Bombs dropped in the ward of: Bishopsgate

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Bishopsgate:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 29

- Parachute Mine

- 3

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

No bombs were registered in this area

Memories in Bishopsgate

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by nigelquiney (BBC WW2 People's War)

By Nigel Quiney 2003

Having become attuned to the sound, appearance and behaviour of the doodlebugs in 1944, it came like a thunderbolt from the sky when the Germans then launched their jet-propelled rocket bombs later that year over London. There was no warning. You did not see them, and if you did hear them, you had probably had it!

Enough was enough. We had survived the blitz and regular bombing raids. We could put up with the doodlebugs which ponderously moved across the sky until their engines stopped but these V2 rockets which suddenly appeared from nowhere and exploded before you even knew it was coming, scared the hell out of everyone and the reaction was prompt. Oakfield School in West Dulwich where we lived offered an alternative country location from South London and parents were offered their choice. It was all decided with astonishing speed; the country school would be run by Kathleen Livingston, leaving her husband David, the head-master, to look after the original in Dulwich for those whose parents did not wish their children to go. So in January 1945, my brother Tony and I were evacuated from London.

For me the ensuing experience was my first taste of real horror. The war was a perfectly normal everyday thing as far as I was concerned, as were hardships, shortages and rationing. This was the only life I knew and I was a very happy and contented little boy of six years of age, who was very secure in the love and affection bestowed upon him from every quarter. The absolutely last thing I would have wanted was to be taken away from my parents and home, no matter what the danger. But this is exactly what happened.

What a pathetic sight we must have been, that day on Liverpool Street station. We children were all so pale and thin and in the main wearing overlarge clothes handed down by mothers, from siblings and relatives. Not sure of exactly what was going on, I held firmly onto my mother’s hand and clutched my much worn and over-loved pale-blue teddy close to my chest. Children and grown-ups jostled each other, trying to avoid the porters pulling overloaded trolleys piled high with suitcases and large parcels tied with string as we walked along the platform past the waiting train looking for our carriage. Steam hissed through the clouds of belching sulphurous smoke as though a warning of things to come when I panicked and dropped poor teddy, who fell through the smoke and between the platform and the train and onto the railway tracks. It was as though I had dropped my own baby as my wail of horror rose above the general din on that terrible platform that fateful day.

Subconsciously, I must have known or even smelt my expulsion from the warmth of the family nest. Did I hurl teddy between the wheels of the train and the hard shiny steel of the rails as a cri de coeur, an agonised cry for attention to stop the impending nightmare? Maybe, but it did not change the ensuing course of events.

A kindly and sympathetic porter heard my cry and must have seen what happened and stepped forward to explain to my parents. He then crouched down by the edge of the platform and swung his legs by the side of the train until he was standing on the aggregate between the wooden sleepers. Carefully, he lowered himself until he was almost out of our view, as he scrabbled about under the train and then hesitantly and slowly he re-appeared until he was standing upright again and there in his outstretched hand was teddy. What a hero. A veritable champion.

We soon found our compartment and Tony and I and some other assorted older boys, accompanied by Kathleen Livingston from Oakfield School, were ushered into the train. By now, I was clutching teddy as though glued to my side and then we were off.

Slowly the great steel coal-burning monster hauled carriage- loads of vulnerable evacuees out of Liverpool Street Station and gathered speed for the perceived safety of rural Norfolk.

As the train chugged through the countryside that day, it began to dawn on me that the unthinkable was happening. We were being sent away from our family and home. I do not remember if my parents talked to me about what was going to happen. Probably not. I was only six years old and anyway how could I have understood. I would have screamed up a storm, so my guess is that my ten-year-old brother got the explanation and poor little chap, got the job of trying to explain and look after me, his very much younger brother. When you are ten years old, a younger brother of six is like comparing an eighteen year old to a twelve year old. What a bother, and what an embarrassment and what an annoying and unwanted responsibility. But I have to say looking back now, what else could my parents have done?

I do not remember the details of our journey except that we arrived in Norwich, changed trains and chugged back down the line and finally arrived at Eccles Hall somewhere in Norfolk. A beautiful two- storey sixteenth-century dower house facing east, behind which was Snetterton air force base housing the American 96 bomber group.

Not all the boys and girls were evacuated to Eccles Hall. My cousin Michael, for example, stayed on in London for some reason. In all though, about seven or eight small boys shared the junior dormitory and about twenty in the senior one. I was separated from my brother due to his four years of seniority.

Staffing was meagre. Kathleen Livingston was head mistress and also taught English. Miss Westall taught mathematics. She had been the original founder and owner of Oakfield School but had sold to David Livingston and had come out of retirement to help. Miss Wimbolt taught art, and something else which I can no longer remember. She was an extraordinary character. She only wore men’s dark, tailored double-breasted suits with all the accessories. Black brogues, shirt, with turn-back cuffs held together with plain gold cufflinks, and a silk tie. Her dark hair was cut short, and was worn with a side parting and to complete the picture she wore a monocle. She terrified me, not only because she looked like no other woman I had ever seen, but also because I thought that she resembled Hitler. Lawks-a-mercy!

Miss Cayley taught us nature studies and mainly looked after we six-year-olds. She was frail looking, fluffy and kind. I think! In truth I find it hard to picture her, so it must have been so. The villains are always easier to remember.

Which brings me to Florrie Johnson our matron and cook. A tall straight-backed woman of monstrous proportions. She had a big head with course mid-brown, lack-lustre hair pulled back into a heavy bun, small eyes and thick lips. She did not wear make-up. From her double chin down, she just grew and grew. Her shoulders were not that wide, but beneath grew mammoth breasts and from then on she appeared straight all the way down to the hem of her white matron’s cotton coat. Her sturdy thick legs were clad in brown woollen stockings and supported by sensible white nurse’s shoes. She had two children. A boy of about my age named Martin and his older sister Christine. Martin was blonde, slim and very pretty with a real peaches-and-cream complexion. Christine was blonde, fat and spotty.

Lastly came Ivy. She was Florrie Johnson’s little helper, and lived very much in the big woman’s shadow doing, I suspect, all the unpleasant jobs that were heaped upon her, for she was a poor mousy soul.

In the weeks preceding our evacuation, mother had lovingly put together a separate tuck box each for Tony and I. How she had gathered this collection of sweets, fruit, biscuits and cake for us I do not know. I am sure it meant that she and my father went without for weeks. She had also managed to provide some paper and coloured pencils which, along with our tuck boxes and suitcases containing our other few possessions stood along-side us as we waited together with the other pupils outside the imposing front of Eccles Hall.

We were segregated into sexes and then the boys were split up according to their age groups with Mrs Johnson taking charge. She explained that there would be no eating-matter of any description allowed in the dormitories and we were to hand over to her our tuck boxes for safekeeping. Then we were taken off in our groups to the relevant dormitory to unpack and settle in.

Of course, we never did see our tuck-boxes again. The explanation given was that all pupils’ tuck would be pooled and handed out in even proportions favouring nobody. Well, that did not happen. Mrs. Johnson, acting as custodian of the goodies, gave, I strongly suspect, two for every one sweet in favour of her family and in particular her children. We also got the least interesting and most ordinary from what was available. No wonder that Christine was so fat and spotty!

Tony and I felt thoroughly cheated, as did the other pupils. The subterfuge was so obvious and we all schemed that should further tuck come our way we would find places to hide it and not hand it over to Mrs Johnson.

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

Every Sunday we attended Eccles church, which was situated at the end of a lane just a short distance from our school. Close by the grounds at the back of Eccles Hall was Snetterton air force base, which was currently being used by the American 96th Bomber Command. Every so often we would see the occasional GI dressed so snazzily in their air-force gear and looking so handsome and strong it felt that they had come from another world. If they spotted us they would always welcome us with a wave and a smile. They almost became god-like in our eyes.

I remember well one morning after we had said our prayers in Eccles Church, sung hymns and fidgeted through the sermon, that upon leaving, a deeply touching event took place. As our straggly line of children walked down the lane back towards Eccles Hall we were suddenly aware of little piles of chocolate bars, sweets and packets of chewing gum lying in our path. The American GI’s had left them there for us, knowing that they would be enormous treats. Of course as soon as we realised that these goodies were meant for us, we scattered like hungry chickens at feeding time, to grab as much as possible. Those GI’s were so kind, it was as though they realised how homesick we were, but of course they too shared our feelings. It is heart wrenching to realise that some of them were only eighteen years old and thousands of miles from home. But over the whole time I was at Eccles, those GI’s were so kind and generous, but always in an anonymous way. They were never around for the thanks and gratitude. However, Mrs Johnson of course spoilt the event. As soon as calm was restored she ordered that all the goodies were to be handed in for redistribution at a later date. We all knew what that meant!

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

At the rear of Eccles Hall an additional wing had been built in the nineteenth century. This was to be used for the older boys dormitory, and would be where my brother would sleep, but I do not think I was ever allowed inside. My little gaggle of six and seven year olds was housed in a big bedroom at the rear of the original building and my bed immediately faced the door. Outside this door was a landing, with a passage running straight ahead, to the left of which was a big bathroom and at the very end, the lavatory. So began our stay at Eccles Hall.

I was incredibly homesick.

Our lessons in the junior section were simple but not unpleasant. Mostly, they were nature studies with illustrations and names of birds, animals and flowers. There was much to see within the grounds of Eccles Hall and particularly fascinating to me was the flock of peacocks, which nested there. Every so often their screeching reminded us of their presence. Being January it was extremely cold and there was not a lot of activity to see on our walks. The countryside was fairly flat, with the occasional pretty lane winding gently through it, bordered by hedgerow and with fields beyond. There were some copses of trees partly surrounded by wild unkempt bushes and shrubs, intertwined with rambling blackberry and dog roses and bits of honeysuckle and ‘old man’s beard’, all of which made for quite exciting exploration later on.

Kathleen Livingston helped further with our hand writing, spelling and reading. We also had lessons specifically for writing letters home to our parents. These were particularly interesting because most of us started to write in our different childlike ways, of our being so unhappy and could we please come home. However, these letters were clearly not acceptable to teacher and were promptly binned.

We were then instructed to write our letters by copying the text written on the blackboard by teacher! My mother kept these letters and after her death nearly fifty years later, I found them neatly held together by ribbon in a shoebox. Here is an example of what I wrote:-

Dear Mummy and Daddy,

I hope you are both quite well. We are all feeling

very happy this morning because the sun is shining

so brightly. The daffodils are coming out now and

we can see their lovely yellow trumpets. The bees

are on the golden pussy palm getting the sweet nectar

and brushing the yellow pollen on their backs. The

thrushes are singing now on the topmost boughs.

Their singing is sweet. We know a poem called ‘The

Song of the Thrush’.

My love and kisses,

From Nigel

What must they have thought? The spelling and punctuation were perfect and although I quite liked nature studies, were these the thoughts and writing of a six-year old sent away to boarding school? They must have seen through the message with grave misgivings. All the letters are similarly written. Perhaps the most poignant one though, was the first, sent just after we settled in. It reads:-

Dear Mummy and Daddy

We arrived safely at Eccles Hall.

I am quite happy with the children.

With love

From Nigel

Would you believe it? However, nothing could be done to change events and the rhythm of daily life settled in.

Apart from the terrible homesickness, I had problems with one of the regular meals. Every day the menu changed a bit but after a week, was repeated exactly as the week before. Absolutely fine, except for one thing. The food in the main was perfectly edible and some of it was truly delicious. I particularly remember Thursday’s supper and this became my day of downfall. For starters we had baked beans on toast, which I just loved and my plate was clean as a whistle. I think I was introduced to this classic treat at Eccles Hall. Perhaps the beans only came in big catering tins for I have no memory of them at home or indeed at Oakfield School in Dulwich. My downfall came with what followed as a dessert. This was called Bakewell tart and if made with the correct ingredients, was delicious. Sadly, this was wartime, and the necessary ingredients were not available. No doubt Mrs. Johnson or Ivy thought it would be a great treat. It was not!

Instead of finely ground almonds, egg yolks and sugar topped with lemon icing, nestling in a biscuit pastry, what did we get? Breadcrumbs soaked in water, which was heavily flavoured with artificial almond essence, together with a spoonful of powdered egg, poured into a pastry base and baked in the oven with jam on top. I just hated it, as the resulting pasty sticky desert saturated with almond essence had a strong chemical taste which almost withered my tongue but at Eccles Hall you ate everything, come what may.

I took a mouthful, chewed, swallowed and heaved. I swallowed again and managed to keep it down. I began to sweat. I complained to Ivy that I did not like it, but she had had her instructions from Mrs. Johnson. All food had to be eaten and nothing would be wasted. I had to eat it all and that was that. Then bedtime.

Later as I lay in bed with pale-blue teddy protecting my back and a brown monkey glove puppet named ‘Gibber’, a hand-me-down from my brother, clasped to my chest in a cuddle, I threw up. Poor Gibber! I vomited all over him as well as the bedclothes, and guess what was visible for Mrs. Johnson to inspect when she finally arrived on the scene? It was, of course, baked beans!

I was taken to the bathroom and thoroughly washed. Ivy changed the bed linen and I was back in bed and soundly asleep within seconds. The next day Mrs. Johnson advised me that baked beans would now be banned from my diet, as I was obviously allergic to them and the shortfall of food would be made up with an alternative. There was to be no argument and that was to be that.

Poor Gibber. He was boiled in the copper boiler along with the soiled bedclothes. He sort of survived but, my, he did age. His button eyes withdrew into his head and I felt very guilty. It was entirely my fault.

Then came the following Thursday and as decreed I was denied baked beans on toast. I protested strongly but to no avail. Then horror upon horror, I was given a double portion of Bakewell tart. I pleaded with Mrs. Johnson but now it was a battle of wills and she was determined to see that I ate every last crumb. So determined indeed that she stood over me watching in case I tried to secrete a spoonful or two and discard them under the table. Yet again I took a mouthful, chewed, swallowed and heaved. After the third I broke into a sweat. I pleaded with Mrs. Johnson that I felt sick.

“Nonsense,” she said. “You are just playing up because you aren’t fond of pudding and hope to get a double portion of baked beans. Eat it up immediately and I do not want any more of your whining.”

By now I had turned cold as I forced down this chemically flavoured sludge, and then the inevitable happened. I had turned round to beg her to let me stop, when I vomited with a projectile force and threw up on the boy sitting next to me, and all over Mrs. Johnson’s white cotton coat. I stood up terrified at what I had done, with my hands clutching at my mouth, when it happened again. This time sick spewed through my little fingers and onto the dining table. With a deep whimper and gulping sobs, I turned and fled from the room. Every eye was on me.

Luckily, Kathleen Livingston had seen everything and she followed Mrs. Johnson who was following me, so I was saved from matron’s obvious fury and God only knows what retribution which she was going to hand out. The ending to this story is that the following Thursday I was given a double portion of baked beans and I was allowed to go without the Bakewell tart. But Mrs. Johnson did not forgive me and I knew it. She bided her time for her revenge, but it did not come about for many weeks.

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

The weeks and weeks slipped slowly by towards spring and a new routine took over my life. It was not unpleasant except for my continuing desperate homesickness. However, by now I concluded that Mrs. Johnson was decidedly spooky. Take, for example, bedtime.

We juniors would gather upstairs in the dormitory and undress down to our vest and pants. We would then line up in the corridor outside the bathroom and those with the need would go to the lavatory. However, anyone taking longer than a couple of minutes was in danger of a worrying reaction from Mrs. Johnson. She would demand to know what we were doing and would bang on the door or worse push it open, usually just at the moment when one was leaning forward, bottom off the seat and about to wipe with a small piece of paper torn from a telephone directory. I do not know why this should be so embarrassing but it was. We all do it, but heaven knows what she thought we were doing in there.

At this point I must record a weekly episode, which took place every Sunday and was to do with “inner cleanliness”. I cannot remember the exact timing, but I suppose it must have been just after supper. Being a Sunday there was no homework and we finished our last snack of the day, something like bread and dripping, with a nice hot cup of tea. But it was tea made from Senna pods, which worked extremely efficiently and the end result was a rush upstairs to the toilets and a good and rapid emptying of the bowels. There were times on these Sundays when the supply of torn-up telephone directories ran dry.

Mrs. Johnson knew exactly how to make one feel vulnerable and control was the name of her game. It also did not help the business of emptying one’s bladder and bowels to feel that one was being timed. For the on-looking children, however, it was all very amusing until, of course, it was their own turn.

The bathroom was large and housed a huge tub in which would be a very meagre four to five inches of tepid water. Two boys would then get in the bath together and be soaped down, with Ivy helping Mrs. J. The water soon became rather grey and scummy but in truth we kids did not care and I think the original water was used for all us; eight youngsters per session. We were towelled dry and dressed in our pyjamas and then back to the dormitory where we were allowed about half an hour before lights off. The idea was, I suppose, for us to unwind gently and perhaps read a book.

No way. Kids will be kids and the biggest, strongest or eldest would usually start by hurling his pillow at a lesser and then trying to leap on the victim and in the ensuing struggle, remove his pyjama trousers. Once done, an attempt to hide the trousers added to the fun. What bullies these boys could be. Control freaks in the making.

I remember clearly one episode, after just such an event. My bed was located immediately opposite the dormitory door and because of this it was my job to keep cavey and warn of any possible surprises. Because it was winter and dark the landing was always well lit and the position of the overhead light would produce the shadow of anyone approaching our dormitory. This would be projected against the gap between the door and the floor. From my position in bed it was easy to see.

That evening the unmistakable shadow of Mrs. Johnson approached our door and I gesticulated wildly to advise of her presence, but the wrestling and de-bagging was so intent that my frantic waving was not noticed. I held my breath waiting for a cyclonic Mrs. Johnson to burst into our dormitory. Instead, however, the shadow became larger as though Mrs. J was crouching down to lean against the door.

She must have heard the noise of fighting and squeals of protest as pyjama bottoms were finally removed and the bully of the day leapt off his victim waving his booty. Then, I thought, is she peeping through the keyhole? Again the shadow changed shape and I knew that she now had her ear pressed to the door.

She stayed in that position for several minutes during which calm slowly descended on our dormitory. Pyjama bottoms were found and put back on and finally all the children were back in bed and between the sheets. As the quiet of impending sleep became obvious, the shadow shrank and re-formed into two segments representing her ankles. Mrs. Johnson was back on her feet. I then realised that our Mrs. Johnson not only liked eavesdropping but was a peeping tom as well. I suppose not so terrible really, but ...

A rather more worrying event took place towards the beginning of spring. At the rear of Eccles Hall was a large, well-kept lawn and on both sides were lines of fir trees. These were so large and thick that at the base they had almost joined up. This produced wonderful and exciting spaces for a child to explore and this is precisely what I was doing.

I imagined sheltering there, snug and protected from a violent thunder storm, or creating a hidden nest where I could share tuck with my imaginary friends Mrs. Yonksford’s lad and Mrs. Cronation’s lad who were still my constant companions. It was then that I found an incredibly beautiful feather. I carefully pulled it from the branches where it had been caught and studied it. It was over two feet long, and at the wide end shimmered blues and greens like the butterfly wings that were used in Victorian times under glass for decorative finishes. I held it gently against my side and continued exploring. Then I found another and a little further on, yet another. What a great find I thought, remembering those proud peacocks displaying their splendour. I then backed out of the dense foliage and onto the lawn clutching my three treasured feathers protectively.

“What have you got there?” boomed a voice, which I instantly recognised as belonging to Mrs. Johnson.

“Only some feathers, Mrs. Johnson,” I nervously replied. “I found them in the bushes.”

“That is nonsense, Nigel. I know what you have been up to,” she snapped. “You’re a very naughty boy, pulling feathers from those poor peacocks. Give them to me at once.”

She grabbed my arm and marched me off towards the house. We entered through the back door, climbed up the stairs and continued down a corridor until we reached the front landing.

“Stay here!” she commanded as she opened a door to one of the adjoining private rooms and shortly returned carrying a small wooden chair. This she placed directly in front of the big window centrally positioned over the main door.

“Now take off all your clothes Nigel,” she ordered, “and I mean all of them.”

I did as I had been told and at the same time protesting my innocence but she was having none of it. I folded up my clothes neatly and when I was stark naked she ordered me to stand on the chair in front of the window looking directly over the gravel drive.

“You are to stand upright, with your head held high looking straight ahead until I tell you to stop,” she said in her dictatorial tone.

I stood naked on that chair for about ten minutes, in full view of anyone below who might have looked up, before she relented and let me get down. If anyone had seen me up there, what on earth would they have thought? How would she have explained it all? So it was a punishment for pulling ‘armfuls’ of feathers from the peacocks tail. Big deal. Spooky?

In today’s language, Mrs. Johnson would have been considered a sick ticket!

As I have previously mentioned, bullying existed at Eccles Hall. This is not surprising. Bullying sadly exists everywhere in life and Eccles Hall was no exception. Luckily for me I was not a wimp, but I was one of the youngest and thankfully did have a knack for avoiding the worst of the bullies and their antics most of the time.

However, I was attacked by a rather rough, and older lad one day. I have no idea what started it all but the end result was a fight and my opponent suddenly produced a weapon in the form of a very sharp pencil. This he stabbed at my face, but mercifully a split second before hitting home, I wriggled and the pencil hit me just to the side of my left eye. The sharp lead end snapped off.

I screamed blue murder. Blood gushed, and I was now the centre of attraction. Kathleen Livingston arrived on the scene and I was rushed off to the bathroom. There, my wound was washed carefully and well cleaned with a good painting of tincture of iodine to ensure an antiseptic cleanliness and I screamed even louder as the iodine started to sting.

The wound healed with no problem but the pencil contained indelible lead and the end result was a blue line a quarter of an inch long, looking very much like a tattoo. I was rather proud of it and I have it to this day.

As I write this I remember that tradesmen used these pencils writing out invoices or receipts and many were in the habit of licking the lead point before writing. This produced a darker and permanent imprint on the paper and an amazing effect on their tongues but this was before ballpoint pens were invented which finally rang the death knell for indelible lead pencils. I wonder if their indelibly streaked tongues from 1945 are still marked to this day?

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

Sometime in March my brother Tony fell ill and it became clear that this was not just a bout of influenza. He was finally moved out of the senior dormitory and put into a small box room by himself. I was not particularly aware of this problem because the senior children did not really mix with us juniors, except for meal times and even then they sat together and separately from us.

Kathleen Livingston was obviously very concerned and ‘phoned my parents advising that she feared the possibility of my brother contracting infantile paralysis, nowadays known as polio. The medical profession had recently isolated this very serious disease and the dangers for young people were known. These were the days prior to anti-biotics being available and for serious illnesses we were given M&B tablets (these initials stood for the manufacturer, May & Baker). Such a puzzling name for a drug, by today’s way of thinking, when scientific-sounding brands are so common.

On hearing this worrying news, my parents made the journey to Eccles Hall. They arrived with one of my father’s cousins, named Eric, bearing a tuck box each for my brother and I. I was overjoyed to see them, literally throwing myself into my mother’s arms and sobbing with relief, somehow believing that they had come to take us back home. Wrong! Big disappointment, but it was wonderful for me to be with them, even for only a few days. We went on trips and even had a picnic on one of the warmer days. I was a very happy bunny. Tony was also clearly on the mend with the dangerous period of his illness over, so the time had come for them to catch the train back to London. I was allowed to see them off and Kathleen Livingston accompanied us to the little station of Eccles. As we waited for the train to arrive, the terrible ache of homesickness slowly spread through me and as the train pulled into the station I clung even more firmly to my mother’s neck.

Now, panic racked my small body as the train finally stopped and a few people stepped down onto the platform. Eric opened the door to a compartment and got onto the train. My mother was weeping as she tried to untangle my arms from around her neck and then I knew for certain that I was going to be left behind.

“No, please no!” I sobbed, burying my head against my mother’s shoulder, my tears streaming down my face and onto the collar of her jacket.

“Don’t go,” I pleaded, looking wildly around me for some saviour.

By now all three grown-ups were also in tears. The train blew its whistle and Kathleen Livingston gently put her arms around my waist and tried to pull me off my mother, but to no avail. I clung on for dear life with my arms still firmly around mother’s neck. At this point, poor father had to force my hands apart and loosening my grip, Kathleen was able to pull me away and into her arms. In no time Eric and my parents were in the carriage, the door shut behind them and with a great belching of smoke and hissing of steam, the train pulled slowly out of the station.

“Mummy, mummy!” I screamed wildly but they were gone.

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

What joy, what bliss, such happiness! Our first term at Eccles Hall had ended and we were going home for an Easter holiday at East Dean, a village in the South Downs a couple of miles from Eastbourne on the south coast. Tony had completely recovered from his illness and the news from the European front about the war was looking to be in our favour. We had had a wonderful time and people enjoyed an enormous sense of optimism highlighted by the fact that in August 1944 the beaches had been cleared of mines and were open to the public. Now, instead of just gazing down over the barbed wire towards the beckoning sea, we were able to cross over that forbidden line and explore. It was truly blissful.

I returned to Eccles Hall with a heavy heart but without the same fear and trepidation of the first journey. I think that by now I knew that my stay was not going to be for very long and that a few weeks or months would see the end of it for good. Certainly by summer we would be back again to beloved East Dean, and endless adventures.

I had by now been introduced to birds-nesting by Michael, my great East Dean chum. I have to say that today I am horrified by even the idea of finding a bird’s nest and stealing an egg or possibly two but Michael was very clear with his rules, which I happily accepted. They were that only two eggs maximum could be taken, one for each of us, but come what may we had to leave at least two eggs in the nest. We also had to remove the eggs in such a way that those remaining were not touched or moved at all. The idea being that our interference would somehow pass un-noticed. Having stolen the eggs we would very carefully pierce each end with a pin and holding it between thumb and forefinger, blow out the contents. This is what was known as blowing an egg. Once empty and dry it could be stored and the start of a collection begun. All this greatly appealed to my hoarding instincts and I still have my egg collection fifty-two years later albeit stored in the loft.

Back at Eccles Hall I now put my newfound knowledge of birds nesting to the test and with a few other children, we set off to see what we could find. I seemed to have gained some confidence since the previous term because I think I was the leader of this little expedition.

So, just like at East Dean, we set off and were soon on our hands and knees tunnelling through scratchy thicket hunting for nests. In these circumstances time stands still as happy hours slide by. At East Dean I never had any sense of time and just waited for my mother to call my name. It is amazing how far her call of “Nigel ...!” could carry. She would stand in the front garden and cup her hands to her mouth and after filling her lungs call, “Ni i g e l l l ...!” She would do this four times but each time changing her direction so that her voice would carry north, south, east and west. She knew I would set off for home immediately, even if it took half-an-hour. In those days there was no traffic and her call only had to compete with bird song or the wind.

But, we were not at East Dean. We were at Eccles Hall and I had found new territory to explore. None of us heard the tea bell and time slid by. I only became aware of how late it was when darkness slowly crept upon us and then, of course, I realised that we were in for trouble.

As the afternoon turned into evening, our teachers became increasingly concerned. Heaven knows what they must have been thinking but they were clearly greatly relieved to see us for by the time we trudged wearily into Eccles Hall it was pitch dark. This however was not the end of the story. We were given a very late tea, sent to bed and told, rather ominously, that the headmaster would deal us later when he arrived in a few days time from London for the weekend.

Time rather dragged in those few days before Mr. Livingston’s arrival. Kathleen Livingston had already told us of the severity of our crime which included the nastiness of birds-nesting as well as the extreme lateness of our return to the school, causing everyone great concern and worry. On Saturday we waited and waited for something to happen. I knew that David Livingston had arrived from London. He had not been struck down with illness, as I had been praying for and looked extremely fit.

Late that afternoon we offending children were called together and once again the severity of our misdeeds was outlined to us. I cannot remember what happened to the others but I was called into Kathleen Livingston’s study where David, her husband, sat looking huge in what was her chair. Again he went over the details before finally standing up. I could not help but be reminded of how big a bear of a man he was. I nervously watched him open a cupboard and gulped as he took out a springy riding crop from within. He then pulled forward a wooden upright chair and told me to drop my trousers. Quietly, he told me to bend over the seat and proceeded to give me what was known in those days as six of the best.

It was very painful and tears fell from my eyes as I pulled up my pants and trousers.

“What do you say, Nigel?” he gently asked of me.

“I am sorry, sir,” I stammered through my tears.

“And what else?” he queried.

“Thank you, sir,” I responded and left the room.

ooooooOOOOOOoooooo

Our expectations were finally rewarded with the first peace on VE day, May 8th, 1945 and at the end of July we left Eccles Hall for good. My delight in packing up my meagre belongings and leaving Eccles Hall was boundless. My whole being surged with happiness. Mother and father collected us from Liverpool Street Station in the Morris and it was like being reborn though now somehow older and wiser. The war was over and the thought of being home again with my lovely family filled me with a terrific excitement. A new life now lay ahead of me, free from bombs, air-raids, fear and destruction.

Contributed originally by Researcher 249331 (BBC WW2 People's War)

In September 1940 the bombing raids really started. The warning would start wailing very loudly, the nearest siren being on top of Stoke Newington Police station, which was almost opposite where we lived. The bombers started coming over every night, the first few nights we sat on the stairs with blankets wrapped around us, shivering from cold - or was it fear? All of us were very quiet listening to the pulsating sound of the bombers overhead.

After a few nights of discomfort we started going into the basement of our next door neighbour. We couldn't use our cellar, as it was full of bundles of firewood that were in stock to be sold in the winter - they were sold for tuppence a bundle, in my father's greengrocery shop. The Vogue cinema was at the other end of of the block of buildings where our shop was situated. It was the sort of cinema that when the film was over you waded through monkey nut shells, on your way out to the exit.

The Blitz comes close to home

One night a bomb dropped onto a bus outside the Vogue. It made a large crater, and fractured a water main. After a while, water seeped into the cellar we were in. As we were hearing a lot of noise from the anti-aircraft guns, and from the dropping bombs, it was decided to go over the road to a proper shelter under the Coronation Buildings, where there was a very large air raid shelter.

We came out and saw the sky criss-crossed with searchlights. Whilst we were running across the road, a bomb landed with an enormous bang on the West Hackney Church. The blast blew out the windows of The Star Furnishing Company windows. The huge glass windows just disintegrated, and fell to the ground like a beautiful waterfall, with all the noise and dust. We rushed into the shelter, but amazingly we were all untouched.

During the day I used to watch the occasional dogfight overhead, and like most boys of my age (I was 11) at the time, my hobby was to go around looking for bits of shrapnel. One morning, coming home from the shelter over the road, I found an incendiary bomb on the pavement outside our shop. I stupidly picked it up, and was examining it when a policeman appeared and said 'I'll have that' - and ran across the road to the station with it.

Shelter

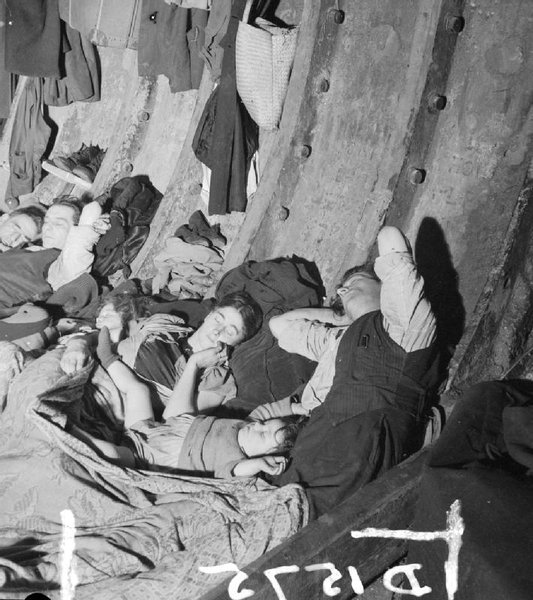

Coronation Avenue buildings consists of a terrace of about 15 shops with five storeys of flats above. The shelter was beneath three of the shops.The back exit was in the yard between Coronation Avenue and another block of buildings, called Imperial Avenue. We went over the road to the shelter whenever there was a raid, and when the 'all clear' sounded in the morning, we would go back over the road, half asleep and very cold, and try to go back to sleep in a very cold bed.

The shelter consisted of three rooms. The front entrance was in the first room, the rear entrance was in the third room, which had bunk beds along one wall.The rooms were jam packed with people, sitting on narrow slatted benches. I would sit on a bench and fall asleep, and wake every now and then, and would find myself snuggled up to my mother and sister. My father had the use of one of the bunk beds, because the men were given priority, as they had to go to work.

Direct hit

On 13 October 1940, the shelter received a direct hit. We had settled down as usual, when there was a dull thud, a sound of falling masonry, and total darkness.

Somebody lit a torch - the entrance to the next room was completely full of rubble, as if it had been stacked by hand. Very little rubble had come into our room. Suddenly i felt my feet getting very cold, and I realised that water was covering my shoes. We were at the end of the room farthest from the exit. I noticed my father trying to wake the man in the bunk above him, but without success - a reinforcing steel beam in the ceiling had fallen down and was lying on him.

The water was rising, and I started to make my way to the far end, where the emergency exit was situated. Everybody seemed very calm - with no shouting or screaming. By the time I got to the far end, the water was almost up to my waist, and there was a small crowd clamberinig up a steel ladder in a very orderly manner. Being a little more athletic than some of them, and very scared, I clambered up the back of the ladder to the top, swung over, and came out into the open.

It was very cold and dark, and I was shivering. The air was thick with brick dust, which got into my mouth, the water was quelching in my shoes. I still dream of, and recall, the smell of that night, and the water creeping up my body. My parents and my sister came out, and we couldn't believe the sight of the collapsed building. My brother had been out with a friend - so was not hurt, and we were all OK.

My mother, sister and I went over to number 6, and my father and brother stayed to see if they could help in any way. Some bricks had smashed the shutters in front of the shop, and had to be replaced with panel shutters, which had to be removed morning and evening. The windows were blown out, and were replaced temporarily with a type of plastic coated gauze.

Afterwards

The next morning, we were told that only one person had survived in the other two rooms, and about 170 people had been killed. (In recent years I have been to Abney Park cemetery, where there is a memorial stone, with names of a lot of the victims who must have died in our shelter.)

There was a huge gap in our building, on about the third floor. There was part of a floor sticking out, with a bed on it. Someone said the person in it was OK, but this story might just have been hearsay.

A lot of the women used to bring photographs of their families to show each other during the long periods of waiting in the shelter. That evening my mother had brought a handbag full of photos to show some women, and fortunately she had not gone into the other room to show them. The photos were never recovered. My sister said she was alright, until she went up into our parents room the next morning, and saw soldiers arriving outside, with shovels - then she started crying (she was 15 years old).

A few days later, I saw men wearing gauze masks bringing out bodies, and placing them in furniture vans. Having seen bodies since, this is the only thing that comes back in my dreams - the furniture vans and the water.

Where next?

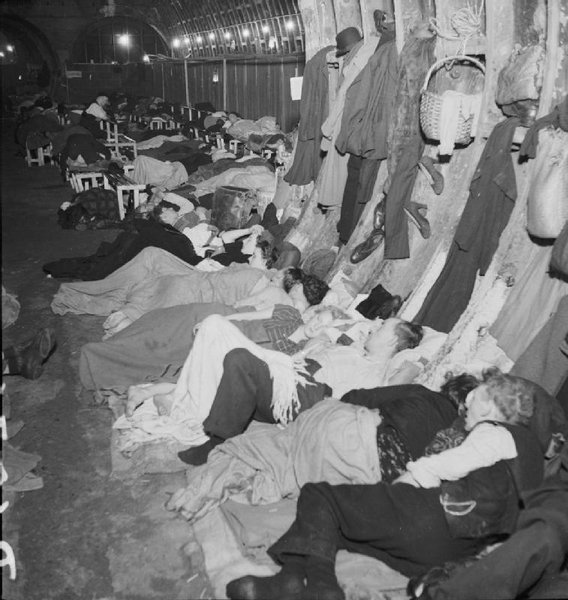

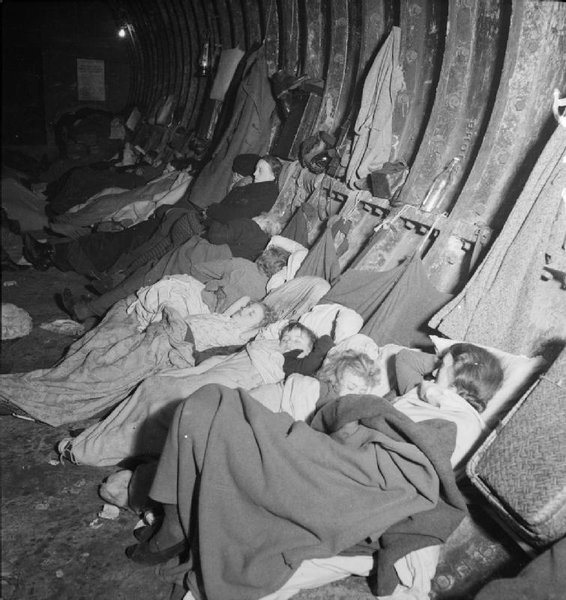

Having nowhere to go for shelter, my parents decided that we would go to the Tube station to sleep. We would close the shop early, and with bundles of blankets go to Oxford Circus station, via Liverpool Street, and sleep for the night on the platform. When the trains started to run the next morning, we would get up feeling very dry and grubby having slept fully clothed all night. We had to wait patiently until the platform cleared, and then back we went to Liverpool Street, and the 649 trolley bus home.

One night we heard a lot of noise above, and the next morning I went up to have a look, and saw a lot of Oxford Street burning. On the way home by trolley bus - amazingly they were still running - we went through Shoreditch, and saw fires still burning. But the motto everwhere was business as usual.

Looking for shrapnel when I got home, I saw an Anderson shelter in Glading Terrace that had received a direct hit - it was just a twisted lump of metal. The bombing was very heavy and some areas were roped off because of unexploded bombs. But it was a pleasant surprise when the King and Queen visited Stoke Newington - that was when I first had my photo taken with the Queen.

Photo with Queen Elizabeth

A water main near us had been had been hit, and my sister and I were trying to find a bowser lorry to get some water, when somebody told me that the King and Queen were in Dynevor Road, nearby. So I ran there, and managed to sqeeze through to the front of the crowd. The Queen made some comment about me to the woman behind me. Some time later my sister saw the photograph taken at the time, and contacted the newspaper and got some copies.

Eventually my parents arranged for my sister and me to be evacuated, and my brother (who was 19 years old) was posted to North Africa. He went from Alemein right through to Italy, and came home and went to the continent - finishing his war in Germany.

Contributed originally by janineshaw (BBC WW2 People's War)

Below are the memories from the Shaws as children which has been extracted from the family book I created last year called ‘Our Tribe – our stories in your words’ which personally recorded the family memories past and present day. Five of the eight family members tell their very unique stories having been separated and evacuated to different families and how they were re-united as a family before the end of the war. Two of the eight have died (Harry and Rita though still mentioned) and the youngest Siddy was not born until after the war.

The family name was Schevitch and they lived at 160 Old Montague Street, London E1. After the Second World War they changed the family name, many foreign and Jewish people changed their name and the spelling of foreign names were changed to more English names to aid this and avoid discrimination. They became The Shaws in around 1947-8.

By Maurice 11-12-1932;

I remember when I was seven, at the outbreak of war, we all went to our school, had labels put on our lapels and were sent to Liverpool Street station. I, with my brother Harry and Leon went on a train down to Ely (near Cambridge) and then to a village called Wilburton and later to Streatham. I was evacuated there for the duration of the war. We went to a big hall where the local people came to pick out children they wanted to stay with them. First I stayed with a woman near Ely who looked after an old lady who I stayed in the same village as all my brothers. She had a clubfoot so couldn’t walk properly and we were on a farm. She was quite strict with us, it was in the middle of winter when Harry, Leon and I went for a walk near an iced over pond. We could see steps from other people who had walked over, we walked across and I fell in! I went under the ice and Harry got in to drag me out, saving me. We were freezing cold and frightened to go home because we would get told off, but eventually went home. The old lady died and her family came down so we all had to move as they sold the farm.

I then lived with the Curtis family and Mrs Curtis who worked on the railway crossing opening, and closing the gates and working the signal box. She was very strict and made me eat all my food like Yorkshire Pudding that I really hated! Mr Curtis was the local cobbler of the village. They had a son, who went into the army who I went pike fishing with which I enjoyed. I used to work on his allotment and as he was the local cobbler I helped to pick the shoes up and take them back to the customer’s houses.

He had a lot of chickens in an orchard that I fed every day and brought back the eggs to our home. In the summertime, when I was about nine, I had to take the chickens in a barrow in cages across four miles of land to feed on the cornfields after they had been harvested. After they had been there for a few months I had to bring them back, and they had grown much bigger and I had to stuff them back into the cages and some of them got suffocated! I was scared to go home as I thought I’d get in trouble and it upset me. We sold them to a few of the Jewish families in the village.

I worked hard during this time and saved my pocket money for it, which I sent home for my mum to look after. I never saw my family for months on end but she sometimes sent cake in food parcels. When my parents did come to see us they would come on the bus and arrive at the church. I was always embarrassed and would hide behind the gravestones!

I remember going blackberry picking and then selling on the berries to a man who bought them up and distributed it and sold it to other areas. I liked looking after the Chinchilla rabbits at the farm. I was also paid to dig holes in the school and distribute the sewage from the toilets in them!! I didn’t do it long. When I was still evacuated I hardly went to school but we had separate schools from the local children, being taught by the evacuated teachers from London. They would be paid eleven shillings a week to stay there and work with us.

All the locals used to call us ‘Jew boys!’ Harry used to defend us all in the village. Him and Gerald Singer were the two toughest and would fight the local boys who would pick on us. You had to stand up for yourself. Harry used to stay at the Parishes, who were farmers and cold merchants so he worked hard on their farm. The family had a son the same age as Harry who would get him into trouble so he was bullied a lot by the family.

I remember when the Curtis’s sent me to the next village, to the fish and chip shop and while I was queuing up some local thug started picking on me and I had my first fight! I didn’t know until then that I was a good fighter but I gave him a real thrashing! I was still very shy and if a girl talked to me I would go blood red in the face!

I remember when I was living in Streatham, a friend of mine from London; Ivan Saffie, came (I don’t know how he knew where to find me!) and bought me a newspaper with pictures and a story of my sisters, Helen and Sylvie who had been evacuated together in a place called Little Hampton, with the Honoured Lady Littleton. They were fast asleep holding hands in their cots (see The Daily Mirror page 7, October 18th 1940). They lived in a really big house and had maids. I almost forgot I had sisters during the war!

My sister Rita was evacuated to Newmarket with a family who worked with racehorses. She remained in contact with them for a long time after the war.

My friend Ivan Saffie went home before the end of the war, back to where his family lived in Valance Road, in Stepney. He was in a block of flats when one of the first doodlebugs bombed the area. He was killed with his family, as well as many other Jewish people and hit St. Peter’s Hospital. The queen mother came to see the debris. The head of the Brady Girls Club, who was also a judge, came to collect all the things that were found and was responsible for handing it back out to the families. Ivan and his family were wonderful people and it was really sad.

By Leon 18-5-1934;

I can’t remember much before the age of five but my first memory started in school - The Robert Monte Fury School in Valance Road, in East London. I had only been at school for about four weeks when war was declared. At that time we lived at 160 Old Montague Street, E1, and in those days we didn’t travel much further than E1. Four weeks after the outbreak of war, evacuation started and my older sister Rita went to Newmarket; she was the first to leave. Harry and Maurice went to Streatham, near Ely, in Cambridgeshire. I was sent to South Wales and a little later on Sylvia and Helen went to Northamptonshire.

About six weeks after my evacuation I was sent back to London because I was so unhappy at the time - I was crying all the time; it was such a shock to my system being away from everyone. I remember having a gas mask given to me in a square box with a piece string which we hung around our necks, and a package label saying who I was and where I was going. When I was sent back to London it had completely changed because the Blitz and air raids had started. We had to take our gas masks everywhere and black-outs took place every night from as soon as it got dark. This meant that no light could be shown at night and wardens would come around the streets to check up on this. Barrage balloons were in the sky - they were oval shaped and the idea was that the German planes would not fly low and if they did they would bash into them and crash. Rationing had started and there were queues for everything, especially for food. The radio was the main focal point for any news.

One particular night that I remember was when the air raid siren started, bombs started dropping, and I cannot remember if we had one or two babies at the time, but my mum put the baby in the pushchair, grabbed me, rushed out on the street and I tried to go around to the air raid shelter in Whitechapel Road, about a quarter of a mile away. At the time there was bangs, crashes, machine gun fire, search lights in the sky and buildings on fire, rubble and dust coming from the bombed buildings. There were parachutes with flares on, and when we got to the shelter there were wooden gates on the shelter which were locked, I presume the ARP (air raid prevention people) hadn’t got there in time and opened it yet!! My mother with other people who were trying to get in, used the pushchair to bash down the gate and we got in. There were like cellars under the shops. Even if I hear an air raid siren today I still get a bad feeling inside me, which reminds me of the scare I had at the time.

Within a couple of weeks of this incident I was evacuated to the same village as Harry and Maurice. Harry was with Cyril Parish; Maurice was with a Mrs Curtis and I was put with Mr and Mrs Bulmer. They didn’t want me and they used to let me know quite plainly! I was pushed about and given quite a lot of verbal abuse. After one very bad day with them, I mentioned this to Harry and Maurice when I saw them, and they were going to beat them up. Harry was about ten and Maurice was eight!! God bless them both for looking after me during the hard, hard years!

During the war years, when the children were away evacuated my parents didn’t have much contact with us. As far as my father was concerned, being foreign (Polish/Russian) he was treated as an alien and his travel movements were restricted. He had to register with the police and not allowed to travel. Also during this time my mother always had young children to look after. My mother would come and see the boys in Streatham about once a year yet in those days being sixty miles from London was a huge distance. Travel was only for military purposes too.

We went to school but had no real classes, all evacuees together. This meant that we had no education until we returned to London in 1945. I remember going out on a cold winter’s day with Harry and Maurice and we went over to the river into some fields and they walked straight over a pond that was frozen. When they came back and got to the middle the ice broke and they went straight in!! They just about managed to scramble out soaking wet. I didn’t do it as I was too much of a coward and stayed by the side!!

One other incident I remember was going over the fields, and after a mile we sat down by an old wooden tree that had blown down. Harry started shouting and then we could see that we had sat down on a hornet’s nest in the tree!! I remember us all running like mad, and we just about out-paced them!

Harry lived with the local coal merchant, with 95% of the homes being heated by coal in those days. He had to go out most weekdays helping to deliver the coal, which was very tough for a kid his age. On a number of occasions we discussed running away to get home, that London was only 60 miles away but in those days it was like being in another world!! There were only three cars in the village owned by the doctor, the vicar and the teacher!!

By Sylvie;

There was no early home life that I can recall with my family until I was nine because I was too young before that to remember. I remember the foster homes that I stayed in. I was three during the war almost four. We (Helen and I) went when the London blitz started (September 1940 - May 1941) it was mandatory. I remember the spaciousness of the place, the nurses that took care of us. There were twenty other children there and I had so much fun with them. We stayed an English estate home of air chief-marshal Sir Robert Brooke Popham, in Northamptonshire. I could only stay there until I was five when I was snuck off, separated from my sister and taken to a new foster home. I remember clinging to my sister as seen in the paper during the first placement.

In my next foster home I was taken to another stately home, this time of Lady Littleton and her two spinster sisters. Those times were very happy, in beautiful surroundings, with a private gardener and other people working around taking care of the property. One thing I recall was having my own playroom and the toys there waiting for me. I never sat with the spinsters at the main table in the dining room. I had my own table in the corner. The women were very kind and my needs were taken care of but I got no hugs or kisses for the whole of the war years.

Helen joined me a year later. I was taken for a walk to where she was living and we met on a hill. I was very happy to see her but I got into trouble because I was possessive with my toys and didn’t want to share them with her; I was scolded for that. We got driven around in the nice car but for some reason I have no recollection of going to school, having friends or the teachers!!

We both moved when I was seven to a farming family in the same area. They had four other children Ted and Alice I remember. It was a sharp contrast to the luxury I was in before. They were a nice family based right on the high street (18 High St., Brackley). We would have a meal called 'spotty dick' with fatty meat which I could not tolerate! I would have to hide it in my handkerchief and dispose of it when I left the table. I also remember Sunday mornings covering the whole big dining table with newspaper and everyone had to put their shoes up on the table and polish them together as a ritual. During the latter part of our stay I realised the Germans were so close to us in France and the family asked us to take off my gold star and said they would give it back to us at another day. I now understand why they did that to protect us. We also all went to church together which I really enjoyed with the family. We would be given a bag of goodies too so it was a day that I enjoyed.

They would have May Day celebrations in a park near to my house. They would have a May pole and it was the only place I remember seeing one to this day! We all of us danced around it. There was a bit of different language and funny expression that I learnt with an accent to go with it. For example they said 'you frit me' instead of you frightened me! We picked up the accent too!

In the main street there was a big building that housed Italian Prisoners of War who were allowed to sit on the side of the steps. We were told that we were never to go up to them or associate with them. I also remember the odd tank going through the country roads and being told by the other kids when we saw any American or Canadian soldiers that we had to say 'do you have any gum chum?!'. We heard the odd air raid siren but nothing like that experienced by Dena in London.

I didn’t miss my mum or my family as I was too young to remember them - we knew they existed but can’t recall hearing from them over the time. I do remember receiving sweeties from my grandmother on at least one occasion though.

On my eight birthday at the farm family they made me a dolls house made out of cardboard. It was painted and I just loved it!

By Helen 12-1-1938;

I remember an incident that I haven’t forgotten. I was evacuated during the war at aged two with my sister Sylvia. She became the closest person to me as far back as I can remember, having been taken away from my parents. We went to two stately homes which were lovely and large, with other children as it was turned into a nursery. The most upsetting thing was that at age four Sylvia had to leave and as we were so close they decided to take her away in the night. I remember waking up screaming when I realized she had been taken away.

During this first placement, I had problems with my speech and only my sister could understand me as I was always with her. She would interpret what I was saying and I had so many people trying to help me I developed a stammer because I was so conscious of it!!

We were brought back together after a year but we had to get to know each other again. I feel it was very wrong to separate us in the first place. My mum (and Rita sometimes) would come and visit but not my dad who was always working. My mum was seen as more like a friend than a mum as she was not our main carer at the time.

Harry was older and much more aware of the awful time he was having where he was. I remember reading a book which said between the ages of two and five are very important ages for attachment, so being taken away during this time had lasting affects. Both Leon and I talked about this and agreed how hard it was for us. There are a lot of people who tried to claim compensation from the government for damages done during war times and during foster placements. Can you imagine if we all tried to claim for our traumas through the Second World War?!

After being with my sister for two years, we went to Lady Littleton’s home and it was very lovely and quiet there. The women working there were kind but it was all so orderly and we had to do different things on different days. The three ladies were around a lot and there were lovely orchards to play in. They also had some Italian prisoners of war who made baskets out of branches. They wanted to make contact with us and talk to us but we were told not to talk to them. We had some happy memories there. After leaving the Littleton’s we went to a big school, and were in a hall with all these other children. We were told we couldn’t be split up and were chosen to live on a farm with six children. We helped out with the farmer and his wife, with the baby chicks and plucking the chickens. We had lots of fresh food when others were having problems with rationing. I also remember playing in the large fields and it was another lovely place.

By Dena 18-2-1940;

I wasn’t born when war broke out but in 1940 so it had been on for one year – I was a war baby!! I was born in Mrs Levy’s home, in Valance Rd., in the East End. London Hospital was the nearest hospital but this was the nearest maternity home.

When I was about two years old I remember being picked up and a blanket being put around me and being carried to the shelter while the sirens were going off. When we arrived at the shelter I remember feeling surprised that all my neighbours were there too. I looked at Mrs Cooper who owned our local grocery store and being surprised that she was there too. They all had bunk bed made up in the underground all along the walls of the platform. I know there was a shelter at the River Lea Court, off Whitechapel High St. but am not sure what the underground station was as Whitechapel was an over ground station.

I was in London all through the war until 1945 and the last six months of the war I was evacuated to Kings Langley. The lady’s home I stayed with was Mrs. Goddard and a friend of mine who lived on my street, Sandra Mildener was there too. I remember during the war years having a wonderful time, and everyone made a fuss of me. I was the youngest of seven at the time and because they were all sent away for safety but my mum kept me close to her. I remember going to the Yiddish play on Commercial Road on a Saturday night and being dressed up like the dogs dinner by my mum. I had a white fur coat, hat and muff and I used to love it.

I don’t remember having brothers and sisters and thought I was an only child. We used to go with Uncle Sam and Aunty Sarah my parents’ friends to the playhouse. Uncle Sam had come over with my dad at the age of fifteen when they had got away from Russia. He adored me and told me he wanted to adopt me!

I remember going to visit my grandparents who lived in Streatham getting on the trolley bus ride which I loved most of all those old fashioned ones. The next thing I remember was my grandmother being ill and going to visit her all standing around the bedside. Me being a kid jumped on the bed and got shouted at for making noise. She had cancer at the time.

I remember coming home one day and there was loads of rubble at the end of our street where a bomb had hit the other side of the street. It became our playground for years until there cleared it. I remember playing on the bricks and balancing on the beams as there was all that was left of these skeletons playing in the ruins. I used to stand on the top singing ‘I’m the king of the castle!’

Reunited in London

By Leon;

We came back to London just before the end of the Second World War. Bombing had stopped, except for the doodlebugs and rockets which came a little later, which made it much safer. It was very near the end for Hitler and authorities were allowing the children to come back. Just after we returned one of the rockets came down on London, to Vallance Rd., near where we lived. It killed a lot of people, including some family friends of ours. We had moved to 117 Old Montague Street, to a bigger house, with three floors; boys in one bedroom, sleeping two per bed, head down one end and feet the other - head to feet. The girls slept in the other bedroom. My dad would be out working in the markets from before we got up in the morning until late in the evening - he mainly sold linens. My mum worked part time jobs occasionally, what she did I didn’t remeber.

We were very poor, but with everyone around you in the area is in the same position, you don’t notice it. We had very little toys or games. One of the very best things we all had was Brady. This was a girls’ club in Hanbury Street, and a boys club in Brady Street. It was open five days a week, not on a Friday night or Sunday evening. We had a great time there, this took the kids off the street, which was an excellent thing. Anybody could belong to it, and paid a nominal fee to go. For the boys there were cards, snooker, boxing a gym, with a small canteen. We also had a summer camp on the Isle of Wight, which were the first holidays we ever had as kids. Occasionally we could go away on weekends, to a house down in Kent, called Skeet Hill house, to go to.

By Sylvie:

I don't remember actually leaving the family but I do remember arriving in London after the war getting off the train and onto a bus to go to a school. I found it frightening, smelly and quite mind boggling because of the noise. I was taken to the school and my mother picked us up. Somehow she wasn't a stranger when we saw her and she took us home. The street had a lot of bombed buildings in every direction. In particular the old Montague Street School was still standing but looked like it was ready to collapse. Within a few hours of arriving she took us to the Evada children's wear store on Whitechapel Road and bought us new identical dress each.

Our mum and dad, and brothers and sisters were all total strangers to us when we returned from evacuation after the war. I don’t recall having any feeling of apprehension about this new life situation that we were faced with. After all we were all experiencing the new adjustment. Personally I was happy and accepting even though the trauma of leaving the beautiful English countryside and seeing the devastation of the bombing of London especially our neighbourhood, was quite depressing. I guess we were a tough bunch of kids; we got acquainted with each other and resigned ourselves to our new lives. We overcame a lot of obstacles mainly due to financial hardship. However I don’t believe any of us went hungry, we also had adequate clothing. We grew to love one another and shared good times. Plenty of squabbling went on but our home was often filled with the sound of music too, all kinds of music from opera to Yiddish, to marching bands to Frank Sinatra and my favourite, Billy Ekstine and Sarah Vaughan. We made good use of our record player.

I think our parents must have been overwhelmed by the sheer enormity of the task of feeding, clothing and caring for so many of us, who all arrived on the scene so suddenly at the end of the war. We learned that our Dad’s almost entire family had died in Auschwitz concentration; camp, he never spoke of them. Not very many of either of our parents’ background was passed on to us by them, however even now when us brothers and sisters get together a new revelation might be shared. Had they lived longer, I would have pestered them to tell us so much more. We were all left at such a young age with a huge void in our lives and I don’t believe any of us recovered from the suddenness of losing our mother in her 48th year.

By Helen:

We were told that we were going to return to London and the daughter of the framer and his wife said that in London there were no fields or trees and it made me feel so sad!! She was wrong but right in one way because of the ruins and devastation that I found when I arrived which I wasn’t prepared for. We went off to London with our labels on our lapels and went on a double decker bus to a school hall and families came to collect them. Some children had nobody coming to collect them as their parents didn’t want to know them after the war i.e. from illegitimate children to US or Canadian soldiers.

I remember walking along Old Montague Street with my sister, dad and mother. This big dog came barking up to us! It was Queenie our family dog. We also had Succkie and Teddy afterwards and they were all Chow breeds. They were louder, a little rougher and different to suburban pets. We arrived home with bombsites everywhere and open buildings where the kids played which were death traps really. Such a complete contrast to where we had lived during our fostering.

We arrived in the kitchen and somebody said ‘listen to how they are talking!’ after I had said ‘can I have some jam please?’, in a posh accent. I felt quite different from the rest of them after my time away and it took time to get to know each other again. I was conscious of my country accent. The boys used to bully the girls because they had been disturbed by their experiences.

We had one kitchen at the back of our house, which was like a scullery. We only had cold running water, a gas cooker and wooden table, and back yard. The whole family, nine of us at the time had to wash there, but when it was bath time we only had a metal bath with water poured from the fireplace, and the three younger girls were bathed together in this boat like tub. There was a time when there was a shortage of fuel when I was about eleven and every family was rationed one sack of coal. We had to go and collect the coal from Flower and Dean Street (or Fashion Street) and had to line up. What we decided to do was to all go down there and line up and pretend we didn’t know each other and then carry them back on our backs and they were so heavy!!

By Dena;

The strangest thing for me was that I don’t remember my brothers and sisters coming back even though I loved them coming back. One minute there was nobody there and the next minute there was a house full it was like a party everyday. We moved from one side of the road to the other after the war, as there was more space in a bigger house. There were seven rooms, and four bedrooms, and all the girls slept in one room, my parent in the other and the boys split between the other two smaller rooms.

Contributed originally by Billericay Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

1

I was born in a two bedroom flat in Shoreditch. I was the youngest of three children. My sister Beatrice but called Sis was three years older than me and my brother Vicki was three years her senior. My father, who was ten years older than my mother, suffered form a stomach ulcer and successive haemorrhages necessitated his removal to hospital at frequent intervals. Even when in good health, this being the years of depression, work was hard to find, and money was often a cause of dissension between my parents. Even so, from old photographs we all appeared to be plump and well cared for.

Hamilton Buildings, as our flats were called, had a large asphalt playground in front of them, gardens were non-existent. Our complete surrounding consisted of grey brick scooters out of orange boxes with ball bearings for wheels. Everyone knew everybody else in these flats, which was not surprising as none of them had bathrooms or toilets. These, meaning the toilets, were at the end of a passage and they were shared by at least four families.

I started school just after my third birthday. This was quite a usual practice at the time, as it enabled the mothers, some of whom found it easier to find employment than their husbands, to leave their children. I cannot remember much about school except that anyone naughty enough to swear was taken to the washroom and made to rinse their mouth out with carbolic soap. I think this must have deterred them for life.

My father’s family who lived next door to a church in St. John’s Street were very religious and, although to the best of my knowledge he never darkened a church door, we were all duly dressed in clean, white ankle socks and packed off there each Sunday. After church we visited our grandparents and on the way home we stopped at a pub in the main road, where by this time on a Sunday my father could be found and where we were sure to get a glass of lemonade.

About the middle of 1939, when it became obvious that a war was inevitable, arrangements were made for the whole school to be evacuated. We were issues with gas masks and out clothes were packed and deposited at school and each day we went to school with a fresh pack of sandwiches just in case it was the day to go. No one, not even the staff, knew our destination. It never ceases to amaze me that so many parents were prepared to go along with this. Three days before war was declared, off we went in a long line, with our bags and gas masks and a label stating out name tied on us to Liverpool Street station; that evening our train came to a halt at Hunstanton in Norfolk. Here we were out in coaches and driven around the town and were literally dumped on anyone with sufficient room to accommodate us.

2

My brother and sister, five other children and myself were placed in the home of a well to do spinster who lived in a large villa on the outskirts of the town. She protested strongly to the billeting officer at the imposition of having us thrust upon her. He assured her that he would do his best to find us other billets as soon as possible. She had a plump housekeeper named Mrs Williams and we were relegated to her charge in the kitchen while she withdrew to her drawing room.

Our parents were informed of our whereabouts and on the Sunday my mother and father arrived to see if we were alright. Such was the nature of our unwilling hostess that she would not even invite them into the house. Dad was furious at being treated this way and was all for taking us straight home again but my mother, fearful about the war, prevailed on him to let us stay.

After three weeks of trying to cope with eight children in her kitchen, Mrs Williams protested to her employer, who in turn protested to the billeting officer, and then my brother and the three other boys were taken to another billet in the little village of Old Hunstanton three miles away. So our family was broken down one stage further.

My sister and I stayed here for about two months, and then late one autumn afternoon, we were also taken to a new billet in this village. It was about five o' clock and already dark when we arrived at the tiny thatched cottage. The door opened to reveal a short old lady who held an oil lamp in her hand; her hair was scragged back into a bun and her face withered and wrinkled. I was terrified of her. To me, six year old with a vivid imagination, she looked just like an old witch. I clung to my sister and it was weeks before I regained the confidence to let her out of my sight.

Granny Matsel, as the old lady became known to us, was a very good old country woman and she cared for us very well. Mt fear departed and I began to take notice of the countryside around us.

The winter came and was very severe with a very heavy fall of snow. An eight foot snow drift blocked the lane, cutting us off from the other end of the village. The village pond froze and the children made a long slide on it. I think this must have been my first experience of snow and I was delighted with it. All the trees and bushes coated with frost made everything look like fairyland. We settled down here very well. We went to the local village school and the old Norman church. Every Saturday we went to the cemetery to tend the grave of Granny's husband. Everything in this cemetery was so well kept and peaceful that death held no terror for me. Somehow the sense of oneness with creation, which country people seem to possess and which gives such tranquillity to their natures came into me and I was happy.

3