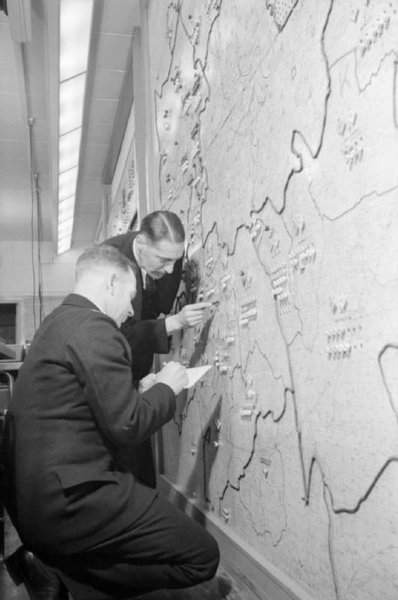

Bombs dropped in the ward of: Cathedrals

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Cathedrals:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 160

- Parachute Mine

- 1

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Cathedrals

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Home again in Bermondsey after the few months sojourn in Worthing, I saw my new baby sister Sheila for the first time. She'd been born on December 5, and Mum was by then just about allowed to get up.

In those days, Mothers were confined to bed for a couple of weeks after having a baby, and the Midwife would come in every day. In our case, the Midwife was an old friend of my mother.

Her name was Nurse Barnes. She lived locally, and was a familiar figure on her rounds, riding a bicycle with a case on the carrier. She wore a brown uniform with a little round hat, and had attended Mum at all of our births, so Mum must have been one of her best customers.

That Christmas passed happily for us. There were no shortages of anything and no rationing yet.

When we found that our school was re-opening after the holidays, Mum and Dad let us stay at home for good after a bit of persuasion.

I was a bit sad at not seeing Auntie Mabel again, but there's no place like home, and it was getting to be quite an exciting time in London, what with ARP Posts and one-man shelters for the Policemen appearing in the streets. These were cone shaped metal cylinders with a door and had a ring on the top so they could easily be put in position with a crane. They were later replaced with the familiar blue Police-Boxes that are still seen in some places today.

The ends of Railway Arches were bricked over so they could be used as Air-raid Shelters, and large brick Air-raid Shelters with concrete roofs were erected in side streets.

When the bombing started, people with no shelter of their own at home would sleep in these Public Air-raid Shelters every night. Bunks were fitted, and each family claimed their own space.

There was a complete blackout, with no street lamps at night Men painted white lines everywhere, round trees, lamp-posts, kerbstones, and everything that the unwary pedestrian was likely to bump into in the dark.

It got dark early in that first winter of the war, and I always took my torch and hurried if sent on an errand, it was a bit scary in the blackout. I don't know how drivers found their way about, every vehicle had masked headlamps that only showed a small amount of light through, even horses and carts had their oil-lamps masked.

ARP Wardens went about in their Tin-hats and dark blue battledress uniforms, checking for chinks in the Blackout Curtains. They had a lovely time trying out their whistles and wooden gas warning rattles when they held an exercise, which was really deadly serious of course.

The wartime spirit of the Londoner was starting to manifest itself, and people became more friendly and helpful.It was quite an exciting time for us children, we seemed to have more things to do.

With the advent of radio and Stars like Gracie Fields, and Flanagan and Allen singing them, popular songs became all the rage.

Our Headmaster Mr White, assembled the whole school in the Hall on Friday afternoons for a singsong.

He had a screen erected on the stage, and the words were displayed on it from slides.

Miss Gow, my Class-Mistress, played the piano, while we sang such songs as "Run Rabbit Run!" "Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree," "We're going to hang out the washing on the Siegfried Line," and many others.

Of course, we had our own words to some of the songs, and that added to the fun. "The spreading Chestnut Tree" was a song with many verses, and one did actions to the words.

Most of the boys hid their faces as "All her kisses were so sweet" was sung. I used to keep my options open, depending on which girl was sitting near me. Some of the girls in my class were very kiss-able indeed.

One of the improvised verses of this song went as follows:

"Underneath the spreading Chestnut Tree,

Mr Chamberlain said to me

If you want to get your Tin-Hat free,

Join the blinking A.R.P!"

We moved to our new home, a Shop with living accomodation up near the main local shopping area in January 1940.

Up to then, my Dad ran his Egg and Dairy Produce Rounds quite successfully from home, but now, with food rationing in the offing, he needed Shop Premises as the customers would have to come to him.

His rounds had covered the district, from New Cross in one direction to the Bricklayers Arms in the Old Kent Road at Southwark in the other, and it was quite surprising that some of his old Customers from far and wide registered with him, and remained loyal throughout the war, coming all the way to the Shop every week for their Rations.

Dad's Shop was in Galleywall Road, which joined Southwark Park Road at the part which was the main shopping area, lined with Shops and Stalls in the road, and known as the "Blue," after a Pub called the "Blue Anchor" on the corner of Blue Anchor Lane.

It was closer to the River Thames and Surrey Docks than Catlin Street.

The School was only a few yards from the Shop, and behind it was a huge brick building without windows.

In big white-tiled letters on the wall was the name of the firm and the words: "Bermondsey Cold Store," but this was soon covered over with black paint.

This place was a Food-Store. Luckily it was never hit by german bombs all through the war, and only ever suffered minor damage from shrapnel and a dud AA shell.

Soon after we moved in to the Shop, an Anderson Shelter was installed in the back-garden, and this was to become very important to us.

As 1940 progressed, we heard about Dunkirk and all the little Ships that had gone across the Channel to help with the evacuation, among them many of the Pleasure Boats from the Thames, led by Paddle-Steamers such as the Golden Eagle and Royal Eagle, which I believe was sunk.

These Ships used to take hundreds of day-trippers from Tower Pier to Southend and the Kent seaside resorts daily in Peace-time. I had often seen them go by on Saturday mornings when we were at Cherry-Garden Pier, just downstream from Tower Bridge. My friends and I would sometimes play down there on the little sandy beach left on the foreshore when the tide went out.

With the good news of our troops successful return from Dunkirk came the bad news that more and more of our Merchant Ships were being sunk by U-Boats, and essential goods were getting in short supply. So we were issued with Ration-Books, and food rationing started.

This didn't affect our family so much, as there were then nine of us, and big families managed quite well. It must have been hard for people living on their own though. I felt especially sorry for some of the little old ladies who lived near us, two ounces of tea and four ounces of sugar don't go very far when you're on your own.

I'm not sure when it was, but everyone was given a National Identity Number and issued with an Identity Card which had to be produced on demand to a Policeman.

When the National Health Service started after the war, my I.D. Number became my National Health Number, it was on my medical card until a few years ago when everything was computerised, and I still remember it, as I expect most people of my generation can.

Somewhere about the middle of the year, I was sent to Southwark Park School to sit for the Junior County Scholarship.

I wasn't to get the result for quite a long while however, and I was getting used to life in London in Wartime, also getting used to living in the Shop, helping Dad, and learning how to serve Customers.

We could usually tell when there was going to be an Air-Raid warning, as there were Barrage Balloons sited all over London, and they would go up well before the sirens sounded, I suppose they got word when the enemy was approaching.

Silvery-grey in colour, the Balloons were a majestic sight in the sky with their trailing cables, and engendered a feeling of reassurance in us for the protection they gave from Dive-Bombers.

The nearest one to us was sited in the enclosed front gardens of some Almshouses in Asylum Road, just off Old Kent Road.

This Balloon-Site was operated by WAAF girls. They had a covered lorry with a winch on the back, and the Balloon was moored to it.

I went round there a couple of times to have a look through the railings, and was once lucky enough to see the Girls release the moorings, and the Balloon go up very quickly with a roar from the lorry engine, as the winch was unwound.

In Southwark Park, which lay between our Home and Surrey-Docks, there was a big circular field known as the Oval after it's famous name-sake, as cricket was played there in the summer.

It was now filled with Anti-Aircraft Guns which made a deafening sound when they were all firing, and the exploding shells rained shrapnel all around, making a tinkling sound as it hit the rooftops.

The stage was being set for the Battle of Britain and the Blitz on London, although us poor innocents didn't have much of a clue as to what we were in for.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

I arrived home at Bermondsey from Torquay in 1941 to find that things had changed dramatically.

The Shop-windows were still plate-glass, but all the window-frames of our House were covered in opaque plastic, which only let a little light in.

I was the last one to come home.

My eldest brother John, had left School and was now a GPO Telegram Boy, with blue uniform complete with red piping, Pillbox Hat and red Bicycle.

Percy took his place at the Borough Polytechnic, a Technical School in Southwark, so he was settled.

Iris and Beryl had also come home from Exeter, as they were unhappy there, and were back at the local Junior School, which was open again.

However, the biggest change was in the Shop, and to explain things properly, I must digress a bit.

At the top of Galleywall Road where it joined on to Southwark Park Road was the "John Bull Arch", named after the Pub alongside it.

It was (and still is), a wide brick-built Railway Arch with steel girder framework over the roadway on each side, carrying many of the lines into London-Bridge Station from Kent and the Suburbs.

There were paved foot-tunnels either side of the Roadway.These had been bricked-up at each end, and were used as Air-Raid Shelters.

They were fitted out with bunks, and many of the local people who didn't have a Shelter at home slept there every night.

The Arch suffered a direct hit on Sunday 8 December 1940, and over a hundred people were killed, including most members of a family who lived across the road from our shop.

One of them was a boy about my age, Charlie Harris, who went to my School before the war.

Recently, while doing some research on my Uncle, who was missing in WW1, I found that the War Graves Commission has a Civilian War-Dead Register, and there, sure enough, I found Charlie's Record of Commemoration. To read it made me feel very sad, but it's good to know that Civilian Casualties aren't forgotten altogether.

That Arch was a very unlucky place, apart from more near misses with casualties in the bombing, there were two direct hits on it by V2 Rockets in November 1944. The first one was on a Friday Morning. It demolished most of the Arch and devastated the area. Two Sundays later, when the wreckage had been cleared and a Temporary Bridge put up, another Rocket landed in exactly the same place, so the Workmen were back to square one, and we lost many more Friends and Neighbours in both incidents.

But back to 1941.

Along by the "John Bull" Pub, there was a large Greengrocer's Shop, which also sold a bit of Grocery. It was damaged in the bombing of the Arch, and the Couple who ran it had had enough by then, so they decided to close down and move out of London.

One had to be licensed by the Ministry of Food to sell Foodstuff during the War, and the local Food-Office asked Dad if he was interested in taking over the License, as his was the nearest Food Shop.

Dad was only too pleased to take it, as he was having a thin time of it with the Rationing.

He bought all the Scales and Equipment, so he was now also a Greengrocer, selling fresh Fruit and Vegetables, as well as some Grocery, Eggs and Butter.

This meant an early morning visit to Market for fresh produce every day.

Dad had a friend with a Greengrocery Business a little way away who had a Horse and Cart.

He would pick Dad up very early in the mornings, on his way to the Borough Market, near London Bridge, and drop our stuff off on the way back.

His name was Bill Wood, and he rented a Stable a few streets away from us, with a little Yard for the Cart.

I was home for the Summer Holidays, and of course I wanted to go to Market with them, and help in the Shop to earn some pocket-money.

I enjoyed my trips to the Market, and didn't mind getting up in the small hours. London was so quiet, with hardly any traffic before the Buses started running.

Bill's Horse was a Welsh Cob, Strawberry Roan in colour, named "Girl" or "Gell" as pronounced by Bill, who was a real Cockney of the old order, always immaculate in his tweed suit with Poacher's pockets in the jacket, cap, silk scarf or "choker", and brown boots.

Gell was a very intelligent animal with a mind of her own. Most mornings she was in a hurry to get to Market so that she could get her Nose-bag on, and would get a bit impatient at road-junctions if we had to wait. She knew all the horse-troughs on our route, and would snort and toss her head when we came to a corner near one if she was thirsty. Bill knew the signs and always let her have a drink.

Bill showed me how to hold the reins between my fingers and guide the Horse with one hand, and soon I was able to drive the Cart, under supervision of course.

I would meet Bill at the stable every morning and learned to groom the Horse, harness her up, and hitch her to the Cart, actually with a lot of help from "Gell", who knew exactly what to do, and would hold her head down while I slipped the collar upside-down over her head, then turned it the right way-up on her neck.

She would even back on to the shafts without being told while I held them up, pushed the ends through the slings and fixed the Traces. Soon, I was doing it on my own while Bill "mucked" the stable out and spread fresh wood-chips for the next night's bed.

Bill had trained Gell very well, he had a way with Horses as he was an old Cavalryman.

He never used the whip on her, but would let her know he had it by flicking it gently along her flank if she got the sulks.

I learned a lot about horses from him. He showed me how to look out for ailments and said "Always look after your horse and she'll look after you". When he showed me how to do something and he caught me trying a shortcut, he would say "There's only one way to do a thing Ken, and that's the right way!" I've always remembered that, and it's stood me in good stead.

I suppose it's not generally known, but Horse-food was actually on the ration during the war, at least oats and grains were. Hay-chaff was plentiful, but not much good for a working horse. We used to go to the Corn-chandlers every so often for Gell's

allowance of clover-chaff and oats, which was ample anyway. Every month, Bill was also allowed a bale of Clover, which had a lovely smell and was a treat for Gell. I don't know why, but horse-food was always referred to by the old cockneys as "bait".

Our way to the Borough Market took us across Tower Bridge Road, along Druid Street past the burnt-out roofless shell of St John's Church on the corner, it's slender white Spire with Weather-Vane still intact after being fire-bombed.

The first time I saw the gutted Church, surrounded by wreaths of mist at daybreak, I thought it was still smouldering. It was a very sad sight. The smell of damp, burnt timber that hit the nostrils as we passed was unforgettable.

Our route then led us into Crucifix Lane and St Thomas Street past the bricked-up Arches of the roads underneath London-Bridge Station that lead to Tooley Street.

These Arches were used as Air-Raid Shelters by the Residents of the many Tenement Buildings nearby. They thought they were safe, and used to sleep in them, but around 300 people died when the Stainer Street Arch received a direct hit through the Station at the height of the Blitz.

Later in the War, many more people sheltering in the Joiner Street Arch opposite Guy's Hospital suffered the same fate

It was a bit creepy, and I felt a bit uneasy going past these places in the small hours at first, but gradually got hardened to it and became fatalistic like Dad and Bill.

The "stand" for our Cart was right at the top of St Thomas Street between Guy's Hospital and the Borough High Street junction.

The trader's vehicles were tended by a Cart-Minder, who would direct the Market-Porters to the right vehicle when they brought the goods out on their barrows.

Our Cart-Minder was called "Sailor". He was a quiet old chap. You couldn't see much of him as he wore a stiff-peaked Cap over his forehead, and his face was covered in whiskers and a walrus moustache. He always wore a black oilskin coat down to his ankles, and rubber Wellington boots, perhaps that's why he was called "Sailor".

The Borough Market was a fascinating place to be at in the early morning before dawn. Because of the Blackout, the open-fronted Shops only had a small lamp at the back above the Salesman's desk.

My faourite place was the open Square behind the "Globe" Public-House, backing on to Southwark Cathedral. Here the Growers from the Farms in Kent and Essex had their Pitches, and did business by the light of Oil-Lamps.

There was always a lovely aroma of Apples, Plums and other Fruit round there.

I can still imagine the delicious scent of fresh-picked Worcester-Pearmains and Cox's Pippins even now.

The Growers didn't mind us sampling the wares, and I had many a good feed of fruit before Breakfast.

There was a Cafe in the other open Square known as the "Jubilee" behind the covered Market. Dad and Bill took me there for a snack when they'd done their business. The tea was always good, and the Sausage Sandwiches with Brown Sauce were out of this World.

Then I'd go back and wait on the Cart for the Porters to bring the goods out, and help load it up.

London Bridge and St Thomas Street was a very busy place first thing in the morning.

Swarms of People made their way down Borough High Street from the Railway Station, and many passed us in St Thomas Street on their way to Guy's Hospital.

I'd see a lot of the same faces every morning.

Guy's had already suffered a bit of bomb damage, but was still up and running, as it remained throughout the War.

In 1943, I had occasion to visit a friend who was injured in a road accident and taken in there.

The Wards were shored up with massive timber scaffolding to protect the Patients from roof collapse if there was a hit by a bomb.

I marvelled at this, one never stopped to think of the fact that bed-ridden Patients couldn't go to the Air-Raid Shelter, and there were hundreds of Patients in Guy's Hospital.

By the time the School Holidays came to an end, I was an old hand at looking after the Horse and helping in the Shop.

Luckily for me, Colfe's Grammar School at Lewisham had opened as the South-East London Emergency Grammar School for Boys who were not evacuated, and I was able to prevail upon my Parents to let me stay at home and go there.

I never saw Aunt Flo and her family at Torquay again, but George came round to see me a few times when he was home for the holidays, so I got all the news.

I enjoyed my couple of years at Colfe's, although it was a long Bus journey to Lewisham every morning, and I was usually late, because the Bus service was unreliable with hold-ups for one reason or another.

Because of the fuel shortage, some Buses towed a little trailer behind them carrying a gas-tank, and one of the strangest sights to be seen on the road was the Doctor's Car with a rectangular fabric gas-bag on the roof-rack billowing in the wind.

Things were a bit more free and easy at Colfe's than they'd been at St Olave's, and as we all came from different Schools, Uniforms didn't matter so much.

Some of us who came from a long way off, and needed School-Dinners, used to make our own way to the Convent at the top of Belmont Hill near Blackheath Village where our meal was waiting for us.

On the way up the hill, on the right-hand side of the road, there was a shoulder-height brick wall enclosing some open ground, and you could see over it across the rooftops below to Deptford and Bermondsey beyond.

One bright sunny day in 1942, while walking up Belmont Hill on our way to the Convent, my friends and I heard the sound of Aircraft engines and loud explosions. There hadn't been any Air-Raid Warning, but as we peered over the wall, we actually looked down on two German Planes swooping low and dropping bombs.

It was all so clear in the bright sunlight, like something out of a colour movie.

I could plainly see the khaki, green and yellow camouflage, the black crosses, swastikas, and numbers on the Planes.

I even saw the heads of the two crew-men in the nearest one as it turned after it's dive, with the sunlight flashing on the cockpit glass. Then the bombs exploded and smoke rose from below.

Just then, a shadow fell across us, and we heard loud engine noise as another Plane dived from behind us towards the lower ground, it's Machine-Guns chattering.

We crouched down close to the wall, hearing splinters flying, and as soon as he'd passed over, ran hell for leather up to the Convent.

This must have been the Plane that callously bombed and machine-gunned the School at Catford, close by Lewisham, where children were playing in the Playground at Lunch-time, and many were killed and injured.

I heard afterwards that Jerry had made a hit-and-run attack with Fighter-Bombers. Flying low under our Radar-screen, they caught our defences napping.

This was why there'd been no Air-Raid Warning, and the Barrage-Balloons hadn't gone up.

One of the bombs we saw being dropped landed quite near home. On a road-junction near Surrey Docks, known as the "Red Lion", after the name of a Pub on the corner.

It demolished the Midland Bank, killing the Manager as well as injuring Staff and Customers.

Also killed was the Policeman on Point-Duty at the Junction. He must have been blown to pieces, as only scraps of Uniform were found.

He was a Special Constable, a friendly man, and a familiar figure in the district.

He had a large Hook-Nose, which often had a dew-drop on the end in the Winter. Some people referred to him as "Hooky," and others as "Dew-Drop."

It was very sad that he went like that. If the Warning had sounded, he'd have taken cover.

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by ritsonvaljos (BBC WW2 People's War)

Introduction

A popular misconception about the casualties of the World Wars is that they were invariably young men serving in one of the branches of the Armed Forces. While this may well be true in the majority of cases, many civilians and young women serving in the Forces also lost their lives in the service of their country. This article is about a young servicewoman from Whitehaven, Cumberland (now Cumbria) who died as a result of World War Two.

Leading Aircraftwoman Elizabeth Cowan (known to her family as Betty) was one of the daughters of Walter and Elizabeth Cowan (née Ritson). Walter and Elizabeth’s other daughter was called Margaret. Although I was born some years after World War Two and thus have no personal memories of Betty, she was one of my father’s cousins.

When I was growing up and people used to tell me about Betty, it was obviously long before anyone was interested in recording stories about World War Two, so I never wrote these things down at the time. However, I have written this article based on what I can remember about what relatives have told me of Betty, a few family photographs and personal research. I would like to acknowledge the assistance of Mrs Enid McConnell, another of Betty’s relatives, for some additional information and photographs of Betty.

Serving with the WAAF

During World War Two many young women were required to do essential war work, including joining one of the Forces of sometimes factory work. Betty signed up for the Women’s Air Force. Betty’s sister Margaret Cowan was unable to join up because of a medical condition and so remained in the Whitehaven area during the war years. I believe that Betty went to the London area while she was serving in the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force.

Unfortunately, I do not have a copy of Betty’s Service Record. Hence I have been unable to trace the bases where Betty was stationed during the war, or what kind of work she did. At the time of writing this article (June 2005), the next of kin of a deceased service woman would be able to write for the Service Record. In Betty’s case, both her parents, and her sister Margaret have long since passed away, so that option is not possible either.

Nevertheless, Betty's kinswoman Enid has lent me an official wartime ‘Ministry’ Photograph of Betty with some of her colleagues at what looks like a briefing. Betty sent this photograph back home to her parents during the war. Although the photograph does not state where it was taken or the names of those in the photograph it provides some interesting visual information about Betty. On the back of the photograph it is stamped: “British Official Photograph No CH 7648 (Air Ministry Photograph Crown Copyright Reserved)”.

The photograph shows Betty in the 2nd row of what seems to be a lecture in an underground room during her training. Betty is standing up asking a question of a gentleman in a casual civilian suit who is facing the audience of RAF and WAAF personnel. He has his left hand in his trouser pocket.

I have checked the Imperial War Museum 'Collections Online' and found that this photograph does indeed form part of the ‘Air Ministry Second World War Official Collection’ (ID No 4700-16, CH 1-21587, includes CHX Numbers). It can be viewed by appointment with the IWM Photographs Department in London.

The IWM site says this collection shows the Royal Air Force in Britain during World War Two and includes operations out of Britain, aircraft, equipment, training and personnel. If the opportunity arises in the future to visit the IWM in London again, there may be some extra information about where and when this photograph was taken in the archives. Betty may even be in some of these other official photographs that I have never seen.

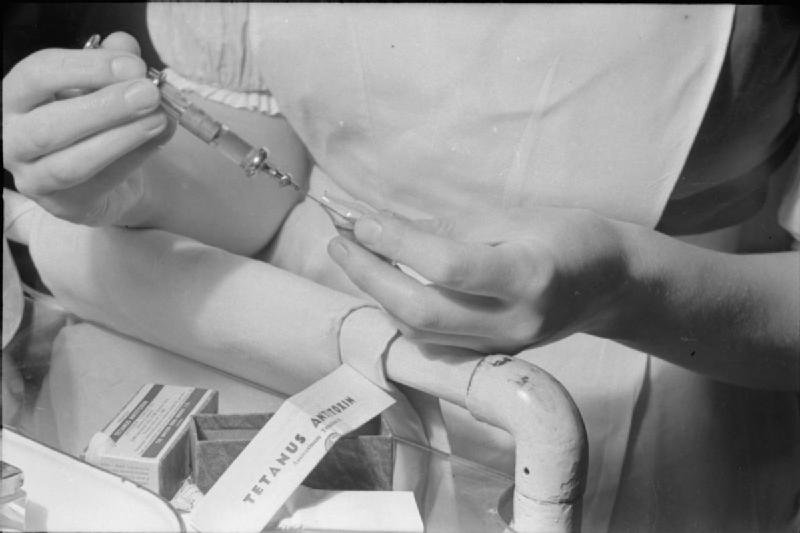

Bomb blast injuries

From what I have heard, Betty suffered ‘bomb blast’ injuries somewhere in the London area in the latter part of the war. Those of Betty’s relatives who would have known the exact details of how, where and when this happened are no longer alive to ask for further information. Betty died many months after being injured. We believe that a friend who was with Betty at the same time was killed, and that the friend’s name was ‘Daphne Pope’.

I have checked the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website to check for some details of Daphne Pope in 1944 or 1945 but I was unable to trace anything. There could be many reasons for this. ‘Pope’ may be Daphne’s maiden name and the one she was known by to Betty’s relatives in Whitehaven. If Daphne had got married during the war, the CWGC would use her married surname to record her death. Alternatively, I may not be using the correct spelling for the search. Nevertheless, I have included the information in this article in case it may lead to the correct information coming to light in the future.

Betty's worst injury was lung damage from the bomb blast, and it was this that eventually led to her death at the age of 30. By this time Betty had been discharged from hospital and was being cared for by her loved ones at home in Whitehaven. Although this was yet another tragic death of the war years, at least there is some comfort in knowing that Betty spent her last days with her nearest and dearest relatives.

I have a copy of Betty's death certificate (No 240, 1945, Whitehaven U.D.). Betty died on Wednesday 24 October 1945 at 10 Countess Road, Whitehaven, Cumberland (as it was then). The cause of death was listed as Asphyxia, Bronchial Asthma and Chronic Bronchitis. The doctor who certified the cause of death was Dr J. Tobin, L.R.C.P.

Betty's father Walter who was present at the time of death registered the death two days later on 26 October. The Deputy Registrar A. Ellwood issued the certificate. Walter was a Park Attendant by occupation, and this is also written on the death certificate.

Newspaper Notices

Betty was buried in Whitehaven Cemetery on Monday 29 October 1945 (Grave Reference: Ward 5. Sec. J. Grave 62). I visited the local Cumbria Archives Service Office in Whitehaven to see if the local newspaper, 'The Whitehaven News', had any additional information about Betty.

Often, there is a small article in the newspaper paying tribute to a local war casualty. However, the only references I found about Betty in the local newspaper were the obituary and acknowledgement notices inserted by Betty's family. These were in the edition published on Thursday 1 November 1945, and included below by courtesy of 'The Whitehaven News'.

Notices placed in 'The Whitehaven News' by Betty's family:

(a) In the 'Deaths' section):

"Cowan. - At 10 Countess Road, Bransty, Whitehaven, on Wednesday October 24 1945, Betty (ex-W.A.A.F.) dearly loved daughter of Walter and Elizabeth Cowan. Was interred at Whitehaven Cemetery on Monday, October 29th.

"At rest, her duty nobly done."

(b) In the 'Acknowledgements' section:

"Cowan. - Mr and Mrs Cowan and Margaret desire to THANK Dr Ablett, Dr Tobin, Nurse McCrae, P.C. Barnard, Mrs Walker and Mildred; also all kind relatives, friends and neighbours for letters of condolence and floral tributes received in their sad bereavement."

According to the newspaper obituary, it says Betty is 'ex-W.A.A.F.'. Betty is, of course, an official Air Force war casualty and the CWGC maintains her headstone and grave. In the acknowledgement notice, Betty's family thank the medical support team for their help. In those days, family, friends and neighbours in Whitehaven at least, provided more practical help to a bereaved family than is the case in more recent times. They would help wash and 'lay out' a deceased person, tasks that are now usually done by an undertaker. Mrs Walker and Mildred were next-door neighbours so this may have been what they helped with. I believe Betty's parents are thanking family friends and neighbours for this sort of practical help.

Betty is also commemorated on the Memorial inside St Nicholas Church, Lowther Street, Whitehaven. It commemorates those Anglicans from the parish who were casualties during World War Two. There are 20 names on the large Memorial Plaque inside St Nicholas Church Tower. Betty is the only woman whose name is on the Plaque, listed under her full first name of Elizabeth. At the top of the plaque it is written:

St Nicholas Church, Whitehaven

“Remember in The Lord those who gave their lives in the Second World War, 1939-1945”.

At the bottom of the plaque, after the list of names, the following Biblical quotation is written:

“In My Father’s house there are many mansions”.

Commonwealth War Graves Commission citation

As is the case with the St Nicholas’ Church Memorial, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorates Betty using her proper name of Elizabeth Cowan. Her citation on the CWGC website is as follows:

"In Memory of

Leading Aircraftwoman ELIZABETH COWAN

2096437, Women's Auxiliary Air Force

who died age 30

on 24 October 1945

Daughter of Walter John and Elizabeth Cowan, of Bransty, Whitehaven.

Remembered with honour

WHITEHAVEN CEMETERY

Commemorated in perpetuity by

the Commonwealth War Graves Commission"

The epitaph chosen by Betty's family to be written on her official CWGC headstone in Whitehaven Cemetery is: "At rest, her duty nobly done". These are the same words that Walter, Elizabeth and Margaret Cowan used when announcing Betty's death in the local newspaper. These six words convey such a lot about Betty's sacrifice and what she meant to her family.

Conclusion

I wish to dedicate this article to the memory of Betty's efforts and sacrifice during World War Two. I would have liked to have learnt more about Betty's time in the W.A.A.F. Once again, I would like to thank again the help of Betty's kinswoman Mrs Enid McConnell for her assistance in helping me write this article. Additionally, I would like to thank ‘The Whitehaven News’ and the Cumbria Archives Service for their help.

If there anyone who served with Betty during the war has any further information about her, it would be interesting to hear from them. Victims of World War Two should be remembered for something more than just a name inscribed on a headstone or a memorial plaque. I hope this article goes some way in doing that for Betty.

Elizabeth Cowan, R.I.P.: "At rest, her duty nobly done."

Contributed originally by Stockport Libraries (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People’s War site by Elizabeth Perez of Stockport Libraries on behalf of Mrs Margaret Boon and has been added to the site with her permission. She fully understands the site’s terms and conditions.

Friday 1st September 1939, a beautiful sunny morning and there I was, Margaret Webb, at the age of 9 years, standing on the platform at London

Fields Station in the East End of London, with my sister Joyce who was 4 years older, plus hundreds of other children. We were all agog at going on

this lovely train journey to God knows where. At that age we were very naive and didn't really understand what a war meant.

Most of our parents were there to see us off, double-checking that our name labels, which were tied to our coats, were secure and that we had our gas masks neatly packed in their boxes and slung over our shoulders, plus a case or bag containing our clothes and one or two personal effects. They, of course, also had no idea where we would end up. We finally set off about 9 a.m. with some tears, some fears, but a great deal of excitement.

After what seemed a very long journey, we alighted at a station called Thetford, which is in Norfolk (which we didn't know at the time). From there we were taken to a large hall, which I learned some years later was the Guild Hall. We were then given a mug of cocoa and a sandwich. A short

time later our names were called out and we were given a paper carrier bag each, which contained a tin of corned beef, some biscuits and one or

two other items of food, and put into various charabancs or coaches, as we would call them today. We were then dispersed in different directions.

After driving through the famous Thetford Forest and some beautiful countryside, during which time I had been sick (being a bad traveller and the cocoa probably didn't help,) we duly arrived at a village called New Buckenham, this was to be our final destination.

We were all bundled into the village school hall where all the local women were gathered. I cannot recall seeing any men there, apart from the two

male teachers who had travelled with us. Having arrived and feeling very nervous, we were well scrutinized by the waiting foster mothers - our

skirts were lifted to check our undies etc. Joyce and I were holding on tightly to each other as we had been given instructions by mother not to

be separated. Finally a lady asked if we would like to live with her and we were taken over to a Mrs Powell who was in charge of the billeting and

duly registered.

Mrs Tofts, the lady with whom we were to live, took us home to meet her husband and two daughters; Joy aged 7 and Shirley who was just 3. We were thrilled to find we were in fact living at one of the village shops (incidentally they made fantastic ice-cream). Everyone must have thought I was deaf because I can well remember saying pardon to everyone who spoke to me - I just couldn't understand their funny ways of talking. I had never heard the Norfolk dialect before. Mrs Tofts

then gave a basket to Joy and suggested she take us to the common to meet some of the local children and collect blackberries which she wanted to cook for our dessert after dinner.

On Sunday 3rd September, we attended church in the village and during the service we were told that war had now been declared with Germany. I'm afraid this didn't mean much to me as I thought war was a battle in a field just like the big picture hanging on the wall outside my old headmistress's office. I really had no idea that it could go on for years.

That night when we went to bed, my sister tried to explain it to me and was so convinced we would never see our parents again. I was far more

optimistic and I remember taking the sweet out of my mouth and giving it to her to suck just to pacify her and stop her crying. She was always

sensitive, whereas I was the tomboy of the family and wasn't going to let things like that worry me.

We wrote home to our parents and let them know where we were and told them all about our new surroundings and school and the many new friends

we had made.

One Friday evening, after we had been there about a month, I looked out of the window and couldn't believe my eyes. There was my Mum getting

out of a car. Oh the excitement!! What we didn't know was that she had written to Mrs Tofts, who in turn had invited Mum to come to New Buckenham to stay for the weekend to see for herself that everything was 0 K. During the weekend Mum went to see the billeting officer (Mrs Powell) and got a list of the names and addresses of the parents of all the evacuees in the village and, when she went back to London, contacted them and arranged a coach so that they (or at least one of them) could

make a trip to see the children on the first Sunday of every month.

Just before Christmas 1939, Mr Tofts was taken ill and at the same time his two daughters went down with chickenpox. As Mrs. Tofts had the shop to run as well as look after her sick family, this meant that we had to move and leave the home we were getting nicely settled in and find somewhere else. Unfortunately no one could take us both together, but we found billets next door to each other. Joyce went to live with Mrs Smith on the other side of the village green and I went next door to live

with Mr & Mrs Brown.

Mrs Brown was very strict and extremely houseproud so I had to watch my step. However she was a wonderful cook. Mr Brown (Ronald) was a farmer, a churchwarden, a member of the Royal Observer Corp and a very respected member of the community and I loved him from the start. He had the most wonderful giggle and when the two of us started it drove everybody mad. We always had a lot of fun together. My own father had always been very distant with me and I can never remember him giving me a cuddle or sitting on his knee. Whereas Mr Brown was entirely opposite, so I suppose it was only natural that I came to regard him as my true dad in every sense.

I had only been with the Browns for three days when I woke up and found my body was covered in spots and blisters. I'd caught chickenpox. As it

was Christmas Eve this meant we could not spend the festive holiday with Mr Brown's parents, which was the usual custom, as I was confined to my bed. As Mr Brown was so determined that I should be kept amused he climbed up into the loft and brought down his mandolin which he had brought back from Greece at the end of the First World War (and incidentally never played since) and tried to keep me happy by playing lots of tunes (not too well I'm afraid). Even though I was feeling pretty ill I can tell you we had plenty of laughs.

The farm was just outside the village, but I spent every spare minute there. I may have been a Cockney but I was a true country lass at heart.

I took to the life like a duck to water. I would feed the hens, muck out the cattle, brush and groom the three beautiful shire horses. The largest was Captain and he was huge. Next was Blossom and then my favourite, the smallest one John. I helped with the haymaking and harvest and the threshing and adored every minute.

One day in Autumn, when I was leading one of the horses pulling a cart load of sugar beet I wasn't watching where I was going and the horse ended up standing on my foot. Not knowing any different I tried pushing his body to get him off. He knew better than to be pushed off balance so trod down all the harder. It was only when one of the farm workers saw what was happening and picked up the horse's hoof by the fetlock that I realised how easy it was. Fortunately no bones were broken, but my foot was badly bruised and swelled up like a balloon and stayed that way all the week. I didn't blame the horse - it taught me a valuable lesson.

Mr Brown also owned a couple of orchards and round about September time each year we gathered all the eating apples, cooking apples and pears in bushel baskets and took most to market, either in Diss or Norwich. As he was a farmer and an important citizen he was allowed a certain amount of petrol. I couldn't believe it when I first saw his car - wow! It was a navy blue Rolls Royce.

Whenever we went into the town, Mrs Brown always asked if I wanted to stay with her and go round the shops or would I rather go with Ronald and yes, of course, I always preferred to go with him. He took me round the museums and the cathedral and in the winter we mostly ended up at Carrow Road in Norwich to watch the football. I suppose this must have

caused a bit of jealousy, but at the time I didn't realize it.

Mrs Brown always went out on Wednesday nights to play whist somewhere in the village and did not get back until around 10.00 p.m. She gave strict

instructions each time that Ronald should make sure I was in bed by 8 p.m. Once she had gone we got out the cards and he taught me to play rummy, Newmarket and crib. Naturally as we were enjoying ourselves the time just flew and often we would hear the back gate and I would fly off to bed just before she came in. On entering I would hear the same old question "Did she go to bed on time?" and the answer "Of course Maggie." and I would be giggling under the bedclothes.

In September 1941, I had to go to the school in the next village now I had attained the age of 11 years. Old Buckenham School was just over 3 miles

away and of course much bigger. For the first few months we had to walk there and back, no matter what the weather and that winter was one of

the worst on record. Deep snow drifts and the snowploughs were brought out to clear the roads. I developed enormous chilblains on my feet and

the backs of my legs, but I still got to school every day and on time. There was quite a crowd of us that used to go together which made it all

the more enjoyable.

Eventually the Norfolk County Council gave us all bikes, which we had to take good care of. Our headmaster held an inspection every week to check that we had cleaned them and everything was in order. If we were caught playing around on them or giving someone else a lift they would be taken away, so we were always very careful to keep within the rules. We were taught how to mend a puncture and put the chain back on and pump the tyres up to a certain standard and clean and polish them so they

always looked like new. Extremely proud of our bikes we were - never had anything like it in our lives before. Sometimes at weekends during the

summer I would go out with Mr and Mrs Brown round the countryside on our bikes.

By this time my sister Joyce had already returned to London, having reached the age of 14, and also because she was suffering from asthma and needed hospital treatment.

When I first went to live with the Browns they had a beautiful cat called Peter. Although I have never been a cat lover, something about this one

appealed to me. Maybe it was because he was so friendly from the start. He had a lovely pure white front and the rest of him was a kind of pinky-

ginger. He really was a great big bundle of soft cuddly fur. I spent hours grooming him, while he purred loudly with contentment.

One day I decided to give his whiskers a trim and he sat there quite happily while I cut them back to about one inch on each side. When Mr Brown saw him, he was horrified and that was the only time he scolded me. He went on to explain that the whiskers on animals were used as a measuring device. By putting them against a gap, the animal knew whether the rest of his body would go through -Lesson No. 2.

After I started at Old Buckenham School I developed a habit of stopping off at the farm gate and giving a long whistle. If the horses were not working they would come in answer to my whistle. Invariably John was always the first. One afternoon in late Autumn, I stopped as usual and

could see John lying down in the next meadow. As he didn't respond I got worried and raced off to find Mr Brown to tell him. It transpired that

poor John was so old and had collapsed. The kindest thing was to have him put down. This really upset me and I cried buckets. It's hard for an 11 year old to realise that this was for the best. I had regularly taken all three horses down to the village blacksmith to be shod, and I loved the warmth of his fire, especially on cold winter days.

I had many friends in the village and when not on the farm we used to go on to the common to play. I must admit when the boys were playing cricket I used to steal their ball and get chased and sometimes thumped for my cheek. I was also a bit of a rogue on the farm and tormented the poor farm workers. One day after we had mucked out the cattle sheds and had a nice big pile of warm manure, they got so fed up with my torments they grabbed me by my legs and arms and threw me on top of the pile. I was only wearing a little top and shorts. By the time I climbed off, I stank to high heaven. Mrs Brown was not best pleased when I

arrived home.

Mr Brown Senior, who was my foster grandfather, had a pony called Peggy and a trap, which he took great pride in. Always polishing the wood and brass until it shone. I felt very privileged when he taught me how to drive the pony and allowed me on one occasion to take the reins on a return trip from Diss. I was so proud I felt like the lady of the manor.

Grandfather Brown used to grow grapes under his veranda in the garden, which were his pride and joy. On one occasion when I was playing out

there, I looked up and saw these enormous bunches of grapes hanging down just above my head so I reached up and pulled a bunch down. I was

sitting enjoying these lovely juicy things when I received a cuff around the ear. (The one and only time in my life) - Lesson No.3 - Never take

something which doesn't belong to you without asking permission.

Late in the year of 1943, Mrs Brown informed me that my Mother was coming the next day to take me back to London. I was completely stunned

as I was prepared to stay for the rest of my life and couldn't understand why I had to leave. No explanation was given to me.

On the day of parting both Mr Brown and I were heartbroken. My Mum told me later that Mrs Brown had written to say she could no longer cope and suggested I should come back to London. As she never did tell Mr Brown the reason he naturally thought my mother was to blame. I can only assume on looking back that she must have been jealous because we had grown so close. Mum thought it might have been because she didn't know how to handle things as I was becoming a teenager and it might mean a lot of explaining. However I did write to them regularly and was invited back each year for a two-week holiday, but of course the closeness between Mr Brown and myself had been broken and I must confess I found it hard to forgive Mrs Brown for that.

Anyhow I was determined not to lose contact and when I was to be married in 1953 at the age of 23, I not only invited them both to my wedding, I asked Mr Brown if he would do me the honour of giving me

away (my parents by this time had been divorced). I don't think I have ever seen such pride and pleasure on a man's face as I did that day. I

thought his speech at the reception was never going to end. To cap it all we went back and spent our honeymoon at my old home in New Buckenham.

Mrs Brown died a few years later, having suffered from diabetes for some time. I discovered she had never told Mr Brown the truth about my departure and I didn't feel it was right to enlighten him.

As he had always been a busy farmer and never had to do cooking or housework he was completely lost and eventually his brother found a neighbour who was widowed and was willing to move in to the house in New Buckenham and become his housekeeper. Eventually they were married and I must say, Grace, the second Mrs Brown was an entirely different

personality to Maggie. She was homely and had a lovely sense of humour and I got on very well with her. I still went for holidays occasionally but

Mr Brown's health gradually deteriorated. Then at the beginning of the '70s I received a letter from Grace telling me he had died and I knew I had lost a true and lovable friend.

I still keep in touch with Grace, even though it is now 2004 - some 60 years or more since I first went to New Buckenham. She is now in poor health and in her late 80's.

I also regularly keep in touch with one of my old school friends, who is 4 years older than me, who was also an evacuee and married a Norfolk man

at the end of the war and settled in Thetford. It was in fact Florrie who organised a celebration for some of us together with the villagers after

50 years. We went back each September where we had a church service and called on some of the village folk that we remembered.

We also had another celebration after 60 years in the village as well as attending a march and special service organised by the Evacuees

Association, in Westminster Abbey. This was supported by hundreds of ex-evacuees from all over the country which included many famous names.

I wrote a poem for each of the 50th and 60th celebrations which were printed in the New Buckenham parish magazine. Copies of both have also been lodged with the Imperial War Museum in London.

As I spent so many happy years of my childhood in Norfolk being loved and cared for, I still class New Buckenham as my home.

Contributed originally by Allen Bowtell (BBC WW2 People's War)

MY TEENAGE WAR YEARS:Evacuee Early Years by AllenBowtell.

In June 1939 I became a teenager, at that time war clouds were gathering over Europe, but to a thirteen year old this did not mean a great deal to me. Most of the boys of my age were still wearing short trousers and did not go into long ones until the magical age of fourteen. When the school that I was attending at the time, John Harvard Senior Boys School in Southwark, London, broke up for the Summer holiday I was looking forward to spending two weeks away at the seaside. The early part of the school holiday period was spent playing with my friends in and around the area we lived.

My two brothers and I lived with our parents in a three-storey house in Great Suffolk Street, Southwark, London. The house was within walking distance of Blackfriars, Southwark and London bridges. and the City of London. lay on the other side of the river. On the ground floor of our house was a newsagent shop with a room behind which served as a place to eat when the shop was open and a work room for carrying out the tasks required to run the shop. My father was the newsagent and my mother helped in the shop in addition to running the home. The first floor consisted of our lounge or 'front room' as we called it and the room behind was a living / dining room. Between the two rooms there was a double door that we opened when we had a party to make one large room. On the top floor there were two bedrooms, my parents used the front room and my brothers and I occupied the back room. In addition to these rooms there were two rooms below ground level, the basement we called it. One corner of the back basement room was occupied by a brick built solid fuel boiler or 'copper.' The floor in both rooms were made of cement paving slabs. There were two main purposes for the back room, a place for my mother to do the clothes washing and our bathroom. The clothes washing had to be done by hand in a tub using a scrubbing board and boiling in the copper. In those days there were no washing machines in general use as there are now. With regard to the days when a bath was required, this had its own ritual. First the water had to be heated in the copper, then ladled out into a galvanized iron bath that measured about 4.5 ft [1.37 m] long. When we had finished our bath we had to step out on to a towel which covered the cold floor. The only consolation was the fire burning under the copper which took the chill off the room. Normally when not in use the bath hung on a nail hammered into the wall. In the front basement room my father kept this as a store room for the items to be sold in the shop. The front part of the room was used as a coal store, which was filled through a hole in the pavement in front of the shop. On the ground level at the back of the house was a yard measuring about 25 ft [7.75m] x 20 ft [6m] surrounded by brick walls. In the corner of the yard was our only toilet, this was a very cold place to be in the Winter.

On the 3 September 1939 the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain announced on the wireless or radio, that the Country was at war with Germany, my father and I were on holiday at Weston super Mare in Somerset. At this time my mother was looking after my two brothers and the shop in London. Because my father thought it would be too dangerous to take me back to London with him, he arranged for me to stay with a family in Worlebury, Weston super Mare. This was to be my first day as an evacuee. Meanwhile my two brothers, Raymond aged 9 years and Derek 6 years, were evacuated with the rest of their school, Charles Dickens Junior, to Hove in Sussex. This unhappy situation caused our family to be split up for a period of time with many miles between us.

The man and his wife who were to be my foster parents lived in a semi-bungalow. Upstairs there were two bedrooms and the bedroom I was to use had a window overlooking the bay where I had been staying during my holiday. In addition to my foster mother and father, the family consisted of three sons who were serving in the Army as regular soldiers and three daughters, a school teacher, a nurse, and the third one was working for a family who lived close by. One of the first things my foster parents had to do was to find a suitable school for me to attend, because my London school had been evacuated to another part of the country. The school which they decided would suit my needs was in the centre of the town, it was called Walliscote Road School. To get there I had to travel by bus, a journey of 4 to 5 miles from where I was living. It was strange at first as all my classmates were local children and most of them spoke with a Somerset accent, this I found a little difficult to understand at times. Before long I soon lost some of my London way of speaking and began using the local dialect like them.

During my stay in Weston I joined the local Scout group and as the Scout Leader had a large garden he encouraged me to attempt to pass the gardening badge. This was something I would have had great difficulty in doing in my London group as the largest garden anyone had in that area was a window box. In addition to belonging to the scouts I joined the St. John Ambulance Brigade cadets. As there was always a chance that an air raid could occur and people injured, we were taught first aid especially for those injuries most likely to be caused by bombing. On one occasion a full scale air raid exercise was carried out with the cadets acting as casualties. Labels were pinned to our clothing indicating the type of injuries we were supposed to have. These mock injuries were attended to by the adult members of the St. Johns or the Civil Defence workers. We then had the experience of being taken at great speed to the hospital in a 'utility' ambulance. These ambulances had been built as an addition to the normal ones, for use when the need arose in times of emergency. They were about the size of a large car but had a canvas covered back and fitted out to carry four stretchers inside. Being a casualty on the top stretcher was like sailing in a small boat on a choppy sea and we were very glad when we reached the hospital with only our mock injuries. On our arrival the doctors and nursing staff were waiting to check the handiwork of the people who had attended to the injuries mentioned on the labels.

Another way in which the war affected the people, was the introduction of food rationing in January 1940. After school and on Saturdays I used to help at the General Store at the end of the road. One of my jobs was to make up the small quantities of butter, tea, sugar, etc., then deliver the groceries on a bicycle made for this type of work. The bicycle had a large box on the front with a small wheel underneath and a normal size wheel at the back. It was a little difficult to ride at first until I got used to it. The front wheel seemed to have a mind of its own when the box was loaded. The wheel wobbled from side to side like a mad thing and made it hard to steer. This job provided me with some pocket money that I saved to buy my first bicycle, a second hand one, of which I was very proud. It cost me ten shillings that is fifty pence in present day money.

You will remember my bedroom overlooked a bay, this was called Sand Bay. On the far side of the bay there was a strip of land jutting out into the sea, the tip of this piece of land was called Sand Point. In peace time people were allowed to walk on this headland which was a favourite spot for bird watchers. Now it was a restricted area because the Royal Air Force was using it as a firing range for machine gun practice. The aircraft they used at that time was the Gloucester Gladiator fighter. These aeroplanes were very slow compared with todays aircraft. However, it was quite an experience to see them dive down at full throttle, with their machine guns chattering away at the targets on the ground.

During the first year of the war there was very little enemy air activity over London or the rest of the country, as a result of this unexpected period of quiet it has often been called the 'phoney war'. Many people had been lulled into a false sense of security during this period, this included my parents. They decided when the Summer holidays in 1940 came along it would be safe for me to return to my home in London for the holiday. We did not realize that this hot and sunny Summer was going to be the start of what is now called the 'The Battle of Britain' and of course 'The Blitz'.

In the month of June I reached the age of 14 years and like most boys of that age and younger I used to wear short trousers. After the holiday I was due to return to Exeter in Devon because I was going to join a school from my part of London called the Borough Polytechnic. This meant having a new school uniform which included my first pair of long trousers. All these clothes were neatly folded and put on the lounge table ready to go into my case when I was due to set off for Exeter. Unfortunately it was not going to be as simple as that, because the German Air Force had other ideas.

At the early part of August 1940 the Luftwaffe started bombing our aerodromes, to make them unserviceable as a prelude to an invasion of England. This was the start of the Battle of Britain. As these attacks on the R.A.F. bases were not having the desired effect they left those targets and on the 7 September the 'Blitz' on London started. On this day the sirens sounded and shortly after I could hear the drone of a large number of aircraft. From the outside of my house I was able to see wave upon wave of German bombers heading for the East End of London. On reaching their target they dropped hundreds of high explosive and incendiary bombs on the docks and buildings around the dock area. When the raid ended great pillars of smoke could be seen and the sky a bright red caused by the raging fires. The air was filled with a strong sickly smell which gave a clammy feeling of evil in the atmosphere. At first when the sirens sounded my parents and I went downstairs to our basement and used it as a makeshift shelter. After the first night our next door neighbours persuaded us to use the shelter across the road which was in the basement of a block of flats called Queens Buildings. It was just as well that we did because on the night of the 9/10 September there was a terrific crash from a bomb that exploded in the vicinity of the building in which we were sheltering. The noise awoke me and I found that the other people and I were lying amongst a great deal of broken glass that came from a window above the door. Luckily I was not cut from the glass, but a greater shock awaited my parents and I when we left the shelter in the morning. Instead of our home and shop, all that remained was a pile of rubble made up of bricks, mortar and the contents of our home. When my father tried to get near to the scene of destruction to salvage anything of our belongings, the Air Raid Wardens prevented him saying, 'there was an unexploded bomb [UXB] buried in the rubble'. My mother was heartbroken when she saw the devastation and to make matters worse she could see a teddy bear belonging to one of my brothers sticking out of the wreckage, but she was not allowed to get it.

Contributed originally by caroleleeds (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story is about my grandfather, Reginald Parkhouse, who died in 1972. My father found a diary he had written during the war years, and in particular about events in 1938. My grandfather had served with the Middlesex Regiment in the First World War and was a member of the British Legion. When Hitler threatened the Sudetenland, Churchill wasn't the only one who was worried, the Legion were too. They canvassed their members and agreed to send over a civilian police force to help the Czechs and repel the Germans. They were entirely volunteers and my grandfather was one of them. They were issued with armbands and a short stick and about 1,000 men signed up. My grandfather and these other men marched down to Tilbury and there was a ship waiting there (I don't know where it was headed as to my knowledge Czecheslovakia is landlocked!). However, they stayed on board at Tilbury for a couple of days and caught up with gossip; some of these men hadn't seen each other since the end of the Great War. Finally, they received notification in the form of an official letter from Lord Halifax to say that they would not now be needed as the British Government had assurances that the invasion would not take place. Sadly, as we all know, these assurances were fictitious. It's a great tribute to these brave men that they were prepared to go to a foreign land, totally unarmed, to help a defenceless civilian population. My grandfather had kept his armband, stick, letter from Lord Halifax and a cutting from the Picture Post which showed them marching towards the docks, and I took these down to the Imperial War Museum some years ago. They did not have any knowledge of this strange incident, but have now opened a file on it for anyone to read about. Hope people find this interesting. Carole Parkhouse

Contributed originally by JohnCopley (BBC WW2 People's War)

Many Lamprell streeters were formerly convinced that it was that barrel store that had caused all the trouble in the first place.

We’ll never know. Perhaps some Luftwaffe gent did mistake those thousands of empty fifty-gallon drums for a tempting oil refinery.

Equally likely, he simply wanted to unload and go back home. The only certain thing was that his stick of bombs narrowly missed the barrels and flattened the top half of Lamprell Street instead.

It was some time after this that my Dad decided to organize street A.R.P. patrols. The phrases ‘bolting horses’ and ‘stable door’ do spring to mind perhaps. But then, during those hectic days, the fact that you’d been bombed once was no guarantee that you couldn’t be again.

He was a character, my Dad. Best bloke I’ve ever met. Best father anyone could ever have. Pity he never wrote really. Because he was a born verbal storyteller. I grew up listening to his tales. Glad of it too. They enriched me. Just as he did.

Aged seventeen, fed-up with starving, he’d enlisted. His timing a shade unfortunate. Namely, June 1914. Found himself in a remote outpost called Exeter, Private Copley, James: 6068 Devon Rgt. For a few weeks, wore the flash red tunic and spiked helmet of that era.

Until a huge war broke out. Red tunics disappeared for good. So did much of an entire generation. Dad was one of the lucky. Limped for the rest of his life, but alive and holder of the coveted D.C.M., to boot.

Anyway, one of his numerous talents was an ability to be very persuasive. He could talk almost anyone into doing almost anything. But even he could sometimes come unstuck. As he discovered, when he tried to kid the barrel store owner to donate a couple, to be filled with sand, handy for subduing fires.

I only heard about their conversation at secondhand. It seems to have gone rather upon these lines:

Barrelman: “Yeah, can ‘ave a couple. Ten bob each.” (Translated into 2003, fifty pence. A trivial amount now. But quite a large one in 1940).

Dad: (furious) “What!” Ten bloody bob! When you’ve got thousands of ’em? When we’ll be protecting your place ’n all?”

The owner was stubborn. Dad came away barrelless and angry, at what he considered a mean injustice. It wasn’t just the money. There was a lot of pride, principle at stake now. The rather flexible moral code of that time and area demanded that barrels must now be pinched.

Though Bill Cadd wasn’t enthusiastic, not when first approached. Nice bloke Bill. Lived roughly opposite us. Easy-going, but preferred a quiet life.

“Ah no Jim,! he said. “Can’t go pinching ’em, can we? What if we get caught?”

“Ah don’t worry,” said the Svengali of Old Ford airily. “We won’t be. I was doing trench raids when you was still sucking jelly babies. I’ll look after you.”

As I said dad could be persuasive. In the end, he even managed to enlist this reluctant confederate. And so, the early hours of a freezing cold morning saw these two stealthily scaling the Everest of drums.

Most likely, there would have been an air raid in progress. There was one almost every night then. If so, the noise of it could have been useful; covering any racket they made. But even the Luftwuffe couldn’t drown all the din they created. Not when they carelessly allowed a barrel to slip and career down the pile. An empty fifty-gallon drum, bouncing its way off dozens of other empty drums is fairly audible. People all around may have heard. Wondering, at this strange racket.

“’Ere! Hear that? Must be some kind of new bomb.”

Dad and Bill descended the pile soon after the barrel did, appalled by the ear-splitting din it created. Reached the bottom and hastily parted company. Bill rapidly towards his own house, dad, who hadn’t been able to run for over twenty years forced to lie doggo amid bombed ruins.

Soon afterwards, two elderly and muttering watchmen emerged. Using the shielded and pretty useless torches of the blitz era. They weren’t alone. Bob was with them.

We kids rather liked Bob. He was some kind of Labrador I believe. Quite old, but quite hefty. He looked dangerous. But after earlier caution we’d learned; he was a big old pussy really. Seemed to love all people, especially kids. In short, a nice old mutt, but hardly an ideal guard dog. By now, his sense of smell was probably about that of a house brick. These three mooched around for a while, as Dad lay doggo. Poor Bob probably simply wondering why he’d been dragged out in the cold. Maybe the two old boys were wondering why they were out in it too.

Once they’d gone, Dad got one of the mad ideas he sometimes did. “Hey! Bet old Bill’s indoors now having kittens. Yeah! Yeah, I'll burst in on him. Gee him up a bit.”

The terraced houses of Lamprell Street shared a common brick wall at the rear of each tiny back garden. With some difficulty, Dad scaled this and began crawling along it like a cat, until he reached Bill Cadd’s section. And with even more difficulty, descended into Bill’s garden.

His luck was in. As he’d hoped, poor Bill had retreated into the kitchen, as far away from his front door as he could get. Still shaken, gnawing his fingernails down to the first knuckle. Expecting any moment that the Sweeney would burst in on him. Instead, Dad burst in.

“Right Cadd! You’re nicked!”

Telling us later, Dad swore that poor Bill rose vertically in the air, whinnying in pure terror. Bashed his head on the ceiling, and came down, his face ashen.

“Christ Jim! Whay’yer doing? Could have give me a heart attack there.”

“Oh sorry,” said Dad, with massive insincerity. A few more placating phrases, to allow Bill to calm down, then:

“Anyway: fit to try it again?”

“What?” Bill was astonished. “Go back there? What, now you mean?”

“Yeah. Best time to do it. After that last do, they’ll never be expecting a second one, same night. Don’t worry. I’ll look after yer.”

Bill may have reflected that he’d already heard this airy promise once tonight, and that it hadn’t worked out too well. He wasn’t keen to see it tested again, but eventually gave in.

Their second expedition was quieter, more careful, than the first. Two barrels were quietly snaffled and wound up in our back garden. Dad never hung about. By the next day, the barrels were painted. Top and bottom sections red, middle one white, to show up in the blackout. While a gang of us kids had been detailed to bring sand. By that afternoon, they were in the street, all ready to be used.

The barrel store owner had probably got to hear about this over the grapevine. I’d suspect that both he and Dad enjoyed the chat they had. Both East enders: with a weakness for this sort of situation.

“See you got yer barrels after all then,” said the owner affably.

“Yeah. We was lucky there.” Dad, deliberately making his account as unlikely and implausible as he could. “Heard about this bloke up Cadogan Terrace. Had a couple he wanted to get rid of.. ‘Oh, oh,’ he was saying. ‘If only someone would come and take ’em away for me.’ So we did.”

“Hmm, lucky.” the owner rubbing his chin to conceal a smile. “You know; someone tried to nick some of ours last night.”

“Oh Gawd!” Dad was the most shocked man on the planet just then. “Some of ’em will pinch anything.”

The owner knew of course, that he was speaking to one of the culprits, Dad knew that he knew. In turn, he knew that Dad knew he knew. But by then neither of them cared much.

“These two look just the same as ours,” said the owner casually.

“Well, yeah. All look much the same, don’t they? None of yours are red an white are they?”

“No.” the owner agreed. He casually touched the nearest one. Then stared at his fingers, which were now bright red. “No. We don’t have any red ones.”

He’d turned out to be a good sport about it after all. Those drums remained in place for five more years. Never used. No more bombs ever fell directly upon the remaining half of the street. I don’t know what became of them afterwards. Most likely, they were simply junked, along with most other redundant wartime stuff. Gas masks; stirrup pumps; steel helmets. It all went. In the euphoria that followed the war being over at last, nobody wanted reminders of it hanging around.

Pity, perhaps. Some of it might in time have become prized relics. Even better luck, our barrels might now be on show in the Imperial War Museum. As a little bit of British history.

Contributed originally by Blue Anchor Library, Bermondsey, London (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Marion McLaren of Southwark Libraries on behalf of Fred Newman and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Southwark Family Memories of WWII

by Fred Newman

In the days before the start of World War II, under the supervision of my father who was incapacitated, my two brothers who were aged twelve and fourteen and myself aged sixteen, dug out the earth in our back yard and put in the Anderson shelter – our cousin who lived with us also helped until he was called up to join shore gun batteries near Lyme Regis. On the day Neville Chamberlain said that we were at war with Germany, Dad, with his experience of gas warfare in WWI, told us to fill our long galvanised bath with water and put by its side enough blankets to cover every window, each one of which had already been criss-crossed with transparent masking tape. The air raid siren sounded just after the Prime Minister’s broadcast and my brothers and I set to soaking the blankets and putting them up at the windows. I think that we were shaking with fright and near to tears Mum and Dad putting a brave face on things. Thankfully, it was a false alarm. A week or so later both my brothers were evacuated to Seaford – neither wanted to go – luckily they were billeted in a mansion and very well looked after. Unfortunately, the owner of the mansion fell ill and my brothers were re-housed - both had to work for their keep, the younger having to collect and chop wood for the fires and clear and clean the grates etc. and the elder had to work on paper rounds and give up the money. After a while they plucked up courage and , unbeknown to the householders, sent a message home saying “Come and fetch us home straight away or we will run away and walk home”. Mum and Dad had to make sure that their gas masks and suitcases came with them. The elder brother eventually gave up a university place to become a Paratrooper. A Green - a stick fracture made him drop out to become a Medic (still having to drop from the sky) in National Service. I worked at an engineer firm and had to join their fire watching team, and with a team mate had to take a turn at the top of the building fending off the incendiary bombs (from parts of the roof) with long handled shovels and sticks. I also joined the “Home Guard” – we had manoeuvres around the streets of Southwark, using ‘half bricks’ as substitute ‘hand grenades’. We had rifle practice at Bisley. Sad to say I was not a good shot which was confirmed when I joined the Navy as H.O. when the officer thought me so bad that I must have had a faulty rifle. Fortunately, I finally served in the Navy as a Wireless Telegraphist - some time in 1941 I think. When the Elephant and Castle was bombed, I had to go into Guy’s Hospital to have my appendicitis taken care of. The nurse who removed the clips after my operation was Haile Salassie’s daughter. When back on home guard duty our patrol went, we thought, to assist an old man who’s house had just been holed, as it turned out, by an unexploded bomb. He, thinking that we wanted to loot his house, chased us out branding a big carving knife. The cousin who was in the Gun Battery in Lyme Regis had to act as cook when the main cooking staff all went down with the ‘flu. The Commanding Officer had arranged a special dinner party in the Officers’ Mess and my cousin had to cope without assistance. The Orderly Officer decided that the pudding should be plum duff and custard. Reading the instructions which said “a pinch of salt” but knowing that many portions were required, three handfuls of salt were put in. Tasting same proved to be horrendous so a large tin of cocoa was added to mask the taste. Expecting to be placed on charge when he was summoned to the Commanding Officer’s presence, my cousin was surprised to be asked for the recipe so that it could be passed on to the C.O.’s wife! Likewise, on the way home from the Med on an ocean-going mine sweeper, Jaunty said “Sparks, you will be cook tomorrow”. “Sparks don’t cook” said I. “He does on this ship, we all take our turn except the Captain and me” says Jaunty , and “”we want stew and dumplings”. That stumped me. I could cook the meat, etc., but dumplings – I did not get the mixture right so they finished up as hard as bullets and they bounced off the bulkhead when the crew missed when throwing them at me, as we went through the Bay of Biscay.