High Explosive Bomb at Westferry Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Westferry Road, Millwall, London Borough of Tower Hamlets, E14, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

In 1939, I was ten years old and lived with my family in a terrace house in Catlin Street, off Rotherhithe New Road, Bermondsey, South London.

I had two older brothers, John and Percy, two younger sisters, Iris and Beryl and a little brother Ron. My mother was expecting another baby in December who was to be my sister Sheila.

During the summer, war-scare was the main topic on the radio and in the newapapers, lots of preparations for Civil Defence were started.

Everyone was issued with a Gas-mask in a cardboard box with a shoulder string. Children under five got a "Mickey-mouse" model in pink rubber with a blue nose-piece and round eye-lenses.

There was a special one for infants, which completely enclosed the baby, and came with a hand-pump for Mum to operate.

It was a time of some excitement for us schoolchildren, clouded a little by fear of the unknown. All I knew about war was what mum and dad had told me about the Great War, when dad was a soldier and mum's family were bombed out in a Zeppelin raid when they lived at New Cross, Deptford.

Of course, things didn't happen all at once, you went to collect your gas-mask when it was your family's turn. Similarly, throughout the summer, gangs of workmen came round erecting Anderson shelters in the back gardens, street by street, a slow process. So the main topics of conversation at school were: "Got your gas-mask yet?" Or perhaps: "They've dug a big hole in our back-garden and are putting the shelter in today." This made one quite a celebrity, with looks of envy from others who were still shelter-less.

It was in the summer holidays when we got our shelter, so I didn't get a chance to gloat. Brother Percy remembers getting timber and plywood off-cuts from the local timber-yard to floor it out, but we were never to use this shelter in an air-raid as we moved to our new home in Galleywall Road before the Blitz started.

On the Wednesday of the week before War was declared in September, us school-children were told to pack our things and bring them with us to school next day as we were going to be evacuated from London. Although John and Percy went to different schools, they were allowed to come with Iris, Beryl and myself in order to keep the family together.

We duly turned up next morning with our little bits of luggage and had a label with our details on it tied to our coat lapels. Some of the kids were a bit quiet and weepy, but most were excited and chattering, speculating about where we were going.

Eventually, we walked in a long crocodile all the way to the back entrance of Bricklayers Arms goods station in Rolls Road. An engine-less train stood beside the wooden platform in the dim light of the goods-shed. We all got in and waited for what seemed an interminable time, then we were ushered out again and marched back to school. Our evacuation had been cancelled and we were sent home again. We never heard the reason why, but I think it must have been something to do with the railway being busy with military traffic.

On Friday the 1st of September, we assembled again at school early in the morning and walked in our procession to South Bermondsey Station, just a short distance away, each wearing a label, gas-mask case on shoulder and carrying a case or bag.

This time it was for real, and there was a special electric train waiting at the station, with plenty of room for all of us, but to the consternation of the big crowd of Mums and Dads who came to see us off, no-one could tell them where we were going, so it was a mystery ride.

The old type train carriages had seperate compartments and no corridor, so there were no toilets. I don't remember there being any problems in my compartment, although I was bursting by the time we arrived at our destination, but I expect there were some red faces in the rest of the train, especially among the younger children.

The journey took for ages, as we were shunted about quite a bit, and by mid-day we were getting hungry.

At last the journey ended and we found ourselves at Worthing, a seaside resort on the Sussex coast

Tired and hungry, we were herded into a hall near the station and seperated into groups, family members together.

Some of us were given a white carrier-bag containing rations, which I believe was meant to be given to the people we were billeted on to tide us over, but following the example of my friends, I dived into mine to see if there were any eatables. All the bag contained was a tin of condensed milk, a tin of corned-beef, a packet of very hard unsweetened plain chocolate that tasted like laxative, and two packets of hard-tack biscuits, which were tasteless and impossible to eat while dry. I think they must have been iron-rations left over from the first World-War.

A Billeting Officer took charge of each group and took us round the streets, knocking at doors until we were all found a billet This was a compulsory process, and some of the Householders didn't take too kindly to having children from London thrust upon them, so there were good Billets and not so good ones.

Some would only take boys or girls, but not both if they only had one spare room, so families were split up.

It was all a big adventure for me, and I wanted to stay with my schoolmate, Terry. We had teamed up on a school holiday earlier in the summer, and were good friends.

My two brothers were put into the same billet, and my sisters together in the house next door. They were all well looked after, but Terry and I were the luckiest

We went to stay with Mr and Mrs L at their house in Ashdown Road, Worthing. They had a teenage son and daughter, and Granny L lived in her own room upstairs.

Auntie Mabel, as we came to know Mrs L, was a lovely person. She treated us as if we were her own, and her Husband and the rest of the family were all good to us.

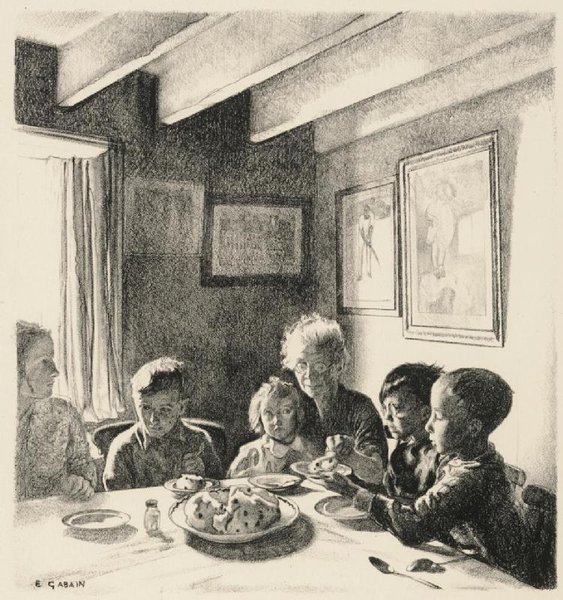

Auntie Mabel was always cooking and baking, and made sure that we ate plenty. Her Husband, who I will call Uncle L as I forget his first name, was a Builder and Decorator with a sizeable business and had men working for him.

He'd spent most of his life in the Royal Navy, and served on the famous Battleship, HMS Barham, during the first World War when it was in the Battle of Jutland. He had many tales to tell of his sea-faring life, and lots of photographs which enthralled me and made me want to be a sailor when I grew up.

His son, I think his name was Dennis, had only recently left school and started work. He became our special friend, and took us on regular outings to the Cinema, sporting events and the like.

His sister was a couple of years older. I don't remember much about her, except that her name was Edna. She was very pretty and worked at the local Dairy.

Granny L was very old. I believe she must have been in her eighties at the time. She used to wear long dresses, and wore her grey hair in a huge bun on top of her head.

She looked just like one of those ladies seen in old pictures of Victorian scenes.

She was very nice, and reminded me a little of my own Gran back in London.

We immediately hit it off together and became firm friends. She had lots of curios and pictures. Her husband had been a Captain on one of the old Sailing-Ships before the age of steam, and sailed all over the world.

He'd spent a lot of time in the South- Seas, and brought many souvenirs home. I remember some lovely Corals in a glass-case, and a couple of the largest eggs I'd ever seen. Granny L said they were Ostrich eggs, and came from Africa.

The L Family were Chapel-goers, and took us to the Service with them every Sunday evening.

It was quite an experience, being so informal after the strict Church Services we were used to at home.

Auntie Mabel looked rather grand in her Sunday clothes.

She used to wear her best coat and a big hat, which I thought was shaped like an American Stetson with trimmings. These hats were fashionable at the time, and it looked good on Auntie Mabel. She was a nice-looking lady, always smiling and joking.

It was a lovely summer that year, and the weather was fine and sunny when we went to Worthing, so we made the most of it and were on the beach on the morning of Sunday September 3.

We heard that Mr Chamberlain had announced on the radio at eleven o'clock that we were at war with Germany. Not long afterwards, we heard the wail of Air-raid Sirens, then the sound of aircraft engines, but it was one of ours and soon the All-clear sounded.

In the ensuing days and weeks, everything seemed to carry on as normal, the Seafront and beaches were open and without any defences, although this was all to change in the coming months.

The following weekend, it was still warm and sunny, and our little group were walking along the crowded Sea-front, when who should appear in front of us, but my Mother, and Auntie Alice, her younger sister.

They had both been evacuated from London as expectant mothers a few days before. Mum had heard rumours that our school had gone to Worthing, but our letters home hadn't arrived by the time she left, so she wasn't sure.

It was by a lucky chance that they'd come to the same place, and they knew we'd be at the Sea-front sometime if we were here, so they kept a constant look-out.

Mum and Auntie Alice were billeted quite a long way from us, so we only saw them at weekends, but it gave us a feeling of security to know that Mum was around.

However, she only stayed at Worthing for a couple of months or so until the first war-scare died down, although we had to stay on as there were no Schools open in London.

Our education carried on as normal at the local Junior School. One thing that stands out in my mind is that after we'd been there a while we were told by the Class-Mistress to write an essay on the most interesting thing we'd found while at Worthing.

At the weekend before, Dennis had taken us up on the South Downs behind the town to Chanctonbury Ring, a large circular clump of ancient trees on top of a hill.

There were prehistoric remains in the vicinity, and it was dark and eerie under the trees, the ring was reputed to be haunted.

There were quite a few tales going the rounds at school about it, especially the one about what happened to you if you ran round the ring three times, then lay down and closed your eyes.

You were supposed to experience all manner of weird things. On reflection, I think one would have needed to lie down after running round the ring three times. You'd have ran at least a couple of miles!

Needless to say, my essay was about our trip to this place, and I was all-agog to read it out in class when the Mistress randomly selected one of us to do so.

However, she chose Ronnie Bates, another friend of mine who lived just round the corner at home, and I can still see the look of horror on the Mistress's face as Ronnie proceeded to read out his lurid essay about the goings on at the local Slaughterhouse, which was on his way home from school, and seemed to fascinate him.

He often managed to get a peep inside, it was an old-fashioned place, and opened on to the street with just a small yard for the animals going in.

In the run up to Christmas, they formed a choir at school, and I was chosen to be a member. Then we were told that the BBC were organising a children's choral concert to be broadcast from a local theatre just before the Christmas Holidays.

Choirs from all the many London schools evacuated to Sussex taking part.

When the day came, we spent all the morning at the Theatre rehearsing with the BBC Orchestra, and Chorus-Master Leslie Woodgate. He was quite a famous man, well known on the radio, and really good at his job, so he got the best out of us.

Even I felt quite emotional when the concert ended with everyone singing "Jerusalem" acccompanied by the full Orchestra.

What seemed strange to me was the way Mr Woodgate mouthed the words at us as we sang, he looked quite comical conducting at the same time.

There was a sort of Lamp-standard with a naked red bulb on the front of the stage, and when it came on, we were on the air!

The Concert was interspersed with orchestral music and soloists as well as our singing. One item that I particularly recall was a piece by a lady Viola player, accompanied by the orchestra.

I had never heard of the Viola before, I just thought they were all Violins except for Cellos and Double-Basses.

The rich tone of the instrument impressed me very much, although at the time I was dying for the Lady to finish playing so that I could dash out to the toilet.

We were afterwards told that the Concert was a big success, but none of us were able to hear it on the radio. It was a live broadcast, as most radio programmes were in those days.

The weekend after school broke up for the holidays, Dad came down in a friend's car and took us home for Christmas.

I didn't know it when we left, but that was the last time I was to see Auntie Mabel and her family, as we didn't go back to Worthing after the holiday, but stayed at home in Bermondsey.

It was the time of the "phony war". Many evacuees returned to London, as a false sense of security prevailed.

Our parents allowed us to stay at home after much worrying. We heard that our School was re-opening after the holidays, and as I was due to sit for the Scholarship, I'd be able to take it in London.

This exam was the forerunner of today's eleven-plus, and passing it would get me a place at one of the private Grammar-Schools with fees paid by the London County Council.

To my great regret, in all the turmoil of events that followed with the start of the Blitz, and my second evacuation from London to join my new School, I didn't keep up contact with Auntie Mabel and her family. I hope they all survived the war and everything went well for them.

{to be continued}.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Home again in Bermondsey after the few months sojourn in Worthing, I saw my new baby sister Sheila for the first time. She'd been born on December 5, and Mum was by then just about allowed to get up.

In those days, Mothers were confined to bed for a couple of weeks after having a baby, and the Midwife would come in every day. In our case, the Midwife was an old friend of my mother.

Her name was Nurse Barnes. She lived locally, and was a familiar figure on her rounds, riding a bicycle with a case on the carrier. She wore a brown uniform with a little round hat, and had attended Mum at all of our births, so Mum must have been one of her best customers.

That Christmas passed happily for us. There were no shortages of anything and no rationing yet.

When we found that our school was re-opening after the holidays, Mum and Dad let us stay at home for good after a bit of persuasion.

I was a bit sad at not seeing Auntie Mabel again, but there's no place like home, and it was getting to be quite an exciting time in London, what with ARP Posts and one-man shelters for the Policemen appearing in the streets. These were cone shaped metal cylinders with a door and had a ring on the top so they could easily be put in position with a crane. They were later replaced with the familiar blue Police-Boxes that are still seen in some places today.

The ends of Railway Arches were bricked over so they could be used as Air-raid Shelters, and large brick Air-raid Shelters with concrete roofs were erected in side streets.

When the bombing started, people with no shelter of their own at home would sleep in these Public Air-raid Shelters every night. Bunks were fitted, and each family claimed their own space.

There was a complete blackout, with no street lamps at night Men painted white lines everywhere, round trees, lamp-posts, kerbstones, and everything that the unwary pedestrian was likely to bump into in the dark.

It got dark early in that first winter of the war, and I always took my torch and hurried if sent on an errand, it was a bit scary in the blackout. I don't know how drivers found their way about, every vehicle had masked headlamps that only showed a small amount of light through, even horses and carts had their oil-lamps masked.

ARP Wardens went about in their Tin-hats and dark blue battledress uniforms, checking for chinks in the Blackout Curtains. They had a lovely time trying out their whistles and wooden gas warning rattles when they held an exercise, which was really deadly serious of course.

The wartime spirit of the Londoner was starting to manifest itself, and people became more friendly and helpful.It was quite an exciting time for us children, we seemed to have more things to do.

With the advent of radio and Stars like Gracie Fields, and Flanagan and Allen singing them, popular songs became all the rage.

Our Headmaster Mr White, assembled the whole school in the Hall on Friday afternoons for a singsong.

He had a screen erected on the stage, and the words were displayed on it from slides.

Miss Gow, my Class-Mistress, played the piano, while we sang such songs as "Run Rabbit Run!" "Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree," "We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line," and many others.

Of course, we had our own words to some of the songs, and that added to the fun. "The spreading Chestnut Tree" was a song with many verses, and one did actions to the words.

Most of the boys hid their faces as "All her kisses were so sweet" was sung. I used to keep my options open, depending on which girl was sitting near me. Some of the girls in my class were very kiss-able indeed.

One of the improvised verses of this song went as follows:

"Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree,

Mr Chamberlain said to me

If you want to get your Tin-Hat free,

Join the blinking A.R.P!"

We moved to our new home, a Shop with living accomodation up near the main local shopping area in January 1940.

Up to then, my Dad ran his Egg and Dairy Produce Rounds quite successfully from home, but now, with food rationing in the offing, he needed Shop Premises as the customers would have to come to him.

His rounds had covered the district, from New Cross in one direction to the Bricklayers Arms in the Old Kent Road at Southwark in the other, and it was quite surprising that some of his old Customers from far and wide registered with him, and remained loyal throughout the war, coming all the way to the Shop every week for their Rations.

Dad's Shop was in Galleywall Road, which joined Southwark Park Road at the part which was the main shopping area, lined with Shops and Stalls in the road, and known as the "Blue," after a Pub called the "Blue Anchor" on the corner of Blue Anchor Lane.

It was closer to the River Thames and Surrey Docks than Catlin Street.

The School was only a few yards from the Shop, and behind it was a huge brick building without windows.

In big white-tiled letters on the wall was the name of the firm and the words: "Bermondsey Cold Store," but this was soon covered over with black paint.

This place was a Food-Store. Luckily it was never hit by german bombs all through the war, and only ever suffered minor damage from shrapnel and a dud AA shell.

Soon after we moved in to the Shop, an Anderson Shelter was installed in the back-garden, and this was to become very important to us.

As 1940 progressed, we heard about Dunkirk and all the little Ships that had gone across the Channel to help with the evacuation, among them many of the Pleasure Boats from the Thames, led by Paddle-Steamers such as the Golden Eagle and Royal Eagle, which I believe was sunk.

These Ships used to take hundreds of day-trippers from Tower Pier to Southend and the Kent seaside resorts daily in Peace-time. I had often seen them go by on Saturday mornings when we were at Cherry-Garden Pier, just downstream from Tower Bridge. My friends and I would sometimes play down there on the little sandy beach left on the foreshore when the tide went out.

With the good news of our troops successful return from Dunkirk came the bad news that more and more of our Merchant Ships were being sunk by U-Boats, and essential goods were getting in short supply. So we were issued with Ration-Books, and food rationing started.

This didn't affect our family so much, as there were then nine of us, and big families managed quite well. It must have been hard for people living on their own though. I felt especially sorry for some of the little old ladies who lived near us, two ounces of tea and four ounces of sugar don't go very far when you're on your own.

I'm not sure when it was, but everyone was given a National Identity Number and issued with an Identity Card which had to be produced on demand to a Policeman.

When the National Health Service started after the war, my I.D. Number became my National Health Number, it was on my medical card until a few years ago when everything was computerised, and I still remember it, as I expect most people of my generation can.

Somewhere about the middle of the year, I was sent to Southwark Park School to sit for the Junior County Scholarship.

I wasn't to get the result for quite a long while however, and I was getting used to life in London in Wartime, also getting used to living in the Shop, helping Dad, and learning how to serve Customers.

We could usually tell when there was going to be an Air-Raid warning, as there were Barrage Balloons sited all over London, and they would go up well before the sirens sounded, I suppose they got word when the enemy was approaching.

Silvery-grey in colour, the Balloons were a majestic sight in the sky with their trailing cables, and engendered a feeling of reassurance in us for the protection they gave from Dive-Bombers.

The nearest one to us was sited in the enclosed front gardens of some Almshouses in Asylum Road, just off Old Kent Road.

This Balloon-Site was operated by WAAF girls. They had a covered lorry with a winch on the back, and the Balloon was moored to it.

I went round there a couple of times to have a look through the railings, and was once lucky enough to see the Girls release the moorings, and the Balloon go up very quickly with a roar from the lorry engine, as the winch was unwound.

In Southwark Park, which lay between our Home and Surrey-Docks, there was a big circular field known as the Oval after it's famous name-sake, as cricket was played there in the summer.

It was now filled with Anti-Aircraft Guns which made a deafening sound when they were all firing, and the exploding shells rained shrapnel all around, making a tinkling sound as it hit the rooftops.

The stage was being set for the Battle of Britain and the Blitz on London, although us poor innocents didn't have much of a clue as to what we were in for.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by angaval (BBC WW2 People's War)

It is September 1940 and I am returning from Chrisp Street Market with my mother. I'm nearly seven and I've come back to London after being evacuated to Glastonbury during the 'phoney war'. It's a lovely warm evening and my mum is anxious to get back home with her shopping.

As we begin to turn into Brunswick Road, we hear the sound of gunfire - not unusual, as we live near the East India Docks and there is frequent gunnery practice. But then we hear the planes and the air raid sirens. ARP wardens are running about blowing whistles, shouting, 'Take cover, take cover!' We start running the last few yards home.

My dad is panicking and my nana (who speaks little English) is hysterical. We then all bolt into the Anderson shelter in the back yard, just as the first bombs start exploding. My Dad hates the Anderson as it's always full of spiders and he's scared of them. The noise is horrendous. Every time a bomb falls near, everything shakes. Above us there is the 'voom, voom, voom' sound of the planes. The ack-ack guns make a hollow booming noise and the Bofors make a rapid staccato rattle. It seems to go on for hours and then, suddenly, there is a pause, then the 'all clear'.

Stunned by the noise, we emerge. The house is still standing and doesn't seem damaged. We go out through the front door to see a scene which even now I recall as vividly as when it happened. The entire street is choked with emergency vehicles - ambulances, fire engines - all clanging their bells. The gutters and pavements are full of writhing hoses like giant snakes, and above... the sky. The sky - to the south, still a deep, beautiful blue, but to the north a vision of hell. It is red, it is orange, it is luminous yellow. It writhes in billows, it is threaded through with wisps and clouds of grey smoke and white steam. All around there are shouts and occasional screams, whistles blow and bells clang.

The neighbours stand around in small groups. They talk quietly and seem as dazed as us. Apparently most of the flames are from the Lloyd Loom factory down the road, which has taken a direct hit. The gutters run with water, soot and oily rainbows and the reflections of the fiery sky. Our respite does not last long. About 20 minutes later, another alert, we are back in the Anderson, and it all begins again.

The noise makes my knees hurt. When I tell my mother, she laughs and says it's growing pains. Maybe, maybe, but for the rest of the war; whenever there was a raid my knees always ached!

Contributed originally by OrangePip (BBC WW2 People's War)

I still remember one night during the blitz when the air raid siren sounded and my Mum was rushing around telling my brother Ronnie and I to get some clothes on and get down to the underground shelter. We could hear the doodle bugs overhead and as children (I was about 7 years old and my brother Ronnie was about 9 years old) we had no fear. We didn't realize at the time the severity of the situation Anyway, Mum kept yelling at us to get our shoes and clothes on and get down to the underground shelter. Ronnie ket trying to tell Mum he couldn't get his Wellingtons on. She would not hear of it and yelled at him some more to put them on. Well poor Ronnie got one of the Wellingtons on but could only get his foot half way down the other one. We rushed down the stairs, we lived in Adams Gardens Estate, Rotherhithe, London, S.E.16 (a block of flats) and Ronnie hobbled and hobbled to the underground shelter and when we got there, Mum was very upset with Ronnie because he was not doing as he was told to put his "Wellies" on - and needless to say, when she found out the reason for this, she felt so bad at yelling at Ronnie because it turned out that his Wellington boots were full of CONKERS that he was saving. Oh, I still remember the look on Mum's face when she found out the reason. It was priceless!

Joyce Gilley (formerly Bentley)

Contributed originally by Leicestershire Library Services - Countesthorpe Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jim Humphreys. He fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

TOPICS

1 EVACUATION

2 CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

3 FATHERS ROLE

4 SHELTERS

5 V.WEAPONS

THESE ARE TO BE FOUND IN SEPARATE ENTRY UNDER 'JIM HUMPHREYS - PART 2 OF 2'

1 EVACUATION

I was born in South London in October 1935 to the sound of Bow Bells. In 1938 my parents, younger sister and myself moved to Grosvenor Terrace, Camberwell, and lived there until the 1960s. Soon after war was declared we were evacuated to an area 10 miles from Swansea.

I have no recollection as to how we arrived there, all that I remember is that we were standing outside a café, together with my family, my mother's mother and 3 of her children plus about 3 suitcases. Next to the café was the local bus terminal to Swansea.

The garden had some vegetables. Grandmother was advised to make bread as there was no guarantee that the deliveryman would appear at a regular time.

To get to school we sometimes had a bus; more often we had to walk through the woods. We later experienced some rumbles and bangs during the night. We, the children, were told that it was nothing to worry about. We later discovered that after the bangs etc., a certain area of the sky was always a reddish colour. We were told by our older school friends that Swansea had been bombed again.

Not far from the bus terminal was a steep cliff edge with a path down to the sandy beach. To get to the sea we had to climb over some rocks and sometimes on these rocks and at the water's edge was this thick black sticky stuff. Once on your clothes it was very difficult to remove. We later learned that this was crude oil from ships in the channel.

An uncle and aunt, who were too old for the junior school that I attended, managed to get a job at the local farm. I have no recollection of coming back to London, but we apparently had been away for about 6 months.

Our second evacuation was to Leicester. I can remember going to the junior school along our street with my mother, two sisters and father. Father carried a suitcase and I had a parcel tied to my belt and wrist, and of course my gasmask around my neck. All the children had a luggage label tied to a buttonhole or some place where it could be seen. We were marched with a lot of other families to the main road where we waited for trams. The trams came in a long line and when our names were called, we had to get onto a certain tram. Dad did not get on. After having our names checked, some families got on and others got off.

At last we were away. There was lots of crying by the mums and children including mine. I dont remember me crying though. We ended up in Leicester station. We were asked every time a train was due, "once again in case you fall, please keep against the wall". We were there for ages; trains were arriving; some families got on and some got off. Eventually we were lead to a line of busses. After a lot of checking names again we set off. I know we ended up at a school in Earl Shilton. We were given blankets, pillows and told that there were mattresses where we would sleep.

It was here I experienced my first shower. We used to stand under the shower and get wet, then we soaped our stomachs and chest, lay on the floor against the wall and pushed off with both feet skidding across the width of the shower area. There were collisions of course bit no real damage was done. We were at the school (now known as Bell View School for Girls) for about 10 days. We were then taken down to a shoe factory on the corner of the main road and New Street. We were to lodge in what was then the night watchman's accommodation. Another woman and her two young daughters joined us. She had told the authorities that she was related to us. In fact they lived further down the street and she thought it was better to live with somebody that you knew than with total strangers.

We were made very welcome by the factory staff and workers, in as much that they offered my mother and this other woman a part time job each. My mother accepted but the woman did not. This later led to confrontation because she was quite happy for my mother to feed her and her 2 daughters.

There was quite a large family living next door and they were very good to us. They showed us where the best fruit was for scrumping and where the best play areas were. We in turn showed them where the sheets of leather were kept.

At weekends when it was wet and we were not allowed into the street, we would enter the factory, collecting on our way a reasonable size sheet of leather, take it to the very top of the building where there was this track with rollers. We would place the leather onto the rollers and let it go and chase it all the way to the bottom. Somebody then had the bright idea of sitting on top of the leather. We fell off on many occasions before we perfected the run and apart from a few minor cuts and bruises no damage was done.

In the mornings we used to go to the little school at the end of the village. After school we would walk to the local recreation area for about an hour. By the time we got home Mum would have finished her shift and then we would muck in and get tea. It was about a month after the woman and Mum had the row that she finally accepted a job at the factory but asked not to be near where Mum was.

I cant recall having many air raids and people came round to make sure that there were no lights showing. There was one incident that I remember very well, and that was when everybody was asked to show as much light as possible. We later learned that there were some aircraft that had some problems, fully loaded with fuel and bombs and if they had to crash they did not want to land on populated areas.

One day our father arrived unexpectedly and said that it was now considered safe to return to London. We left unwillingly about a week later. We had a great time for about 9 months.

2 CHILDHOOD MEMORIES

I cant remember much about the start of the war except my father used to disappear on certain evenings. It was when we returned from our evacuation from South Wales that our street looked somewhat different. Passed the Infant School and not far from where we lived, there were some 4 houses that had fallen down. Then on our way to where my mother's mother lived there were some more and even across the road there were more houses that had fallen. I was told that air-planes had dropped bombs and this was why the houses were like they were. I was also told that we were not to go in them as they were dangerous and not to be played in.

At the bottom of our street there was an old wooden railway bridge and when the trains went across it, the noise was such that it used to keep us awake. Later we found out that the noise was to do with an anti-aircraft gun on the rails and it used to go to the areas that were being bombed.

After school there was not a lot to do, apart from collecting shrapnel (bits of metal from either bombs or anti-aircraft shells). Some cannon shells were also a collectable item. Later on there were the Butterfly Bombs (anti-personnel devices). These had a pair of little propeller blades and they used to float down so they did not explode on impact. (You touched them and they did!).

There was no television and no cinemas that we could go to at that time of the evening, so we had to invent things. There were about six or seven of us lads about the same age. One of them found an old motorcycle tyre and we organised races up and down the street. While one lad rolled his tyre up and down the others counted. We all took turns, the fastest being declared the winner.

Other tyres were found and in a short time we all had one. We used to use plaster from the ruins to mark out hopscotch grids, positions of goals and penalty areas for football. Coats or pullovers were used to mark the width of the goal down the middle of the road and very rarely did we have to remove them. A ball game we used to play was called Cannon. Two teams were formed and four pieces of firewood were placed against a wall in the form of a cricket wicket. One team would try to dislodge this wicket with a tennis ball (team A), if successful they would scatter away from the area and try to resurrect the wicket. However team B would try to stop this happening by trying to hit the members of team A with the tennis ball. Once hit by the ball you were out of the game until the game was restarted. Another game was rounders.

During the war years we used to have what was known as double summer time. At 10PM in the evening it was still very light and at times we were so engrossed in games that time was forgotten. These games would be interrupted by parents or others to remind us that it was late. It would be about this time of day we would watch the bombers flying quite high going to their targets. At times we would wonder if the children where the bombs were going to be dropped were being treated as we were.Were they getting tear gas dropped on them; and were they in the playground being shot at?

We were not allowed into the playground while there was an air raid on. When the all clear went, a teacher used to go out to see if it was safe. The following day about lunchtime the aircraft would return, some of them quite high but others very low. We used to stop what we were doing and marvel on how they were still flying in the condition that they were in. Some had engines stopped while others had tail parts missing and others had such large holes that you could see right through them. We also saw the vapour trails when the dogfights between Allied and the German fighter planes occurred.

On V.E. and V.J. days everybody local erected huge bonfires where the bombed houses had been to celebrate the end of the war.

3. FATHERS ROLE

I was born in London in 1935 within the sound of Bow Bells. In 1938 my parents, younger sister and myself moved to Grosvenor Terrace, which is in S.E London.

Before the war my father was a very keen football player and had taken some first aid courses, his job at that time was that of a bricklayer.

At the start of the war he volunteered as an Air Raid Warden. When he was called for the armed services, he was rejected on the grounds that with his knowledge he would be of better use in the Heavy Rescue, which was being set up.

He was stationed at a disused girls school about 3 miles from where we lived and so was able to come home when things were quiet. He accepted the fact that at times he would not be home as frequently as he liked or there may come a time when he might not at all. I was given the task, that in his absence, there were various jobs to be performed. Feeding the chickens, collecting the eggs, if there were any, and tickling the flowers on the plants with a fine paint brush. This was required because there were no or very few bees to do it for us. We were fortunate that both sets of grandparents lived in the same street, therefore if we ran short of anything they were on hand to help.

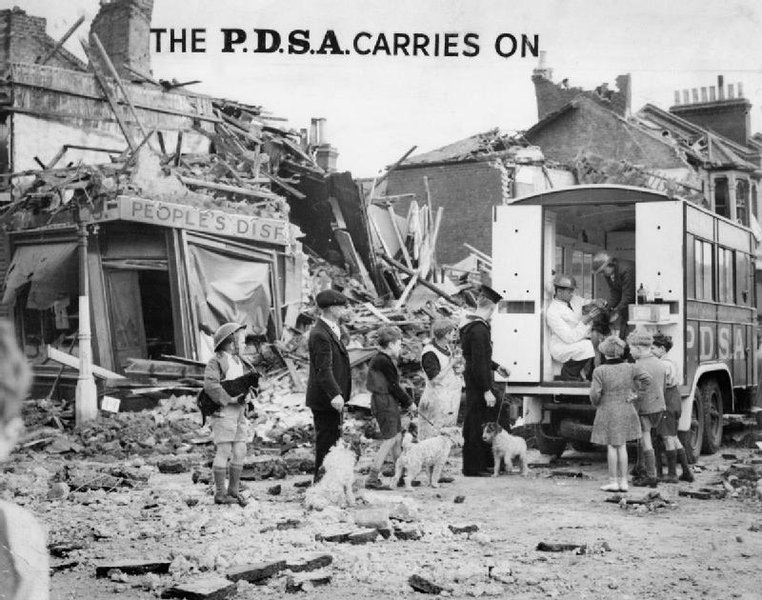

The function of the Heavy Rescue was to be on the scene as soon as possible after any bombs were dropped and to organise any rescue procedures that were required. This also involved the required ambulances and fire engines. He was soon promoted to be the team leader with the responsibility of having several teams under his leadership. His duties were to organise the scene and then move to another area and do the same until all areas were doing what they could in the circumstances.

There were times when we would not see him for days and then weeks;

Mother did not know whether he was alive or not. It was at this time that he started smoking. He developed into a very heavy smoker. As there was no chance of him getting regular supplies of cigarettes himself, and as they were in short supply, it was down to Mum and I to collect and supply them. The allowance was 100 per week. This satisfied dad for a short period of time. Eventually we were collecting 500 a week, they were the strongest that were on the market. He would use 1 match per day.

On the few occasions that we were out together he would make sure that together with the packet he was using he would have at least 2 more full packets. If he had to start a fresh packet while we were out, he would purchase another before we arrived home. While we were evacuated to Leicester he came to visit us. He had developed two growths in his throat. I was allowed time off from school to fetch ice so that he could put this around his throat to help him swallow. When these growths finally subsided he advised Mum not to purchase any more cigarettes. He put on a lot of weight and eventually died at the age of 92.

At the bottom of the playground of this school was a swimming pool. In the bottom of this empty pool there was placed a Master Searchlight. This had a very powerful beam and was used to locate the enemy aircraft. Once the planes were lit up the secondary or less powerful searchlight would take over allowing the Master Searchlight to look for other targets. The enemy realised the importance of this searchlight and tried to bomb it on many occasions but were unsuccessful because the crew used to move it to a different location every evening.

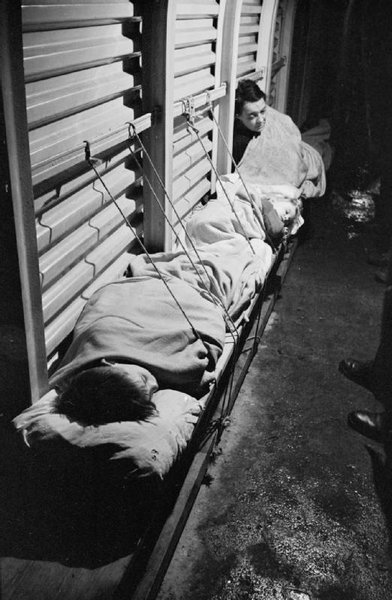

Because of the lack of ambulances, a lot of injured were laid along the pavement if it was safe to do so. If they had had to have severe bleeding stopped by very tight dressings, the time of the application of the dressing was marked in blood on their forehead. If a medic or firstaider noticed that the time of application had exceeded 15 minutes then the wound would be undone, allowed to bleed and then tightened up again and the new time marked on the forehead.

His main area of work was in the City of London or the Docklands where the bombing was more or less concentrated. A lot of buildings used to collapse and therefore block roads so that emergency crews could not get their vehicles to where they were required. In these incidents the crews had to carry their stretchers and hoses around or between the ruins before they could render any assistance.

One occasion (we learned later) there was a very large fire in the docklands, which he was trying to organise. He was called away to another emergency and when he returned within 15 minutes he found that more bombs had been dropped across the road where his fire was, causing a warehouse to collapse onto many fire engines and ambulances, killing the majority of their crews.

On one of his rare days off, he took me to a place some streets away from were we lived to show me something that had happened a week or so previously.

A parachute was seen coming down by the local A.R. Warden. With some colleagues they stood under the tree were the parachute was tangled within the branches. They called up but received no answer. Assuming the airman was either dead or injured a guard was placed until daylight. To their horror the airman was in fact a large metal cylinder, which turned out to be a landmine. The area was immediately evacuated until it could be defused.

The King and Queen were frequent visitors to bombed areas within days of the raids taking place, as was the Prime Minister. They also used to visit the school that was being used as my father's base.

My father was mentioned twice in despatches for courage and bravery.