitfire Week or Salvage Week or some other week designed to help the war effort. All sorts of metal was collected at this time; aluminium cooking pots to make aeroplanes and all the iron railings were removed from the tops of the low brick or stone walls which had commonly fronted many houses before the war started.

When rationing was introduced my aunt adopted what, in retrospect, I now realise was a very sensible routine with the rations for the household. She put to one side all the butter, sugar and jam that she required for the week's cooking and, from what was left over, everybody was then issued with their own personal tea time rations for the week. The top of the tea trolley became covered in pots, jars and other containers each containing the jam, sugar and butter belonging to the child whose name appeared on the container label. We were at liberty to eat the lot at Monday tea time if we wished but we would not be issued with any more until the next week's rations were distributed. It was a learning exercise which taught us many disciplines: self control, fair shares, planning, frugality, contributing to the common good etcetera. Like many families during the war, we augmented the shop bought rations by keeping chickens, ducks and rabbits and by growing lots of vegetables.

I remember soldiers being billeted in the village. We had a couple of Highlanders with us in my aunt's house and a piper used to play through the village in the mornings presumably to collect the scattered Scotsmen all together before they went off to their daily duties. I also remember Royal Welch Fusiliers with the black flaps sewn to the collars on the back of their khaki battle dress; flaps which the regiment had worn for hundreds of years ever since a previous Colonel had decided that his soldier's tunics needed to be protected from the white powder on the pigtails of their wigs. At a time when the country faced the ultimate challenge for survival, only the British could go to war in the twentieth century believing that it was still important to protect their battle dress from wig powder. Long may such traditions endure. The only 'action' that came anywhere near us in our Dorset village was one night when a German bomber, presumably fed up and wanting to go home, just jettisoned his bombs which landed harmlessly on the hillside on the outskirts of the village but provided a topic of conversation for several weeks afterwards.

In 1942 I left my aunt's home in Dorset moved to Suffolk to join my mother and stepfather.

After the war ended in 1945 I went back to look at the home where I had been born in 1933. The house where we had a flat was still there but a nunnery that was 2 door away had been bombed and apparently some of the resident nuns were killed. I also went down the road and round the corner to take a look at the nursery school that I used to be taken to in the mornings. As I walked towards it, memories of the smell of Jey's Fluid which was liberally used in the toilet came back to me and I wondered if the smell would still be there. The smell had gone and so had the nursery school, bombed like so much else in London.

Contributed originally by saucyrita (BBC WW2 People's War)

Rita Savage (nee Atkinson)

A child’s view of the war.

In 1939 I was nine years old and living in Peckham, London S.E.15. It was 3rd September 1939 and I remember sitting on the back steps that led into the garden listening to my mum and dad discuss the advent of the Second World War. My parents had of course lived through the First World War. My dad served in the Army along with his brother and father; they were all in the same regiment I am told. My uncle Ernie was killed in France but my dad and my grandfather both survived.

This particular day as I sat on our back step, dad had switched on the wireless and we heard our then Prime Minister, Mr. Chamberlain broadcast that we were at war with Germany. A few minutes later we heard the distinctive wail of the air raid siren and I remember thinking that we were all going to die on this the first day of the war. All the tales I had been told about the First World War came back to me and I was terrified. My sister Doris would be about sixteen years of age then and she seemed to take it in her stride. My brother Brian was only about four years of age and too young to understand.

We didn’t have an air raid that day of course, the all clear sounded straightaway. We were simply being prepared for what was to come.

The first few weeks of the war went by and nothing significant happened that I was aware of except all the schools were closed in London where I lived anyway. I suppose all the teachers eligible were called up or they enlisted in our armed forces.

I got over my initial terror and enjoyed the freedom from school which I didn’t like very much anyway.

The next thing that happened was for me a very traumatic one — gas masks! I remember all the family going along to this large building, probably the Town Hall, I can’t remember now and waiting in a queue to be fitted for these horrible looking contraptions. My mother was very worried about my little brother Brian thinking that he would act up and cause a fuss. She didn’t worry about me; I was older and never made a fuss about anything.

Wrong! When it was my turn I did more than make a fuss, when they tried to put the mask over my face I remember becoming hysterical. I couldn’t bear to have my face covered; I have been like this all my life. Claustrophobia is the word of course but I didn’t know that at the time. My brother on the other hand wouldn’t take his off he wanted to keep it on. We were supposed to practice wearing these masks on a regular basis and I would always disappear and go into hiding.

My parents decided to move house at that time, only into the next road. Later on in the war the house we had moved from was flattened taking with it the house next door where some of our friends lived. There were five children in that family and they along with their parents were all killed. The house we had moved into was never bombed and had we known it then of course we could have stayed there throughout the war and gone to our beds to sleep every night and not to the Anderson shelter in the back garden.

The war had been going for about a year by this time with no air raids and the schools were beginning to open their doors once more when the blitz on London started in earnest.

That first air raid was a daytime one, I remember I was playing on the front with my friend and when I heard the siren I immediately ran to my mother who at the time was talking to someone at our front door. She hadn’t heard the siren at first and she was very cross with me for interrupting her, children were indeed seen and not heard in those days. I was forgiven however once my mother realised what was happening. We only just made it to the Anderson in time before we heard the enemy planes overhead and the bombs dropping all around us. My mother was in a state because my sister and my dad were at work. My dad and sister were all right thank goodness but they were both very shaken when they eventually arrived home.

That night the raids started in earnest. We spent every night after that in the Anderson shelter or as I will tell you later in other shelters. We would lie awake at night listening to the noise of the falling bombs and the noise of our ack ack guns and wonder if our house would still be standing in the morning.

My brother and I would lay either side of our mother and cover her ears with our hands. My mother was a complete nervous wreck after a few weeks of this bombardment of our city.

In retrospect I realise she was so afraid for us her children. In later years when I had my own children I would think back to these terrible times and only guess at her agony of mind and her fear for us her three children.

One day the lady next door said they were going away for a little while and as their shelter was a bit more comfortable than ours we could use it if we wanted to. So that evening off we all went with all the paraphernalia that was needed to take down the shelter with us, i.e. flasks of hot drinks, candles, matches, a torch etc, not forgetting the gas masks of course, making our way into next door’s garden and their shelter. When the door was closed we were completely sealed in and it was padded out so the noise wasn’t so horrendous. When we were settled later on and it was time to try to get some sleep dad blew out the candles. Fortunately for us my brother started to cry and complained of tummy ache so dad tried to re-light the candles but they just wouldn’t light. It was a few seconds before my dad realized they wouldn’t light because there was no air coming into the shelter. We got out of there pretty quickly and made our way back to our own shelter. But for Brian, my little brother, we could have all suffocated.

We next tried the cinema at the end of our road — I remember it was called “The Tower” — they had cellars underneath that were opened to the public at night to use as a shelter. We had quite a job to get somewhere to sit. They had these wooden benches covering the floor space and mum tried to make up beds for us children underneath these benches on the floor. We didn’t hear the noise so much but to my mother’s disgust a few of the older men sitting nearby every so often would spit on the floor quite close to where we lay. We were only there one night my mum wouldn’t go back again.

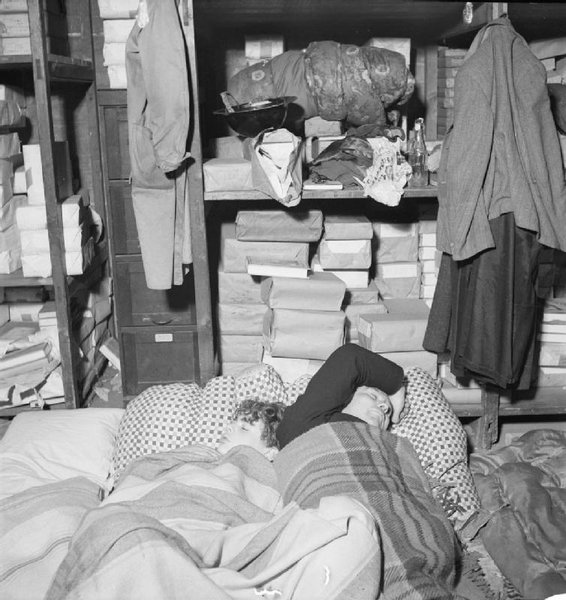

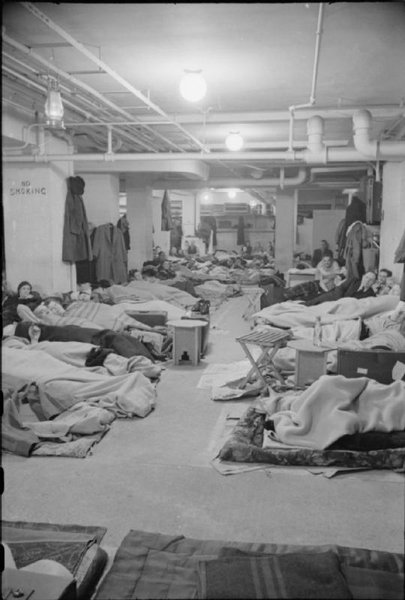

The next night mum dragged us all to the underground railway, the Oval at Kennington, the trains were not running at night and people made up their beds on the platforms. We thought we were early but when we got down there we had to step over bodies trying to find somewhere for ourselves. We had to give up as there was no room and we went back to our own shelter again. We heard later on that just after we had left the Oval a bomb was dropped at the entrance. Our guardian angel must have been watching over us that night.

My parents decided that we children should be evacuated as so many of the children were. Mum sewed our names in all our clothes and off we went to the railway station, I can’t remember which one it was, probably Euston, where daily trains would come in and children were packed in, gas masks around their necks, saying their goodbyes to parents left standing on the platforms. At the last minute mum couldn’t let us go — what a decision for a parent to have to make, not knowing where your child was going and if they would be treated well and looked after properly. This was probably just as well since my mum wanted my older sister to go too in order to keep an eye on us. This would not have worked of course for one she was seventeen and for another when the children got to their destination families were more often than not split up. My mum didn’t know this at the time though. So once again we all went back home.

I remember one morning in particular, we hadn’t been up from the shelter for long from the night before and the wail of the siren started up again. My mum and dad sent us children straight back to the shelter. Incidentally we had a dog called Trixie and as soon as she heard the siren she would make straight for the shelter, she was always in first. Anyway, the raid started almost before the siren had ended and bombs were dropping about us and our sister and parents were trapped in the house, they dived under the kitchen table for some protection. We children and our dog clung together praying that the rest of our family would be safe in the house but we both thought that they would surely die.

By this time my mother was so distraught she begged my father to give up his job so we could all move away from London together as a family. We had endured months of these terrible raids. My father was a milkman with the United Dairies and he would come home from work in a terrible state, collapsing into a chair and burying his face in his hands and really cry, at the same time trying to tell us how he had gone to deliver milk to his customers in the East end of London only to find whole streets wiped out and people he had known for years, laughed with, had cups of tea with, were all killed or made homeless their houses just smouldering rubble.

One night Brian had a very high temperature, he was prone to fits when he was a young child, my mum wouldn’t leave the house for the shelter in case it did him some harm so we all huddled under the stairs for some protection.

Later on that night the air raid warden knocked on all the doors in our road informing us that we had to get out of our homes because it was believed a land mine had been dropped at the end of our road. Mum would not leave, she said that if our number was up, so be it. She was not going to take Brian outside. Fortunately for us it turned out not to be a land mine after all just an unexploded bomb which was eventually defused by the bomb squad.

After this my dad did not need any persuading to leave London, he was ready to go. But where to! My sister Doris had a boyfriend called Ron who had been deferred from the armed forces because he was an electrician and had been sent by his firm to Stoke-on-Trent where he was engaged in electrical work at a munitions factory. He got us rooms in a house in Boughey Road, Shelton where he was also lodging.

The day we actually left our home in London is one I shall never forget because of the trauma and upheaval this move caused us. My mother had a boarder called John living with us and I remember him very clearly. He was always very kind to us children. He was a pharmacist and we thought of him as an adoptive uncle. He promised to take care of our dog and all our belongings until we could send for them. We also had a cat called Tibby and we all loved her very much but she was old and no one else wanted her so we had to say goodbye and sadly dad took her to be put to sleep. We also had a rabbit, pure white she was and so sweet. What a wrench to have to part with her as well, particularly for Brian who was only six at the time and he thought the world of her. We gave the rabbit away to friends who promised faithfully to look after her.

We packed everything we could carry of course and we were finally ready to go. All our neighbours came out to say goodbye and wish us luck with promises to keep an eye on our house and especially the dog. When I think back now, what wonderful neighbours they were, later on in my story they all rallied round and helped John with the removal of our furniture and belongings including Trixie, our dog. Anyway we eventually left and caught a bus taking us to Euston Station to catch the train for Stoke-on-Trent. As the bus moved slowly along Peckham High Street we heard the wail of the siren and the drone overhead of enemy aircraft. All of a sudden we heard an explosion and everything seemed to shake; we later heard that a bomb had been dropped not far behind us, if this had happened a few minutes earlier we would probably have been killed.

We arrived at Euston Station shaken but all in one piece and stood on the platform with our suitcases around our feet waiting for the train to take us out of the misery of living in wartime London which was once our home. The train was late and when it did arrive it was packed mostly with service men. We had to sit on our cases in the corridor of the train and we moved very slowly forward out of London and towards the Midlands. It was a terrible journey, the train kept stopping for no reason that we could see. It seemed to us children that we were on that train for hours. We finally arrived very tired and despondent and set foot for the first time on Stoke Station. We were met by Ron, Doris’s boyfriend. It’s such a long time ago now over sixty years, I cannot remember how we got from the station to Boughey Road, perhaps we walked. Anyway we arrived eventually and found that our landlady was very nice and very welcoming. We had the front bedroom upstairs, it contained a double bed which Brian and I shared with mum and dad and a camp bed at the foot of the double bed for Doris. We were okay with this arrangement since we had all been cramped together in the shelter in London. It was wonderful to be able to go to bed and go to sleep, what bliss! We did of course hear the siren some nights but we ignored it and stayed in bed, after what we had experienced the raids here were mild. There had been bombs dropped here locally before we arrived. The Royal Infirmary was hit and also a house in Richmond Street, Hartshill, I think it was Richmond Street anyway.

My mother, after a lot of tramping about in the Potteries, finally found a house in Princes Road, Hartshill which had not been lived in for ten years. In those days houses were all rented, no one bought a house, unless you were well off anyway. My poor mother had to scrub that house several times before we could move into it because of all the grime that had accumulated over the years. We had no choice really, we had to have this house, no other landlord would rent to us because we were from London and it was believed that Londoners did not stay long in the Potteries it was too quiet for them! Everything was so hard to get in wartime, when we moved in we had no electric or gas, we had to use candles for light and in the kitchen was a black leaded fireplace with an oven at the side which mum had to use until we could get a cooker. We did get an electric cooker eventually but if it had not been for Ron, who also came to live with us, we would not have been able to use it because the electricity board had no one they could send to install it. Ron fixed all our electricity problems, we were very lucky. Getting coal to heat such a large house was a very big problem, we burnt anything we could on that fire and in the evenings we all sat huddled together round it. We couldn’t get curtain material so we had to have black paper up at all the window because of the blackout.

The day when the removal van with all our furniture and best of all our dog eventually arrived was wonderful. The removal man wanted to buy Trixie from us he couldn’t get over how good she had been on the journey, never attempting to run away. She knew he was bringing her to us because she was with all our furniture and belongings in the van. We never went back to London after the war but made our home permanently in Stoke-on-Trent.

I would like to say to all those people in London and other towns who were so cruelly bombed how much I admire them for sticking it out. They were a lot braver than we were.

Written by Rita on 4 December 2003

Contributed originally by Stockport Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People’s War site by Linda Paton of Stockport Libraries on behalf of Henry 'Rob' Farley and has been added to the site with his permission. He fully understands the site’s terms and conditions.

It was tough on parents to hear the staccato, impersonal declaration of War with Germany back in 1939. To an eight-year-old, vaguely listening in on the radio, it did not immediately register as much more than a prospective Cowboys v Indians shoot-out skirmish. I probably then was concerned with swapping my much-thumbed Beanos and Dandies for more seriously adult literature such as Hotspur, Adventure and Champion. No notion occurred of the impending absence, probably forever, of pear drops, Mars bars, oranges or most forms of red meat other than ox hearts, liver or horse, or the recognition of ration books, ARP wardens with their brass bells and tin hats, blackouts, artillery batteries at street junctions, and the threat of blood spilt. With the early sight of hurricanes and spitfires in spiralling formation across the skies and the wail of sirens, the tempo of life changed even for childish minds. New words became part of the day to day vocabulary - incendiaries, camouflage, barrage balloons, searchlights, shrapnel.

We were living on one of many mid-1930’s housing estates, every developable inch occupied by terraced and semi-detached houses with neat gardens. All the streets and avenues were named after exotic West Country locations holding images of white- horsed waves rolling in and constant sunshine. Positioned in the general vicinity of Northolt aerodrome, the area was bound to become an inevitable target for random, aerial bombardment. For the adults, this prospect must have struck terror in the heart. For a child, like me, it took more than a while for the perils implicit in the sound of the siren to dawn. We lived in a compact, terraced house near the beginning of the road. The Browns were halfway down it in a semi-detached. Unusually for the neighbourhood, one realised with the benefit of hindsight, Mr. Brown had his own private business in the construction world. Adelaide was the daughter, roughly my age, but never one of our gang. Female, to start with, and far to pert and porcelain-like for our re-enactors of the fastest gun in the West. And at football, one could scarcely contemplate a girl in goal.

As we all edged older month by month, the pattern of our lives changed, apart from anything else, in terms of the nature of hostilities. Still, there were the odd fighter planes, adorned with swastikas, machine guns spewing, and bombs of increasing venom reeking havoc in one community or another. Then arrived the era of the silent destroyer, the V2 and, of course, the doodlebug. In its case, you were safe enough whilst you could hear the riveting bass drone of its engine. There was an immense consciousness of the slow stutter before it finally petered out.

Most houses in our street had resort either to an indoor Morrison shelter or a self-erected Anderson in the garden. The only locally, well- publicised exception was at the Brown menage. Thanks to the dexterity and inclination of Brown the elder, they had a serious underground bunker backing on to the alley at the rear, a great haunt, anyway, for shrapnel seekers. Dutifully, at that stage of the war, every evening as a family we retreated with some Irish friends to our cosy, familiar Anderson. We were armed with Thermos flasks, knitting needles, wool of many hues, a galaxy of Irish stories and protective sprinklings of holy water.

On this particular, pre-dawn morning, tucked up in overcrowded comfort, we were shocked awake by an explosion that rocked the foundations. In the land of nod we had no presentiment that the doodlebug’s engine had cut out seconds before. Almost as if Hitler himself had specifically schemed it, the bomb landed directly on the Brown’s architectural bunker. The conscripted air raid wardens were quick to scour the debris strewn over our beloved street for much of its length. Our own house, on cursory inspection, had most of the ceilings down, doors blown off, bizarrely both inward and outward, and, I clearly recall, shards of taped glass like mottled darts piercing my parents’ otherwise intact wardrobe. A headcount revealed that, with one exception, everybody was groggily on parade. The one exception was Adelaide. Probably because it was at least as comfortable as the house, as a matter of rote, the Browns always spent their nights in the bunker - now a shattered heap of reinforced concrete, Middlesex clay and Ruhr metal. On this night, the hand of fate had intervened and for some reason the Browns had elected to sleep in their own beds. In the cool of the morning, the shrapnel still too warm to covet for posterity, rummaging around in the Browns’ downstairs dining-room rescuers found Adelaide still in her bed. Thanks to the angels, she proved as right as rain save for the odd, trophy scratch acquired in her descent through the collapsed ceiling. Indeed, I am certain she bedded, like a sainted heroine, the following evening along with all the other bombed-out families at the temporary Church Hall refuge.

It must have been shortly after that too close to call incident that I first recognised inside myself, an ominous awareness of my own mortality. Perhaps it was no more than a symptom of approaching adolescence, but I began to shake with fear whenever the syncopating rhythm of the air raid siren sounded. The all clear gave unmitigated relief. But from then on, I abandoned the Anderson at the end of the garden and knitting scarves, preferring to shake alone indoors under the stairs alongside the brooms. The fear of fear made me crave my own company.

It was doubly good fortune that the war from our point of view was veering toward its close. The skies were now full of waves of Wellingtons and the like, setting off on missions that flattened Dresden, Dusseldorf and Frankfurt. The newspapers dwelt less on our accustomed, domestic ills, but vividly portrayed the daily advances by the Allies ultimately on Berlin. Likewise, on the radio, although these commentaries were interspersed by such respites as Workers’ Playtime, the Andrews Sisters and Tommy Handley.

Almost as imperceptibly as we had moved on to a war footing, the need to celebrate peace with vigour began to ascend the priorities. VE day followed with eager anticipation by VJ Day. Impromptu street parties gave outward recognition to immense relief from accumulated tension. It is hard to be precise, but I suspect that it was in that mood of rampant euphoria that Adelaide gave a party in her house and I was asked to it. Why I was asked was never entirely apparent. I was not a member of her contemporary clan and no other members of my gang were invited. The only logical reasons to ascribe were that I lived in the same street, was near the same age and wore trousers. Peering back now through the decades, that party probably set me on the path, in modern parlance, of an instinctive, natural net-worker. That word would not have been coined in the late 40’s, when apart from having a vague, historic link to our hostess, Adelaide, I started off by knowing no one else. And no one else knew me. Unfamiliar skills needed to be rapidly mustered to combat a frustrating sense of isolation. Putting on my interpretation of an Alan Ladd swagger, I started off with mannerly greetings to two of the girls, who had arrived more or less at the same time in a cloud of mother’s eau de cologne. They were more immediately accessible, and distinctly more attractive a prospect, than the other boys Brylcreemed up and puffing away on Woodbines. Very early on, I discovered that the art of networking largely revolves around asking questions and having a fertile memory.

Clearly, I did not witness her rescuers disentangle a tousled haired Adelaide from the doodlebug debris on that fateful night. But one could imagine her pristine, pink skin and her dusty, rosebud mouth. Here, some years later, that child had metamorphosed into a Grable-like dream. Lithe with excited, blushed cheeks, full, mobile lips and an air of confidence heralding imminent adulthood. She was the shape of things yet seriously to come. Needless to say, in no time at all, Adelaide had a team of admirers queuing up. All much bigger than me, including Adelaide.

The only recollection I have of music, as such, was the soft, sugary lap of Hawaiian serenades. Without contradiction, there was no form of alcohol in the midst and we had to rely on copious draughts of Tizer to fire us up. All the girls wore the seamed nylons of the day, almost certain to be laddered before the evening was out. Someone was periodically switching the lights on and off, probably Adelaide herself. Several times, Mr, Brown, perhaps perturbed by moments of spasmodic stillness put an anxious head around the door. There is no doubt, but that the assembled hormones that evening, maybe for the first time in any of our lives built up in to radical overdrive.

I never saw or heard of Adelaide again or any of her fellow guests. Faces passed like proverbial ships in the peacetime night. The only thing we all had in common was that we had lived through the Second World War and had survived it to tell our tales. We also had pending, the obligation to weave out our future destinies in the wild, wide world. I wonder what happened subsequently to Adelaide and her party guests during the intervening decades. There must be a yarn or two to emerge of setbacks, sadnesses, victories and enduring joys.