Bombs dropped in the borough of: Camden

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Camden:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 813

- Parachute Mine

- 16

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Camden

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by vcfairfield (BBC WW2 People's War)

Over the Seas Two-Five-Four!

We’re marching right off,

We’re marching right off to War!

No-body knows where or when

But we’re marching right off

We’re marching right off - again!

It may be BER-LIN

To fight Hitler’s KIN

Two-fifty-four will win through

We may be gone for days and days — and then!

We’ll be marching right off for home

Marching right off for ho-me

Marching right off for home — again!

___________________________

Merry-merry-merry are we

For we are the boys of the AR-TIL-LER-Y!

Sing high — sing low where ever we go

TWO-FIVE-FOUR Battery never say NO

INTRODUCTION

The 64th Field Regiment Royal Artillery, Territorial Army has roots going back to the 1860’s. It first saw action in France during the Great War 1914 to 1918 when it took part in the well known battles of Loos, Vimy Ridge, River Somme, Ypres, Passchendale, Cambrai and Lille.

Its casualties numbered 158 killed.

Again in the Second World War it was called upon to play its part and fought with the 8th Army in Tunisia and then with the 5th and 8th armies in Italy. It was part of the first sea borne invasion fleet to land on the actual continent of Europe thus beginning its liberation from Nazi German domination. Battle honours include Salerno, Volturno, Garigliano, Mt Camino, Anzio, Gemmano, Monefiore, Coriano Ridge, Forli, Faenza, R. Senio Argenta.

Its peacetime recruits came mainly from the Putney, Shepherds Bush and Paddington areas of London up to the beginning of World War II. However on the commencement of hostilities and for the next two years many men left the regiment as reinforcements and for other reasons. As a result roughly one third of the original Territorials went abroad with the regiment, the remainder being time expired regular soldiers and conscripted men.

Casualties amounted to 84 killed and 160 wounded.

In 1937 I was nineteen years old and there was every indication that the dictators ruling Germany in particular and to a lesser degree Italy, were rearming and war seemed a not too distant prospect. Britain, in my opinion had gone too far along the path of disarmament since World War I and with a vast empire to defend was becoming alarmingly weak by comparison, particularly in the air and on land. It was in this atmosphere that my employers gathered together all the young men in their London office, and presumably, elsewhere, and indicated that they believed we really ought to join a branch of the armed forces in view of the war clouds gathering over Europe and the hostile actions of Messrs Hitler and Mussolini. There was a fair amount of enthusiasm in the air at the time and it must not be forgotten that we British in those days were intensely proud of our country. The Empire encompassed the world and it was only nineteen years since we had defeated Imperial Germany.

The fact that we may not do so well in a future war against Germany and Italy did not enter the heads of us teenagers. And we certainly had no idea that the army had not advanced very far since 1918 in some areas of military strategy.

In the circumstances I looked round for a branch of the forces that was local to where I lived and decided to join an artillery battery at Shepherds Bush in West London. The uniform, if you could call the rather misshapen khaki outfit by such a name, with its’ spurs was just that bit less unattractive than the various infantry or engineer units that were available. So in February 1937 I was sworn-in, with my friend Ernie and received the Kings shilling as was the custom. It so happened that soon afterwards conscription was introduced and I would have been called up with the first or second batch of “Belisha Boys”.

I had enlisted with 254 Battery Royal Artillery and I discovered, it was quite good so far as Territorial Army units were concerned, for that summer it came fourth in Gt Britain in the “Kings Prize” competition for artillery at Larkhill, Salisbury. In fact I happened to be on holiday in the Isle of Wight at the time and made special arrangements to travel to Larkhill and join my unit for the final and if my memory serves me correctly the winner was a medium battery from Liverpool.

My job as a “specialist” was very interesting indeed because even though a humble gunner — the equivalent of a private in the infantry — I had to learn all about the theory of gunnery. However after a year or so, indeed after the first years camp I realised that I was not really cut out to be a military type. In fact I am in no doubt that the British in general are not military minded and are somewhat reluctant to dress up in uniform. However I found that many of those who were military minded and lovers of “spit and polish” were marked out for promotion but were not necessarily the best choices for other reasons. There was also I suppose a quite natural tendency to select tall or well built men for initial promotion but my later experience tended to show that courage and leadership find strange homes and sometimes it was a quiet or an inoffensive man who turned out to be the hero.

Well the pressure from Hitler’s Germany intensified. There was a partial mobilisation in 1938 and in the summer of that year we went to camp inland from Seaford, Sussex. There were no firing ranges there so the gunners could only go through the motions of being in action but the rest of us, signallers, drivers, specialists etc. put in plenty of practice and the weather was warm and sunny.

During 1939 our camp was held at Trawsfynydd and the weather was dreadful. It rained on and off over the whole fortnight. Our tents and marquees were blown away and we had to abandon our canvas homes and be reduced to living in doorless open stables. Despite the conditions we did a great deal of training which included an all night exercise. The odd thing that I never understood is that both in Territorial days and when training in England from the beginning of the war until we went abroad there was always a leaning towards rushing into action and taking up three or four positions in a morning’s outing yet when it came to the real thing we had all the time in the world and occupying a gun site was a slow and deliberate job undertaken with as much care as possible. I believe it was the same in the first World War and also at Waterloo so I can only assume that the authorities were intent on keeping us on the go rather than simulating actual wartime conditions. Apart from going out daily on to the firing ranges we had our moments of recreation and I took part in at least one football match against another battery but I cannot remember the result. I always played left back although I really was not heavy enough for that position but I was able to get by as a result of being able to run faster than most of the attacking forwards that I came up against.

The really odd coincidence was that our summer camp in Wales was an exact repetition of what happened in 1914. Another incident that is still quite clear in my memory was that at our Regimental Dinner held, I believe in late July or early August of 1939, Major General Liardet, our guest of honour, stated that we were likely to be at war with Germany within the following month. He was not far out in his timing!

Well the situation steadily worsened and the armed forces were again alerted. This time on the 25th August 1939 to be precise. I was “called up” or “embodied” along with about half a dozen others. I was at work that day at the office when I received a telephone call from my mother with the news that a telegram had been sent to me with orders to report to the Drill Hall at Shepherds Bush at once. This I had expected for some days as already more than half the young men in the office had already departed because they were in various anti-aircraft or searchlight units that had been put on a full war footing. So that morning I cleared my desk, said farewell to the older and more senior members who remained, went home, changed into uniform, picked up my kitbag that was already packed, caught the necessary bus and duly reported as ordered.

I was one of several “key personnel” detailed to man the reception tables in the drill hall, fill in the necessary documents for each individual soldier when the bulk of the battery arrived and be the general clerical dogsbodies, for which we received no thanks whatsoever. The remainder of the battery personnel trickled in during the following seven days up to September 2nd and after being vetted was sent on to billets at Hampstead whilst we remained at the “Bush”.

The other three batteries in the regiment, namely 253, 255 and 256 were mustered in exactly the same manner. For instance 256 Battery went from their drill hall to Edgware in motor coaches and were billeted in private houses. The duty signallers post was in the Police Station and when off duty they slept in the cells! Slit trenches were dug in the local playing fields and four hour passes were issued occasionally. There were two ATS attached to 256 Battery at that time a corporal cook, and her daughter who was the Battery Office typist.

I well remember the day Great Britain formally declared war on Germany, a Sunday, because one of the newspapers bore headlines something like “There will be no war”. Thereafter I always took with a pinch of salt anything I read in other newssheets.

At this time our regiment was armed with elderly 18 pounders and possibly even older (1916 I believe) 4.5 howitzers. My battery had howitzers. They were quite serviceable but totally out of date particularly when compared with the latest German guns. They had a low muzzle velocity and a maximum range of only 5600 yards. Our small arms were Short Lee Enfield rifles, also out of date and we had no automatics. There were not enough greatcoats to go round and the new recruits were issued with navy blue civilian coats. Our transport, when eventually some was provided, was a mixture of civilian and military vehicles.

Those of us who remained at the Drill Hall were under a loose kind of military discipline and I do not think it ever entered our heads that the war would last so long. I can remember considering the vastness of the British and French empires and thinking that Hitler was crazy to arouse the hostility of such mighty forces. Each day we mounted a guard on the empty building we occupied and each day a small squad marched round the back streets, which I am certain did nothing to raise the morale of the civilian population.

There were false air raid alarms and we spent quite a lot of time filling sandbags which were stacked up outside all the windows and doors to provide a protection against blast from exploding bombs. In the streets cars rushed around with their windscreens decorated with such notices as “DOCTOR”, “FIRST AID”, “PRIORITY” etc, and it was all so unnecessary. Sometimes I felt more like a member of a senior Boy Scout troop than a soldier in the British Army.

After a few weeks the rearguard as we were now called left the drill hall and moved to Hampstead, not far from the Underground station and where the remainder of the battery was billeted in civilian apartments. They were very reasonable except that somebody at regiment had the unreasonable idea of sounding reveille at 0530 and we all had to mill about in the dark because the whole country was blacked out and shaving in such conditions with cold water was not easy. Being a Lance Bombardier my job when on guard duty was to post the sentries at two hourly intervals but the problem was that as we had no guardhouse the sentries slept in their own beds and there was a fair number of new recruits. Therefore you can imagine that as there were still civilians present, occasionally the wrong man was called. I remember finding my way into a third or fourth floor room and shaking a man in bed whom I thought was the next sentry to go on duty only to be somewhat startled when he shot up in bed and shouted “go away this is the third time I have been woken up tonight and I have to go to work in a few hours time!”

Whilst we were at Hampstead leave was frequent in the evenings and at weekends. Training such as it was, was of a theoretical rather than a practical form. However we very soon moved to “Bifrons House” in Kent, an empty stately home in very large grounds near Bridge and about four miles south of Canterbury. Here we resided until the middle of 1940.

In this position we had a bugler who blew reveille every morning while the Union Jack was raised, and lights out at night. The food was quite appalling in my opinion. It was prepared in large vats by a large and grimy cook and by the time it was distributed was almost cold due to the unheated condition of the dining area. Breakfast usually consisted of eggs eaten in the cold semi darkness and the yolks had what appeared to be a kind of plastic skin on them that was almost unbreakable. Indeed all meals were of the same poor standard and there was no noticeable improvement during our stay here.

The winter of 1939/40 was very long, very cold and brought a heavy fall of snow which stayed with us for several weeks. Christmas day was unforgettable. I had a touch of ‘flu and the first aid post where another soldier and myself were sent to was an empty room in a lodge house. There was not a stick of furniture, no heating, the floors were bare and we slept on straw palliasses on the floor. I recovered very quickly and was out in two or three days! On one day of our stay at Bifrons, on a Saturday morning there was a Colonels inspection and as a large number of sergeants and bombardiers were absent from among the gun crews I was detailed to take charge of one gun and stand in the frozen snow for the best part of an hour on what was I believe the coldest day of the winter. And so far as I remember our Commanding Officer decided not to include us and eventually we were dismissed and thawed out around the nearest fire.

In general however I think most of us quite enjoyed our stay here. It certainly was not like home but we made ourselves comfortable and parades finished about 1630 hours which gave us a fair span of time until “lights out”. At weekends we spent the Saturday evening in the pub in nearby Bridge and occasionally walked or begged a lift to Canterbury which was four miles away. In our spare time we played chess and various games of cards. From time to time we were entertained by groups of visiting artists or had sing-songs in typical army fashion. Looking back it was in some ways I suppose like an of beat low class boarding school with the battery numbering some two hundred and fifty men billeted in the bedrooms and stables of the house. Nevertheless we did a lot of training. We even went out in the cold snow covered countryside at night in our vehicles as if we were advancing or retreating, for two or three hours at a time. We had to take a certain preselected route which was very difficult to follow because with everything hidden beneath the snow, with no signposts and with trying to read an inch to the mile map at night with a hand torch giving only a very restricted light because of the blackout the odds against making a mistake were fairly high. We would come back cold and hungry to a mug of hot tea or cocoa and a bite to eat. By day we practised other aspects of artillery warfare either as part of the battery as a whole, sometimes with our signallers but more often as not as a group of specialists going through the many things we had to learn, time after time. When the weather improved this was a most enjoyable way of spending the morning or afternoon session for we could take our instruments out to an attractive bit of the countryside within walking distance of our billets and do some survey, map reading or a command post exercise.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by saucyrita (BBC WW2 People's War)

Rita Savage (nee Atkinson)

A child’s view of the war.

In 1939 I was nine years old and living in Peckham, London S.E.15. It was 3rd September 1939 and I remember sitting on the back steps that led into the garden listening to my mum and dad discuss the advent of the Second World War. My parents had of course lived through the First World War. My dad served in the Army along with his brother and father; they were all in the same regiment I am told. My uncle Ernie was killed in France but my dad and my grandfather both survived.

This particular day as I sat on our back step, dad had switched on the wireless and we heard our then Prime Minister, Mr. Chamberlain broadcast that we were at war with Germany. A few minutes later we heard the distinctive wail of the air raid siren and I remember thinking that we were all going to die on this the first day of the war. All the tales I had been told about the First World War came back to me and I was terrified. My sister Doris would be about sixteen years of age then and she seemed to take it in her stride. My brother Brian was only about four years of age and too young to understand.

We didn’t have an air raid that day of course, the all clear sounded straightaway. We were simply being prepared for what was to come.

The first few weeks of the war went by and nothing significant happened that I was aware of except all the schools were closed in London where I lived anyway. I suppose all the teachers eligible were called up or they enlisted in our armed forces.

I got over my initial terror and enjoyed the freedom from school which I didn’t like very much anyway.

The next thing that happened was for me a very traumatic one — gas masks! I remember all the family going along to this large building, probably the Town Hall, I can’t remember now and waiting in a queue to be fitted for these horrible looking contraptions. My mother was very worried about my little brother Brian thinking that he would act up and cause a fuss. She didn’t worry about me; I was older and never made a fuss about anything.

Wrong! When it was my turn I did more than make a fuss, when they tried to put the mask over my face I remember becoming hysterical. I couldn’t bear to have my face covered; I have been like this all my life. Claustrophobia is the word of course but I didn’t know that at the time. My brother on the other hand wouldn’t take his off he wanted to keep it on. We were supposed to practice wearing these masks on a regular basis and I would always disappear and go into hiding.

My parents decided to move house at that time, only into the next road. Later on in the war the house we had moved from was flattened taking with it the house next door where some of our friends lived. There were five children in that family and they along with their parents were all killed. The house we had moved into was never bombed and had we known it then of course we could have stayed there throughout the war and gone to our beds to sleep every night and not to the Anderson shelter in the back garden.

The war had been going for about a year by this time with no air raids and the schools were beginning to open their doors once more when the blitz on London started in earnest.

That first air raid was a daytime one, I remember I was playing on the front with my friend and when I heard the siren I immediately ran to my mother who at the time was talking to someone at our front door. She hadn’t heard the siren at first and she was very cross with me for interrupting her, children were indeed seen and not heard in those days. I was forgiven however once my mother realised what was happening. We only just made it to the Anderson in time before we heard the enemy planes overhead and the bombs dropping all around us. My mother was in a state because my sister and my dad were at work. My dad and sister were all right thank goodness but they were both very shaken when they eventually arrived home.

That night the raids started in earnest. We spent every night after that in the Anderson shelter or as I will tell you later in other shelters. We would lie awake at night listening to the noise of the falling bombs and the noise of our ack ack guns and wonder if our house would still be standing in the morning.

My brother and I would lay either side of our mother and cover her ears with our hands. My mother was a complete nervous wreck after a few weeks of this bombardment of our city.

In retrospect I realise she was so afraid for us her children. In later years when I had my own children I would think back to these terrible times and only guess at her agony of mind and her fear for us her three children.

One day the lady next door said they were going away for a little while and as their shelter was a bit more comfortable than ours we could use it if we wanted to. So that evening off we all went with all the paraphernalia that was needed to take down the shelter with us, i.e. flasks of hot drinks, candles, matches, a torch etc, not forgetting the gas masks of course, making our way into next door’s garden and their shelter. When the door was closed we were completely sealed in and it was padded out so the noise wasn’t so horrendous. When we were settled later on and it was time to try to get some sleep dad blew out the candles. Fortunately for us my brother started to cry and complained of tummy ache so dad tried to re-light the candles but they just wouldn’t light. It was a few seconds before my dad realized they wouldn’t light because there was no air coming into the shelter. We got out of there pretty quickly and made our way back to our own shelter. But for Brian, my little brother, we could have all suffocated.

We next tried the cinema at the end of our road — I remember it was called “The Tower” — they had cellars underneath that were opened to the public at night to use as a shelter. We had quite a job to get somewhere to sit. They had these wooden benches covering the floor space and mum tried to make up beds for us children underneath these benches on the floor. We didn’t hear the noise so much but to my mother’s disgust a few of the older men sitting nearby every so often would spit on the floor quite close to where we lay. We were only there one night my mum wouldn’t go back again.

The next night mum dragged us all to the underground railway, the Oval at Kennington, the trains were not running at night and people made up their beds on the platforms. We thought we were early but when we got down there we had to step over bodies trying to find somewhere for ourselves. We had to give up as there was no room and we went back to our own shelter again. We heard later on that just after we had left the Oval a bomb was dropped at the entrance. Our guardian angel must have been watching over us that night.

My parents decided that we children should be evacuated as so many of the children were. Mum sewed our names in all our clothes and off we went to the railway station, I can’t remember which one it was, probably Euston, where daily trains would come in and children were packed in, gas masks around their necks, saying their goodbyes to parents left standing on the platforms. At the last minute mum couldn’t let us go — what a decision for a parent to have to make, not knowing where your child was going and if they would be treated well and looked after properly. This was probably just as well since my mum wanted my older sister to go too in order to keep an eye on us. This would not have worked of course for one she was seventeen and for another when the children got to their destination families were more often than not split up. My mum didn’t know this at the time though. So once again we all went back home.

I remember one morning in particular, we hadn’t been up from the shelter for long from the night before and the wail of the siren started up again. My mum and dad sent us children straight back to the shelter. Incidentally we had a dog called Trixie and as soon as she heard the siren she would make straight for the shelter, she was always in first. Anyway, the raid started almost before the siren had ended and bombs were dropping about us and our sister and parents were trapped in the house, they dived under the kitchen table for some protection. We children and our dog clung together praying that the rest of our family would be safe in the house but we both thought that they would surely die.

By this time my mother was so distraught she begged my father to give up his job so we could all move away from London together as a family. We had endured months of these terrible raids. My father was a milkman with the United Dairies and he would come home from work in a terrible state, collapsing into a chair and burying his face in his hands and really cry, at the same time trying to tell us how he had gone to deliver milk to his customers in the East end of London only to find whole streets wiped out and people he had known for years, laughed with, had cups of tea with, were all killed or made homeless their houses just smouldering rubble.

One night Brian had a very high temperature, he was prone to fits when he was a young child, my mum wouldn’t leave the house for the shelter in case it did him some harm so we all huddled under the stairs for some protection.

Later on that night the air raid warden knocked on all the doors in our road informing us that we had to get out of our homes because it was believed a land mine had been dropped at the end of our road. Mum would not leave, she said that if our number was up, so be it. She was not going to take Brian outside. Fortunately for us it turned out not to be a land mine after all just an unexploded bomb which was eventually defused by the bomb squad.

After this my dad did not need any persuading to leave London, he was ready to go. But where to! My sister Doris had a boyfriend called Ron who had been deferred from the armed forces because he was an electrician and had been sent by his firm to Stoke-on-Trent where he was engaged in electrical work at a munitions factory. He got us rooms in a house in Boughey Road, Shelton where he was also lodging.

The day we actually left our home in London is one I shall never forget because of the trauma and upheaval this move caused us. My mother had a boarder called John living with us and I remember him very clearly. He was always very kind to us children. He was a pharmacist and we thought of him as an adoptive uncle. He promised to take care of our dog and all our belongings until we could send for them. We also had a cat called Tibby and we all loved her very much but she was old and no one else wanted her so we had to say goodbye and sadly dad took her to be put to sleep. We also had a rabbit, pure white she was and so sweet. What a wrench to have to part with her as well, particularly for Brian who was only six at the time and he thought the world of her. We gave the rabbit away to friends who promised faithfully to look after her.

We packed everything we could carry of course and we were finally ready to go. All our neighbours came out to say goodbye and wish us luck with promises to keep an eye on our house and especially the dog. When I think back now, what wonderful neighbours they were, later on in my story they all rallied round and helped John with the removal of our furniture and belongings including Trixie, our dog. Anyway we eventually left and caught a bus taking us to Euston Station to catch the train for Stoke-on-Trent. As the bus moved slowly along Peckham High Street we heard the wail of the siren and the drone overhead of enemy aircraft. All of a sudden we heard an explosion and everything seemed to shake; we later heard that a bomb had been dropped not far behind us, if this had happened a few minutes earlier we would probably have been killed.

We arrived at Euston Station shaken but all in one piece and stood on the platform with our suitcases around our feet waiting for the train to take us out of the misery of living in wartime London which was once our home. The train was late and when it did arrive it was packed mostly with service men. We had to sit on our cases in the corridor of the train and we moved very slowly forward out of London and towards the Midlands. It was a terrible journey, the train kept stopping for no reason that we could see. It seemed to us children that we were on that train for hours. We finally arrived very tired and despondent and set foot for the first time on Stoke Station. We were met by Ron, Doris’s boyfriend. It’s such a long time ago now over sixty years, I cannot remember how we got from the station to Boughey Road, perhaps we walked. Anyway we arrived eventually and found that our landlady was very nice and very welcoming. We had the front bedroom upstairs, it contained a double bed which Brian and I shared with mum and dad and a camp bed at the foot of the double bed for Doris. We were okay with this arrangement since we had all been cramped together in the shelter in London. It was wonderful to be able to go to bed and go to sleep, what bliss! We did of course hear the siren some nights but we ignored it and stayed in bed, after what we had experienced the raids here were mild. There had been bombs dropped here locally before we arrived. The Royal Infirmary was hit and also a house in Richmond Street, Hartshill, I think it was Richmond Street anyway.

My mother, after a lot of tramping about in the Potteries, finally found a house in Princes Road, Hartshill which had not been lived in for ten years. In those days houses were all rented, no one bought a house, unless you were well off anyway. My poor mother had to scrub that house several times before we could move into it because of all the grime that had accumulated over the years. We had no choice really, we had to have this house, no other landlord would rent to us because we were from London and it was believed that Londoners did not stay long in the Potteries it was too quiet for them! Everything was so hard to get in wartime, when we moved in we had no electric or gas, we had to use candles for light and in the kitchen was a black leaded fireplace with an oven at the side which mum had to use until we could get a cooker. We did get an electric cooker eventually but if it had not been for Ron, who also came to live with us, we would not have been able to use it because the electricity board had no one they could send to install it. Ron fixed all our electricity problems, we were very lucky. Getting coal to heat such a large house was a very big problem, we burnt anything we could on that fire and in the evenings we all sat huddled together round it. We couldn’t get curtain material so we had to have black paper up at all the window because of the blackout.

The day when the removal van with all our furniture and best of all our dog eventually arrived was wonderful. The removal man wanted to buy Trixie from us he couldn’t get over how good she had been on the journey, never attempting to run away. She knew he was bringing her to us because she was with all our furniture and belongings in the van. We never went back to London after the war but made our home permanently in Stoke-on-Trent.

I would like to say to all those people in London and other towns who were so cruelly bombed how much I admire them for sticking it out. They were a lot braver than we were.

Written by Rita on 4 December 2003

Contributed originally by Bob Staten (BBC WW2 People's War)

When my son asked me if I should like to take part in this exercise, I said flippantly that my war could be summed up in two words, drink and promiscuity! However, it seemed to be a worthwhile project as so much of war does happen off-stage. I shall do my best to stick to the facts. Unfortunately, I have no records except a few old photographs.

During the 20’s and 30’s my friends and I mostly played at ‘War’ and it was always against the Germans. This is understandable because the First World War was fresh in people’s minds. Every house had its photographs, mementoes and stories of lost husbands, sons and relatives. The impressive one-minute’s silence on the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month is still with me. Walking with my father at Marble Arch and seeing the traffic halt and everyone standing by their vehicles with heads bowed was awe-inspiring to a young boy, and the silence so complete, on Remembrance Day.

I lived at 10, Capland House, Frampton Street, St. Marylebone, and my two friends ‘Pussy’ Hanlon and ‘Bimbo’ Jenner lived at flats 9 and 6. We often sat on the staircase and discussed which of the services we would join when war came. We assumed, quite naturally, that it would be against the Germans. In 1937, I joined the Royal Fusilier Cadets at Pond Street Drill Hall, Hampstead and learned how to drill and to use a rifle. We had .303 Lea Enfields and our own rifle range. There were trips to Shorncliffe Barracks, parades at the Fusilier memorial in Holborn and once, we took part in the inter-cadet shooting competition at Bisley. Because I liked the look of the red bandsmen’s uniform, I transferred to the band and became a bugle boy. In the summer of ’37, we went to Belgium as guests of the army. Every evening we ‘beat the retreat’ on the promenade in Ostend, which was appreciated by the holidaymakers. In the barracks, we also discovered that ‘Verboten Ingang’ means ‘Forbidden Entry’! When we visited the Menin gate, I played the ‘last Post’. This was a moving experience, especially after visiting the battlefields and extensive war-grave cemeteries with their endless crosses. The older men related their experiences to us, which made it all very real. We little thought that Belgium was soon to be overrun by the Germans once again.

I was sixteen when the war broke out, working as a motorcycle messenger boy, hoping to become a GPO telephone engineer. When it was formed, I left the cadets and joined the Local Defence Volunteers (LDV), which eventually became the Home Guard. We wore our own civilian clothes with LDV armbands. One of our tasks was to guard the Telephone Exchange in Maida Vale. We had a variety of weapons and two or three rifles with little ammunition. I remember being on duty from midnight to 0200 hours when I was supposed to wake up the next man. He looked so old and frail that I was too shy to wake him up. The sergeant was not pleased to find me standing there in the early hours of the morning. We fully expected German parachutists to descend upon us in a variety of cunning disguises. They would not fool us because we would be able to see their jackboots! I think we were quite disappointed when nothing happened!

At home, we were busy filing sandbags to protect the fronts of our flats, sticking tape on the windows and making blackout curtains. We were issued with gas masks, which we practised putting on very quickly and sometimes walked around in them to get used to it. My two older brothers, Arthur and Bill joined the LDV and RAF respectively, Arthur to become a sergeant in the Home Guard and Bill a wireless operator/ air gunner. As I had to wait until I was 17 ½ before I could volunteer for the RAF Volunteer Reserve, I transferred to the Air Training Corps.Our Commanding Officer was an old Royal Artillery gunner who gave us lectures on spotting artillery positions from a tethered balloon that he remembered from the First World War. We had instruction in air-navigation, signalling and meteorology and spent a great deal of time over smartness and drill. One day we were visited by Claude Graham-White, the famous air pioneer, who lived locally. I was asked to welcome him by playing the ‘General salute’ on my bugle. He gave a most interesting talk about his air bombing experiments at Hendon before the First World War. He told us that he had marked out the shape of a full sized battleship in chalk on the ground, flown over it and dropped bags of flour. This was to show how aeroplanes would change the shape of war in the future. He was rather bitter because he said that the ‘brass-hats’ did not fully understand the significance of what he was so graphically demonstrating to them. Whilst in the ATC, I visited RAF Manston during the ‘phoney war’, when everyone seemed to be waiting for something to happen. They had a squadron of Hurricanes, a squadron of Blenheim Mk 1s, being used as fighters with four Browning machine guns fixed under the fuselage, and a squadron of Wellingtons, which were being used as magnetic-mine detectors. These looked extremely odd with large circular white electro-magnets completely encircling the underside of the aircraft. My ATC squadron was also engaged in helping a balloon barrage unit whose headquarters were in Winfield House, Regent’s Park. This was a grand palatial mansion which had belonged to Barbara Hutton, the Woolworth heiress. The two sections with which I was involved were at Primrose Hill and Lord’s Cricket Ground. We mostly did guard duty but in rough weather and high winds, we sometimes manned the mooring ropes.

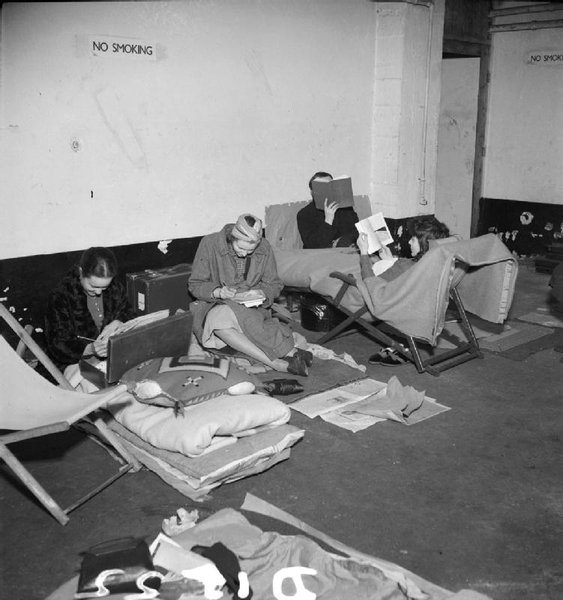

During the ‘phoney war’, air-raid shelters were being completed and were in place before the first air raids. These, once they started, became part of our lives and were so regular we knew when to expect them. We made our own fun, took out thermos flasks, sandwiches and blankets ready for a long stay down in the shelter. We had an old wind-up gramophone and a few records. The most popular were ‘In the Mood’ and ‘Begin the Beguine’. Quite often, we had a singsong with ‘Roll Out The barrel’, ‘Run Rabbit Run’, and many of the First World War favourites like ‘Pack up Your Troubles’. The older men seemed to relive the comradeship that they had known when they were in the trenches. My dad was always ready for the sirens with his shopping bag of food and drink and a pocketful of half-pennies to play his favourite game of ‘Ha’penny Brag’. In fact, he got quite impatient for the air raid to begin so that he could get settled in the shelter with his mates. ‘They’re late tonight son!’ was his regular critical comment of the enemy’s laxity.

We had two bombs on Frampton Street, one on a communal shelter next to the ‘Duke of Clarence’ and another on a block of flats next to ‘The Phoenix’. Many neighbours were killed. I particularly remember the ‘Clarence’ bomb. We heard it coming like an express train louder and louder seemingly meant for us, then a great flash and explosion, shaking and reverberations, then silence as if everyone was catching their breath. Then loud cries and screams. We were very shaken and shocked but blinded by choking smoke and dust and could taste dirt in our mouths. We had two stirrup pumps and put out some subsidiary fires in the street nearby. There were so many people helping or staggering about that the older men told us to keep out of the way. Another bomb fell, in daylight, at the junction of Luton Street and Penfold Street leaving a large crater. A local woman was injured and had to have her leg amputated below the knee. On another night, Mr Overhead, a friend of the family, was killed in his house in Orchardson Street near the fish and chip shop. During a very bad raid, we heard that Mann Egerton’s garage was ablaze so some of us went and pushed or drove out as many cars as we could and parked them in and around Church Street.

I volunteered for the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve just before my 18th birthday (January 1941) at a recruiting centre off Euston Rd. Later, I had to go for various physical and aptitude tests. These took place at Euston House. Eventually, I received a letter confirming my acceptance for aircrew training enclosing a small silver RAF badge, which I wore proudly in my lapel. I continued with my ATC training and was made up to sergeant. It seemed ages but one day a letter arrived telling me to report to No 1 Air Crew Receiving Centre (ACRC) at Lord’s Cricket Ground on 3rd September 1941. This was just around the corner from my home and was nicked named ‘Arsey-Tarsey’! My dad’s advice as I left the house was ‘take care of your boots!’ This was because on his first day in the Royal West Kent regiment (The Buffs), someone had stolen his boots and he had never forgotten it.

When I arrived at the ground, I sat in the Mound Stand, which was marked alphabetically, and listened, with the other recruits to my first roll call. From Lord’s we marched to large blocks of luxury flats in Prince Albert Rd overlooking Regent’s park Canal. One of our first tasks was to take our oaths of loyalty to the King and to be given our official numbers, which we were told to memorise. On the second day, we marched to a large garage in Park Rd where we were kitted out. When we got back to our billets, we had great fun trying on our uniforms especially the long woollen underwear in which we sparred with each other like old time boxers. We were very proud when we walked out for the first time in our ‘best blue’ wearing the white flashes on our caps, which denoted that we were aircrew trainees. Whilst at Regent’s Park we used the Zoo restaurant for meals. As we queued up the monkeys greeted us with loud screeches and whoops, which we of course imitated to get them even more excited. Our time was mostly spent in drilling and learning about RAF regulations and expectations. We did some signalling with an Aldis Lamp and were introduced to Morse Code, which I fortunately had learned in the ATC. Aircraft recognition was given in Rudolph Steiner House in Park St. Some of us who needed it were given a crash course in mathematics, with particular attention to trigonometry. After 4 - 5 weeks, we were posted to Initial Training Wing (ITW) Torquay.When we arrived, my particular group were billeted in ‘Rosetor’ Hotel. Thus began a very vigorous and demanding programme of activities. Up very early jogging along the front, lots of physical training, marching, rifle drill until we were extremely fit and smart. We were given lessons in air navigation at Tor Abbey, signalling by buzzer and lamp, airmanship, aircraft recognition, gas drill, King’s regulations, administration and more mathematics. One day, we had to march in full kit with rifles about 10 miles inland to a small hamlet. We were told that this would be our line of defence if there were an invasion. When we had finished the course we ceased to be ACII’s (AC Plonks) and became Leading Aircraftsmen (LAC’s ) which entitled us to wear the propeller insignia on our sleeves.

From Torquay, we were posted to RAF Booker, near High Wycombe to be assessed as to our suitability for pilot training. The aircraft were Tiger Moths with open cockpits. We were taken up for air experience initially, but it wasn’t long before we were being thrown about the sky in a whole series of aerobatics to see if we could cope. After two or three weeks, we were posted to Heaton Park, Manchester prior to going overseas.

At Heaton Park we were billeted in private houses and had to report to the park for roll call every morning. We had one or two ‘pep-talks’ in the local cinema. One of these, I remember was by Godfrey Winn, the writer and broadcaster. After a couple of weeks, we were divided into groups destined to be trained in the USA, Canada or South Africa, which were all part of the Empire Training Scheme. We were not told of our destinations except for having to mark a code word on our kit bags. After embarkation leave, my group entrained for Greenock, Scotland where we boarded an American ship — ‘The George F. Elliott’. We were shown to our sleeping quarters, which were well below the water line, where we were packed suffocatingly into an area filled with five-tier bunks. I had a top bunk and could quite easily touch the men on either side and at my head and feet. I also had a hot pipe just above me on which I frequently burnt myself. Soon after embarking, we left the River Clyde and joined a straggle of ships. The Royal Navy gently shepherded us into some semblance of order and although they seemed to fuss and hoot around, gave us a great deal of confidence. This was greatly needed because the night before we had a religious service when we sung the hymn ‘For Those in Peril on the Sea' and we knew that this referred to us and our journey.

End of Part One

Contributed originally by Herts Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

Hello. My name is Alan French, and today is the 14th October 2004. The anniversary of the battle of Hastings. Well firstly I can’t remember a lot about World War Two, because I was wearing napkins at the time. My war time experiences were spent in Abbot’s Langley and Holloway.(Not the famous part, but the region in London.)I have got a feint memory of my father being close to my face going, 'Shhh! Shhh!' and hearing some bangs in the background, which I think could have been bombs. I can also remember some blue curtains behind him. I’ve been told there was a situation where I was having a tin bath, because in those days we didn’t have bathrooms, unless you were terribly posh or very lucky. There was an explosion somewhere, and my father grabbed me out of the bath. When he looked, there were all bits of glass that had shattered in the water. So I was very lucky. Very lucky indeed. My mother had a sister, Mary. She also had a brother, George Beales. Her sister married into a family called Bishop, elsewhere in North London. The Bishops moved to Abbots Langley in the late 1930s. During the war, for a few months, my mother and I, stayed with them, in Breakspear Road. So that is why I hovered between Holloway, where I lived, and Abbots Langley during this conflict. Tom and Mary Bishop, with my cousins, had two dogs. Bob and Toby. Bob, I have been told would guard my pram. He would not let people near me. (Although, of course it could be that he was comfortable and did not wish to be interupted.)It was during my stay in Abbots Langley, that one of my older cousins, whilst in the army at the time, was married. Although some of my earliest recollections, probably took place in the war they are not all war related. One thing I can remember very distinctly, and it’s something that I’ve seen even in adult life, is that you didn’t have to go far without seeing a bomb site. I mean, quite close to me, there was a whole school that had been blown up. Things like that were common place. It was also quite common in the street, for some years, to see people who were unfortunate to have limbs, or an eye, missing. I understand that I was born during an air raid. When, a few months later, I was taken to Abbots Langley, I gather there were nasty things coming down from the sky and exploding upon landing. I was just rushed into the van, car, lorry or whatever vehicle, and whisked off. So I consider myself to be very lucky to be alive. There are many who are not. And of course there are stories you hear from your parents, and there are some you don’t hear. When I sit back and think, I don’t really know much about the nitty-gritty details of what my father did and whether he saw things that he didn’t want to talk about. He wanted to join the Royal Air Force. He went up to enlist, and I gather they said, “You’re missing”.

Apparently someone with the same name was missing from duty. He worked for a leather firm in Somers Town, which is in another part of London which comes under St Pancras. If you think about it, leather was a very valuable commodity. Soldiers used/needed it for boots, straps for rifles etc. So he was required to do some work in this field. At least one lady gave my mother bitter comments due to my father not being at the front. My mother worked for a firm called Cossor's who manufactured wireless sets, as they were called then, radio today, also radar equipment. She did say that there was this bomb or rocket or something,that severely damaged the factory leaving this huge awsome crater. The firm was based at Highbury Corner. We lived in a road called Madras Place, which is a turning sandwiched in between, Liverpool Road and Holloway Road. Appropriately one entrance is opposite the Islington Library, so perhaps I should be recording this interview there.My parents became fire watchers. I cannot find it at the moment but I know I’ve got a Fire Watchers Handbook and other hand books, Battle of Britain, What to do if Hitler Invades, and if I come across them I will come down here some day and say, 'Look what I’ve got!' I have some memorabilia here, including a letter from the desert which I will read out later, because its very difficult to transpose. (See Part two.) I’ve got a photograph of me at some celebration. I don’t know whether its 1945 or 1946. Because there were a lot of Victory parties in 1946 as well.

Q. Do you know which one you are?

A. That’s me and the lady on the end is my mother, only just in sight. The only other person I know there, is a little girl, in the front row, called Wendy, who used to live next door. There’s another little girl I played with called Denise, who also lived nearby. But I do not think she is in the photo. I don’t know where it was taken. I think it was organized by some Canadians. I was forbidden to go to one victory party. Apparently I was too young. Babies not allowed. My mother wasn’t very happy. I didn’t know this until I was well into my adulthood. In compensation, the organiser gave my mother a toy for me. She explained that I never had it. She said, ‘Well it was one of these things you sometimes get in Christmas crackers made of metal, you press it and it clicks. I thought it was very dangerous for a baby, and what's more it was made in Japan!'

Remember, the Japanese part of the conflict, ended, for the first time ever, in nuclear warfare. Nazi Germany was also on the verge of an atom bomb. See the film, 'The Heroes of Telemark.' So World War 2 was in some ways a nuclear war.

Q. It must have been very difficult for your mum and dad to have had such a small baby.

A. Yes.From what I gather, they used to live in Westbourne Road, which is in the Barnsbury part of Islington. I think they were a little worried because they were living upstairs somewhere, and with bombs coming down, if anything happened... So they moved to Madras Place, in Islington's Holloway region. We lived downstairs. We had at least one bedroom, a kitchen, a living room and a front room. There were other people who lived above us. There was Mr & Mrs Horton. Above them, at the top, there was a man I called 'Uncle' Jack. There was a lady who lived with him for a while. I am not sure in what way she was related to him. Before he moved in, there was a Mrs Bennett who died. I can remember quite clearly other neighbours. I have already referred to Wendy, who together with her brother Trevor,lived next door with their parents, Ted and Doris. On the other side of my house,there was a family called Biggs, Mr. & Mrs. Wheeler and another lady called Alice, all living above or below one and other. Mr and Mrs Biggs, had a son who was in the Navy. Thanks to him, I had my first banana. He got it from Gibraltar. There might have been a daughter called Babs. I can remember elsewhere in the street, a family called Rowbottom. The block of flats at the junction of Liverpool Road and Madras Place, I can remember being built. I can't remember what was before them. Denise, to whom I have referred earlier, lived at the end of Ringcroft Street. One of two roads that entered Madras Place from its side. I can't remember her father's name, but her mother's name was Grace. There are stories I have heard. I don’t know whether or not I should tell them on the air, because they may not be for the squeamish, so If I do tell , there will have to be some toning down. There are some nasty stories and some very comical ones. Do you want to hear the serious ones first?

Yes, tell the serious ones.

OK, I’ll try and tone down the first one because it’s not very pleasant. I gather a bomb or rocket came down and exploded. A pub's bar room floor collapsed with people on it, into the cellar. Unfortunately, there were spirits in the cellar. They ignited. There was a huge mass panic to get people out. I’ve toned that story down considerably. Another tragic one, is where a rocket came down on a house and a woman, who incredibly, had thirteen children, happened to be out at the time. All thirteen children were killed. Just like that. I have been informed by someone, who claims that he went into the building afterwards. There was nothing that could be done. It was a terrible sight. The children were just all huddled there. All that could be done,was just get their bodies out. There was nothing else you could do. I have also heard of a woman's husband being absoloutely riddled with bullets. So there were some tragedies. But I’ve also heard that sometimes, there were were things that could make you laugh. There’s the situation of a Costermonger, (Costers as they were also called as well as barrow boys) named Billy Hutchings, who when I knew him had a stall on the Holloway Road Pavement Market, as did one of my grandmothers, Lucy Offer. (Offer, by her second marriage.) Unfortunately, whilst he was taking his bath, (A tin one) a rocket came over Islington and split in half. One half just went into a roof without exploding. I don’t know if it was his house or a house nearby. Inevitably, something came down the chimney - soot, dust etc all over him. There is a story I can tell of a similar experience someone had when I moved to Hemel Hempstead but it has nothing to do with the war.

End of Part One.

The second half includes the reading of a letter from Tunisia as well as a continuation of this interview.

By the same contributor:-

'The Three English Brothers French.'

'The White Figure.' (A true wartime ghost story.)

Contributed originally by Suffolk Family History Society (BBC WW2 People's War)

Of course, 'way back in the 1930's "teenagers" hadn't been invented. In those now far off days one remained a 'child' -dependent on, and obedient to one's parents for more years than is often the case now, and the age of 'Majority', supposed adulthood, was 21, when you got the 'key of the door'. So, in the early 1930's, having moved to Acton from Kensington, where I was born in the 1st floor flat of 236, Ladbroke Grove, I grew towards my 'teens, enjoying a secure and happy childhood, doing reasonably well at School (Haberdashers' Aske's Girls' School, Creffield Rd) making friends and with freedom to play outside, alone or with my friends, and with no thought of danger from strangers, or heavy traffic.

And so, in 1939, I was 13 years old, when the war began. We had been on holiday in Oban, Argyll, where I now live, and as the news became more and more grave, and teachers were called back to help to evacuate school children from London, and Army and Navy reservists were called up, we travelled by car across to Aberdeen on Saturday 1st Sept. After a night in the George Hotel, and thinking the Germans were already bombing us when a petrol garage caught fire and cans of petrol blew up one after another, we caught the 9am train to London, Euston. The car travelled as freight in a van at the rear of the train (no Motorail then). The train was packed with service personnel, civilians going to join up and other families returning from holiday.

All day we travelled South. On the journey, there were numerous unscheduled stops in the 'middle of nowhere', and a severe thunderstorm in the Midlands added to the tension. Our car, in its van was taken off the train at Crewe to make room for war cargo (as we learned later). In normal times, the journey in those days took 12 hours to London. With the storm, numerous delays, and diversions and shunting into sidings, it was destined to take 18 hours. As darkness fell, blackout blinds already fitted, were pulled down and the carriages were lit by eerie dim blue lights. Soldiers and airmen sprawled across their kitbags in the corridors as well as in the carriages, sleeping fitfully. Nobody talked much.

Midnight passed, 1am. At last around 2am, tired, anxious and dishevelled, we finally arrived at Euston station on the morning of Sunday September 3rd.

My Mother and I sat wearily by our luggage in the vast draughty booking hall while my Father went off to see if, or when the car might eventually arrive. There was no guarantee. There were no Underground trains running until 6am, and, it seemed, no taxis to be had. In the end we sat there in the station forecourt until my Father decided that he could rouse his brother to come and collect us and our luggage. And so we finally reached home, had a brief few hours' sleep and woke in time to hear Mr Chamberlain, the Prime Minister, make his historic 11am speech. Those who remember it all know the icy shock of those words, that - 'consequently we are now at war with Germany'.

The air-raid sirens sounded almost immediately, though it was apparently a false alarm, but my parents decided that we would go and live at our country 'bungalow' at Ashford, Middlesex. Ashford in those days was little more than a village. London airport was a small airfield called Heathrow.

The 'bungalow' was simply one large wooden-built room, set on brick pillars, and roofed with corrugated asbestos, painted green, with a balcony surrounded by a yellow and green railing. Three wooden steps led down into the garden. Two sash windows gave a view of our large 3 acre garden, curtained with floral -patterned chintz curtains. Inside at one end was a sink fed by a rainwater tank, and an electric cooker, a large table, chairs and a large cupboard for crockery. Normally, we had, pre-war, used it for summer evening or weekend visits, returning home at night. It was only a six mile journey along the Great West Road.

Now, though, with war declared hurried preparations were made to leave London, as my parents didn't know what might happen in the way of possible attack on the Capital. Several journeys were made by car with mattresses, bedding, food, extra utensils, clothes and animals (two cats and two tortoises). The cats roamed free, having previously been used to the garden when we went on holiday, when they were housed in the bungalow and fed and cared for by our part-time gardener. They loved the freedom and the tree-climbing and never went astray. The torties, though, had to be tethered by means of a cord through a hole drilled in the back flanged edge of the shell (this is no more painful than cutting one's nails) until a large secure pen could be made, and a shelter rigged up.

My Father's brother joined us, his wife and son having already left for safety, and to be near his son's school, already evacuated to near Crowthorne, Berks.

After sleeping on the mattresses on the floor for a few nights (all 4 or us in the one room, of course), bed frames were brought from home and a rail and a curtain rigged up to make 2 'rooms' for privacy at night. My Father and Uncle slept in a double bed, both being fairly portly (!) and my Mother and I shared a single bed, which was rather a tight squeeze. There was no room for 2 double beds, and I was fairly small. After a few nights my Mother decided that we would have more room if we slept 'top-to-tail' and so we did this.

The lavatory was about 10 yards along a side path, and had to be flushed with a bucket of water. We were lucky in that we also were able to tap a well of underground water, for which my Father had rigged-up a pump. So even if there had not been much rain to fill the house tank, we could always obtain pure water from the well. Later we were connected to the mains. The lavatory emptied into a cesspit which my Father had dug.

This was the period of the 'phoney' war. I was enrolled at Ashford County School, which I only attended for one term, as we returned home to Acton at Christmas.

My own school had been evacuated to Dorchester with about half its pupils. Many parents, like my own, had decided not to send their children away. Later, some of those who had been evacuated became very homesick and returned home. Soon the school in Acton re-opened, with many of the Mistresses who had also returned to London. The Dorchester girls shared a local school, with both sets of girls attending on a half day basis.

Ration books and clothing coupons, food shortages and tightened belts became the norm, as, at school, did gas-mask drills in which we donned our masks and worked in them for a short while to become used to them. They smelt dankly rubbery. However sometimes we had a bit of fun as they could emit snorting noises!

My Mother had lined curtains with yards and yards of blackout material, and our large sash windows were criss-crossed with sticky tape. A stirrup pump, bucket of water and bucket of sand stood handy in case of incendiary bombs. All through the war, wherever we lived, we each kept a small case ready packed with spare clothing, wash things, a torch, and any valuables.

Wherever we went we carried our gas mask in its cardboard case on a strap over our shoulder. We each wore an identity bracelet with name and identity number. Mine was BRBA 2183. Butter and bacon rationing began on Dec. 8th - 4 oz of each per person per week.

Contributed originally by Researcher 232765 (BBC WW2 People's War)

Working and travelling to London in the wars years was no picnic; more often that not air raids shut down the underground, so getting to and from work could mean hours of delay.

My father and sister worked for the LNER (London North Eastern Railway) in the King’s Cross Station offices on Cheney Road, which have since been demolished and replaced with a car park. To help with the problem of clearing the station in the event of an air raid a volunteer fire guard duty was organised by railway staff. The duty required that the guard spend hours on the station roof listening for sirens or watching for approaching aircraft: if an attack was imminent the fire guard sounded a siren to clear the building. (My father held the record for clearing the station the highest number of times.)

My sister Connie was a typist in the typing pool. She recalls that on one occasion word went round that the greengrocer at the bottom of the escalator at King’s Cross underground station had received a delivery of cherries, so she rushed off to join the queue, quite forgetting to take a bag to put them in. She decided to use her ‘tin hat’ as a carrier. On returning to ground level she realised that there was an air raid, so she hurried through the station to get to the office shelter.

Suddenly there was the sound of a V1 and just as suddenly the engine cut out. The next thing she knew a soldier knocked her to the ground and threw himself over her as protection from the blast. As luck would have it the buzz bomb landed just outside the station, causing a great deal of damage and loss of life. She said she would never forget the screams and panic of people trying to get out of the trains. When she finally got back to the office, father was waiting for her, asking where the hell she had been, and why she wasn’t wearing her tin hat. She showed him the tin hat with the cherries in it and he went mad!

Contributed originally by Haystack (BBC WW2 People's War)

CHANGE OF LIFE

Born 1933 I turned 6 ½ on 23rd August 1939. At that age memories are not meant to span a period of over 64 years and those that do are faint, but a handful of them live with one forever. Like the memory of a gang of schoolchildren in caps, scruffy scarves and what passed as School Uniform attempting to board a smoke-shrouded train at the end of a platform on what must have been Euston Station (just like those old black and white films of troops boarding trains to go to the front being seen off by their loved ones, but with the people involved being a generation younger).

Ironically Euston Station is situated less than a mile from where I had lived since birth in Phoenix Street. Phoenix Street borders the area known as Somers Town which infills the space between Euston’s platforms and the marshalling yards of St Pancras, and is where my father’s shop (a tobacconist and confectioner’s) was situated (as No 54, later to be redesignated 58 Phoenix Road). Our flat was situated right above the shop, in one of the blocks of ‘buildings’ which characterise the area, so I suppose we were considered first in line for Hitler’s bombs. I believe we must have been evacuated before war was actually declared – if not it was immediately after September 3rd – and I recall my mother, among the crowd seeing us off, being upset and telling me not to worry as I would not be away for long. Away where? As it transpired later that day even she could not know.