Incendiary Bomb at Denmark Hill

Description

Incendiary Bomb :

Source: 24 hours of Blitz Sept 7th 1940

Fell on Sept. 7, 1940, at 9:10 p.m.

Present-day address

Denmark Hill, Camberwell, London Borough of Southwark, SE5 8RS, London

Further details

Maudsley Hospital, Denmark Hill, Southwark, London SE5 8AZ, London, UK ; IB in grounds

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

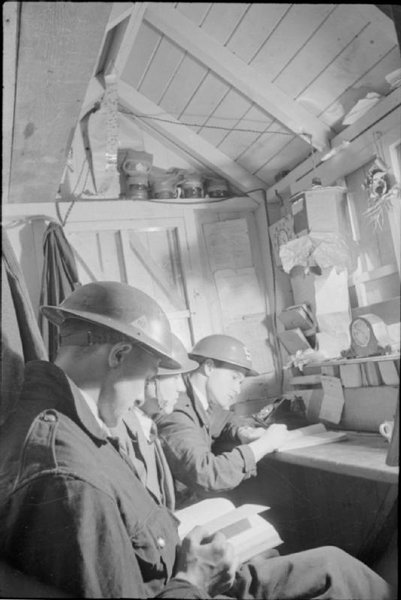

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Sporadic air-raids went on all through 1943, but as Autumn came, bringing the dark evenings with it, the "Little Blitz" started, with plenty of bombs falling in our area and I got my first real experience of NFS work.

There were Air-Raids every night, though never on the scale of 1940/41.

By now, my own School, St. Olave's, had re-opened at Tower Bridge with a skeleton staff of Masters, as about a hundred boys had returned to London.

I was glad to go back to my own school, and I no longer had to cycle all the way to Lewisham every day.

Part of the School Buildings had been taken over by the NFS as a Sub-Station for 37 Fire Area, the one next to ours, so luckily none of the Firemen knew me, and I kept quiet about my evening activities in School. I didn't think the Head would be too pleased if he found out I was an NFS Messenger.

The Air-Raids usually started in the early evening, and were mostly over by midnight.

We had a few nasty incidents in the area, but most of them were just outside our patch. If we were around though, even off-duty. Sid and I would help the Rescue Men if we could, usually forming part of the chain passing baskets of rubble down from the highly skilled diggers doing the rescue, and sometimes helping to get the walking wounded out. They were always in a state of shock, and needed comforting until the Ambulances came.

One particular incident that I can never forget makes me smile to myself and then want to cry.

One night, Sid and I were riding home from the Station. It was quiet, but the Alert was still on, as the All-Clear hadn't sounded yet.

As we neared home, Searchlights criss-crossed in the sky, there was the sound of AA-Guns and Plane engines. Then came a flash and the sound of a large explosion ahead of us towards the river, followed by the sound of receding gunfire and airplane engines. It was probably a solitary plane jettisoning it's bombs and running for home.

We instinctively rode towards the cloud of smoke visible in the moonlight in front of us.

When we got to Jamaica Road, the main road running parallel with the river, we turned towards the part known as Dockhead, on a sharp bend of the main road, just off which Dockhead Fire-Station was located.

Arrived there, we must have been among the first on the scene. There was a big hole in the road cutting off the Tram-Lines, and a loud rushing noise like an Express-Train was coming from it. The Fire-Station a few hundred yards away looked deserted. All the Appliances must have been out on call.

As we approached the crater, I realised that the sound we heard was running water, and when we joined the couple of ARP Men looking down into it, I was amazed to see by the light from the Warden's Lantern, a huge broken water-main with water pouring from it and cascading down through shattered brickwork into a sewer below.

Then we heard a shout: "Help! over here!"

On the far side of the road, right on the bend away from the river, stood an RC Convent. It was a large solid building, with very small windows facing the road, and a statue of Our Lady in a niche on the wall. It didn't look as though it had suffered very much on the outside, but the other side of the road was a different story.

The blast had gone that way, and the buildings on the main road were badly damaged.

A little to the left of the crater as we faced it was Mill Street, lined with Warehouses and Spice Mills, it led down to the River. Facing us was a terrace of small cottages at a right angle to the main road, approached by a paved walk-way. These had taken the full force of the blast, and were almost demolished. This was where the call for help had come from.

We dashed over to find a Warden by the remains of the first cottage.

"Listen!" He said. After a short silence we heard a faint sob come from the debris. Luckily for the person underneath, the blast had pushed the bulk of the wreckage away from her, and she wasn't buried very deeply.

We got to work to free her, moving the debris by hand, piece by piece, as we'd learnt that was the best way. A ceiling joist and some broken floorboards lying across her upper parts had saved her life by getting wedged and supporting the debris above.

When we'd uncovered most of her, we used a large lump of timber as a lever and held the joist up while the Warden gently eased her out.

I looked down on a young woman around eighteen or so. She was wearing a check skirt that was up over her body, showing all her legs. She was covered in dust but definitely alive. Her eyes opened, and she sat up suddenly. A look of consternation crossed her face as she saw three grimy chaps in Tin-Hats looking down on her, and she hurriedly pulled her skirt down over her knees.

I was still holding the timber, and couldn't help smiling at the Girl's first instinct being modesty. I felt embarassed, but was pleased that she seemed alright, although she was obviously in shock.

At that moment we heard the noise of activity behind us as the Rescue Squad and Ambulances arrived.

A couple of Ambulance Girls came up with a Stretcher and Blankets.

They took charge of the Young Lady while we followed the Warden and Rescue Squad to the next Cottage.

The Warden seemed to know who lived in the house, and directed the Rescue Men, who quickly got to work. We mucked in and helped, but I must confess, I wish I hadn't, for there we saw our most sickening sight of the War.

I'd already seen many dead and injured people in the Blitz, and was to see more when the Doodle-Bugs and V2 Rockets started, but nothing like this.

The Rescue Men located someone buried in the wreckage of the House. We formed our chain of baskets, and the debris round them was soon cleared.

To my horror, we'd uncovered a Woman face down over a large bowl There was a tiny Baby in the muddy water, who she must have been bathing. Both of them were dead.

We all went silent. The Rescue Men were hardened to these sights, and carried on to the next job once the Ambulance Girls came, but Sid and I made our excuses and left, I felt sick at heart, and I think Sid felt the same. We hardly said a word to each other all the way home.

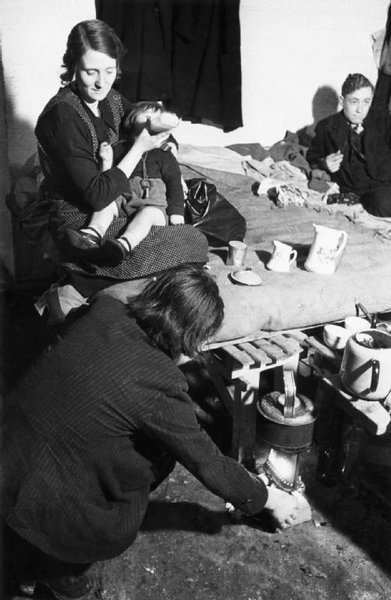

I suppose that the people in those houses had thought the raid was over and left their shelter, although by now many just ignored the sirens and got on with their business, fatalistically taking a chance.

The Grand Surrey Canal ran through our district to join the Thames at Surrey Docks Basin, and the NFS had commandeered the house behind a Shop on Canal Bridge, Old Kent Road, as a Sub-Station.

We had a Fire-Barge moored on the Canal outside with four Trailer-Pumps on board.

The Barge was the powered one of a pair of "Monkey Boats" that once used to ply the Canals, carrying Goods. It had a big Thornycroft Marine-Engine.

I used to do a duty there now and again, and got to know Bob, the Leading-Fireman who was in-charge, quite well. His other job was at Barclays Brewery in Southwark.

He allowed me to go there on Sunday mornings when the Crew exercised with the Barge on the Canal.

It was certainly something different from tearing along the road on a Fire-Engine.

One day, I reported there for duty, and found that the Navy had requisitioned the engine from the Barge. I thought they must have been getting desperate, but with hindsight, I expect it was needed in the preparations for D-Day.

Apparently, the orders were that the Crew would tow the Barge along the Tow-path by hand when called out, but Bob, who was ex-Navy, had an idea.

He mounted a Swivel Hose-Nozzle on the Stern of the Barge, and one on the Bow, connecting them to one of the Pumps in the Hold. When the water was turned on at either Nozzle, a powerful jet of water was directed behind the Barge, driving it forward or backward as necessary, and Bob could steer it by using the Swivel.

This worked very well, and the Crew never had to tow the Barge by hand. It must have been the first ever Jet-Propelled Fire-Boat

We had plenty to do for a time in the "Little Blitz". The Germans dropped lots of Containers loaded with Incediary Bombs. These were known as "Molotov Breadbaskets," don't ask me why!

Each one held hundreds of Incendiaries. They were supposed to open and scatter them while dropping, but they didn't always open properly, so the bombs came down in a small area, many still in the Container, and didn't go off.

A lot of them that hit the ground properly didn't go off either, as they were sabotaged by Hitler's Slave-Labourers in the Bomb Factories at risk of death or worse to themselves if caught. Some of the detonators were wedged in off-centre, or otherwise wrongly assembled.

The little white-metal bombs were filled with magnesium powder, they were cone-shaped at the top to take a push-on fin, and had a heavy steel screw-in cap at the bottom containing the detonator, These Magnesium Bombs were wicked little things and burned with a very hot flame. I often came across a circular hole in a Pavement-Stone where one had landed upright, burnt it's way right through the stone and fizzled out in the clay underneath.

To make life a bit more hazardous for the Civil Defence Workers, Jerry had started mixing explosive Anti-Personnel Incendiaries amonst the others. Designed to catch the unwary Fire-Fighter who got too close, they could kill or maim. But were easily recogniseable in their un-detonated state, as they were slightly longer and had an extra band painted yellow.

One of these "Molotov Breadbaskets" came down in the Playground of the Paragon School, off New Kent Road, one evening. It had failed to open properly and was half-full of unexploded Incendiaries.

This School was one of our Sub-Stations, so any small fires round about were quickly dealt with.

While we were up there, Sid and I were hoping to have a look inside the Container, and perhaps get a souvenir or two, but UXB's were the responsibility of the Police, and they wouldn't let us get too near for fear of explosion, so we didn't get much of a look before the Bomb-Disposal People came and took it away.

One other macabre, but slightly humorous incident is worthy of mention.

A large Bomb had fallen close by the Borough Tube Station Booking Hall when it was busy, and there were many casualties. The lifts had crashed to the bottom so the Rescue Men had a nasty job.

On the opposite corner, stood the premises of a large Engineering Company, famous for making screws, and next door, a large Warehouse.

The roof and upper floors of this building had collapsed, but the walls were still standing.

A WVS Mobile Canteen was parked nearby, and we were enjoying a cup of tea with the Rescue Men, who'd stopped for a break, when a Steel-Helmeted Special PC came hurrying up to the Squad-Leader.

"There's bodies under the rubble in there!"

He cried, his face aghast. as he pointed to the warehouse "Hasn't anyone checked it yet?"

The Rescue Man's face broke into a broad smile.

"Keep your hair on!" He said. "There's no people in there, they all went home long before the bombs dropped. There's plenty of dead meat though, what you saw in the rubble were sides of bacon, they were all hanging from hooks in the ceiling. It's a Bacon Warehouse."

The poor old Special didn't know where to put his face. Still, he may have been a stranger to the district, and it was dark and dusty in there.

The "Little Blitz petered out in the Spring of 1944, and Raids became sporadic again.

With rumours of Hitler's Secret-Weapons around, we all awaited the next and final phase of our War, which was to begin in June, a week after D-Day, with the first of them to reach London and fall on Bethnal Green. The germans called it the V1, it was a jet-propelled pilotless flying-Bomb armed with 850kg of high-explosive, nicknamed the "Doodle-Bug".

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by Berylsdad (BBC WW2 People's War)

BRAVERY

In those early days of the Blitz, there were many unsung heroes who, by their personal conduct and fervent belief that we could beat the menace of Hitler’s frightfulness, inspired us to carry on and keep London working. So little has been recorded of how this threat to our great city was successfully combated by the ordinary man in the street. As a nation, we are chary of patting ourselves on the back and it is, perhaps, for that reason, that the bravery of so many has been recognised by so few.

Amongst the unsung heroes, there will always remain in my memory a comrade by the name of Edward Bennett of Lyndhurst Way, Camberwell, affectionately known to members of the Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot as “Pop”. It was this oft-blitzed depot that the late Vivian Woodward served and Ted Heming learned first-aid and rescue work that was later to help him to win his George Cross. Cambridge University students also did relief work there and, as a tribute to the staff, afterwards entertained our Depot’s cricket team at Cambridge, where Vivian probably played his last cricket match and Ted was included in the team.

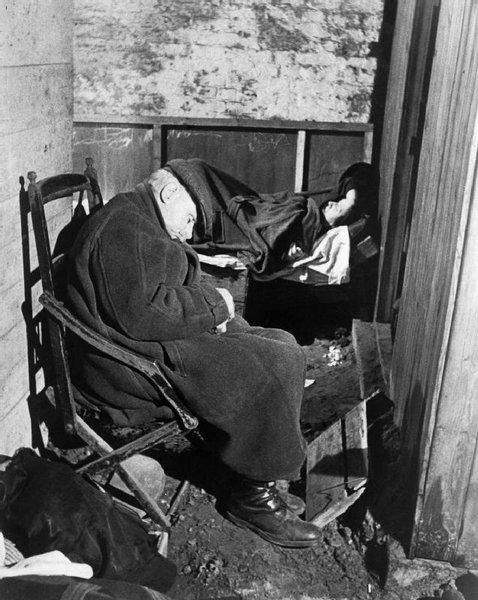

Our “Pop” was nearly sixty years of age when he joined the Civil Defence, his duties covering the period of 24 hours on and 24 hours off. But when the Blitz on London started, Pop, like many others, voluntarily became ‘on-call’ on his off-duty nights and therefore available to fill any gap that might occur in the on-duty ranks. This often meant continual work over thirty-six hour periods. During those hectic days and nights, Pop, if not require for any other duty, would take up position in an ordinary unprotected Sentry Box, situated just outside the Depot, and keep fire-watch whilst indulging in a humorous commentary upon the way “Jerry” was “getting it” in the battle raging overhead. Despite many requests from his friends to take advantage of cover, Pop would still carry on. There is no doubt that his humour and sangfroid did much to raise the morale of his team-mates in those early days. One night, when Pop was out at an incident, the Sentry Box was blown to smithereens by a bomb exploding just outside the Depot. But, box or no box, Pop still continued, in his spare moments, to stand in the same position and his lively commentaries remained unabated. His devotion to duty was tremendous and it is due to this fact that we lost an untiring and heroic figure. The responsibility for his passing lies primarily with the dropping of a large enemy bomb, but the chemical deposits in Mother Earth subscribed in a mysterious way to our loss.

On 4th October, 1940, when Pop was officially off-duty, he reported as usual as being available ‘on-call’. After a quiet beginning to that fateful night, Camberwell soon received its usual strafing. Amongst the quota was a heavy HE bomb that dropped in a garden close to our Depot. The action of the bomb was weird in effect, for although it penetrates the earth very deeply, throwing tons of clay into the adjoining streets, and the explosion severely blasted surrounding houses, there was little sign of a crater, the point of impact only being marked by a ring of fire on the surface of the ground that afterwards was recognised by the experts as due to the ignition of subterranean gases. Some minutes elapsed before Headquarters assigned one of our Parties to cover the incident, but Pop, not bound by the necessity of awaiting an official order, had dashed round to the spot to see if his first-aid qualifications were needed. Happily, except for a few slight shock cases, no-one was injured, but a number of women in nearby Anderson shelters were pleading for the flames, that were now reaching considerable proportions, to be extinguished. At that stage of the Blitz, most people, influenced no doubt by the Official Lighting Order, regarded ground lights of any nature as a greater menace to safety than any danger that existed in the battle raging overhead. The first-aid Party sent from our Depot arrived on the scene to find Pop endeavouring to smother the flames with earth. As they approached, they almost immediately felt themselves being drawn as if by magnetic forces towards the spot from which Pop was operating. Flinging themselves to the ground, they just managed to evade being sucked into the centre of the flames. When they picked themselves up some moments later, the fire had partly subsided, but Pop and a valiant helper had vanished, without a cry or any indication of distress, into the bowels of the earth. Despite frenzied digging by his comrades that night and subsequent weeks of endless toil by specialised rescue teams, not a single particle of clothing or equipment or clue to their whereabouts was then or since discovered. The official theory was that Pop and his friend were drawn by suction down to a subterranean stream for, although powerful pumps were employed, water at 20 feet made further excavation work impossible.

But, though Pop vanished beyond our ken, he will ever remain in the hearts of all who served at Bellenden Road, as a very gallant and unsung hero.

C R Mercer

Superintendent, Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot

Contributed originally by jogamble (BBC WW2 People's War)

My Grandfather was Flight Lieutenant Leonard Thomas Mersh and this is just a glimpse in his life during World War 2, like many of the pilots he has a number of log books, with many miles accounted for and the stories to go with them.

Len went to Woods Road School in Peckham and then on to Brixton School of Building, where he qualified as a joiner. In 1938 at 18 he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. At Aberystwyth he made the grade to be a pilot and was then sent to Canada for further training in Montreal and Nova Scotia Newfoundland where he gained his wings on Havards and Ansons.

Once back in England he went to Aston Downs and flew many aircraft across England, eventually he was posted to East Kirby in Norfolk attached to 57 Squadron Bomber Command. He flew many missions over Germany and France and as far as the Baltic. Missions included laying mines in the fjords where submarines and battleships where hidden. Dresden; Droitwich, Hamberg, Nuremberg, Brunswick and Gravenhorst were some of the places he bombed. Some times he carried the Grand Slam bomb.

In January 1945 he and his crew where sent to Stettin Harbour to lay mines at night. They where one of the lucky ones, as 350 planes had been sent and only 50 came back. Granddad’s plane was attacked by enemy fighters and was hit but they managed a second run over the target to release their mines.

In March 1945 during a sortie against Bohlen, his aircraft was attacked by a Junkers 88. The plane was hit but they made three bombing runs and then hedgehopped back to England.

On the 26th October 1945 Leonard was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, (DFS), for courage, determination and efficiency.

After completing operational tours and six mine laying sorties he was drafted to 31 Squadron, Transport Command at the end of the Dutch Indonesian Campaign flying VIPs. He flew General Mansergh to Bali being the first RAF plane to land on March 8th 1945 to accept the Japanese surrender.

In 1948 Leonard was drafted to Germany to help with the Berlin Airlift. The squadron reopened airstrips which had been closed at the end of the war, plot routes into Berlin and get them working, the Americans would move in and the squadron would move on to another station. They flew by day and night and were lucky to gain 5hours sleep, which was taken in Mess chairs, which is perhaps why he caught TB, which ended his career and he then spent a lot of time in and out of hospital.

Contributed originally by Enabea (BBC WW2 People's War)

Kallender Marjorie

I lived in London during the war. I was an air raid warden in South London. I worked in Victoria and walked to the warden post in the black out wearing a tin hat and carrying a gas mask it four miles. I never actually used my gas mask, and we had the tests in a Nissan hut, firstly with the gas mask, then without which was horrible, although very quick, as we ran through. We had to do it quietly, because if they heard you running they made you go back and do it again slowly!

I met my husband at the Peckham health center and social club about 1938. We married in the ruins of the church, St Judes in Peckham, on a foggy cold morning he had to report to his regiment. We married at 10am and his train left at 2pm. Sad. It was a long parting. He was posted to Egypt for four years.

I worked as a hairdresser with Arnott & Rosse in Victoria until I retired at sixty to look after my husband who had cancer. He had his last wish and died at home in our living room it was very sad. He was at the Cromwell first as an outpatient, the specialist sent me out to get a sandwich and when I got back he told me he had two years to live. In fact, he lived about two and a half years after that.

I lived in Central London I was bombed out of three homes. My mother managed to get house in Peckham 4 Whittington Road where my husband and I lived until we bought a house in Pimlico.

Fred and I had to leave our very nice house, after he modernized it and redecorated it, as the local council compulsorily purchased all the land and gave us two hundred pounds. They built a block of flats on the land which are still there today.

We put the money towards 90 Warwick Way, which had been owned by an elderly lady who died — it was in a poor state of repair, and we had to borrow money and do a lot of repairs. We made it into two self-contained flats, which we let out firstly to an accountant. Then he was recalled to Birmingham and we found another tenant, a woman from Australia.

We had my mother in the flat with us — it wasn’t so easy, I was still working as a hairdresser at 49 Warwick Way, Arnott and Rosse, run by two ladies, who I helped to look after when they became ill, as well as their mother. One hemorrhaged and I took her to hospital, which is now a big hotel at Hyde Park Corner. The other lady was trying to clear a drain with caustic soda, got it all over her hands; I got the doctor for her. I told Mrs Rosse’s daughter, Esther Macdonald, who was married to a doctor and lived in Surrey, and all she did was turn up, take the ration books for her mother and her aunt, drew the rations and downstairs they had some very old furniture, Jacobean, and she took it out and sold it. When those two ladies died, they left a will, which I was to be included in, for a certain amount of money. Esther disputed it so my husband and I got a solicitor and we got a small sum of money. She wanted me to run the shop which I did, she used to come take money out of the till, leave an I.O.U.

During air raids, our shop windows were blown out, the shop across the road got a firebomb and the two corner shops, one a hat shop the other a butchers, were completely destroyed, leaving just a hole. We used to ask the customers if they wanted to leave during an air raid, but mostly they would say to continue so we worked throughout air raids. The shop closed at seven and I had to walk to Peckham to become an air raid warden, four miles, which took me three hours. You reported to the post, and if they said you weren’t needed you could go home and they would come and get us if necessary. This didn’t often happen! The wardens were responsible for the number of people in the houses and we had to find out if they were in the houses or in the garden shelters at the back and often they were in the pubs!

My husband Fred was in Caterick first in 1939 and then he was sent to Egypt in 1940, where he was in some caves in the desert. The caves were originally used to extract stones for the pyramids. He came home in 1945, and he was sent to Hampshire. And he was there until he was discharged a year later and worked for North Thames Gas as a communications officer. He never spoke about his time in the army. He only remembered the worst bits and he wouldn’t tell me about those.

I only got two letters from him during this time — they didn’t get through. Maybe they got put on a ship or a plane? I used to send him parcels with brushes and polish, toothpaste and socks, which is what he wanted as the army didn’t supply them. And through the bank sent him a draft as his watch got stolen. He got most of my letters, even though they took a long while.

Until my husband came home, my mother had the ration books and she’d collect the rations until we moved to Victoria and she’d go to the butchers in Warwick way — the maypole.

My mother subsequently became very ill with cancer and she was taken to the Old Westminster Hospital. I used to rush and visit her and she died there after a year.

I’m originally from great Yarmouth in Norfolk and that’s where I had my first air raid when I was eighteen. I moved to London with my family because the house was bombed and we lived first for eighteen months in Asylum Road, until we got bombed there, then we moved to Clifton crescent, again in Peckham, for less than a year until once more we were bombed out, so we went to Whittington road which my mother found.

As I’d been left half the hairdressers, we bought the other half from Esther, modernized it and ran it until I was sixty. My husband made me retire then, and dragged me off to the social services as I hadn’t realized I could get a pension. So now I go to the Post Office every week and draw my pension.

On VE Day a lot of the streets had street parties.

These are some of the things I experienced in my apprenticeship we had a metal container over gas ring which was filled with green soap

which was our shampoo the water to the basins came from a large metal tank which was heated with two large open gas rings. One lunch time I was invited to a friend’s house, when I retuned water was pouring out of the door. The water tank had burst. My husband helped Miss Arnott to obtain and install small electric water heaters by each baisin which were a great improvement.

On the ground floor were wooden cubicles painted green and orange. The shop windows had glass sliding panels which I had to clean. The cubicle curtains which had to drawn so no one person could the other ito shampoo thnen be watch and hand things to the first asstiant

Kallender Marjorie

I lived in London during the war. I was an air warden in South London. I worked in Victoria and walked to the warden post in the black out wearing a tin hat and carrying a gas mask it four miles. I never actually used my gas mask, and we had the tests in a Nissan hut, firstly with the gas mask, then without which was horrible, although very quick, as we ran through. We had to do it quietly, because if they heard you running they made you go back and do it again slowly!

I met my husband at the Peckham health center and social club about 1938. We married in the ruins of the church, St Judes in Peckham, on a foggy cold morning he had to report to his regiment. We married at 10am and his train left at 2pm. Sad. It was a long parting. He was posted to Egypt for four years.

I worked as a hairdresser with Arnott & Rosse in Victoria until I retired at sixty to look after my husband who had cancer. He had his last wish and died at home in our living room it was very sad. He was at the Cromwell first as an outpatient, the specialist sent me out to get a sandwich and when I got back he told me he had two years to live. In fact, he lived about two and a half years after that.

I lived in Central London I was bombed out of three homes. My mother managed to get house in Peckham 4 Whittington Road where my husband and I lived until we bought a house in Pimlico.

Fred and I had to leave our very nice house, after he modernized it and redecorated it, as the local council compulsorily purchased all the land and gave us two hundred pounds. They built a block of flats on the land which are still there today.

We put the money towards 90 Warwick Way, which had been owned by an elderly lady who died — it was in a poor state of repair, and we had to borrow money and do a lot of repairs. We made it into two self-contained flats, which we let out firstly to an accountant. Then he was recalled to Birmingham and we found another tenant, a woman from Australia.

We had my mother in the flat with us — it wasn’t so easy, I was still working as a hairdresser at 49 Warwick Way, Arnott and Rosse, run by two ladies, who I helped to look after when they became ill, as well as their mother. One hemorrhaged and I took her to hospital, which is now a big hotel at Hyde Park Corner. The other lady was trying to clear a drain with caustic soda, got it all over her hands; I got the doctor for her. I told Mrs Rosse’s daughter, Esther Macdonald, who was married to a doctor and lived in Surrey, and all she did was turn up, take the ration books for her mother and her aunt, drew the rations and downstairs they had some very old furniture, Jacobean, and she took it out and sold it. When those two ladies died, they left a will, which I was to be included in, for a certain amount of money. Esther disputed it so my husband and I got a solicitor and we got a small sum of money. She wanted me to run the shop which I did, she used to come take money out of the till, leave an I.O.U.

During air raids, our shop windows were blown out, the shop across the road got a firebomb and the two corner shops, one a hat shop the other a butchers, were completely destroyed, leaving just a hole. We used to ask the customers if they wanted to leave during an air raid, but mostly they would say to continue so we worked throughout air raids. The shop closed at seven and I had to walk to Peckham to become an air raid warden, four miles, which took me three hours. You reported to the post, and if they said you weren’t needed you could go home and they would come and get us if necessary. This didn’t often happen! The wardens were responsible for the number of people in the houses and we had to find out if they were in the houses or in the garden shelters at the back and often they were in the pubs!

My husband Fred was in Caterick first in 1939 and then he was sent to Egypt in 1940, where he was in some caves in the desert. The caves were originally used to extract stones for the pyramids. He came home in 1945, and he was sent to Hampshire. And he was there until he was discharged a year later and worked for North Thames Gas as a communications officer. He never spoke about his time in the army. He only remembered the worst bits and he wouldn’t tell me about those.

I only got two letters from him during this time — they didn’t get through. Maybe they got put on a ship or a plane? I used to send him parcels with brushes and polish, toothpaste and socks, which is what he wanted as the army didn’t supply them. And through the bank sent him a draft as his watch got stolen. He got most of my letters, even though they took a long while.

Until my husband came home, my mother had the ration books and she’d collect the rations until we moved to Victoria and she’d go to the butchers in Warwick way — the maypole.

My mother subsequently became very ill with cancer and she was taken to the Old Westminster Hospital. I used to rush and visit her and she died there after a year.

I’m originally from great Yarmouth in Norfolk and that’s where I had my first air raid when I was eighteen. I moved to London with my family because the house was bombed and we lived first for eighteen months in Asylum Road, until we got bombed there, then we moved to Clifton crescent, again in Peckham, for less than a year until once more we were bombed out, so we went to Whittington road which my mother found.

As I’d been left half the hairdressers, we bought the other half from Esther, modernized it and ran it until I was sixty. My husband made me retire then, and dragged me off to the social services as I hadn’t realized I could get a pension. So now I go to the Post Office every week and draw my pension.

On VE Day a lot of the streets had street parties.

These are some of the things I experienced in my apprenticeship we had a metal container over gas ring which was filled with green soap

which was our shampoo the water to the basins came from a large metal tank which was heated with two large open gas rings. One lunch time I was invited to a friend’s house, when I retuned water was pouring out of the door. The water tank had burst. My husband helped Miss Arnott to obtain and install small electric water heaters by each baisin which were a great improvement.

On the ground floor were wooden cubicles painted green and orange. The shop windows had glass sliding panels which I had to clean. The cubicle curtains which had to drawn so no one person could the other ito shampoo thnen be watch and hand things to the first asstiant