Bombs dropped in the borough of: Lambeth

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Lambeth:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 1,215

- Parachute Mine

- 2

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Lambeth

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

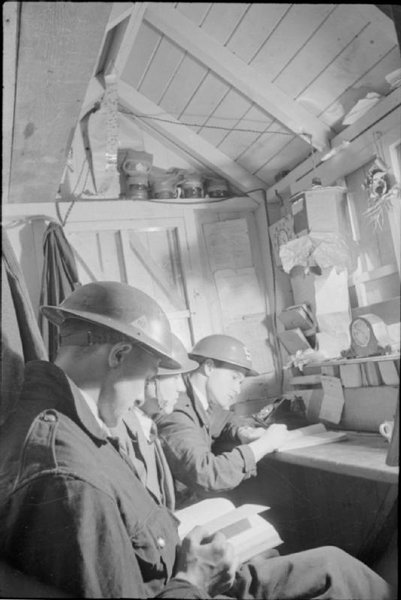

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by Pamela_Newbery (BBC WW2 People's War)

As I was only 3 years old when WW2 began, I have no memories of before the war. In about 1943 I was given a banana by a soldier on

leave from Africa, but I had no idea what it was or what to do with it. On being shown how to peel it, I then took half an hour to eat it, savouring every mouthful.

I wonder if the other local children who were also given a banana have similar memories.

These days bananas are so plentiful that younger people will not realise what aluxury they were in the 1940's.

On the rare ocassions when the greengrocer had a delivery of oranges, my mother would collect up the childrens' green ration books, walk half a mile to the shop and then join the queue to bring back some oranges.I probably stayed like a dog in the kennel in our Morrison shelter.

Contributed originally by Charles Nightingale (BBC WW2 People's War)

I was only one at the outbreak of war, one of four children born between 1935 and 1941. Memory starts with seeing my brother brought home after he was born in 1941, when I was just three. We lived in the road that led from Penge to Crystal Palace. At least four houses in it were flattened, and more than half including ours were damaged. I do not recall the collapse of our roof but was often told of my fathers dramatic trip up the stairs through a fog of powdered plaster, to rescue me: I was 'miraculously' lying in my cot surrounded by debris, yet unharmed. My mother has told me that one night at the height of the night-time blitz, she and my father abandoned hope, when the bombs seemed to be setting fire to the whole neighbourhood. They lay in each others arms waiting for the end with the sound of Armageddon in their ears. The sky, all around, was flickering red she said.

Mostly, though, we used to sit under the stairs wearing ghoulish Mickey Mouse gas-masks. My mother had Edward, my youngest brother inside a sort of capsule into which she used to pump air, whilst my father was fire watching. There were frequent air-raids which I enjoyed, because I was brought down stairs. I felt no fear, I didn't think we could be hit, since my mother showed no fear herself. I knew that people were hit though. At a nursery school I attended one child stopped appearing at school and I heard that she had been killed. I recall her name, Valerie, because I had sat next to her for a time. I kept her drawing book in which she had painted what she said was “A pea family”. I guess she had been told the flowers she drew were members of that botanical order.

During the raids my mother used to look into a coal fire which we could see from the door of the “air raid shelter”, and make up stories which were inspired by shapes she showed us in the fire. After the war, I boasted about her apparent courage when my first 'girl' came to tea. My mother interrupted: “I was in a state of blue funk from start to finish” she said. My father was not afraid though - he had been in the trenches and fought in the Battle of the Somme. He had got used to being shelled all day every day. “But as long as you don't have to do anything” he said, “its OK”. Neither he nor we thought anything of his Somme medal. “We all got them” he told us – no heroics then – we believed him.

Each morning after a raid we ran to school, hoping to see new bomb damage, and find shrapnel which boys collected. We backed onto the cricket field in the Crystal Palace Grounds (now a park, then being used by the army). One could trace the line of bomb craters, like a malevolent giant's footsteps stalking across the field culminating in a direct hit on a large nursing home (Parklands). This was largely destroyed leaving only a beautiful dome almost like the Hiroshima memorial. Like all the kids we played amongst the willow herb in the dangerous ruins. We and our friends 'owned' bomb-craters which remained for years after the end of the war. The water filled ones were very educational - with dragonflies, water-boatmen, water-spiders and so on. One night an incendiary bomb fell in our tiny front garden, and my mother couldn't open the sack of sand you were supposed to empty on them. She says she tipped the cat's earth box on it - but I have no recollection of that. Another time the soldiers in the requisitioned house next door, who we children had befriended, pulled us into their practice trenches when a siren suddenly sounded in the day. I looked up and saw a plane screaming across the sky with tiny sparks on the leading edge of its wings. For us it was a Spitfire shooting down a Messerschmitt, but of course it might have been the other way round.

When the V1's began to arrive it was very terrifying, as they sometimes came with no siren. When their engine cut out, the residents below had a few uneasy seconds to wonder where they were going to land. It was said you could hear them coming through the air, if they had your house number on them. We were fortunate to survive a narrow escape, but it pushed my poor mother into a nervous breakdown. She had set out with us from Crystal Palace, to visit Horniman’s museum which was situated in nearby Forest Hill. As we came out of the house, I looked up and saw what appeared to me to be an odd-looking aircraft. I was familiar with the shapes of the more common planes that flew around, but this seemed quite unlike them, having very stubby wings. Whether this was the V1 that occurs later in the story I don't know. If it was, it must have circled around for at least fifteen minutes before it fulfilled its purpose. We took a bus near to the museum - and stopped off at a sweet shop. There my mother got into an argument with the shop assistant who was talking with another person instead of attending to her. We were all obliged to walk out as an ostentatious demonstration of my mother’s anger. We children were not pleased as we walked along toward the museum. A few minutes later there was the loudest bang I had ever heard, and some of us fell down. As we got up we saw that a bus had stopped at a rather acute angle to the kerb - I don't know if it was pushed there by the residual blast or if the driver reacted in surprise. He looked at us and asked us if we were hurt. My mother was very shocked, and he offered us a free ride back to our street which we accepted. As we went past the row of shops my mother shouted that the sweet shop, from which we had walked in a huff, had been 'bombed out'. I looked and saw a lot of bricks and glass lying at the side of the road and people running out of surrounding buildings. Later on she used to swear that the shop had been completely demolished, but I don't recall seeing any actual gap in the stand of shops.

Shortly after that my mother told my father that she couldn't take any more and we left for Oxford to stay with relations. My mother just wrote them a letter and set out once she thought they had got it. On the way we saw the build up of war materiel at the side of the track. I watched a Bristol Beaufighter land amid huge clouds of smoke. My mother asked my father if it had crashed, but I think it was just dust on a hot summers day. All the aeroplanes and gliders had black and white stripes on their wings - all boys knew them to be 'invasion planes'. On the train a kind older couple agreed to take my two older sisters for the night. They later reported that they were terrified and thought the kindly woman was trying to poison them when she offered sweets. On arrival at Oxford I got lost, and was taken in hand by a WAAF who sat with me where she found me, until my father reappeared. As we approached the house of my aunt we saw her sitting in an upstairs window. I couldn’t follow the conversation between her and my mother, but in later years I heard that it went something like this. Mother – desperately: “Did you get my letter? Aunt - frigidly: “yes – but didn’t you get my telegram?” We stayed in Oxford for 14 weeks with a nice old couple who couldn’t have been kinder, with five extra people to cope with – my father having returned to London. We took a trip down the river to Abingdon, our steamer staying close to another one full of young men in cobalt blue uniforms, some with manifest injuries. “Aren’t they quiet?” my mother said to two ladies we were befriended by. It turned out they were convalescent American aircrew. “They are on our side” my mother said. I have never forgotten their white uncertain faces. They had seen the horrific face of war.

The V1 menace passed as the invading forces overran the launch sites, and we returned. On the way up the hill from the station we heard – out of the blue – a sudden huge bang. It was the second loudest I ever heard, after the V1 in Forest Hill. We got home very shaken, to hear later that a new weapon had been launched at us – the first of the V2 rockets. Even aged six I could see how crestfallen my poor mother looked. And a week or so later her sister’s flat was badly damaged when one hit one end of Park Court, the stylish apartment block lower down the street in which she lived with her son. The boy, who was my age, told me he had looked at the wreckage and seen the V2’s nose “with German writing on it”. At the time I believed him but of course it was nonsense. His mother broke down and my elder sister later acted out the sudden collapse in tears which she had witnessed. “Uncle Jim hasn’t written since he was taken prisoner”, she told us. He had been captured at some point, which my mother rather callously told us “was not very glorious”. Other husbands, sons and fathers were not so lucky. I recall a discussion between my sympathetic mother and a friend who had lost a son, where the phrase “right through his helmet” in a rising tone of distress culminated in a hysterical outburst which I found frightening.

I was in bed when news of the surrender came. All the electric trains whose tracks infested the area stopped and turned on their strange whistles. The next morning the world was exactly the same, but completely different. It was a sunny day and looking at the urban flower beds near the shops I got a picture of blue sky, green grass and scarlet flowers, and it was peace. There were lots of celebrations, and we walked up to Crystal Palace and looked out over the city where bonfire after bonfire into the distance were blazing like ever receding sparks.

The park with its bomb-craters and its reel upon reel of barbed wire and other seemingly unused equipment was cleared by the German prisoners and we befriended them as we had the soldiers before them. One said to my mother “We give you tea, we demand coffee”, just like a real German was supposed to talk, but she understood it was a confusion in the simple English they were learning. The trade was established. They used to sit in a circle at their breaks and sing snatches of English songs they were learning “Spring is coming, spring is coming, all the little bees are humming”. One man picked up my little brother who had long blond hair and danced with him in his arms saying “I am going to take him back to Germany”. I ran in, in a panic, thinking he was going to finally show his true Nazi qualities, but my mother was watching from the gate and just took my hand. Peace had arrived, and with it my little brother’s epilepsy, and a polio outbreak which raged around the area. That vision of blue sky, red flowers and green grass has stayed with me all my life – I always dream of peace. But I know now it’s the one thing you never get – that dream cannot be realised.

Contributed originally by Peter R. Marchant (BBC WW2 People's War)

Don’t tell Adolf about the wonders of country living for a small city boy. Don’t tell Adolf about the exciting playgrounds of the bomb damaged houses. Don’t tell Adolf about the excitement of the search lights and the guns and don’t tell Adolf how he changed my early childhood into an adventure often frightening, but with vivid memories I recall to this day.

My very first ever memories are framed by the war. It must have been sometime in 1940 when I was almost four years old. Our family, my Mum and Dad and my older sister Thelma, were living in a Victorian row house in Clapham, London. This area has now become quite fashionable with house prices equal to my father’s life time income. Then, it was a working class neighborhood, clean and respectable, populated by postmen, mechanics and lorry driver tenants like my father. The only thing I can remember about the interior of the house was the Morrison shelter in the center of the bedroom. There I spent many weeks of isolation with a severe attack of the mumps in uncomprehending discomfort, picking at the grey paint of the cage unable to take anything more solid than my mother’s blancmange and barley water, her remedies for all known human ills. I’m sure my parents were grateful the authorities provided us with a combination bomb shelter, table and sick bed, although I wonder was anyone actually saved by this contraption? This was a time when one’s betters weren’t questioned; my family rarely doubted they must know what was best for us. For those who know only about more serious bomb protection the Morrison shelter consisted of a bed surrounded with stout wire mesh and a steel top on four corner legs about the right height for a table. The idea was to prevent the occupants from being crushed to death under falling masonry, a small sanctuary to wait in, listening for the scrape of shovels and praying to be rescued before the air ran out. In addition to the ugliness and awful paint its major flaw was the assumption that we would all be in bed when the house collapsed, a family so stunted by food rationing that we were able to sleep together comfortably in a double bed. Did Adolf realize the Morrison was part of the propaganda war designed to show the Germans that we English were just as viral as the master race; a people that only needed a tin bed as protection from their bombs?

As I got better I was allowed to play in the garden at the rear of the house. I remember it as long and narrow flanked on one side by the windows of a small factory making parachutes, or bully beef, or some other necessity for killing the enemy. The weather must have been hot as I recall the young women talking to me through open windows. They seemed happy in their factory routine and the pound or two a day they earned which was probably the best money they had ever made. Or were their smiles just for the rather shy little boy they gave the small pieces of chocolate and orange segments then as rare and sought after as black truffles? If there’s a page in the calendar that can marked as the beginning of my generally good relations with the opposite sex it’s probably spring 1940.

There are many more memories that come to me clearly but they are mixed in a jumble of time. It must have been after the serious bombing of London started in summer 1940 that my sister and I were evacuated. We were all caught up in a great sea of events and

if the choice for our parents was having us with them so we could all be reduced to rubble together or safe country life for their children, it was not difficult to decide which train to catch. An adult knows the terrors and uncertainty of the world and has worries beyond tomorrow but a small boy knows only the moment and thinks of an hour as an eternity if an ice cream is promised.

We were sent to live with a Mr. and Mrs. Daniels and their two sons on their small holding at Gidcott Cross, a junction of narrow country roads about six miles from the market town of Holsworthy in the county of Devon. The surrounding country was divided into small irregular fields on a plan lost in antiquity, surrounded by tall hedges topped with thick bushes and occasional trees.

Many evacuees have grim stories to tell and we were very lucky to be in the care of a loving couple who treated us like their own. The Daniels had a few acres near the house and some additional pasture rented nearby. On this they kept a few milk cows, all with pet names, Daisy, Sadie and Jessie, a pig or two and a muddy barnyard full of chickens. A pair of ducks stayed most of the year in a narrow rivulet that ran around the house. A female dog Sally, always ready for a rabbit hunt, followed us around everywhere when she was not ensuring a new supply of terriers. The farm house had, or rather has, as it seems little changed over the years, thick rough walls yearly whitewashed, four or five rooms in two stories under a thick thatched roof. The Daniel’s house was at the foot of gently sloping fields set back from the road with a pig barn on the left and the milking shed and hay storage on the right of the heavy slab stone front path.

Mr. Daniels was a member of the local Home Guard, a group of tough wiry men too old for immediate military service. There were no blunderbusses or pikes, but modern weapons were in short supply. Mr. Daniels had upgraded to a worn double barreled shot gun a deadly weapon in his hands as all the rabbits knew. At lane intersections old farm wagons loaded with rocks were ready to be pushed into a road block. One clever ruse was redirecting the road signs, a confused German being thought better than a lost one. Any one advancing down the road to Holsworthy would find them selves in Stibbs Cross with only one pub, a much less desirable place to take over. The home guard met regularly near our cottage for drill and comradeship. It was so popular that the institution lived on well after the war as a social club. These men knew every blade of grass for miles around and would have caused any German paratroopers much annoyance if Adolf the military genius had ordered landings in this remote corner of England.

When they were not repelling German invaders the Home Guard kept an eye on the Italians in the area. Up the road was the Big Farm, big because it had a barn large enough to house a half dozen trustee Italian prisoners of war working the land. Riding on farm wagons pulled by huge shire horses, as petrol was very scarce, they would stop outside our cottage on their way to the fields. They looked like old men to me though they were just young boys probably not yet 18, endlessly happy to be out of the war, captured by a humane enemy and ending up in this idyllic setting. They carved wooden whirligig toys with their pen knives for me and the nostalgic Italian songs they sang I can hear in my mind to this day.

It was a wonderland for we city kids with farm animals, the open country to explore and no shortages of food. The farm was in most ways self supporting, if you wanted a stew you shot a rabbit or two, or cut the throat of a chicken. I helped with the endless farm chores collecting eggs every day from the nest boxes, when the chickens were good enough to cooperate. Many chickens didn’t appreciate the conveniences we provided and made the job into an adventure searching the hedgerows for errant layers. No tinned or horrible dried food for us, everything was fresh as the vegetables pulled from the ground within sight of the front door. When we eventually returned to London my sister and I were noticeably well fed and quite fat, the battle for my waist line probably goes back that far!

Without modern conveniences it took most of the daylight hours to keep the house running and everybody was expected to pitch in. Another of my ‘helping’ jobs was to help fill the water barrel. With a small boy’s bucket and many trips I walked up the road a hundred feet, to the well hidden in a hedge tangled with wild roses, pushed the wooden cover aside and, after tapping on the surface to send the water spiders skimming out of the way, dipped in my bucket. This taught country ways very quickly and water became a precious commodity to be recycled for many uses until it was finally used to scrub down the flag stone floor. The water was heated in a large black iron kettle hung on a chain over a log fire in the inglenook fireplace the only source of heat in the house. Cooking had changed little over hundreds of years and savory stews and soups were made over the burning logs in large iron cauldrons. There was no electricity or gas in our cottage and finer cooking required Mrs. Daniels skillful fussing with a flimsy paraffin oven in the back room from where emerged a stream of delicious pasties, or covered pies, filled with a range of edibles that would have surprised even a Chinese cook. These pasties were brought out every meal covering the table with a smorgasbord of dishes from ham and egg, potato and wild berries, until finished. The men took them into the fields stuffed in their Home Guard haversacks and with a jug of local cider and after grueling days in the sun bringing in the harvest ate dinner sprawled against the hay stacks. The days ran with the cycle of the sun; the evenings were lit sporadically with a noisy pressured paraffin lantern and bedtimes were shadowy with the light of candles.

I remember my evacuation with the Daniels as an idyllic time although now I detect there must have been a feeling of abandonment and bewilderment long buried. One of my parent’s visits I didn’t recognize the lady with my father as my mother had just started wearing glasses. Later on, another visit, I wandered the lanes all day looking for them on a country walk they had taken and was tearfully relieved to find them sitting in a field eating sandwiches having no idea how upset I was at being left. Evacuation must have had a profound effect on many young children like me. My wife thinks that this experience is the cause of many of my strange ways and quirks of personality although I claim genius has its own rules.

My sister and I were returned to London after a couple of years in the country, the precise timing is vague in my memory. The aircraft bombing was much less now although the sirens still wailed for the occasional raid setting the guns booming on our local Clapham Common. I wish I still had my treasured collection of shrapnel from the antiaircraft shell bursts that rained down razor sharp fragments of torn steel and made being outside as dangerous as the bombing. These would be poignant reminders of this time so distant it feels like another life. Memories of my best friend Basil who always managed to find the pieces with serial numbers, the most coveted in our collection.

I recall one night the warning sirens sounded and the sky was lit by searchlight beams probing for the attackers. Within minutes the street was as bright as the sky, plastered with small oil filled fire bombs. They were everywhere causing small fires in the gardens and on the roofs of our street. One slid through the slates and wedged itself under the cooker of our upstairs neighbour, Mrs. Tapsfield. My father spent the night running up and down the stairs carrying buckets of dirt from the garden and spraying the cooked cooker with a stirrup pump. I can, even now 60 years later, see my mother next morning standing on a chair with a hat pin puncturing the hanging bladders of water filled ceiling paper from the flood upstairs. The fire bombs caused a lot of minor damage but they were all damped down and none of our neighbours lost more than a room or two. For many years after the sheet metal bomb fins would turn up when a new flower bed was dug deep. The trusty stirrup pump gathered dust in the coal cellar ready in case it was of need in another war in the new atomic age.

England was a very grey place with some rationing into the 50’s. For us kids Clapham was a wonderland of bomb damaged play houses and vacant rubble strewn lots. There were complete sides of buildings missing leaving the floors with wallpapered rooms precariously suspended. Bath tubs and staircases were stuck teetering to a wall with no apparent support stories up and the cellars were half filled with debris with only dusty tunnels for access. You can imagine the games these inspired for us boys. A special game was attacking and defending the half flooded abandoned concrete gun emplacements on Clapham Common and exploring the communal air raid shelters dug in the square. If only our parents had known!

How do you remember the events of a war time childhood? Memories are like a damaged film, occasional clear scenes separated by long stretches scratched and out of focus.

Through the often repeated stories distorted by their retelling; by today’s chance incidents that start a flow of thoughts to a half forgotten scene. Was it a page in a book or an E mail from a friend, who can tell the truth from imagination? I cannot be sure of the exact timing and the precise details of my experiences in WW2 they have been rounded off by time, and in this diary I have done my best. Although the accuracy may not be perfect and who can be sure in the valley of the shadow of memory, I hope to have conveyed the atmosphere of my experiences in these anecdotes.

Contributed originally by jogamble (BBC WW2 People's War)

My Grandfather was Flight Lieutenant Leonard Thomas Mersh and this is just a glimpse in his life during World War 2, like many of the pilots he has a number of log books, with many miles accounted for and the stories to go with them.

Len went to Woods Road School in Peckham and then on to Brixton School of Building, where he qualified as a joiner. In 1938 at 18 he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. At Aberystwyth he made the grade to be a pilot and was then sent to Canada for further training in Montreal and Nova Scotia Newfoundland where he gained his wings on Havards and Ansons.

Once back in England he went to Aston Downs and flew many aircraft across England, eventually he was posted to East Kirby in Norfolk attached to 57 Squadron Bomber Command. He flew many missions over Germany and France and as far as the Baltic. Missions included laying mines in the fjords where submarines and battleships where hidden. Dresden; Droitwich, Hamberg, Nuremberg, Brunswick and Gravenhorst were some of the places he bombed. Some times he carried the Grand Slam bomb.

In January 1945 he and his crew where sent to Stettin Harbour to lay mines at night. They where one of the lucky ones, as 350 planes had been sent and only 50 came back. Granddad’s plane was attacked by enemy fighters and was hit but they managed a second run over the target to release their mines.

In March 1945 during a sortie against Bohlen, his aircraft was attacked by a Junkers 88. The plane was hit but they made three bombing runs and then hedgehopped back to England.

On the 26th October 1945 Leonard was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, (DFS), for courage, determination and efficiency.

After completing operational tours and six mine laying sorties he was drafted to 31 Squadron, Transport Command at the end of the Dutch Indonesian Campaign flying VIPs. He flew General Mansergh to Bali being the first RAF plane to land on March 8th 1945 to accept the Japanese surrender.

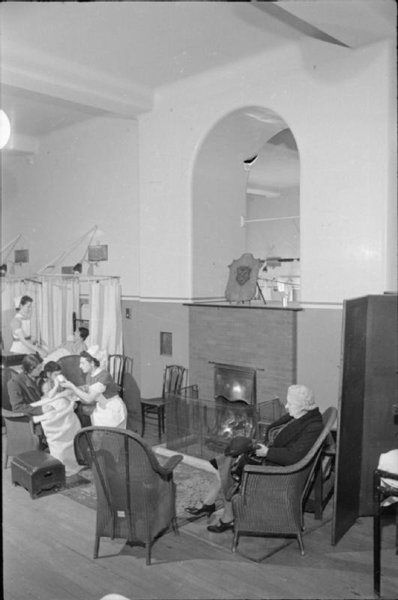

In 1948 Leonard was drafted to Germany to help with the Berlin Airlift. The squadron reopened airstrips which had been closed at the end of the war, plot routes into Berlin and get them working, the Americans would move in and the squadron would move on to another station. They flew by day and night and were lucky to gain 5hours sleep, which was taken in Mess chairs, which is perhaps why he caught TB, which ended his career and he then spent a lot of time in and out of hospital.

Contributed originally by Jean_Jeffries (BBC WW2 People's War)

First thing I remember of September 1939 is being told we must deny any Jewish family connections.

We lived in a fairly large house opposite Clapham Junction, South London. We quickly moved house to one further from the busiest railway junction in London, which was a prime target.

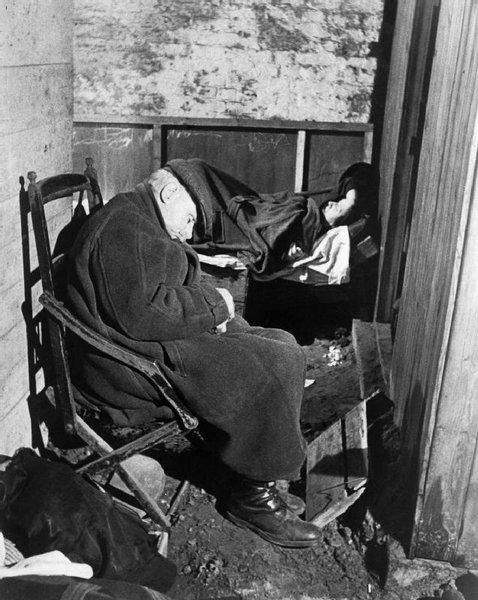

Our first Air Raid Shelter was the London Transport underground tube station. Bunks had been placed along the platforms and each evening, we would arrive with a few possessions and take our place in a two-tier bunk; the only privacy was a blanket suspended from the top bunk. At this time, my father was a fire-fighter so mum was alone in the Tube with two small children. If one wanted the loo, we all had to go, complete with any possessions - teddy bears and dolls! I was very nervous, not of bombs but of some of the weird people who we were living so close to.

If we were out during the day and a siren sounded, some of the shops would open the trap-door in front of their shop (which was used for deliveries) and we'd scuttle down the ladder. My favourite shop was David Greigs, us kids were spoilt there. I always dawdled outside hoping the siren would sound, never giving a thought to bombs! Then the Government installed the Anderson Shelter for each family. It was sunk into the ground for about 3ft and measured roughly 9ft by 9ft. It had two, two-tier bunks and accommodated our 6 family members with a squeeze. This was luxury after the Tube, but, being below ground level with no ventilation, it was damp and began to smell. Everything went mouldy and I still recognise the smell. I hated the toilet arrangements - a bucket outside for use during a lull, brought inside for use during a raid. During this time, my brother, aged 5, developed asthma and my father T.B., although he was not aware he had it. Dad got his calling-up papers and was turned down on medical grounds, but the examining doctor refused to tell him why or warn him of the Tuberculosis they'd found. I heard my parents worriedly discussing it and I was glad he wouldn't be going to war.

The evacuation of London began. I was ready to go with my gas mask, case and with a label tied to my coat. My brother was too ill to go, so, at the last minute, my mother decided to go also and take him away from London. So we set off for some vague address in Bakewell, Derbyshire. Families in safe areas were ordered to take in evacuees and, in this house, we were resented and made to feel very unwanted. Food, already scarce, was even more so for us. Our mean hostess fed her own family well with the rations intended for us. Within a month we had left and it was years before I ate a Bakewell tart or admitted Derbyshire was beautiful!

Next, we reached an old farm cottage in Bampton, Oxfordshire. Our landlady was a Mrs Tanner, a warm-hearted person who made us welcome with a full meal and a blazing fire - what a difference!

Mrs Tanner was the wife of the local Thatcher. They kept livestock for their own food, as country people did then. Despite being Cockneys, we had come from an immaculate home with electricity, hot water, a bathroom and an indoor toilet. We now found ourselves in this warm, well-fed friendly cottage with friendly bed bugs, kids with head lice, a tin bath hanging on the garden wall and a bucket'n'plank loo in the yard. The loo had a lovely picture of "Bubbles", the Pears advert, hanging on its wall - very tasteful.

On Thursdays, all doors and windows were tightly closed whilst we waited the coming of the Dung men; two gentlemen wearing leather aprons emptied everyone's buckets into their cart. What a job!

My brother was very much worse, skinny and weak with breathing difficulties. He spent time in hospital and mum stayed with him. Mrs Tanner treated me like yet another grandchild and I soon settled happily into my new way of life. Mum asked her if she would take me to the town, a bus ride away, to get new shoes and some clothes. Off we went on what was literally a shop-lifting spree. I was both frightened and excited and sworn to secrecy. Mrs T. kept the money and the coupons and mum was thrilled to have got so many bargains. I never told her! But, when I wore my new shoes or my finery, I always dreaded someone asking me questions. I laid awake at night rehearsing my answers. I was never tempted to try it myself. When I see Travellers, kids, I often think "that was me once". After a year of my idea of heaven, mum decided to return to London to see if the hospitals there could help little Eddie. We got back just in time for The Battle of Britain; I'm glad they waited for us. I was so homesick for Bampton that I even contemplated running away to try to go back. Although I settled down, I still think of Bampton as my home and, after 63 years, I still go back for holidays. Just one year made such an impression on me. It was so carefree and I enjoyed some of the jobs with the animals.

During the time we were away, my dad had carried on with his job and Fire-fighting in London. Our home had gone, so we stayed with an Aunt until we got somewhere to live. Empty houses were requisitioned by the Authorities, who then allocated them to those who needed them. My parents applied for a house, explaining that Eddie needed to be near a hospital, but they were told that, as the father was not in the forces, they did not qualify for accommodation. They were heartbroken as a doctor had informed them that, without a decent home, Eddie would not live long. My father insisted on volunteering for any of the forces, but was once again declared unfit. Eventually, after mum worried them every day, we were given two rooms in a small terraced house, sharing a toilet with another family. There was no bathroom and we were made to feel almost like traitors with frequent remarks directed at my dad. Even at school the teachers singled us out with "anyone who's father is not in the forces will not be getting this" - this could be milk or some other treat we regarded as a luxury. One teacher was so obsessed that today she would be considered mentally unbalanced. A project she gave us 10year olds was to devise tortures for Hitler or any German unlucky enough to survive a plane crash. I cheated and copied one from a book.

Our shelter was now a reinforced cellar. It was dry and spacious and, during heavy bombing, some of our neighbours joined us and we had what I considered to be jolly times together. Food was in very short supply; although we had ration books, there was not always enough food in the shops. I was sent to queue up, then mum would take over while I queued again at the next shop with food, where we repeated the pattern. I once reached the counter before mum got there; we were waiting for eggs. I got 4 eggs in a paper bag and, as I left the shop, I dropped them. Carefully carrying them back to the counter I told the assistant she had given me cracked eggs. I was shouted at and called a lying, nasty little girl but managed to obtain 4 replacement eggs. I just could not have told my mum I'd broken them.

A neighbour of ours was a fishmonger, poulterer and game merchant. He sometimes had rabbits for sale; they were always skinned and usually in pieces. After bombing raids, there were often cats straying where their home was destroyed, or dogs wandering about the streets. We think our fishmonger solved this problem. I believe most women realised the meat wasn't quite what they wanted but had to have some meat to put in the stew. Luckily we had a vicious wild cat I had taken in and being so spiteful, she lived a long and happy life, occasionally bringing home a piece of fish. How she managed this I don't know. Could it have been bait for a lesser cat?

School was rather a shambles. We had our classes in a shelter, that is 2 or 3 classes at a time; as there was insufficient room for all the children we had mornings or afternoons only. The other class we shared our shelter with always had such interesting lessons! I feel awful about admitting this but the education system was so easy to play truant from. If you didn't turn up they assumed you'd been bombed or sent away to safety. A couple of friends and I used to ignore the danger of air raids and go to the centre of London where we could be sure of meeting American servicemen. We begged for gum or chocolate from them, then had to eat or hide it before going home. At no time did we ever think of how our families would have no idea where we were if we never came back. It's rather frightening really. Our excursions came to an end when, on a very wet day, mum came to meet me from school with an umbrella. After waiting until all the kids had left, she went in to see our teacher who said I had not attended for some time and thought I had gone back to Bampton. Boy, did I get a beating! She was as vicious as my cat but not as lovable.

One night we were in our shelter when a neighbour called us to come out to see the incredible amount of German planes that our boys were shooting down. We stood outside in the street and cheered, linking arms and dancing. The next day we heard on the radio that they had not been shot down but were a new weapon - the Doodle Bug. From then on I understood fear. I don't know what triggered it but I joined the ranks of the old dears who swore they recognised one of ours or one of theirs. I henceforth scrambled to get my pets into the shelter as soon as we heard the siren. My dog soon learnt this and was first down; her hearing being keener than ours, she could hear the siren in the next town before ours. Soon we had Rockets. There was no warning with them. The first one we saw was on a summer's evening when my friends and self were practising the Tango on the street corner. We were singing "Pedro the Fisherman" as a whine came from above our heads, followed by a cloud of dust and then the impact and sound of the explosion. Four screaming dancers rushed for shelter. We knew many of the people who had been killed or injured and it seemed too close to us. It never had been safe but we hadn't noticed it before, now I did, worrying, "where did that one land?" "Is it near dad's shop or near our relations?" I guess I'd grown up but it was so quick. I was twelve, learning to tango and worrying about our family. I decided I would join the Land Army as soon as they would let me; I'd heard one no longer needed parents' permission. This was not anything to do with the war effort. I simply wanted my life back in beloved Bampton. My feelings were mixed when the war ended, no more terrifying Rockets but trapped in London with no chance of getting away until I married!

Contributed originally by CSV Solent (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People’s War website by Marie on behalf of John and has been added to the site with his permission. John fully understand the site’s terms and conditions.

In 1943 a call went out for young men to train as railway shunters on the mainland. I volunteered and within a few weeks I was sent to the marshalling yard at Feltham in Middlesex. The size of the place was an eye-opener — it had 32 miles of track and sidings and a fleet of nearly 100 steam locomotives. I was given lodgings with the family of one of the yard foreman, gave my ration book to his wife and then had 2 days to look round and familiarise myself with the yard and the workings of this vast layout. After another couple of days to learn the rudiments of loose shunting, I was assigned to a shunting gang which consisted of two class three shunters and one class one shunter who was in charge. The class Three shunters were, depending on their knowledge, either working the hand points or unhooking the wagons to get them marshalled in station order. You had to do a lot of running to keep up with the work and I was put on the shunting pole unhooking the wagons and working twelve hour shifts. When I started in this gang I was told how the previous shunter had had a very serious accident and had both his legs amputated below the knee which wasn’t the kind of thing I needed to hear. There were a lot of points that needed to be stepped over — on the night shift with restricted lighting this was difficult and made even worse by air raids when all the lights would go out but we had to carry on working until the German bombers went over when we would go for shelter, or when the nearby anti-aircraft guns started firing and shrapnel would rain down like confetti.

After working twelve hour shifts I would arrive at my lodgings very tired and filthy so would wash and clean up, have my meal and then go straight to my room and bed. One evening I was woken up by the husband banging on my door — the Germans had been dropping bombs on a nearby depot but some had started landing on the roofs of the local houses and everyone was outside with ladders and rakes getting these incendiary bombs down onto the ground so they could be covered up with sand and earth which would put the flames out. And until I was woken up, I hadn’t heard a thing!

As winter fell shunting became even worse — we now had to contend with the black-out, frost, snow and ice underfoot and above all the London smog which sometimes lasted days. We had to carry out the flat shunting using whistle codes so the driver knew to pull up, set back or stop. Even so, there were derailments and collisions everytime the smog came down, and the freight trains leaving the yard were hours late. As these had to be slotted into the mainline passenger train service — with 4 trains an hour into waterloo and 4 trains an hour out, the signalman controlling all this mayhem had quite a job.

Early in 1944 the freight traffic started to increase more than ever — this was for D-Day, but of course we didn’t know it at the time. Because of shunting staff shortage I only got one Sunday off in five, when I would attempt to visit my family on the IOW. I would get away late Saturday afternoon and be back on Monday. This worked well until Saturday 4th June 1944 when I arrived at Portsmouth harbour to find that the paddle steamer boat service to Ryde had been suspended — the only boat to the IOW was the Portsmouth to Fishbourne car ferry and there were no more of them until Sunday morning. I went back to Portsmouth Town station, found somewhere to get a sandwich and a cup of tea and then saw the Station Forman and told him I couldn’t get home. He fixed it up for me to sleep in the compartment of an electric train and for someone to give me a call in time for the first car ferry. As this ferry came out of the harbour I saw rows and rows of ships large and small stretching out as far as the eye could see. The weather was terrible and I felt so sorry for all the soldiers being tossed about in the flat bottomed landing craft by the very rough sea. When the ferry landed, I got the bus home to Gunville and explained to my mother what had happened, had a meal and then had to go back to work. I heard that the invasion of Europe had started and turned up at the yard to find they were looking for volunteers to go as shunters in Southampton Docks to help deal with invasion traffic. I volunteered straight away and on D-Day plus seven, I was on my way. I had to report to the Dock Superintendant’s Office traffic Section — a large building in the old docks facing Canute Road. I was given my lodgings address and told to wait for the Superintendant — he noticed straight away that I didn’t have a London accent and his face lit up when I told him I was from the IOW. He’d been brought up in Alverstone which was the last station I worked at before I went to London. By now he’d obviously formed his opinion of me and he said “I know you’re very young, but if I offered you a Head Shunters job do you think you could do it?” I said I would give it a jolly good try and he sent me to the New Docks as the track layout was a lot easier to learn than at the Old Docks.

The next morning I reported to the New Dock Inspector and was assigned to a Head Shunter so I could start learning the track layout for the whole of the New Dock area. It was no easy task, but after nearly two weeks learning on different shifts I said I was ready to take over with my own engine. This job turned out to be one of the greatest experiences of my career. I had to deal with trains of petrol in jerricans, these had to be shunted out from the sidings, taken across the roadway and pushed onto the dockside at berths 107 and 108 to be loaded onto pallets and hoisted on board the ships. Ammunition was loaded at 101 and 102 berths, and things like large tents, nissen huts, picks, shovels etc were moved from berth 103 to 106. We also had three ambulance trains fully manned and ready to go 24 hours a day. Two of these trains were American and one of British medical staff, and whenever a hospital ship was due to arrive at the Old Docks, the New Docks shunters would have to pull these trains out of the sheds and over the Town Quay, threading your way between pedestrians and motor traffic, and all the vehicles that were parked too close to the railway lines that would mean you had to stop, find the driver and get them to move it so you could carry on. Some days there were many of these trips!

By now I had settled into my lodgings — the front bedroom and a small sitting room of a Victorian house in Winchester Road — and I persuaded the landlady to take in another shunter so I had some company when off duty. Shunters were allowed extra cheese rations and this pleased her, but not us — nearly every day we had cheese in our sandwiches! So being on a 12 hour shift I sometimes went into the Dockers Canteen where the food was basic but filling, and when off duty I went to the Government run British Restaurant serving wartime meals. This restaurant was on a bomb site in the High Street, Above Bar. But everywhere you looked there were bomb damaged buildings, especially in the Old Docks and surrounding areas. We were now getting Allied troops back from France, the first lot I can remember were the American Rangers from Normandy. They had taken awful punishment and lost a lot of men trying to get a foothold on “Omaha” beach landing. After some very severe fighting they had managed to advance inland, and now after a few weeks they were relieved and came back to England. They were being sent to London for Rest and Relaxation. The first train to leave with these bomb-happy troops kept getting stopped by some of them pulling the emergency cord and it took many stops and starts just to get to the Millbrook exit onto the mainline. The train driver and guard asked the Docks Traffic Inspector to get the officer in charge to stop the cord pulling or the train would not go any further as it would be a hazard to other trains on the mainline. Sure enough, that put a stop to all thr trouble!

Just outside No 8 gate, on spare ground sloping down towards the sea, the Americans had built a concrete hard to load tanks and troops. These large boats were departing one after another, and then after a few weeks the flow of men and tanks got less. They then laid temporary railway tracks down the hard and started loading railway freight vehicles. These had arrived as a kit of parts in large crates and were tested and assembled on spare land at the Millbrook end of the docks and then pulled down to Number 8 gate and pushed onboard. The track had to be flexible in places to compensate for high and low tide and some derailments did occur but a crane was kept on stand-by to deal with these. The boats started coming back full of German P.O.Ws instead of being empty. They were unloaded and marched to a very large compound of huts, and barbed wire which had been used by the Allied Troops days before D-Day. There they were deloused and then loaded back onto trains to be taken to Kempton Park Race Course or Newbury Race Course under a military escort to await dispersal to proper P.O.W. camps.

Amongst all of this work, we also had traders inside the docks who needed their wagons to come and go. Hibberts had wagons full of lager from Alloa in Scotland — it was bottled and ready to go onto ships; Cadburys had ships chocolate and cocoa arriving daily; there was Ranks Flour Mill supplies and Myers Timber Merchants receiving materials, plus coal for the coal fired ships, so we were kept very busy.

I remember receiving a letter from my mother early in 1945 with some bad news, our village had lost another young man, John Caute, who’d been a school friend of mine. He was serving in the “Royal Tank Corps” and had been killed crossing the Rhine River. There’s a plaque to his memory in the village church at Godshill where he was an altar boy.

V.E. Day arrived and I remember all the ships in the port of Southampton sounding the morse code V on their sirens and the church bells rang for hours, no black out restrictions anymore and the pubs were full that evening. The “Channel island” boat service started up taking refugees and supplies back with them. The Queen Mary came back into Southampton and the Queen Elizabeth came to Southampton for the first time since she was built. They were both still in wartime grey paint and put into service repatriating American troops — if memory serves correctly they took 10,000 troops at a time. Later the Queen Mary had to go into dry dock to have all the barnacles and weed removed from her her bottom as it was affecting her speed and steerage — I was one of the shunters who took away the loaded wagons of evil smelling scarpings. I made friends with the dry dock forman and he took me down the stairway to the bottom of the dock so I could see just how big she was, and the size of her proppellors and rudders. It was quite an experience! Then in 1946 I finished my time at Southampton Docks and was sent back to Feltham Marshalling Yard to become a train despatcher.

Contributed originally by 2nd Air Division Memorial Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jenny Christian of the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library in conjunction with BBC Radio Norfolk on behalf of Frank L Scott and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Part one

I was eighteen, going on nineteen, when the storm clouds of war started to gather. Life was good ; a happy home, loving and devoted parents and family, sound job prospects and a variety of interesting hobbies and out-door pursuits. All this adding up to an enjoyable and hopefully peaceful future. Life was indeed worth living!

My dreams were shattered on that morning in early September 1939 when the sirens sounded throughout the land warning 'Englanders' of an immediate air attack when the suspected might of the German Luftwaffe would rain down upon us.

Most people that could, and were able, ran for cover long before the mournful wail of the penetrating sound of the air-raid sirens had faded away.

My family consisting of Mother and Father, two sisters, three younger brothers and an elderly Grandfather took to our heels and made for the conveniently placed 'Anderson' shelter dug into the back garden. I can't remember the exact measurements of that particular type, but I do know that to house nine adults for any length of time, as it eventually did for several months to come, has to be experienced to be believed. Not only was it very uncomfortable in such a confined space but there was always a fear of the unknown horrors of bombing raids.

Within the shelter, there was the cheerful chatter to keep up our spirits but outside there was an uncanny silence which was broken some time later by the ALL CLEAR signal. A sound we got to love and hear. Nothing happened that particular day and we remained unscathed.

The sound of that very first warning at about 11 o'clock on Sunday 3rd September 1939 will long remain in the memories of many folk, the elderly and not so young, and was a discord we all learnt to live with and to rejoice endlessly to the welcome sound of the ALL CLEAR.

This situation continued for many months with warnings of imminent raids which came to nothing. So began the 'phoney war' as it became to be known. Because of the continuous interruptions caused daily when enemy aircraft were unable to penetrate the air defences, spotters were placed on rooftops of factories, offices, power stations etc., to warn workers only when there were signs of impending danger.

Unfortunately, this was rather short lived and many large towns and cities suffered badly when the German High Command decided to step up and concentrate on a more devastating and annihilating blow, in particular to the civilian population.

My personal experience of this period of time was when taking a girlfriend to a cinema in Elephant and Castle area of London and to be informed by the Manager of the cinema that a heavy bombing raid was taking place in the dock area of the East End. Not that that had much significance to a couple in the back row, who continued there until the bombing got worse and the Manager informed those remaining that the cinema was about to close.

Most people that were able to went underground that evening and it wasn't until the ALL CLEAR sounded in the early morning at daylight that they came out again and went about their business.

Living not far from this area, my first thoughts were for my family and I wished to check on their welfare as soon as possible. Because of the ferocity of the raid, there was much local damage and fires were raging everywhere, accounting for endless lengths of firemans' hosepipes to be trampled over in search of public transport which, by that time, was non-existent. Having escorted my girlfriend home which, unfortunately, was in the opposite direction to the one I would have wished to get me home quickly, but eventually I made it and found them safe and sound. A block of flats nearby had taken a direct hit during the raid.

This signalled the beginning of endless night after night bombing raids on London and 'Wailing Willie' would sound without fail at dusk about the time that mother would be putting the finishing touches to the picnic basket that the family trundled to the garden air-raid shelter. Not too often, but some nights for a change of scenery, or further company, we would go to a communal shelter but must admit that we all felt most secure at 'ours'.

So, life went on, come what may, raids or no raids. All went of to work the next morning trusting and hoping that our work place would still be there. Battered or not, running repairs would be performed and it would be 'business as usual'.

My father, being in the newspaper distribution trade and a night worker would clamber out of the shelter in the early hours but would return occasionally during the night to see that all was well. He would also drop in the morning papers which were often read beneath the glow of the searchlight beams raking the darkened sky in search of enemy aircraft. An additional item on one particular raid was when a nearby gasometer near the Oval cricket ground was hit and a whole cascade of aluminium flakes came drifting down in the light of the search light beams.

Being in 'Civvy Street' at that time, and in what was considered a reserved occupation with a company of manufacturing chemists, my only contact with the war and ongoing battles in various theatres of war was through the press. It was not until that little brown envelope appropriately marked O.H.M.S. fell through the letter-box did my involvement with the military begin.

"You will report" it began, and so I did to the local Labour exchange when it set the ball rolling with regard to medicals, which arm of the service, date of call up etc. I also remember that my company deducted my pay that day. Something I never forgave them for and therefore had no wish to rejoin them on release from the forces.

Came the day, or rather it very nearly didn't! One of the most frightening and devastating attacks on London came that night. The railway station that I had to report to for transport to camp had been put out of action and I can remember clearly seeing passenger carriages hanging onto the roads from railway bridges. Plan 'B' was immediately put into operation and road transport was made available to take us "rookies" to the next station down the line.

The Military Training Camp on the borders of Salisbury Plain became home for the next six weeks when one went through all the motions of becoming a fighting soldier, with discipline and turn-out being the Order of the Day. Whatever one says about Training Sergeants I think our Squad must have struck lucky because we decided to have a whip round and buy him a parting gift before our leaving camp and being drafted to a searchlight mob. Thus ended basic training in the Royal Artillery.

The next venue was over the border; a searchlight training camp on the West coast of Scotland. Within a very short time and very little action, boredom set in and a Regimental office notice calling for volunteers for Airborne Divisions prompted a few of my mates and I to put our names forward. Knowing the outcome of some of their eventual encounters in later battles I am thankful now that an earlier posting took me to a newly formed Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment of which I am justly proud.

Whilst serving with a searchlight Battery Headquarters in Suffolk, apart from the usual flak and hostile fire being an every day occurrence, Cupid's dart took a hand when the A.T.S. became part of the Establishment and a cute little red-head arrived on site. A war-time romance followed but a further posting from that unit took me to another part of the country. As the saying goes "Love will find a way" and it did for we kept in touch until distance and timing took its toll. That was over 50 years ago and through a twist of fate, a news item that appeared in a national newspaper put us in touch again.

My Regiment, the 165 H.A.A. Regt. R.A. with the fully mobile 3.7in gun had many different locations during the build up to D Day but it was fortunate enough to complete its full mobilisation for overseas service in a pleasant area on the outskirts of London. This suited me fine as it was but a short train journey to my home and providing there was no call to duty I would take the opportunity of going A.W.O.L. and dropping in on my folks for a chat and a pint at the local. However, I always made a point of getting back in time for reveille and no one was the wiser. It was also decided about that time that every man in the Regiment should be able to drive a vehicle before proceeding overseas so that was another means of getting up town for a period of time.

Inevitably all good things come to an end and we received our "Marching Orders" to proceed in convoy to the London Docks. The weather at that time was worsening putting all the best laid plans 'on hold'. Although restrictions as regards personnel movements were pretty tight some local leave was allowed. It would have been possible for me to see my folks just once more before heading into the unknown but having said my farewells earlier felt I just couldn't go through that again.

Part Two

With the enormous numbers of vehicles and military equipment arriving in the marshalling area and a continuous downpour of rain it wasn't long before we were living in a sea of mud and getting a foretaste of things to come.

To idle away the hours whilst awaiting to hear the shout "WE GO", time was spent playing cards (for the last remaining bits of English currency), much idle gossip, and I would suspect thinking about those we were leaving behind. God knows when, or if, we would be seeing them again. By now this island we were about to leave, with its incessant Luftwaffe bombing raids and the arrival of the 'Flying Bomb', had by now become a 'front line' and it was good to be thinking that we were now going to do something about it !!

All preparations were made for the 'off'. Pay Parade and an issue of 200 French francs (invasion style), and then to 'Fall In' again for an issue of the 24hr ration pack (army style), vomit bags and a Mae West (American style). Just time to write a quick farewell letter home before boarding a troopship.

Very soon it was 'anchors away' and I think I must have dozed off about that point for I awoke to find we were hugging the English coast and were about to change course off the Isle of Wight where we joined the great armada of ships of all shapes and sizes.

It wasn't too long before the coastline of the French coast became visible, although I did keep looking over my shoulder for the last glimpse of my homeland. The whole sea-scape by now being filled with an endless procession of vessels carrying their cargos of fighting men, the artillery, tanks, plus all the other essentials to feed the hungry war machine.

The exact role of my particular arm of the Royal Artillery was for the Ack-Ack protection of air-fields and consisted of Headquarters and three Batteries, each Battery having two Troops of four 3.7in guns, totalling some 24 guns in all. This role was to change dramatically as we were soon to discover. In the Order of Battle we would not therefore be called into action until a foothold had been successfully gained and position firmly held in NORMANDY.

The first night at sea was spent laying just off the coast at Arromanches (Gold Beach) where some enemy air activity was experienced and a ship moored alongside unfortunately got a H.E. bomb in its hold. Orders came through to disembark and unloading continued until darkness fell. An exercise that had no doubt been overlooked and therefore not covered during previous years of intensive training was actually climbing down the side of a high-sided troopship in order to get aboard, in my case, and American LCT.

This accomplished safely, with every possible chance of falling between both vessels tossing in a heaving sea, there followed a warm "Welcome Aboard" from a young cheerful freshfaced, gum chewing, cigar smoking Yank. I believe I sensed the smell of coffee and do'nuts!!

Making sure that the assigned vehicle for my entry into Normandy and beyond was loaded aboard I settled down, anticipating WHAT, but surveying the panoramic view as we approached the sandy shore by now littered with the remains of the earlier major onslaught.

Undoubtedly one couldn't have been too aware of the incoming and outgoing tides as the water was far too deep at the beach-head and found it necessary to cruise around until late into the evening before it was decided to make for the shore come what may!! By then it was time to join the other members of the regiment's advance party in the Humber staff car which included driver, a radio operator, the C.O. and Adjutant.

Following the dropping of the anchor, the loading ramp was immediately lowered to the accompaniment of the sound of the engines breaking into life. I think at that point the two officers became aware that we were still in 'deep water' for they decided to climb onto to roof of the 'Z' vehicle as it proceeded down the ramp. In spite of seeing the sea water gradually climbing half way up the windscreen the O.Rs feet remained reasonably dry and we made the shore with the aid of the four-wheel drive.

At the first peaceful opportunity it was essential to shed the vehicle of its waterproofing materials and extend the exhaust pipe. The canvas parts of this exercise I decided to keep, as I thought that they would be useful (time permitting) for lining ones fox-hole, which I later found to be ideal.

My ancient tatty looking 1944 diary informs me that I slept in a field and awoke at 05.30hrs to a glorious sunny day, that I washed in a stream,sampled my 24hr ration pack, saw my first dead jerry and that General De Gaulle passed the Assembly Point.

I must admit that without the aid of my diary that I managed to keep throughout the war (something that I could have been very severely reprimanded for had it been known at the time) and the treasured letters that my Mother retained until her dying day, I could not possibly remember all the most intimate details of my soldiering days.

Returning to those early entries, whilst enjoying the pleasure of a quick splash in a neighbouring stream I became aware of some girlish giggling in the adjoining bushes and felt that this was an early indication that the natives were friendly.

We proceeded inland, the Sappers having done their stuff and prepared safe lanes amid endless rows of tape with the deathly skull and crossbones indicating ACHTUNG MINEN, it was decided to set up Regimental H.Q. in the area of Beny-sur-mer.

During a check halt en route I noticed that a small area of corn a few yards into a vast cornfield had been disturbed. Taking a chance and feeling inquisitive I decided to investigate. And there it was the ENEMY, but proved not to be too much of a problem. How long he had been there I do not know. He was lying on his back, his feet heavily bandaged no doubt through endless marching, his Jack Boots placed beside his body. I also notice hurriedly that his ring finger was missing? Someone's Son, someone's Father, someone's brother, someone's liebe; what a ghastly business war is !!