Bombs dropped in the borough of: Enfield

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Enfield:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 571

- Parachute Mine

- 7

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

No bombs were registered in this area

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

No bombs were registered in this area

Memories in Enfield

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by BoyFarthing (BBC WW2 People's War)

I didn’t like to admit it, because everyone was saying how terrible it was, but all the goings on were more exciting than I’d ever imagined. Everything was changing. Some men came along and cut down all the iron railings in front of the houses in Digby Road (to make tanks they said); Boy scouts collected old aluminium saucepans (to make Spitfires); Machines came and dug huge holes in the Common right where we used to play football (to make sandbags); Everyone was given a gas mask (which I hated) that had to be carried wherever you went; An air raid shelter made from sheets of corrugated iron, was put up at the end of our garden, where the chickens used to be; Our trains were full of soldiers, waving and cheering, all going one way — towards the seaside; Silver barrage balloons floated over the rooftops; Policemen wore tin hats painted blue, with the letter P on the front; Fire engines were painted grey; At night it was pitch dark outside because of the blackout; Dad dug up most of his flower beds to plant potatoes and runner beans; And, best of all, I watched it all happening, day by day, almost on my own. That is, without all my school chums getting in the way and having to have their say. For they’d all been evacuated into the country somewhere or other, but our family were still at number 69, just as usual. For when the letters first came from our schools — the girls to go to Wales, me to Norfolk — Mum would have none of it. “Your not going anywhere” she said “We’re all staying together”. So we did. But it was never again the same as it used to be. Even though, as the weeks went by, and nothing happened, it was easy enough to forget that there was a war on at all.

Which is why, when it got to the first week of June 1940, it seemed only natural that, as usual, we went on our weeks summer holiday to Bognor Regis on the South coast, as usual. The fact that only the week before, our army had escaped from the Germans by the skin of its teeth by being ferried across the Channel from Dunkirk by almost anything that floated, was hardly remarked about. We had of course watched the endless trains rumble their way back from the direction of the seaside, silent and with the carriage blinds drawn, but that didn’t interfere with our plans. Mum and Dad had worked hard, saved hard, for their holiday and they weren’t having them upset by other people’s problems.

But for my Dad it meant a great deal more than that. During the first world war, as a young man of eighteen, he’d fought in the mud and blood of the trenches at Ypres, Passhendel and Vimy Ridge. He came back with the certain knowledge that all war is wrong. It may mean glory, fame and fortune to the handful who relish it, but for the great majority of ordinary men and their families it brings only hardship, pain and tears. His way of expressing it was to ignore it. To show the strength of his feelings by refusing to take part. Our family holiday to the very centre of the conflict, in the darkest days of our darkest hour, was one man’s public demonstration of his private beliefs

.

It started off just like any other Saturday afternoon: Dad in the garden, Mum in the kitchen, the two girls gone to the pictures, me just mucking about. Warm sunshine, clear blue skies. The air raid siren had just been sounded, but even that was normal. We’d got used to it by now. Just had to wait for the wailing and moaning to go quiet and, before you knew it, the cheerful high-pitched note of the all clear started up. But this time it didn’t. Instead, there comes the drone of aeroplane engines. Lots of them. High up. And the boom, boom, boom of anti-aircraft guns. The sound gets louder and louder until the air seems to quiver. And only then, when it seems almost overhead, can you see the tiny black dots against the deep, empty blue of the sky. Dozens and dozens of them. Neatly arranged in V shaped patterns, so high, so slow, they hardly seem to move. Then other, single dots, dropping down through them from above. The faint chatter of machine guns. A thin, black thread of smoke unravelling towards the ground. Is it one of theirs or one of ours? Clusters of tiny puffs of white, drifting along together like dandelion seeds. Then one, larger than the rest, gently parachuting towards the ground. And another. And another. Everything happening in the slowest of slow motions. Seeming to hang there in the sky, too lazy to get a move on. But still the black dots go on and on.

Dad goes off to meet the girls. Mum makes the tea. I can’t take my eyes off what’s going on. Great clouds of white and grey smoke billowing up into the sky way over beyond the school. People come out into the street to watch. The word goes round that “The poor old Docks have copped it”. By the time the sun goes down the planes have gone, the all clear sounded, and the smoke towers right across the horizon. Then as the light fades, a red fiery glow shines brighter and brighter. Even from this far away we can see it flicker and flash on the clouds above like some gigantic furnace. Everyone seems remarkably calm. As though not quite believing what they see. Then one of our neighbours, a man who always kept to himself, runs up and down the street shouting “Isleworth! Isleworth! It’s alright at Isleworth! Come on, we’ve all got to go to Isleworth! That’s where I’m going — Isleworth!” But no one takes any notice of him. And we can’t all go to Isleworth — wherever that is. Then where can we go? What can we do? And by way of an ironic answer, the siren starts it’s wailing again.

We spend that night in the shelter at the end of the garden. Listening to the crump of bombs in the distance. Thinking about the poor devils underneath it all. Among them are probably one of Dad’s close friends from work, George Nesbitt, a driver, his wife Iris, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Eileen. They live at Stepney, right by the docks. We’d once been there for tea. A block of flats with narrow stone stairs and tiny little rooms. From an iron balcony you could see over the high dock’s wall at the forest of cranes and painted funnels of the ships. Mr Nesbitt knew all about them. “ The red one with the yellow and black bands and the letter W is The West Indies Company. Came in on Wednesday with bananas, sugar, and I daresay a few crates of rum. She’s due to be loaded with flour, apples and tinned vegetables — and that one next to it…” He also knows a lot about birds. Every corner of their flat with a birdcage of chirping, flashing, brightly coloured feathers and bright, winking eyes. In the kitchen a tame parrot that coos and squawks in private conversation with Mrs Nesbitt. Eileen is a quiet girl who reads a lot and, like her mother, is quick to see the funny side of things. We’d once spent a holiday with them at Bognor. One of the best we’d ever had. Sitting here, in the chilly dankness of our shelter, it’s best not to think what might have happened to them. But difficult not to.

The next night is the same. Only worse. And the next. Ditto. We seem to have hardly slept. And it’s getting closer. More widely spread. Mum and Dad seem to take it in their stride. Unruffled by it all. Almost as though it wasn’t really happening. Anxious only to see that we’re not going cold or hungry. Then one night, after about a week of this, it suddenly landed on our doorstep.

At the end of our garden is a brick wall. On the other side, a short row of terraced houses. Then another, much higher, wall. And on the other side of that, the Berger paint factory. One of the largest in London. A place so inflammable that even the smallest fire there had always bought out the fire engines like a swarm of bees. Now the whole place is alight. Tanks exploding. Flames shooting high up in the air. Bright enough to read a newspaper if anyone was so daft. Firemen come rushing up through the garden. Rolling out hoses to train over the wall. Flattening out Dad’s delphiniums on the way. They’re astonished to find us sitting quietly sitting in our hole in the ground. “Get out!” they urge

“It’s about to go up! Make a run for it!” So we all troop off, trying to look as if we’re not in a hurry, to the public shelters on Hackney Marshes. Underground trenches, dripping with moisture, crammed with people on hard wooden planks, crying, arguing, trying to doze off. It was the longest night of my life. And at first light, after the all-clear, we walk back along Homerton High Street. So sure am I that our house had been burnt to a cinder, I can hardly bear to turn the corner into Digby Road. But it’s still there! Untouched! Unbowed! Firemen and hoses all gone. Everything remarkably normal. I feel a pang of guilt at running away and leaving it to its fate all by itself. Make it a silent promise that I won’t do it again. A promise that lasts for just two more nights of the blitz.

I hear it coming from a long way off. Through the din of gunfire and the clanging of fire engine and ambulance bells, a small, piercing, screeching sound. Rapidly getting louder and louder. Rising to a shriek. Cramming itself into our tiny shelter where we crouch. Reaching a crescendo of screaming violence that vibrates inside my head. To be obliterated by something even worse. A gigantic explosion that lifts the whole shelter…the whole garden…the whole of Digby Road, a foot into the air. When the shuddering stops, and a blanket of silence comes down, Dad says, calm as you like, “That was close!”. He clambers out into the darkness. I join him. He thinks it must have been on the other side of the railway. The glue factory perhaps. Or the box factory at the end of the road. And then, in the faintest of twilights, I just make out a jagged black shape where our house used to be.

When dawn breaks, we pick our way silently over the rubble of bricks and splintered wood that once was our home. None of it means a thing. It could have been anybody’s home, anywhere. We walk away. Away from Digby Road. I never even look back. I can’t. The heavy lead weight inside of me sees to that.

Just a few days before, one of the van drivers where Dad works had handed him a piece of paper. On it was written the name and address of one of Dad’s distant cousins. Someone he hadn’t seen for years. May Pelling. She had spotted the driver delivering in her High Street and had asked if he happened to know George Houser. “Of course — everyone knows good old George!”. So she scribbles down her address, asks him to give it to him and tell him that if ever he needs help in these terrible times, to contact her. That piece of paper was in his wallet, in the shelter, the night before. One of the few things we still had to our name. The address is 102 Osidge Lane, Southgate.

What are we doing here? Why here? Where is here? It’s certainly not Isleworth - but might just as well be. The tube station we got off said ’Southgate’. Yet Dad said this is North London. Or should it be North of London? Because, going by the map of the tube line in the carriage, which I’ve been studying, Southgate is only two stops from the end of the line. It’s just about falling off the edge of London altogether! And why ‘Piccadilly Line’? This is about as far from Piccadilly as the North Pole. Perhaps that’s the reason why we’ve come. No signs of bombs here. Come to that, not much of the war at all. Not country, not town. Not a place to be evacuated to, or from. Everything new. And clean. And tidy. Ornamental trees, laden with red berries, their leaves turning gold, line the pavements. A garden in front of every house. With a gate, a path, a lawn, and flowers. Everything staked, labelled, trimmed. Nothing out of place. Except us. I’ve still got my pyjama trousers tucked into my socks. The girls are wearing raincoats and headscarves. Dad has a muffler where his clean white collar usually is. Mum’s got on her old winter coat, the one she never goes out in. And carries a tied up bundle of bits and pieces we had in the shelter. Now and again I notice people giving us a sideways glance, then looking quickly away in case you might catch their eye. Are they shocked? embarrassed? shy, even? No one seems at all interested in asking if they can help this gaggle of strangers in a strange land. Not even the road sweeper when Dad asks him the way to Osidge Lane.

The door opens. A woman’s face. Dark eyes, dark hair, rosy cheeks. Her smile checked in mid air at the sight of us on her doorstep. Intake of breath. Eyes widen with shock. Her simple words brimming with concern. “George! Nell! What’s the matter?” Mum says:” We’ve just lost everything we had” An answer hardly audible through the choking sob in her throat. Biting her lip to keep back the tears. It was the first time I’d ever seen my mother cry.

We are immediately swept inside on a wave of compassion. Kind words, helping hands, sympathy, hot food and cups of tea. Aunt May lives here with her husband, Uncle Ernie and their ten-year-old daughter, Pam. And two single ladies sheltering from the blitz. Five people in a small three-bedroom house. Now the five of us turn up, unannounced, out of the blue. With nothing but our ration books and what we are wearing. Taken in and cared for by people I’d never even seen before.

In every way Osidge Lane is different from Digby Road. Yet it is just like coming home. We are safe. They are family. For this is a Houser house.

Contributed originally by DENBAILEY (BBC WW2 People's War)

A Few World War II Memories of a young Boy

By Dennis Bailey

I was born in September 1938 and was 1 year old when this Country went to war with Germany in1939. I lived in end of terrace house in the north-east area called Freezywater of Enfield in the then County of Middlesex which is just north of London. I had a Mum, Dad and two elder Brothers at the time.

My father worked as a engineering machinist in a factory called ‘Enfield Small Arms’. This was a famous factory, renowned for the manufacture of the Lee Enfield Rifle as well as other weapons of war. His job entailed machining a part of a gun called the ‘bolt’. This was the item, that when the trigger was pulled, fired the bullet.

He worked a shift of between 8 and 12 hours a day, six days a week. He was also a member of the ‘Home Guard’ and after work was expected to be on duty for as long as required while not at work. He would cycle to work (you could not get petrol or even to own a motorcar then) the Factory was about 2 km from our home. The main road, Ordnance Road, to the Factory was 1.5 km long and at the beginning and end of each working shift, this Road was completely full, impassable, with hundreds of cyclists (up to 8 abreast both sides of the road) going to or leaving the Factory. About halfway down, this road crossed a railway, by a level crossing, which was adjacent to the Enfield Lock Station. Of course, the level crossing gates were nearly always closed of the road when the Factory was discharging or receiving its workers and a huge traffic jam of cyclists would be created. There were two foot bridges over the railway, on the opposite side of the road to the station platforms. But the bridge nearest the road had steps and it was prohibited to carry a bicycle over this bridge and the other bridge was accessed by concrete ramps but cyclists were forbidden to ride bicycles on this one. Most days a policeman patrolled these bridges and caught lots of scuttling cyclists each day, trying to get to work, or home, on time. Also if stopped by the policeman, the bicycle would be scrutinized for defects, such as no or not working bell, no or only one working brake, no mud guards, no reflector or white patch on the rear mudguard and if after dark, no lights. The miscreants would have to appear at the magistrate’s court and the standard fine for each offence was 10 shillings (50p). This was a lot of money when the normal pay was only about £5 a week for a male factory worker.

My Mother was a housewife looking after the home, and believe it was mainly her decision, not to send my brothers and myself to be evacuated to the country, so we lived throughout the war in Enfield. Being only a toddler, I did not venture very far from home until September 1943, when I went to a local infants’ school.

Most of the early years of the war, the family lived in an air raid shelter called the Anderson Shelter. This shelter, known as a ‘dugout’ was supplied to our house and my Father with the help of neighbours and friends installed it in the back garden about 20 metres from the house. It was domed shaped with flat ends, approximately 2 metres wide 2.5 metres long and 2 metres high. It was made of made of corrugated, galvanized steel panels bolted to an angle iron frame. The ‘dugout’ was installed in a metre deep hole and covered with an earth mound at least 25 cm thick. The entrance was a 76 cm square hole in the centre of one end, at ground level. Against the entrance hole was a 76 cm cube wooden porch with a hinged door to one side, (facing the house) and a piece of sacking over the entrance to exclude any light from inside the shelter. The porch was also covered, except the door, with earth. The mound of earth covering the ‘dugout’ was sown with grass and in the spring lots of daffodils grew amongst this grass. Four bunk beds in two tiers with a small gap between were put inside the ‘dugout’ I usually shared a bed with my next older brother.

The bunk beds were made of 10 x 5 cm timber frames with steel spring mesh tops. Bedding was made from cushion mattresses (probably from the armchairs in the house) and blankets. The only heating and lighting was from a small paraffin lamp and candles, torch batteries were not available items. A chimney was made from a bent piece of steel pipe to ventilate the lamp with fresh air, (it had to be bent, so as not to show a light at night). In the early years of the war, there was a problem with water seeping into the shelter, so a concrete liner, 10 cm thick, like a bath, was cast into the bottom of the ‘dugout’ (many of these liners exist today as garden ponds). It was always cold, damp and claustrophobic in the shelter; large people found it difficult even to get in the door! To entertain ourselves, we tried to read, write or play board games (e.g. snakes and ladders) by candle light, it was generally too noisy to try and listen to a radio, (there was no television then). Many hours, sometimes days, were spent in the shelter, only emerging for hot food and drink (it was impossible to cook in the ‘dugout’).

Air raids went on almost continually when the weather was good, so you just had to stay under cover. I can well remember the enemy aircraft bombing London (the centre of London was 19 km to the south of or home), the light from the burning buildings, at night, was so bright; you could read a newspaper by it, (if you could read that is!). About 100 metres to the west of our house was an army anti aircraft (ack-ack) site. During an air raid the guns (at least 4 No 3.7 inch guns and a 40 mm Bofor’s gun) were fired repeatedly. The noise and vibration were terrific; our house had nearly every pane of glass broken, in fact by the end of the war, only one fanlight window remained intact. Even the pictures hanging on the walls had all their glass broken. The plaster on the walls was cracked and the roof tiles constantly had to be replaced because of the falling shrapnel and vibration. All the damage was repaired and made good after the war. At night the sky was also ‘lit up’ by searchlights, pencil like beams of bright light, that swept the sky for aircraft, and sometimes, with tracer shells weaving their patterns, it was brighter than bonfire night, but much more deadly.

In 1941 a shell fired by this battery went astray and hit our house. It penetrated the upstairs external wall into the small bedroom, turned 90 degrees, went through an internal wall and ended up in my cot, fortunately (for me) I was in the ‘dugout’ at the time. This AA battery was observed by a German aircraft, which tried to bomb it, but the bomb landed on the front door step of a house in the next road north of ours and demolished the house. The bomb blast also blew the roof off our house, but this was quickly repaired by the emergency people.

The AA battery was attached to a small temporary camp, which was a set of wooden billets surrounding a parade ground, with white washed kerb stones and a flag pole in the middle. The camp was surrounded with a fence of coiled barbed wire and had its main entrance in Bullsmoor Lane, after the war a housing estate was built over the site. You could hear a bugler play Reveille in the mornings and Last Post at night. Towards the end of the war it became a prisoner of war camp, housing mainly captured Italians. These prisoners were allowed out to work in the many greenhouses in the area, growing tomatoes and cucumbers.

One of my memories of these dramatic days was of the street gangs (of mainly boys), who used to assemble to play street games. They used to play cricket and football in the road and challenge other gangs to all sorts of matches. The gangs had no parents to organize them in those days it was strictly do it yourself and make any equipment out of odds and ends. I used to tag along with my elder brothers, Stan was 8 years older and Colin was 6 years older. I remember one group outing, because most swimming pools were closed for the duration, we went to swim/paddle in local rivers. On this occasion, we climbed over a farm fence out in the countryside about 2 km from home, to gain access and walk along the bank of a waterway called the New River, this was a canal which supplied fresh water into London. We reached a place, now roughly where the river crosses over the M25 Motorway, and proceeded to get undressed, down to our underpants Just then the air raid sirens wailed and we saw coming towards us from an easterly direction, low over Waltham Cross a single Heinkel Bomber that was machine gunning anything that moved across it’s track. The anti- aircraft guns were returning fire from all directions and we could see the shells bursting all around this aircraft. Then we realized that if it continued on this course, we would be underneath a lot of very hot, sharp, deadly shrapnel from these shell bursts. But as it reached about 1 km from us, we were about to jump into and under the water, the plane turn back the way it had come, disappearing in the distance over Epping Forrest. I believe it was eventually shot down. Another incident with a street gang was a stone and stick fight against another gang. Being about the youngest in the gang, I was told to be the first-aider. I was given a small white cotton bag with a red cross marked on it, strung on a piece of string to carry on my shoulder. It contained a handkerchief to use as a bandage and a bottle of water. The main ‘weapon’ was a catapult, made from a ‘Y’ shaped stick cut out from the hedgerow bushes, 5mm square rubber elastic band tired to the prongs and with leather cup, made from a tongue of an old leather boot fixed to the mid point of the rubber band. The missiles were small round stones. The other ‘weapon’ was a stick, probably part of an old broomstick about 30 cm long, sharpened to a point at both ends. This stick was thrown, at the opponents, end over end, like a boomerang. But in our case the fight never took place, probably some parent heard about it and stopped it.

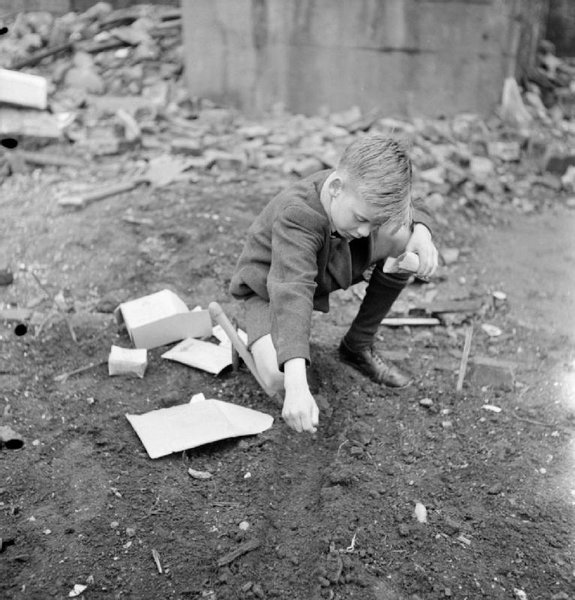

In 1944, where I lived came into range of the ‘doodlebug’ — German V1 pilot less aircraft bombs. These weapons were probably aimed at the small arms factory, but usually over or under shot their target, landing and exploding on the surrounding houses etc. The bombs, powered by a primitive jet engine, would drone across the sky and we were warned that they were harmless as long as we heard the engine running. But if the engine stopped you were advised to immediately take cover by lying face down on the ground, preferably in a slight depression and stay there until it was ‘all clear’. This was due to the fact that the bomb would glide down to explode at ground level, sending the blast outwards and upwards only. So if you were lying low, the blast would pass over you. This is what happened to me, I was running an errand, for my Mother, even though I was only 6 years old at the time, everybody had to share queuing for food, and was on my way home with a bag of groceries, when this doodlebug flew over, so I laid down in the gutter, with the kerb stone as protection, but it just flue on, so I got a ‘telling off’ from my Mum for getting soaking wet. Another tale about doodlebugs was, when one came down near our home, in Homewood Road. Late afternoon, I was playing with my younger sister and baby brother in the ‘living room’, my Mum was talking to a neighbour, when this doodlebug flew over, the air raid siren may or may not have sounded, they appeared and disappeared so quickly that there was not time for the alarm to operate, when the engine cut out. Us, children dived under the heavy wooden dining table, as was the practice in those times, closely followed by our large rotund lady neighbour. My siblings and I went sent sprawling out the sides, and the neighbour was stuck under the body of the table with her backside sticking out. The bomb exploded, but though the roof of our house was blown off, we survived unharmed and the neighbour beat an undignified retreat! The devastation from the resulting explosion was extensive; every house within 500 metre radius was flattened to the ground. I do not remember if there were any casualties, but recall that the emergency services cordoned off the area and barred everybody from entering until declared safe. The next day, a friend and I went down a back alley to see the damage and, as was the then custom of little boys, try to obtain trophies, like bits of doodlebug or shrapnel, but the whole bombsite was guarded by army soldiers.

By the end of the war, I had a box full of shrapnel, busted steel fragments of anti aircraft shells, but it disappeared, probably in one of my Mother’s clearout sessions.

War time for a child was scary at first, but as time went on, you accepted the situation and carried on with the hope that nothing would happen to you put to the back of your mind. At the end of the war, everything outside the home was unkept, unpainted and dirty. There was no one cleaning the roads, no one painting and decorating, the only paint available was for camouflage or blacking out. The grime was every where. In every road in Enfield there was a bomb site, with gaps in the houses, like broken teeth. I remember the blast walls built around door entrances, sand bags and concrete blocks for stopping tanks lining the roads and bricked up empty shops.

These are some of my boyhood memories of those times ….

Contributed originally by Holywood Arches Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by A Scott of the Belfast Education & Library Board / Holywood Arches Library On behalf of Edward Cadden [ the author ] and has been added to the site with his permission.

The author fully understands the sites terms and conditions.

Preparation for War

My father was born in June 1902 and named Edward after the newly crowned King.

He joined the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Irish Rifles in 1921 and the Battalion was posted overseas. They sat in the troopship in Golden Horn Straits for 2 weeks waiting for politicians to decide whether to invade Turkey following Kemal Pasha’s expulsion of Greek occupation troops.

Then to Egypt for 2 years in support of the civil power with a successful spell of ceremonial duties at the coronation of King Faud.

To Poona in India where in 1927 the regiment became the Royal Ulster Rifles and with full military honours a coffin containing R.I.R. rubber stamps, headed paper and shoulder badges was laid to rest in Wellington Barracks with a headstone inscribed R.I.R. R.I.P. R.U.R.

A short leave to Belfast in 1928 were he married my mother Jane and my sister Jean was born in Poona in December 1929.

After an unpleasant stint in steamy Madras the Battalion sailed for home in 1932 but the men were disembarked in the Sudan to prevent Mussolini extending his ambitions after conquest of Abyssinia. The enforced tour lasted to 1934. Just over 2 years in the UK at Catterick and the Isle of Wight then off to Palestine in 1937 for active service against the ancestors of the 21st Century Palestine Freedom Fighters.

In the 16th Infantry Brigade under the command of Brigadier Bernard Law Montgomery the Battalion developed novel tactics in Galilee of highly mobile ground forces with close air support by RAF units commanded by Group Captain Arthur Harris all this was relevant to World War 2 for without the long tempering of experience for officers, N.C.O.S. and senior riflemen the unit could not have stood up to the campaigning of that war. On return to the UK in 1939 it was clear that war with Germany was coming and a massive refit was landed on the unit with my Dad as R.Q.M.S. (Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant) and experienced weapons instructor in the midst of it. The personal uniform and equipment which had remained virtually unchanged since 1908, with the addition of a steel helmet and gas respirator in WW1, was all changed. In came the short blouse battledress and a new pattern of webbing equipment.

Many new vehicles were added to the unit’s equipment including tracked Bren-gun carriers. New wireless equipment required new specialists and new operational methods. The light machine gun — the Lewis was replaced with a Czech weapon for which Enfield had got a production licence just before Hitler added the rest of Czechoslovakia to the Sudetenland.

The BRNO-Enfield — the Bren arrived in quantity but without instruction manuals. It was entirely different to the Lewis so Dad and other instructors had to teach themselves how it worked by rule of thumb and experience. A rather useless anti-tank weapon appeared also - the Boyes rifle. Supported by a bipod this had a magazine of 5 half-inch calibre steel bullets which in theory would penetrate a tank’s armour and ricochet around inside causing havoc to the crew.

Experienced men were posted off to help form new units and replacements had to be trained from scratch. Dad at one stage had to teach the laying of barbed wire entanglements with balls of twine bought in Woolworth.

The Phoney War

The newly promoted Major General Montgomery managed to get most of the units from his 16 infantry brigade incorporated in his new command — 3rd Division. The main defensive problem was spotted as soon as the division arrived in France. The gap from the end of the Maginot Line to the coast along the Belgian border the Rifles were based in Tourcoing and like the rest of the Division busied themselves with training and with construction of prepared positions of trenches, sangars, barbed wire and mines to oppose any advance from Belgium.

My Dad’s hard work was lightened (I hope) by my birth on 7 January 1940 in Belfast. Their commander’s puritanical, even Cromwellian style of command led to 3rd Division’s proudly borne nickname of “Monties Ironsides” my dad received leave to inspect his new son in late spring and headed back to France just in time for the German offensive.

Just before the crucial moment Montgomery was moved off to command a new division and hand-over take-over added to the confusion.

The rapid collapse of Dutch and Belgian armed forces caused the Division to be moved out of the prepared positions and rushed forward to hold the Eastern border of Belgium. The German tactics were on a much grander scale those practiced by 16 Infantry Brigade in Palestine. Before fresh troops could replace 3rd Division the German armour punched through Tourcoing and did not stop before reaching Bayonne and a French surrender. The rifles and their Scots and other comrades found themselves not part of a coordinated defence but a lonely rearguard to slow the Germans and permit evacuation of the B.E.F. from Dunkirk and adjacent areas.

R.U.R. were defending Louvain, or more properly since it is a Flemish area Leuven.

Fortunately German armour was engaged elsewhere but the infantry fighting was fierce. At one stage opposite platforms of the railway terminal were occupied by Germans and by the Rifles. An enterprising Bren-gunner to make the Germans believe defence was heavier would fire a magazine then run along the pedestrian subway and fire a second magazine.

Ammunition ran low and at nightfall Dad set off with transport to fetch supplies from the rear depot. Arriving there he found R.Q.M.S.’s from other units in frustration because the depot had decamped. Dad asked an impolite major where supplies could be found and was told the coast. A conference with the other unit reps. and Dad decided to lead a dash to the coast. The major butted in to remark that it was thought the Germans had cut the road to the coast. “How can we get there?” asked Dad “fight your way through” snapped the major Dad thought this comic as his detachment had one Bren and an anti-tank rifle with only 2 rounds of armour piercing. However Dad and the Rifles in the lead they reached the coast overloaded with ammo and headed back. The ammunition was delivered safely to Leuven and some years later Dad found one of the W.O.s who had followed his lead from another unit had got a M.B.E. for the effort. The Rifles regarded such action as Dad’s as par for the course in their outfit.

It became clear that the holding action might result in the destruction of the Battalion so Dad was given a party of specialists and long-service N.C.O.s essential to the creation of new unit and told to get them to G.B..

They reached the beaches at Bray dunes near Dunkirk where some troops had abandoned their personal weapons and 40mm Bofors anti-aircraft guns sat unmanned. Dad got every rifleman to collect a second rifle and the Bren-gunner to pick up a second Bren. He acquired a service Smith and Wesson revolver which he had for the rest of the war.

They were lifted off safely by the Ramsgate Lifeboat with their feet dry and taken to a “Sword” class destroyer off-shore which took them to England.

The 2nd R.U.R. was not destroyed but with other units of 3 Division fought back to the coast and were evacuated depleted but unbroken.

Becoming a Gentleman by Royal Commission

Montgomery instead of taking a break came back and assisted with the resurrection his “Ironsides” and then headed off to a new command.

Apart from replacement of equipment lost in Belgium some new items arrived including some Thompson sub machine guns from the U.S.A.. Efforts had to be made to create command structures and defensive positions to deal with the anticipated invasion. Dad got some leave to visit us in Belfast but was kept busy through late summer and early autumn.

Then he was commissioned as a Lieutenant. A W.O.I. when commissioned skipped 2nd lieutenant otherwise he would be paid less than his existing grade when promoted.

A course at O.T.U. to teach Dad techniques of command, traditions and military law and manners of which he knew more than his instructors.

His first posting was as Lieutenant Quartermaster to a training depot for the Auxiliary Territorial Service, the predecessor of the Womens Royal Army Corps. These young women did not go into the front-line like their 21st century descendants but did mechanical, signalling and admin tasks to free up men for front-line service.

We joined him in the depot’s base town Dorchester in an underoccupied home requisitioned in part as married quarters in 1942 we experienced our first bombing as a united family.

London

When we arrived in late 1942 at our requisitioned quarters in Edgware shared with the Jewish owners, the Roes, the great blitz was in a lull. The Luftwaffe needed all the bombers it could get in Russia and the North African campaigns called for even more. The pattern was isolated “nuisance raids” by high altitude bombers or low-level sorties on the south-east by single or handfuls of fighter-bombers. The RAF as well as night-raids by heavy bombers was attacking targets in France and the Low Countries by day with fighters and light bombers. The USAAC was also testing the water with increasing strength there were municipal air raid shelters, the tube doubled as an air raid shelter and schools had mass shelters for pupils homeowners could get two types of prefab shelter. The Morrison for use in a well braced indoor area or the Anderson to be inserted in a hole in the garden. Surplus Andersons became coal-houses for post war prefab houses Dad was promoted captain and posted as Q.M. of the London Irish Rifles. This was a T.A. Battalion affiliated to the R.U.R. and drawing recruits from expatriates living in London. It like other T.A. units was supposed to provide an immediate war reserve for regular units. Over 3 years of war and the London Irish had not been got into action. My Dad and a batch of “old sweat” N.C.O.s and officers were posted in to give a kick start.

The main trouble was the shared experiences of members of the regular units with hard oversea postings and awkward operational contexts did not apply to the re-cycled civilians of the T.A.. There was no espirit de corps. One sample may illustrate the symptoms of a general malaise. On a kit inspection Dad found that a “rifleman” had sold off all negotiable items of his personal kit. Worn-out uniform items were commonly used as cleaning materials or waste containers. The miscreant presented a plausible assembly of spare clothing made from washed and ironed cleaning rags and cardboard. He had sold all the brass fittings for scrap and substituted dummies made of tin foil.

The Battalion got sorted out and was lined up for service in North Africa. Near departure a company commander developed an illness diagnosed as Plumbum Ostillendum. My Dad was about to be made Acting Company Commander and posted out when the authorising office pointed out that he was past the age-limit for active front-line service. Despite the false starts the unit stood the horrid pace well in North Africa and Italy.

Top Secret

Mum, my sister and I were posted back to Belfast when the London Irish Rifles departed because Dad was posted as a Q.M. of a secret base at Westward Ho near Bideford in Devon — the combined operations experimental establishment. The beaches there were similar to those in Normandy and tidal conditions, sea-levels and cliff features were also similar. A mixture of technical experts from all 3 services was gathered there with representation of the U.S.A. and other allies.

Much of the supply of specialised landing craft was tied up in the U.S. Pacific campaigns. The intended stockpile for Normandy was to be further depleted for landings in Italy.

Devices experimented with at Westward Ho were amphibious versions of Sherman and Churchill tanks, rocket firing landing craft, a DUKW amphibious lorry fitted with a fire brigade extending ladder to scale shoreline cliffs. A total disaster (fortunately without causalities) a huge rocket propelled wheel to explode minefields. The rockets fired out of sequence, the brute tipped over and proceeded to whirl towards the rapidly scattering spectators.

More mundane but successful machines were amphibious cable layers, Bailey Bridge carriers and bulldozers. A scale trial was made along the coast of the Mulberry Harbour. One of Dad’s missions involved a flight in an R.A.F. Proctor liaison aircraft from Chivenor to Pembrey to check the functioning of a trial laying of P.L.U.T.O. the pipeline under the ocean. This in full scale service would pump fuel from England to Normandy. The Q.M. of such a unit had to find often at short notice a myriad of components — some of them in no military inventory.

One of the engineering experts was Lieutenant Commander Neville Shute Norway. He had created the Airspeed Aircraft Company which had supplied the King’s flight with its first aircraft. The company’s Oxford twin engined trainer was one of the mainstays of R.A.F. wartime training systems, his company had been taken over by De Havilland. He was an author of Novels already by 1944 using his first two names Neville Shute. In a famous post-war novel “No Highway” he foreshadowed the Comet Airliner disasters with a fictional airliner plagued by metal fatigue. The inventiveness of the elite personnel was shown in more mundane ways. Childrens toys were almost unobtainable in 1944 and my Dad’s sergeant produced toys from scrap packaging and other materials.

I received a model of the French Battleship “Richelieu” usable on a wheeled frame or to float in the bath. There was a model also of a seep, and amphibious jeep and a long-lived Sherman tank model. Scrap packaging celluloid, .303 rifle chargers, washers and tail ends of brass and iron rods were incorporated and painting came from the dregs of paint left from finishing touches to the amphibious equipment.

A major pre D-Day disaster happened near the combined operations experimental establishment at Westward Ho when US troops practising amphibious landings were intercepted by E-Boats and suffered heavy causalities. The unit did not close with the success of D-Day for many rivers needed to be crossed before V.E. Day and Seaborne and Riverborne operations were necessary in the Far East.

With war’s end Dad decided that our family had been separated too often and a peacetime career even as a major would not help the development of a teenage daughter and a six year old son with postings to foreign parts. He decided to retire, take his pension and supplement it with a civilian job.

In 1946 a special job centre was established in Belfast for demobilising servicemen. Dad was delighted to find his neighbour in the queue was an N.C.O. who had served under his command. They chatted of times gone by and recent developments until they reached the parting of the ways. One lane was signed “Officers’ Posts” and the other “Other Ranks’ Posts”. They both emerged from their respective lanes as temporary Clerical Assistants Grade II in the N.I. Civil Service.

ADDENDUM

The Rifleman

Regardless of any rank he may achieve subsequently a Rifleman is always a Rifleman. He is part of an elite unit who taught the rest of the army how to make war. His full dress uniform is dark green and his badges and buttons are black. He marches at 120 paces a minute and does not change gear going up hill. Regardless of drill practices by mere infantry with whatever firearm is current a rifleman shoulders arms never slopes arms and he marches past with the weapon at the trail.

No matter what other units call it a Rifleman’s bayonet is a sword and he fixes swords and never fixes bayonets. He must never be mistaken for a Light Infantry man who is merely a copy of the French Tirailleurs. Each Rifleman is an individual fighting unit which will operate on its own whether support is near or not. Before commandos, parachute regiments or S.A.S. the Rifleman had broken away from the lumpen proletariat of infantry of the line.

Indeed in the Royal Ulster Rifles one Battalion went into action on D-Day as airborne troops and the other on foot in traditional style.

In ceremonial Rifles have no colours their battle honours are on the drums of the band. When the band displaying old sweats may be singing sotto voce

“You may talk about your Queen’s Guards

Scots greys and all

You may talk about your kilties and the

forty second TWA

But of all the world’s great heroes

under the Queen’s command

the Royal Ulster Rifles are the

terror of the Land!”

“Quis Seperabit” the motto of the Knights of St Patrick is completed in original by “From the Love of God”. For a rifleman the unwritten follow on is “From love of my regiment.”

Contributed originally by Julian Barrett (BBC WW2 People's War)

As I was only 3 at the outbreak in September 1939 my strongest memories are of the latter stages of the war.

So I have no recollection of September 3 even though I have two memories from earlier: one was to do with a visit to the seaside, but the other was relevant to this account because we visited relations in Southampton over a Bank Holiday (probably Easter '39) and my father and a couple of cousins were playing around with the wireless. They stumbled across a foreign station which was probably German and I recall being petrified and bawling the place down. Which shows the effect of propaganda on even the young: I had no idea of who these 'Germans' were other than that I had good reason to be frightened of them.

Later I learned that on the morning of 3 September, my mother was returning from church when the air raid siren went following Chamberlain's broadcast announcing the declaration of war. Apparently she was about a quarter of a mile from home and by her own account ran in a panic faster than she had ever done before or subsequently.

We lived in Edmonton, North London, and though this was not directly in line of air attack we were sufficiently close to Lea Valley industry and the East End for me to have a recollection of the Blitz. I remember being woken night after night and carried by my father to a neighbour's Anderson shelter, with constant noise from the bombs and ack-ack guns (there was a battery nearby on the pre-war Saracens' rugby ground), while the dark sky was pierced by the searchlight beams.

This was comparatively early in the war so this shelter was just that, a hole in the ground covered over with corrugated sheeting and earth, with a cold, damp and gloomy atmosphere. Later I would occasionally stay a night or two with my great-aunt and uncle who lived a mile away and by then they had installed bunks with some bedding and had tried to create a little comfort with a small rug and a drape over the entrance such that these visits were quite an adventure for a small boy.

In 1941 the bombing continued but was not as intense, and it was time to start school. There would be occasional daytime scares but I cannot recall my trips to or stay in school being severely disrupted by air raids. My abiding memory is of the long tedious walk generally accompanied by a cousin (my mother had had a second son the previous year and was pregnant again) to the convent in Palmers Green, I was not a happy walker at this time.

Shortly before that, however, there had been a family crisis the full measure of which I only learned many years later. I had an ear infection which would not clear up and which puzzled our family doctor. Eventually he sent me to the North Middlesex Hospital where I was given M&B (I believe), the seemingly magic cure-all of the time and kept in a room at the end of a large ward away from all other patients, my parents were not allowed in the room, they could only wave through the glass partition from several yards away. Although I was in a half-drugged state it was very frightening but probably not exceptional for that time. What was different in wartime was that staffing in hospitals was difficult, and not all nurses in civilian establishments were of a high calibre.

On one occasion I had wet the bed and the Matron (or Sister, I did not know which) called me all the names under the sun and gave me a thorough verbal going-over. After 7 or 8 days of this, apparently my parents were informed that I had 24 hours to live which must have been acutely distressing for them.

However, that same night I coughed with an unusual sound. I had suppressed whooping cough and after this I was moved to a children's ward, stayed another couple of days, went home and the infection took its course.

My life took on a steady routine as it did for many others as the air raids receded. In late '42 we moved to a rented house in Southgate, the owner having moved out to live with his mother in the safety of the country for the duration of the war. I continued to travel to school in Palmers Green but now by bus, usually on my own, though friends would join en route. Nothing out of the ordinary then, but almost unimaginable for a 6-year old today.

My main memory of the buses was of many lady conductors, still something of a novelty then, and the restricted view from the windows: there was a small clear diamond only, the rest of the glass being covered with a tough gauze to minimize shattering from bomb blast.

As in hospitals, so in schools staffing was difficult and the quality was patchy to say the least. In spite of this, in spite of the fact that there were some teachers who were fishes out of water, I and many like me were taught by some wonderful people who, having known better times pre-war, could not have found life easy and yet they were able to impart a love of learning and school in general.

In my case I made great strides and eventually at the age of 7 went on to the Preparatory section of a grammar school in Finchley, mostly with 9-year olds and remained the ‘baby’ for another 6 years. This pushing of children into older groupings was not unusual at that time.

At the ‘big’ school we developed a bravado, such that when an occasional air raid siren went off we had the option of making for the (brick) shelters in the grounds or staying in the classroom, and mostly we stayed put.

In 1944 came the pilotless flying V-bombs and I remember the papers being full of the awe which greeted these ‘robots’, just the sort of dirty trick you would expect the dastardly Germans to get up to. Certainly their spluttering low engine note was scary but no more so than the eerie silence which followed the engine cut-out and which meant they were falling from the sky and about to explode.

This was something we experienced at first hand on 1 July 1944.

It was a Saturday and my mother had done her shopping in the morning, but, when she returned, she thought the meat she had bought with precious ration coupons was ‘off’.

My father who had volunteered for the army in ’39 but was rejected as not being fit. had kidney problems which always gave him considerable back trouble and after two spells in hospital, in ’43 he had one removed. This was an almost life-threatening operation at this time and he took a long time to recover. However, he was a clerk in the old Covent Garden fruit and veg market and, on this Saturday, returned from work around lunchtime as was customary in most jobs. After dinner, as we called it then, my mother went back to the butchers. I and my brothers were playing in the garden, Dad was clearing up in the kitchen. The air raid siren sounded and shortly after we could hear a ‘buzz-bomb’ drone. Dad called us in, my younger brothers obeyed, I being of the very advanced age of eight, wanted to carry on playing, nothing had happened before, so why should it happen now?. There was a knock on the front door, it was my mother hurrying back. Dad rushed to the front to let my mother in, usually the man of the house was the only person in possession of a key, then returned to the back and almost dragged me inside bodily. Mum scrambled under the kitchen table together with my small brothers. I can still see her swagger coat spread out over the floor and her hugging the deep wicker shopping basket.

Still in arrogant mode I refused to join the babies. Our house was quite modern then, John Laing 1935 construction, with a lot of long rectangular glass panes in what were then innovative Crittall metal frames. The bomb’s engine stopped. Dad had his back to one of these windows by the sink, facing me and with a hand on my shoulder as a sort of protection. He said: ‘this is one of ours’, and seconds later there was a fearful explosion, together with a the clatter of glass, tiles, and falling masonry.

My earlier cockiness vanished in an instant. My young mind could not comprehend everything and I was convinced the bomb had landed directly on our house and was working its way downstairs and would explode again. With all 3 children crying in fear, Dad led us through the debris. The front door where Mum had been standing just a minute or two earlier was blown off its hinges, and we emerged into the street where already neighbours had gathered. We were led down the road to a friendly cup of tea but Dad, we learned later, had glass splinters in his back, still not fully healed from his two previous operations, and he passed out when he reached the street. And all in the cause of shielding me.

We lived on one corner of a crossroads, and the bomb had fallen on the diagonally opposite corner, demolishing a large three-story building of flats in which another family of five were all killed.

We went to stay with my grandmother in Edmonton for a few weeks. In the meantime, the windows were covered up, the roof had tarpaulin thrown over it, the door was re-hung. Then a government official inspected the damage, pronounced the house as unfit and in need of demolition. There being a shortage of labour to carry out this work it could not be done immediately. Which was just as well. My father and the owner contested this decision and 60 years later the house remains repaired and intact, which says something about wartime conditions as well as about bureaucracy at any time.

A few weeks later, with the horse having bolted, Dad decided to close the stable door and applied for us to be evacuated. This time mothers were allowed to accompany their children, in contrast to the difficulties at the beginning of the war when children had to be sent away without their parents.

Early on a Sunday morning late in August we trooped off to New Southgate station, and stood for a very long time (probably around a couple of hours, good preparation for my later National Service) in a very long queue. A rumour went down the line that we were going to be shipped to Cromer. Now I had no idea where or what Cromer was, and Mum’s grasp of English geography, after a sheltered upbringing in the West of Ireland was shaky to say the least. I had been learning Latin for a year by this time and ‘Cromer’ had a foreign sound to it. But that was a puzzle, why would we be going abroad, surely that was not allowed unless you were in the services?

The rumour persisted and it became clear this strange place was on the coast somewhere. At which I badgered Mum for us to go back and fetch my bucket and spade, which she made clear in no uncertain terms was not going to be allowed by the man (or men) in charge. How this rumour took root I shall never know. It was difficult enough with all the coastal defences for locals to gain access to towns by the sea never mind a gaggle of refugees from V-bombs.

Anyway, eventually we boarded a train which made a stately progress north and I remember seeing the brickworks which I was told were in Peterborough and I also remember the vast railway yards at Doncaster. I kept asking when we were going to be in Cromer, and not getting a satisfactory answer. Eventually we pulled into Leeds Central and were bussed out to Bramley, where we were gathered in a hall. Here the kind ladies of the WVS (as it then was) arranged cups of tea and allocated billeting with various volunteer householders.

The numbers kept shrinking as one after another family was fixed up until we were the only ones left. Apparently almost all the others were in groups of 3 at most whereas we were 4 and finding room for 3 children was proving near to impossible. In the end the organising lady, a Mrs Fieldhouse, a very natural Yorkshire soul took us in and for the next 10 weeks we all slept in the same room.

This period was relatively uneventful. I was intrigued by the fact that the back doors looked out onto the street where the washing was hung, whereas the front doors looked out over small gardens and wasteland. I made friends with local lads of my age and in general they were very welcoming of this rather reserved southerner.

When the school term was due to start I was told I would be going to the nearby ‘council’ school. This was almost exotic to my young ears, though I had a shock when the headmaster did not believe that I was 2 years ahead of most of my peers. However, he decided to give me the benefit of the doubt but said he would test me with some long division. I enjoyed arithmetic from the beginning and found a lot of fun in solving problems for many years after but on this occasion, I froze completely and I have no idea why. I was sure I detected a slight smile of satisfaction on the headmaster’s face at the comeuppance of this smarty-boots ‘intruder’. Whatever, I was placed amongst boys of my own age and became very bored as I was going over things I had left behind long since.

In due course, Mum couldn’t cope with being cooped up in one room in someone else’s house and eventually persuaded Dad to bring us home. The house was habitable, Dad had requisitioned a Morrison shelter which went into the dining room and while the end of the war was not certain it was nevertheless in prospect.

From my point of view evacuation had been a big adventure. Trips to Roundhay Park on the trams were a treat, the accents were fascinating to my southern ears, and I had been indulged by Mrs Fieldhouse and her friends and family, though it was another 30-odd years before I visited Cromer for the first time!

Along the way one memory stands out: one Saturday morning I barged into the kitchen only to be quickly ushered away. However, I had heard enough to understand that the husband of a friend of one of MrsFieldhouse’s daughters had been killed and I heard the word ‘Arnhem’. It meant nothing then but many years later I learned bout the fate of many Yorkshire Light Infantrymen at that failed bridgehead.

The remaining months of the war passed relatively quietly as far as I was concerned, though certain things stay in the mind: asking my Dad what would be in the newspapers in peacetime when there was no war to report, seeing him bring home his ‘cotchel’ every week; ambling home from school one day with a clear sky overhead and seeing a V-2 rocket blown up in mid-air a few miles away (which turned out to have been over Barratts sweet factory at Wood Green). seeing my aunt’s grief on learning that her Canadian airman boyfriend had been killed in a raid over Germany.

However, I suppose my time during the war was really characterised mostly by ordinariness and a little bit of luck. Two events afterwards, however, made a big impression.

The first was on the morning of Christmas Day ’45, Germany had surrendered in May and Japan had thrown in the towel in August. I usually walked to the church at Cockfosters where I had become an altar-server and would often be joined by one or other of the lads who lived nearby. We were down for the 11.30 Mass and as we emerged onto Bramley Road a small squad of German POWs was being marched in the same direction. They came from a camp which had been set up just off Cat Hill. We tried to keep in step but they were too quick for us. A few minutes later we arrived at the church and discovered that these prisoners were also at the Mass. This was a surprise, after all, weren’t these the agents of the devil as we had been led to believe? They were seated at the back under guard. Later during the distribution of communion they stood up and gave the most beautiful and moving rendition of Silent Night (in German, naturally) I had ever heard or have heard since. Here was a group of men we had been told to hate and yet even to my young and inexperienced ears they had presented something exquisite. I was not into any philosophical thoughts at the time but gradually down the years it taught me a lesson about the utter waste and futility of war, that we are all human beings, and all of the same race.

The second event happened a couple of years or so after the end of the war. The radio was on and a play was about to start on the Home Service. The opening sequence included an air raid siren. I was only half-listening but immediately I was riveted to the spot and broke out in a sweat of fear.

A sound about which we had become almost complacent through the war clearly had had a much deeper effect than we knew.

Contributed originally by eric heathfield (BBC WW2 People's War)

As I said previously after May 1941 enemy activity diminished considerably, we had a few raids usually around xmas time or just after.Also a few fighter bomber daylight raids in 1943/4. Then in the early part of 1944 the germans made a series of rather heavy raids. They dropped what were known at the time as oil bombs. These did a great deal of damage, I remember one fell on Priors dept store near the Tally ho North Finchley this was a modern concrete building it was completely destroyed apart from the steel girder frame work!There was very little damage locally although I think it was around this time that a large bomb fell on Cat hill East Barnet demolishing several houses. One point i will make we always knew when a raid was coming because the BBC would stop broacasting when a raid was imminent so that the enemy could not use them as a method of navigation and take bearings from them.When the radio went dead we would move into our morrrison shelter and put up the wire screens. Then later would come the gut wrenching sound of the sirens.These raids in 1944 cost the enemy heavy casualties and as the nights shortened they stopped.Then on the 6th June 1944 I was woken early in the morning by the sound of many aircraft flying over.We were used to seeing American flying fortresses in large formations most days but it was too early for them as they always flew over during assembly at school.I got out of bed and went to the window which had a good view of the sky to the east.I had heard people say the sky was black with planes but this day it really was hundreds of planes towing gliders and squadron upon squadron of Boston and Marauder light bombers all heading east!Also Spitfire squadrons were airbourne to all planes had white stripes round the fuselage to identify them as allied aircraft. This was D day!When we listened to the 8 o'clock news the landings were announced.THe next few days were euphoric we were all excited and the standing joke repeated ad nauseum was " Do you know where the landing is- at the top of the stairs" very corny by the 3rd day! Then in the following week on the thursday night we found that "Jerry" had a nasty joke of his own up his sleeve! Went to bed about 9-30 as usual when it was school tomorrow. Then about 1 am the sirens sounde and I made my sleepy way down to the dining room and the morrison shelter.It was soon evident this was a heavy raid constant gunfire and low flying aircraft and machine gun fire. This continued for about 2 hours then all was quiet,the all clear didnt sound but aftre a while Dad said we might as well go back to bed its over! The following morning I went to school as usual and asked my friends if they had heard the all clear?None of them had -very strange then later in the day we were all made to go down to the cloakrooms which served as a shelter the ceiling being strengthened with beams and the windows covered with sandbags.When we were sent home at noon we heard that this was hitlers secre weapon a pilotless aircraft packed with a ton of explosives.These kept coming over for the next 3 months at odd intervals.The next day which was a Saturday I went with my dad to chesthunt Resouvoir for a days fishing it was very civilised there we had a small hut where we could cook and sahelter from the weather and could even sleep there as we had 2 naval hammocks slung.It was a rather dull overcast day,we heard a few flying bombs in the distance, suddenly I heard a strange sound unlike any other aircraft noise I ha ever heard I was by this time as most of my friends were an expert areoplane spotter. Then suddenly there it wa at about 500 feet flying west a Gloster Meteor thogh of course I didn't know that at the time although the radio had reported about jet aircraft about a week earlier.A wonderful sight ! Well as I said the attacks continued,one night a V1 fell in Grange Ave East Barnet in the next road to my sister Grace.I dont think anyone was killed. Then one lunchtime at school I was in the wash room in the cloakrooms when we heard a V1 coming Mr Zissell our headmaster rushed in from the playground roarinng "Everyone down on the floor" we didn't need telling twicethe bomb slid over the school down church hill rd clipped the flagstaff on St marys Church and exploded in Oakhill park near the bridge near Rushdene ave luckily not killing anyone! Some of my friends from the East barnet grammer school had a narrow squeak as they were in the park at the point of impact but saw it coming and just made into a surface shelter they were badley shaken but unhurt. Then in late august we had our worst tradegy of the war. I did not witness this personally as we had gone away for a couple of weeks fishing in Dorset as was my fathers custom whenever he could snatch a few days away from the Times I think this helped to keep him sane! these were stressful times as they were not only publishing theTimes but also the American paper The Stars and Stripes for the troops.Anyway on or about the 21st August about 7-45 in the morning the Standard telephone factory which was about 200 yds from the end of our street was hit by a flying bomb causing horrendous casualties in fact the highest ever casualties in a single incident.several hundred dead and many many severely injured . One young girl aged about 15 in her firsat week at work lost both legs,luckily she made a full recovery and 11 years later was in victoria maternity hospital having a baby at the same time as my late wife.Ou house had all the windows blown out and the ceilings down.The last flying bommmb to land near us was sometime in the autumn, it was my most scary moment of my 71 years! We were in the morrison because the bombs came at any time it was after midnight because Dad had come home from the office.Something woke me and I heard the bomb coming then suddenly the engine cut! When that happened your heart stood still and you could hear a pin drop.Then to my utter horror I heard a sound it was the sound of the V1 gliding! I could literally hear the air over the flying surfaces Dad swore then came the explosion the solid steel shelter lifted with the blast.The bomb had landed further up the hill in Russell Road causing several deaths including a friend of my mothers and her twin sons aged about 13.This was the last f lying bommb in the district.In September 44 one saturday morning I was lying in bed just having woken up when there was a tremendous explosion followed by what sounded like a roll of thunderwe were to get to know that sound all too well over the next few months hitlers second secret weapon was up and running the V2 rocket hurtling in at supersonic speed devastating wherever it hit. This one was at Bounds Green many of these landed in London and you could hear them for miles the only other one in our area was at New Barnet killing several people and burying others for a couple of days (this was always one of my worst nightmares the thought of being buried alive)One poor chap held a beam up over his Brother but sadly his brother was dead, later he lost his mind and used to wander the streets shouting and talking to hiself the children in later years used to make fun of him not knowing his story unless someone told them.Personally the V2's worried me less than aircraft attacks which always seemed directly aimed at one or flying bombs which were nerve wracking.With the v2 if you heard it go off you were alive and that was that,I am sad to say we were mostly pretty callous by this time well you had to grow a hard shell or you wouldn't have been able to stand it!Well by March 45 the raids and rockets peterd out then suddenly it was all over I was then nearly 13 going on 30.Would like to say a couple of final things clear up a couple of myths.Firstly despite many documentary 's Londoners on the whole did NOT shelter in the underground in fact people who did were rather despised, any way they were not very safe as was the case at Bounds green station when a bomb penetrated to the platform ripped all the tiles from the walls killing a number of Poles who used it to shelter.Most people had there Morrisons and Anderson shelters and prefered to take their chance above ground.Also I get very angry when i hear people talking about soft southeners as we were bombed throughout the war not just a few nights as were plymouth and southhampton the blitz lasted from Sept7 40 to May 10th 41 almost every night so I don't think we were soft If you would like any more information please don't hesitate to ask.How ever I am suffering from Chronic renal failure at the moment so if you want to know anything better ask soon All the best Eric Heathfield

Contributed originally by whprice2005 (BBC WW2 People's War)

‘CORNCOB’ MS INNERTON & HMS DESPATCH

IN ‘THE FLOATING’ MULBERRY HARBOUR

by

William Henry Price (Army No 2054978 b24/7/1914)

In 1928 I left school and spent most of my early working life in the music instrument industry. In April 1938 I joined the Territorial Army, whose headquarters were in White City, Shepards Bush. Europe at that time, was uneasy as Germany was preparing for war. In September 1938 the Territorial Army were mobilised in the event of war. A lot of the equipment that was from the 1914-18 war, a lot of this was obsolete, especially in my own unit. The September crisis as it was called, instigated the Prime Minister of the day, Neville Chamberlain, to visit Hitler in Germany. On his return from Germany he claimed Germany would not go to war with Britain, upon a signed agreement. This agreement claimed peace in our time.

During this period my unit, amongst other TA’s were called out in the event of war

Some people didn't believe this as Britain wasn't ready for war. Although it did give us a breathing space, as we knew war would come eventually. We were totally unprepared. As an example, having been called out in the event of war, I spent 3 nights sleeping on a London bus. No one knew where we would be stationed. Eventually we were given a site in North East London, where I spent a further seven days until the September crisis was over. My employer was compelled to release us, for the crisis. I was the only volunteer for the Territorial Army in our company, they were completely unaware of my activity. I was given a hero's welcome on my return. The directors had been in the 1914-18 war and were pleased to know one of their employees had volunteered. In those days I was cycling 30 miles a day back and forth to work. When training two nights a week with the TA, I cycled an extra 5 miles a day from work. I was cycling a total of 190 miles a week.

The following year in 1939 ( a week before the war started) I was called out again, as Britain knew there was going to be a war. For the first 18 months of the war I was stationed in the London area which included the Blitz. I was very fortunate in not having been posted to Dunkirk.

Around 1940 I was moved from West London to the civil service sports ground near Barnes Bridge, at the side of the river Thames. We were able to use the cricket equipment, and whilst playing I received a direct hit by the cricket ball on the leg. It was severe enough to warrant hospital treatment for about three weeks. My first contact with 'friendly fire'! After the first three weeks I was sent to Hammonsmith Hospital for x-rays, the medical officer decided to send me on seven days sick leave, to be followed by light duties, which meant me being sent to NE London. I was the troop clerk and also in charge of stores equipment for six anti aircraft sites, such as petrol etc. Whilst there, the troop Sargent WH Walverton, (from the 1914-18 War), received a letter from the Mayor of Southgate, whereas a local family wanted to adopt a soldier. He turned around to me and said "Here Price, this is ideal for you". Hence, I was able to visit them for a occasional meal, the family were a young couple with a new arrival. I had already been adopted by the local pub the Chaseside Tavern, and had been invited to join the family for Christmas lunch. This was my contribution to the early part of the war as 'light duties'. During the Blitz, crossing through London on my weekly 24 hour leave to Kent from Charring Cross I noticed people sleeping in the tube stations for safety, and many families living on the rail tube underground. These were being used as air raid shelters.

Late 1941 I volunteered for a new unit being formed which where originally the Fourth Battalion Queens. They were being converted to a light anti-aircraft regiment (bofor guns 40mm). After training we were semi mobile, and hence we moved to most parts of the United Kingdom. Twice the regiment was mobilised for overseas service, which never eventuated. We fortunately stayed in the United Kingdom.

In December 1942, I was stationed at West Bay Bridge Port, a message came from headquarters for me only, to be transferred to a gun site on the outskirts of Yeoville. This particular location was the rear of a country pub. One had to walk down the side of the pub to get to the gun site. At the time I was a number 4. My job on the gun was to fire it. I was named 'Trigger Joe', as I was considered quick on the draw. During an air raid an enemy plane was shot down. Hence the local people donated a radio set to the site. It was here one morning, I think it was New Year's eve, strolling along the side of the pub from the gun site, when a young WAAF came by with a bike and a large tea bucket. She approached me, to fill the bucket with beer from the pub. As it was awkward to take the beer back to the WAAF site at the bottom of the hill. I was asked to help with the beer transport, and as a result I found myself invited to join them at the head of their table at the Ballon Barrage site to drink the beer!.

Early 1944 the Colonel, informed me that the regiment had been allocated with a special job on the occasion of the invasion of Europe. In May 1944 my battery was moved to Oban Scotland, each person was issued with a hammock out in the bay with several merchant ships. I was allocated to one merchant ship called the Innerton. Little did we realise, it was to form the outer brake water called the Muberry Harbour. I gather this had been planned in the 1942 conference in Quebec by Churchill and Roosevelt. Towards the end of May 1944 a very large convoy of merchant ships made their way through the Irish Channel and were eventually joined by the American and British war ships of approximately 60 ships. Each of the merchant ships did have a bofor gun attachment on board. At that time we didn't know what was going to happen. As most people know D-Day was put off from the 5th to the 6th of June, and we continued to past the time until the 6th.

The convoy of merchant ships moved off on the afternoon of June 6th known as D-Day. There were approximately 17 merchant ships that started to move into position, known as block ships. They were to form the outer brake water for Mulberry B, this being the British and Canadian sector. The effect was to calm the seas inside their protection. The ship I was on was number seven in line to be sunk. From then on, other parts of the harbour started to arrive including concrete caisson blocks etc. It only took a few days for the harbour to take effect and be completed. During this time landings were being made on the beach. My regiment's duty was the defence of the Mulberry Harbour. I was transferred to a HMS Despatch which was the headquarter ship of the Mulberry Harbour, and I served there until the end of the Normandy campaign. Adetailed account is referenced from John de S. Winsers book The D-Day Ships Neptune: the Greatest Amphibious Operation in History:

A fleet of elderly or damaged ships were assembled to be sunk in shallow water off each of the five beach-heads, to provide shelter for the smaller craft. The first contingent moved in three convoys, codenamed 'Corncobs', with I and II reaching the French coast between 1200 and 1400 on the 7th and III, consisting of the oldest or slowest vessels, arriving one day later. The ships had a 10lb demolition minutes from the time of blowing the charges to the vessel settling on the bottom. The plan was for one ship to be scuttled or planted every 40 minutes. The ship's superstructure remained above the water-level enabling the accomodation to be utilised. The shelters were named 'Gooseberries' and numbered 1-5.

In the middle of June 1944 a violent storm wrecked the Amercian sector of the Mulberry Harbour. The

British sector was also partly wrecked, but repaired with parts of the American sector.

The Normandy campaign was over by the end of August 1944. HMS Despatch left for the UK, calling in Portsmouth where the port watch commenced their leave. I remained on ship until Devonport. On arrival I was given seven days leave, with instructions to return to France. It was there my Battery 439 (light anti-aircraft unit) was reformed and we made our way through the rest of France and Belgium and later a cold and wintery period in Holland.

As the war ended we were in Germany. For a period I was detailed with others to a displaced persons camp. There were approximately 900 displaced persons which included mostly Polish and people from the Baltic states, Estonians etc. I remained in Germany until November that year when I was demobed in November 1945.

Bill Price June 2004

Contributed originally by John Brownbridge (BBC WW2 People's War)

I'm 70 now, but there are things about the war I shall never forget. It's strange how the war could be so scary at times and yet there were times when it was so funny, or even exciting.

Air raid shelter

Our air raid shelter was down the bottom of the garden. It was really hard work digging the clay out to erect it. Our neighbours put theirs facing the wrong way and so they had to add a big pile of earth in front of it in case their house was hit and the debris fell right up against the entrance.