High Explosive Bomb

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Bloomsbury, London Borough of Camden, WC1H 9SH, London

Further details

56 20 SW - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by Franc Colombo (BBC WW2 People's War)

ENGLAND PART FOUR

When we got ashore we were met by nurses and volunteer women who made a fuss of us then took us to a big marquee given tea and sandwiches then to a room where our pay book was checked then given travel warrants and told to report to our depot. I arrived at Hounslow in the evening, after settling down I phoned my father to say that I was safe he was pleased to hear from me because by that time he heard the news of the evacuation, in due course the remainder of the battalion arrived, I learnt that quite a few were killed, wounded or missing, fortunately my friends where O.K, finally I met up with my officer and he wanted to know what happened to me. Soon as we were refitted we were posted on the Isle of Wight, we were expecting the Germans to invade, we had few weapons one rifle between two men some just had pitch folks or pick handles, bit by bit we received new weapons, by this time the battle of Britain started, we heard that London and other cities were being bombed, we had our share one bomb dropping on the cook house causing many casualties, luckily it was not meal time.

Our next move was back on the mainland doing training and route marches of twenty miles. I was due to go on leave but before going I had to see the company commander who told me that being Italy declared war on England and being that I came from an Italian family there was the possibility that if I was captured I could be shot therefore I could transfer to a non combat unit I told him that England was my country. When I got home I told my father about it and he told me that I should fight for my country, he also told me that Bastiano and Armando had been interned and he was trying to get them released.

Armando was interned because his mother Fernanda never liked England and sent him to an Italian school and was registered as a fascist. I remember one time when I visited Jinnie and fernanda was there and she said that she could not understand how I could go and fight against the Italians, I told her that they declared war on my country and if I came up against them so be it.

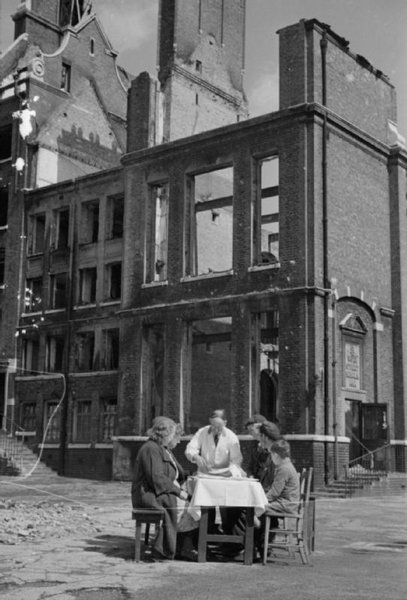

When I went round London I saw the destruction the bombers made, where houses and shops stood there was just a gap and rubble, fortunately round Edgware road they had no damage. In the evening I would visit my friends and we would go to the west end, for a drink it was strange to see so many uniforms and nationalities, many times we had to take shelter because of the raids. While I was on leave I contacted the red cross to see if I could get a message to Tinuccia, I was able to send a card to say that I was well, later we were able to correspond more frequent. Shortly after returning from leave we moved to Newbury, we were billeted on the racecourse just on the edge of town which suited everybody, Newbury was a friendly town and had quite a few places for entertainment.

While we were there Capt. Hill told me that he was being posted to another battalion and would I go with him, I told him that I had applied for a transfer to the airborne division and therefore I would not join him. On the 13th Dec. 1941 we went to Invarery Scotland for combined operation training, we had to live on board a ship in the middle of the lake and sleep in hammocks, we had some fun trying to swing into them but we soon got the hang of it, then we had to learn how to scramble up and down the side of the ship by a rope ladder into an assault craft, in the beginning we found it hard going but after a few times we were going up and down like monkeys. The exercise was landing on the beaches.

We had Christmas dinner with a pint of beer on the ship the rest of the day was our own. The following day the C. O. thought it would be a good idea that after all that food and drink we consumed the previous day we should sweat it out, so we were put ashore by platoons and do a thirty miles march finishing going up a steep hill which terminated on top of a cliff and scrambling down a rope and back to the ship . When our training was over we returned to Newbury, by this time I was receiving letters from Tinuccia, few and far between but at least I knew she was alright and that the feeling for each other was the same, in her letter she told me that one of her cousins had gone to Tunis and that she gave her some letters for me and that if ever I was there I could pick them up.

Our next move was to Camberly, in between manoeuvres we had a visit by King George the VI. I remember that it was a very cold day and light snow on the ground, it was decided that he would come and see us doing training in a field, our company was chosen to do physical training, we arrived at the field in our greatcoats an hour before he was due. When he showed up we removed our greatcoats and just in shorts and vest started to do P.T. when he saw us apparently he was annoyed and told the officers that we should return to our billets given a hot drink and a rum ration.

In April 1942 we were on the move again back to Scotland but this time we were going to walk, we were supposed to be chasing a retreating enemy, we did 130 miles in seven days. We arrived at Stops camp 5 miles outside the border town of Hawick. Contrary to the reputation that the Scots were mean we found them to be the most generous and kind hearted people we ever met, the hospitality of the habitants of Hawick was overwhelming, every man had a household to which he could go when he was in town and be sure of a meal, my friend Frank Vincent and I were taken in by mr. and mrs Nayler and treated as their sons.

Soon after settling down the anti tank platoon was formed I asked to be transfer to it because I was in it when we were in Shornecliff, soon after I was promoted to lance corporal. The training was hard but we were fit, one part was that with my section of 7 men we were taken in the glens miles from anywhere and had to live on the land for 48 hours making our way back to camp using a compass, in the morning we stopped at a farm to ask for some water to make tea, the farmers wife asked us what we had been doing, we told her that we had been out all night she invited us in and gave us a full breakfast and sandwiches to take with us, we finally arrived back in camp, we were not the first but we were not the last.

By this time I was made full corporal in charge of a gun, then came news that we were going on embarkation leave, the train to London did not leave till midnight Mrs Naylor insisted that Frank and I would have dinner with them and made us sandwiches for the journey, the train was packed and we had to sit in the corridor all night. Finely I arrived home and I was told that with fathers intervention Basil and Armando were released from interment. Soon after Armando was called to join the army. I visited all the family because I knew that it would be a long time before I would see them again, I shut it out of my mind that I might never return.

Then I visited my friends and as luck would have it they were also on leave therefore it was an occasion for a celebration and going to the West End and having a good time, one night we went to see Gone with the Wind, it was the rage then. All to soon leave came to an end I told father that it would be sometime before I would see him again, so I returned to Stobs Camp. We learned that we were moving out in a few days, Frank and I went into Hawick to say our farewells to the Naylers, they were sorry to see us go and wished us luck and a safe return.

The following night 9th of March we marched to the station and boarded the train for Liverpool the port of embarkation.

We went on board and taken to our allotted space, it was cramped but we soon sorted ourselves out and we had our old friend the hammock, then with Polly and some other chaps went on deck to have a look round saw some other ships which would make up the convoy. Our ship was the S.S. Cuba a French ship. The following we were shown our boat stations and boat drill.

Two days later we set sail and taking our position in the convoy. In the bay of Biscay I found it difficult moving around and I was seasick but it soon passed and I got my sea legs, it felt strange because I could move around without feeling the lurching of the ship. The days passed with P.T. lectures boat drills and other activities, several times we had air raids, guns going off every where then we went though the Strait of Gibralter and into the Mediteranian, then one day we were attacked by submarines, they managed to sink two ships, one was a troop ship the Winsor Castle, we were at our boat station and saw her sinking, the destroyers chasing every where dropping depth charges then picking up survivors. The following day we sighted Algiers, it was impressive with its white tall buildings, it looked nice till we landed.

Contributed originally by cambslibs (BBC WW2 People's War)

------------

First I must say a few words about my parents. My father, a classical violinist, had been badly hit by the slump in the British music world of the mid-thirties, and had been forced to look for other work. He started up in business in catering. He was no business man, and my mother, always the practical one, helped to build up "Always Ready" catering service into a quite successful enterprise. Unfortunately the outbreak of war in 1939 caused a sudden collapse in orders, with many contracts being cancelled, and my father decided to close down. He was very keen to get back to his army days of the first world war, but he was too old and unhealthy to be accepted for military service, so he applied for a civilian job at HQ Eastern Command at Hounslow Barracks. He became a clerk in the Army Pay Corps, and later was transferred to an Army depot in Feltham. My mother heard that the depot were having trouble in finding a manager for their canteen for civilian staff, and applied for the job. Her experience with "Always Ready" made her the ideal person, and she was soon very happily employed, coping with all the difficulties of wartime catering.

At the beginning of 1940 I was still at school. I was coming up to my 16th birthday, and preparing to take London Matriculation soon. I went to a small private school which was owned by a retired Indian Army Officer, who couldn't wait to get back into uniform. After a very difficult period of trying to find suitable staff to take over, he suddenly joined up, and said the school would close down at the end of the summer term. I and a few others were left in a predicament; my mother tried to get me into a local secondary school, but because I had not sat for the 11+ (then called the Scholarship) exam., I could not be accepted. There were no other schools of the required standard around, so we decided that I should continue my studies at home with a part-time private tutor, if one could be found. Luckily we found a local teacher who was very ready to augment her low salary by some coaching work after school. She offered to help with English, French, Latin and History, but couldn't help with the Maths. I decided that, with a bit of hard work with the text book, I could manage that subject on my own; Maths had always been my favourite subject and I looked forward to the challenge.

The first few months of 1940 were rather quiet; I don't think I had any true realisation of what must inevitably happen. The first rumblings of Hitler's intentions began - the German war mahine was on the march. We no longer sang about hanging our washing on the Seigfreid Line, and the British and French armies were being pushed back. The Low Countries were invaded. Queen Juliana and the Dutch government came over to London, to continue their fight; the Belgian King decided to make a truce, thus trapping many of our troops who had gone in to help. The full force of the German offensive was directed at France, and our British Expeditionary Force was pushed back further and further towards the coast. Paris fell and I remember feeling a deep sorrow I could not explain, then the final blow came: France decided to capitulate and our Channel Islands were occupied. We held our breath, what had happened to our troops? Several days passed, there was no news for the anxious relatives, but there was a general feeling that something momentous was about to happen. Suddenly fleets of trains began to deliver exhausted soldiers into London, and as quickly as they could be dispersed, more arrived from the south coast ports. The Dunkirk evacuation had occurred and we cheered as though we had won a victory, which in some ways, we had. Many French soldiers had come over from Dunkirk, and General de Gaulle wasted no time in forming the Free French Army. Everywhere in London were groups of soldiers and airmen from our allies, and there was a determination that we would all see it through together. We must have looked a pathetic little lot to the German High Command.

Now we held our breath again. It seemed pretty obvious that we would be the next target for invasion. Even to the mind of a very naive schoolgirl it was impossible for us to survive such an attack. I must have been still a silly child at heart, because I remember being very determined in how I would behave when the enemy arrived. I would never co-operate under any circumstances! I would join an underground movement and fight on! I think my main concern was that, if the church bells rang (the signal that invasion had begun), my parents, working at Feltham, would be outside the road blocks, part of the London defences, and I would be alone inside. As history will tell you, the attack came from the air. The Battle of Britain began. Luckily, I lived in an area well away from the overhead battles, but I saw squadrons flying out and I remember counting the planes back in. They used to fly in formations of six as I remember it, and sometimes when six returned, one of the boys from the back used to break off into the victory roll. I believe that this behaviour was frowned on by their superior officers, but most of them were just enthusiastic boys who needed to let off steam. I still remember the glorious weather of that September, the warm sunshine by day, and the clear moonlight nights which gave the bombers a clear view of London beneath.

Up to this time I hadn't seen or heard an enemy plane, or heard any ack-ack (gunfire), then one night we heard the air raid siren, and we dutifully went down into the Anderson shelter my father had dug into our garden. As we were going in, we looked towards a glow in the Eastern sky. It grew larger and redder, but still no sound of gunfire. We learned next day of the terrible raid on the docklands and when the same thing happened on the next night, people began to ask why we appeared to have no defence. I believe that it had been thought that if London were declared to be an "Open City", that is, with no military targets, it would not be bombed! The next night we heard gunfire. It was only light anti-aircraft fire but it terrified me; however I soon got used to the "Woomp-woomp" which later seemed a very mild sound compared with the heavy stuff that moved into a nearby field. There was also a mobile gun which roamed the streets, and would suddenly open fire with a very loud BANG just outside the house. My father, after two nights in the Anderson, declared that he was going to his bed in the house; he said that Hitler was not going to make him uncomfortable every night, and that if the house came down, he would be on top of the rubble, still in his bed. My mother and I remained in our garden shelter for a few weeks, but as the evenings got longer and the raids did also, we began to have doubts. A heavy rainfall and an earwig crawling into my ear, rather settled the matter - the shelter flooded and we moved out, never to return.

Later in the war we were given a Morrison table shelter, which we used during the doodle-bug attacks, but for the rest of the raids we slept downstairs in nice comfortable beds. I remember that I slept through some of the heaviest raids.

It is hard to describe what life was like during the autumn and winter that year. Every morning we got up, pleased to have survived the night, and just got on with the daily routine. Rationing was beginning to cause shortages in certain commodities, and while we had our essentials, there were always things we felt we needed. Queueing started when any little extra came into a shop, and I remember the rush to the fish shop when a small amount was delivered. It was first come, first served. I don't think the really biting shortages came until much later than 1940. We began to learn the art of make-do and mend. In the meantime my studies progressed, and I felt I should be ready for my exam. next summer. Because I was at home during the day, I didn't try at this time to study in the evenings. I used to try to relax by listening to the radio, but most nights it could be very difficult, owing to the interference when the planes were about. I never knew what caused the interference but wonder now, if it was something to do with radar which I didn't know much about at the time. In the mornings, the garden was often covered in little strips of metal foil, another unexplained thing. My hobby at that time was picking up the dozens of lumps of shrapnel, dropped by the exploding shells from our guns. Occasionally the Germans had dropped a few leaflets which never seemed very interesting to me. I think we must have become immune to noise, as the raids started as soon as it was dark, and went on until daylight; there were very few planes getting through in the daytime, except occasionally on a heavily clouded day.

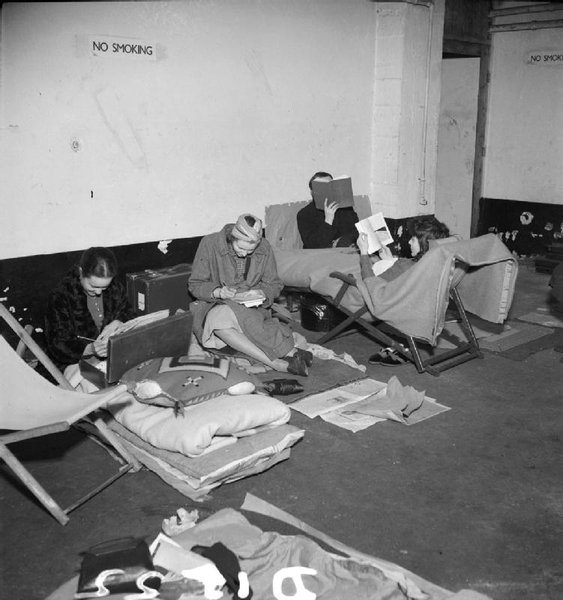

Life in central London went on very much as usual, apart from the clearing up after the night before, the Heavy Rescue squads busy at their often grisly task, the firemen damping down the fires, and everyone being extraordinarily cheerful. I remember going, with my mother, to the theatre during the morning, so that we could be home before the sirens started. Travelling in on the tube with their netted windows, with the little spy hole in the middle, we could work out where the worst raids had occurred during the previous night. The tiles on the roofs would be standing to attention, curtains stripped by flying glass, doors and windows missing, and sometimes just piles of new rubble. The platforms of the deep stations had been taken over for night sheltering, and the walls were lined with bunk beds. No part of greater London escaped the raids, and my western suburb had its fair share. We had various military targets nearby and we felt the occasional "near miss". Sometimes an unexploded bomb arrived, and surrounding buildings had to be evacuated until the Bomb Disposal soldiers had been. On one tragic occasion the bomb blew up, demolishing two houses, and killing the four soldiers who had gone to remove it. Several people died in my area, but none were particularly close, except for one. She had been a fellow pupil at my school, and during one of the rare daylight raids, had gone into her Anderson to shelter; she was killed by a direct hit on the shelter, while her house remained scarcely damaged.

During all this nightly mayhem, my father decided to tour central

London air raid shelters with a group of fellow musicians, "to cheer people up". With the kind of very highbrow music they played, I rather doubt if it had the desired effect, though I believe people did thank them very profusely. Occasionally during a heavy raid, we would stand under our front porch to watch the "firework" display. It was stupidly dangerous, but I have a vivid memory of one night. There were planes caught in searchlights, shells firing up all over, a parachute caught in a searchlight with something very large hanging from it, gently floating down. There were tracer bullets being fired at the flares which illuminated the scene, and there was another parachute which appeared to be throwing out smaller objects as it descended; was this the one they called a Molotov Cocktail?

I do not remember feeling particularly unhappy throughout this difficult period, though I did often wonder whether I would survive.

Somehow we took each day as it came, happy in our togetherness with everyone around us, laughing at the funny things that sometimes happened: the day our next door neighbour turned on her gas cooker, and water squirted from the rings; the night a frantic air raid warden dashed up and down the road, begging people to turn their lights off, when a bomb explosion smashed all the windows and turned the room lights on. There was no TV of course, but we had the radio, and we thoroughly enjoyed ITMA, "Life with the Lyons"(Ben Lyon and Bebe Daniels), Workers' Playtime, and dozens more. Another amusement for some of us was to tune in to Lord Haw-Haw. Much to our government's surprise, he was a huge joke to most young people; they thought he would be bad for our morale. I think the government often underestimated the young at that time!

Christmas came, and "goodwill to all men" must have prevailed, because the raids suddenly stopped, and we had peace over the period.

I believe that this four months of Autumn 1940 was London's finest hour, and I am very proud to have played a tiny part in it.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

By the middle of September, the Doodlebug raids had quietened down a bit. All the launching sites in France were now captured by our troops.

The Germans moved operations farther north to the lowlands, and most Doodlebugs were launched from parent aircraft over the North Sea, so Essex became the direction from which they approached London. Not so many got through however, as the RAF were waiting for them. Those that did make it caused many casualties though, as most people were by now just getting on with their lives and not taking shelter until the last minute.

One Friday morning at the beginning of November 1944, my brother Percy and I were in the kitchen behind the shop having our "elevensies," when there was a huge bang followed by another one like an echo, then a whooshing noise. The ceiling seemed to come down and hit us then go up again, dust flew everywhere.

Shaken out of our wits, we rushed outside and saw that something had dropped at the top of the road. We left the Shop and ran up there to find a scene of devastation. Our first V2 had arrived.

The huge steel framework section of the Railway Arch that formerely spanned the main road was now standing on the ground, with a heap of mangled wreckage behind it. An Electric Train with the letter P on the front was leaning against the brick parapet on the approach to the bridge.

On the road, in the middle of the T junction, the wreckage of a car was burning furiously. I still remember the badge on the radiator, which was about all that was left on the chassis. It read: "Morris Major". Of the driver and any passengers there was no sign. Black smoke from it's burning tyres joined the cloud of smoke and dust hovering over the scene, but we were the only living souls about for the moment, it seemed.

The "John Bull" Pub and all the shops and houses within about 200 yards of the Arch were flattened. The Licensee's Wife, a very nice old Jewish lady, and the Cleaner, who were working in the Bar at the time, were among those killed.

Dad got home from the Market soon after, and the two bereaved husbands, who were friends of his, stayed in the shop with us all day. They were both in a state of shock, grieving their terrible losses.

Many of the terraced houses on both sides of our road near the junction were demolished, including the house where the Girl who later became my Wife lived, but luckily this one was empty at the time.

Many people were not so fortunate though.

There were so many dead bodies that they turned the Manor Methodist Chapel, round the corner in Ambrose Street, into a temporary Mortuary so that relatives could identify their loved ones. We lost quite a few regular customers that day.

By some sort of coincidence, another V2 landed in exactly the same place two Sundays later, just before midday.

Most of the debris from the first V2 had been cleared, and a temporary Bridge of massive timbers erected. This was demolished of course, but there wasn't much more the Rocket could do, as the area was already flattened.

The only casualty I know of was an elderly Gent, a Bookmaker's Runner known as "Nibbo". He'd been standing outside a Pub called the "Ancient Foresters", waiting for it to open.

This Pub was quite close to the John Bull Arch, but escaped most of the blast from the two Rockets, and still stands today I believe. "Nibbo" still had his trilby hat and glasses on when we uncovered him and he seemed OK, but he died later.

The V2 Rockets were fearsome things. They carried about a ton of explosive and arrived without warning, as they travelled much faster than the speed of sound. There were always two bangs, the first was the explosion and the second the sonic boom catching up with the rocket.Rumour had it that if you lived to hear the second bang, you were OK, the V2 had missed you.

More than a hundred came over in late October and November, then they gradually decreased, as did the Doodlebugs, and they both stopped coming altogether around the end of March 1945.

The RAF saved Britain a lot of grief by seeking out and pounding the launching sites, until they were finally overrun by our advancing troops.

The Germans surrendered on May 7 1945, and the War in Europe was over at last. May 8 was declared as the Official VE Day for celebrations, but most Londoners couldn't wait, and celebrations went on all over London that night, with singing and dancing by the light of bonfires on the bomb-sites, and the Black-Out no more.

We had a big party at the Fire Station that night, but the Watch on Duty were kept busy with false alarm calls all the evening.

Some time after midnight, things were quietening down, and I was thinking of going home.

When I went out to get my bike, one of the Firewomen on duty in the Watch-Room came out to me in a state of great excitement. It was Nobby Clark, a nice friendly Firewoman who I'd known ever since I joined the Station in 1943.

She told me that the Watch-Room Girls had managed to persuade the Company Officer to let them ride the Pump on the next call.

There hadn't been any false alarms for a while, and the Girls were getting jittery in case the Officer changed his mind, so they wanted me to pull a street alarm on the way home, preferably the one on Canal Bridge which was straight down Old Kent Road from the Station.

I'd never done this before, but I thought it was a good idea, so I agreed, and off I rode.

Most of the revelries had died down by then, and there was no-one about, but many windows were ablaze with light. The Fire-Alarm was on the corner of the road I would turn down on my way home.

I left my bike round this corner and went back to the alarm. After Checking I was alone in the deserted road, I quietly broke the glass with my elbow and pulled the lever, then stepped back round the corner.

A couple of minutes later I heard the clanging of Fire-Bells, so I crossed the road and stood in the shadows where I could see all the action.

In the distance, coming down the straight stretch of road with Tramlines, I saw two sets of headlamps.

Our two Fire-Engines were approaching a bit slower than usual, and somewhat erratically.

As they got closer I heard the sound of singing as well as Fire-bells, and I saw the figure of Nobby Clark standing beside the Officer in the open cab of the leading Fire-Engine. She was lustily clanging the Fire-bell, her hair flying in the wind. Behind her I could see Firewomen and Firemen singing as they hung on to the rails either side of the ladders.

With that, I beat a hasty retreat before I was seen, and rode home.

The Girls had got their wish, and I thought they richly deserved it.

Next day was the Official VE Day, but I was a bit late getting up. In the afternoon, Sid came round and we went over to Picadilly-Circus, which was absolutely packed with celebrating people, mostly in uniform. We gave up our idea of going through the park and up to the palace, it was far too crowded.

Instead, we made our way to Trafalgar Square where we joined in the celebrations, singing and dancing with the revellers till the small hours.

I lost count of how many "Knees-up Mother Browns" and "Okey-Cokeys" we did. Everyone was so happy. It was a great time to be alive. I don't remember how I got home that night, but I woke-up in my own bed next day, so I made it OK.

I got my letter of discharge and was stood down from the NFS on 31 May, when I handed my uniform and all my gear in.

I was glad that the war was over of course, but I was left with a sort of empty feeling after being a part of things for so long.

A little while later we heard that the King and Queen were going to stop at the "Dun Cow", a well known Pub near our Fire-Station in Old Kent Road, on their tour of the bombed areas of South London.

Sid and I went there on our bikes, and sure enough the Royalty turned up.

It was a sunny day, and they were in a big open car, the King was in Naval Uniform,and the Queen was dressed in pale blue. I don't remember if the two Princesses were with them, but there was only one escorting car and some Police Motor-Cycle Outriders.

When the car stopped for a few minutes, the little crowd surged forward, cheering. There were only a few local Policemen there. The King and Queen were smiling and waving, it was all very informal and friendly.

Japan surrendered in August and we had another celebration for VJ Day. The war was really over now, although austerity and rationing were to carry on for a few years yet.

As for me and my friends, the war had turned us into adults early and we'd missed our teenage-hood. I had a lot of catching-up to do, and with Call-up and National Service still looming ahead, it would be a few years yet before I could really get on with my life.

The End.

Contributed originally by thewilliam (BBC WW2 People's War)

September 1939

I was nearly six years old when war was declared. At this time my family was living in a gloomy, three floored terraced house in North London.

My family consisted of my father and mother, two sisters and a brother. My siblings were considerable older than I, my youngest sister being eight years older. My parents were in their late forties, in those days rapidly approachng late middle age. My father worked as a Coal Agent. Hs job wsa to travel the district on his bicycle collecting payments for coal supplied by his company.

On this day in September 1939, my parents are standing listening to one of or few luxuries, a wireless set. This is a large device, perhaps two feet high, covered in a honey-coloured veneer. When the tuning knob is turned it makes, to me, all kinds of exciting howls and sqeales as remote stations struggle to make themselves heard. I am aware of a sense of expectation. A sonorous voice makes an announcement, none of which makes sense to me. My mother sinks into a chair and my father puts his hand on her shoulder in a rare moment of empathy. We are at war with Germany. I have no idea what this means. I amnot at all sure if I know what Germany is. I know thst, in his younger days, my father had been a soldier, I had seen pictures of him in uniform. To me my father was unimaginably old, far too old to become a soldier again. What seemed to be upsetting my mother was the fact that my brother, some twelve years older than I am, was certain to be called up.

Life goes on as normal. I attend the local Infants' School. The walk to school is short and apart from the occasional bus, a very few cars and lorries and one or two horse drawn carts, the walk is traffic free.

The war does not seem to materialise, in spite of the shelters that are being built and the appearance of Air Raid Wardens, one of which is my eldest sister. I move to the junior school. This is another ten minutes walk away. Part of the school adjoining the playground has been partitioned off. We can still see through the windows and much speculation develops about the sides of meat that we can see hanging there. Later, I was to learn that this was an emergency supply in case of invasion.

Life goes on much as usual. It is noticeable that there are fewer men around and even less traffic. One of our sceret excitements on the way to school is to peer through a hole in a fence to see a car without wheels, propped up on bricks for the duration of the war. Blackout cutains are installed and the glass is criss-crossed with strips of brown paper tape in order to prevent the glass from splintering under the effects of bomb blast. It is a peaceful time, with little noise as there is almost no traffic around, even in a suburb of London.

At last come the air raids. We live near to a railway marshalling yard, a tempting target for the bombers. For a small child there is no sense of danger, no fear of being killed. The prospect is just not understood at that age. What is terrifying is the noise. The wail of the air raid sirens, followed by the drone of aircraft and, worst of all, the crash of the anti-aircraft guns. The explosion of bombs is a much less worrying noise. Soon, we have a new craze. This is collecting shrapnel. As the anti-aircraft shells explode in the sky they spray out pieces of the shell casing, known as shrapnel. These lethal pieces rain down on streets and houses. There must have been more danger from shrapnel than from German bombs. Most shrapnel is just jagged pieces of metal, but sometimes is found a section, perhaps from a fuse setter, that has numbers and a scale engraved upon it. These are much sought after and are the focus of much envy among collectors. There are even unexploded incendiary bombs found in such collections. One such device stood on our mantelpiece until my father was persuaded of its dangers and took it to the police station. They, of course, refused to accept it and it was left in the station yard in a bucket of sand.

Eventually I was evacuated to my grandparents' cottage in Cambridgeshire. I have vivid memories of my time there. The cottage was primitive; thatched roof, whitewashed walls,an outside chemical toilet, a well for water and cookin upon a paraffin stove. The only lighting was from oil lamps. For a young child, in effect on his own, this was bad enough. The cottage,at night, is full of dark corners and strange shadows cast by the flickering lamps. To add to this there is the proximity of several airfields on the flat Cambridgeshire countryside. To a child already fearful of the noise of raiding aircraft the constant roar of aircraft landing or taking off is sheer torture.

I go to the village school. This has two classrooms, one for the older children and one for the younger. The village children are far from friendly to an incomer and take every opportunity to make our lives a misery. Eventually my mother decides that I shall return home, bombing or not.

The Battle of Britain

I return home to a different world. Workmen arrived and dug a pit in our garden to erect an Anderson Shelter. This is a hole in the ground, walled and floored with concrete, with a roof of corrugated iron. The soil excavated from the hole is used to cover the iron and give it some extra protection. The shelter is used a few times, but it is damp, in fact it fills with water in the wet weather and so its use was very limited. In the daylight raids I am sent to the shelter, while my mother continues with her housework. I sit in the entrance to the shelter and watch the condensation trails of the British and German aircraft as they battle overhead.

By now my father has joined the Home Guard or Local Defence Volunteers, as they were then known. He eventually brings home a Lee Enfield rifle and a clip of five bullets. I am allowed to clean the rifle by tugging on the pull-through with its piece of oily rag on the end. The only time when the rifle is near to being used is when a German aircraft flies low up and down our street. It eventually drops a bomb on the local railway station and machine guns the area. My father wants to go to an upstairs window and shoot back, but my mother vetoes the idea.

The Blitz

The air raids that we have known now pale into insignificance against what we now experience. Night after night the sirens wail. A period of quiet and then we hear the sound of anti-aircraft guns getting nearer and nearer as the bombers approach. As the planes fly nearer there is the distinctive growl of unsynchronised engines; a steady two tone beat that, even for a young boy, sends shivers of apprehension through the body. We do not go to the public shelter. My mother has the idea that these are unclean and full of bugs. Soon, the bombs start to fall. At this time they are only small bombs and the blast effect is fairly local. The house opposite is hit, but we only sustain cracked windows.

One evening the bombing is so intense that we decide to go to the public shelter. As we make our way up the blacked out road we stumble over rubble and realise that the house a few doors away has been hit. There is a single Air Raid Warden digging in the rubble, the only aid available. We reach the shelter in a rain of shrapnel only to be turned away, it is full.

And so to school the next day. I cannot remember any of my classmates being bombed out although this must have occured. The intensity of what is happening tends to make a barrier grow up around you, so that you shut ot the world that is causing you distress. When the siren sounds we are led off to the shelter, where we are given maths books to work through. Whenw e reach the end we start again. It is an efficient means of creating a dislike of a subject.

School and family life go on as normally as possible. Rationing has taken hold and food becomes scarce. We children find a new game. We use the hollowed out stems of large weeds as pea shooters. There are no peas but one boy finds that pearl barley can be bought. This is ideal ammunition and we are soon in full battle in the play ground. Our game is short lived. One of the teachers discovers what we are doing and reports to the Head Teacher. The result- a public condemnation and a lecture on wasting food in war time.

The Home Guard is becoming more visible. My father goes off to parades in full uniform with his rifle. They hold exercises in the street that attract crowds of interested children as onlookers. My father goes off to guard the local gas works agianst Fith Columnists. These are Nazi sympathisers who are waiting to create havoc when the invasion comes.

Christmas comes round again and my father manges to find a chicken from one of his cutomers. Presents are few, but a lull in the bombing makes up for the deficiency. Or so my elders and betters tell me.

1941

By now we have fallen into a routine. Air raids are accepted as a normal part of life. We are told to 'Dig for Victory'. In other words grow vegetables in your garden. My father buys a pair of rabbits to breed for extra meat. I am sent with one of the does to a neighbour in order to mate the doe with his buck. I suspect that this was as far as my parents were prepared to go with sex education! We also bought some day old chicks, but they failed to survive, probably because we could not obtain the correct food.

!942-44

Tis was a period where nothing seemed to change.As small children we were shielded from the horrors of war as much as possible. On one occasion the Home Guard gave a party for the local children This was held in a church hall. The entertainers were a group dressed as cowboys, singing cowboy songs. During their performance we were dimly aware of explosions outside, but the performers just sung louder. Afterwards, we found that there had been a major air arid on the ditrict, but we children knew nothing of it.

The Home Guard keeps my father busy. They are called out to search for anti-personnel bombs that have been dropped. these are small bombs that, on landing, extend wings. If these are disturbed the bomb explodes. The main concern is that we children might find them.

The Americans arrive. My father instructs me to give up my seat on the bus to an American soldier. He, in return, gives me a packet of chewing gum. I have no idea what it is.

And then come the VIs or doodlebugs. These fly in wih a throaty roar like a badly tuned motor bike. When they tip up to start their final dive the engine cuts out. When this happens we dive for the Morrison shelter in our living room. This shelter is nothing more than a table made from steel. It does give protection if the house collapses in a a raid. All the family, five of us now that my brother is in the army, sleep within its protection. It is not someting that I would recommend.

1945

I go to grammar school in Islington. This means a thre quarters of an hour bus journey. I am not yet eleven and travelling by myself, with the possibilty of a V1 attack at any time. How attitudes have changed! Soon the V2 rockets are falling on London. There is no warning, the explosion is the first and last warning. Waiting for the bus home one day, one falls nearby and the chimney pots come tumbling. Fortunately the intervening buildings shield the blast.

As the invasion of Europe approaches we see waves of Lancaster bombers fly over London, I suspect to raise moral. We have a wall map at home with flags to show the position of allied troops. When the advance over runs the launching sites we have a welcome return to peaceful days.

1945

When 1945 arrives we realise that the war is almost over. There are bomb sites everywhere and people are shabby and tired. Finally the Geramns surrender and VE Day is celebrated. I am taken to central London to see the celebrations but am overwhelmed by the crowds. For us this is the end of the war. VJ day has yet to come , but the Japanese are on the other side of the world. Afterwards we wil suffer austerity in an impoverished country. But that is to come.

Contributed originally by richard_storer (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Boy's Wartime Memories of London and Dorset

Richard Storer

London

I was born in Hampstead, London in 1933 and though I was too young to understand the concerns and worries that my parents and other adults in the family must have had during the period leading up to the declaration of war, some of it must have been absorbed by my imagination as I have clear memories of digging a large hole which was to be an air raid shelter in our back garden. I don't suppose I had any idea of what an air raid shelter was for but it must have been clear to me that it was something that was going to be needed and that digging a hole was the initial requirement. I also remember that I was careful to dig my hole with a shelf cut into the soil on one of the sides so that I would have somewhere to put a bottle of Heinz tomato ketchup. Presumably I must have overheard talk of stocking shelters with supplies of food and tomato ketchup was obviously something that I did not want to be without.

Amongst my other memories from those times leading up to the war are those of Walls ice cream men pedaling their tricycles round the streets ringing their bells and, when stopped, handing over water ices which were contained in a cardboard tube of triangular cross section. You had to push the ice up from the bottom of the tube and I can still taste the soggy cardboard that used to end up surrounding the business end of the ice. I also remember coal being delivered to London houses by horse and cart, being taken to have afternoon tea at Selfridges and the wonderful model train layout that ran all round the first floor in Hamleys' Regent Street toy shop.

Dorset

An aunt of mine had a house in the village of Chideock in Dorset and I was sent out of London to live with her just before the war started. I was not really aware of why I had been sent to out of London as the move was just like the other Dorset holiday visits to my aunt that had gone before. The reality of what was happening in the world was made a bit clearer when Hobbs, who looked after my aunt's garden, told me on the afternoon of 3rd September 1939 that we were at war with Germany. Hobbs must have been dismayed at what was happening in Europe as he had been lucky to survive the whole of the First World War spent in the trenches of France and Flanders. Many others who served in the same trenches never came home to their Dorset village homes.

To begin with, nothing seemed to alter in West Dorset. We still went down to the beach. The beach huts remained in use and the cafe still dispensed trays with pots of tea for the grown ups and ice cream for the children. Slowly, however, things started to change. I remember one day when we were on the beach that a camouflaged aeroplane, friend or foe I know not, came hurtling in from the sea just feet above the wave tops and lifted up to pass over our heads and disappeared inland along the deep valley that led to the village. Eventually the cafe was taken over by the Home Guard and the cart track that we used for walking to the beach was rebuilt in concrete so that a continuous stream of lorries could wend their way to the shore to be loaded up with pebbles and then return inland with their cargo along the other tarmac road to make even more concrete to be used in the war effort. That concrete track still exists and, though a bit cracked here and there, is still serviceable and in daily use. Sitting on the beach we would sometimes see depth charges or other explosives erupting in the water further out to sea in the Channel. One evening we watched a dog fight by some aeroplanes in the sky just off the coast, eventually seeing one come down, trailing smoke as it dived seawards and followed by a lone parachutist who landed in the sea off Lyme Regis. We subsequently learned that he was a German.

At the beach, the mouth of the valley between the cliffs was eventually filled with a huge wall of scaffolding and the beach itself was dotted with concrete cube obstacles about five feet square and with sloping tops. The bits of low cliff that did not pose a major obstacle to an invading army were wired off and laid with mines. Post holes were dug in the roads leading from the beach and also along the main coast road that ran East West through the village. These holes had removable caps and, at the side of the road, were stored lots of substantial, iron, antitank constructions which would be slotted into the uncapped holes once an invasion seemed imminent. I also remember, and looking back I cannot believe how naive we must have been, that my cousins and I ventured down to the beach and set up watch on the night of the full moon that had been identified by the press as the likeliest time for Hitler to try and invade England. Thank heavens he never came.

Though I remember having been given a gas mask I never remember having to carry it with me in one of the square, brown, cardboard boxes suspended by a bit of string over the shoulder that one sees so often in archive film of the period. I do however remember that another aunt of mine living in London had a shelter bearing some government minister's name ( not Anderson ) which stood in the middle of her front hall and resembled a large rectangular dining room table made out of solid metal of some kind. The idea was that anybody sheltering underneath it would be protected from collapsing walls and other falling rubble should the house be bombed. This aunt's shelter was always draped with a large table cloth and usually sported a pot plant or a vase of flowers placed carefully in the centre. This shelter was never called into service but, towards the end of the war, a V2 rocket did land two houses away down the street and the family portrait of "Uncle Sam" (circa 1820) was damaged by flying debris. My grandmother never forgave " that dreadful Mr Hitler" for the outrage.

I was a wolf cub whilst living in Dorset and I remember on a couple of occasions being put on an open lorry with Arkela and the rest of the cub pack to take part in processions through the local town of Bridport during Spitfire Week or Salvage Week or some other week designed to help the war effort. All sorts of metal was collected at this time; aluminium cooking pots to make aeroplanes and all the iron railings were removed from the tops of the low brick or stone walls which had commonly fronted many houses before the war started.

When rationing was introduced my aunt adopted what, in retrospect, I now realise was a very sensible routine with the rations for the household. She put to one side all the butter, sugar and jam that she required for the week's cooking and, from what was left over, everybody was then issued with their own personal tea time rations for the week. The top of the tea trolley became covered in pots, jars and other containers each containing the jam, sugar and butter belonging to the child whose name appeared on the container label. We were at liberty to eat the lot at Monday tea time if we wished but we would not be issued with any more until the next week's rations were distributed. It was a learning exercise which taught us many disciplines: self control, fair shares, planning, frugality, contributing to the common good etcetera. Like many families during the war, we augmented the shop bought rations by keeping chickens, ducks and rabbits and by growing lots of vegetables.

I remember soldiers being billeted in the village. We had a couple of Highlanders with us in my aunt's house and a piper used to play through the village in the mornings presumably to collect the scattered Scotsmen all together before they went off to their daily duties. I also remember Royal Welch Fusiliers with the black flaps sewn to the collars on the back of their khaki battle dress; flaps which the regiment had worn for hundreds of years ever since a previous Colonel had decided that his soldier's tunics needed to be protected from the white powder on the pigtails of their wigs. At a time when the country faced the ultimate challenge for survival, only the British could go to war in the twentieth century believing that it was still important to protect their battle dress from wig powder. Long may such traditions endure. The only 'action' that came anywhere near us in our Dorset village was one night when a German bomber, presumably fed up and wanting to go home, just jettisoned his bombs which landed harmlessly on the hillside on the outskirts of the village but provided a topic of conversation for several weeks afterwards.

In 1942 I left my aunt's home in Dorset moved to Suffolk to join my mother and stepfather.

After the war ended in 1945 I went back to look at the home where I had been born in 1933. The house where we had a flat was still there but a nunnery that was 2 door away had been bombed and apparently some of the resident nuns were killed. I also went down the road and round the corner to take a look at the nursery school that I used to be taken to in the mornings. As I walked towards it, memories of the smell of Jey's Fluid which was liberally used in the toilet came back to me and I wondered if the smell would still be there. The smell had gone and so had the nursery school, bombed like so much else in London.