Bombs dropped in the ward of: Newington

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Newington:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 93

- Parachute Mine

- 2

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Newington

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

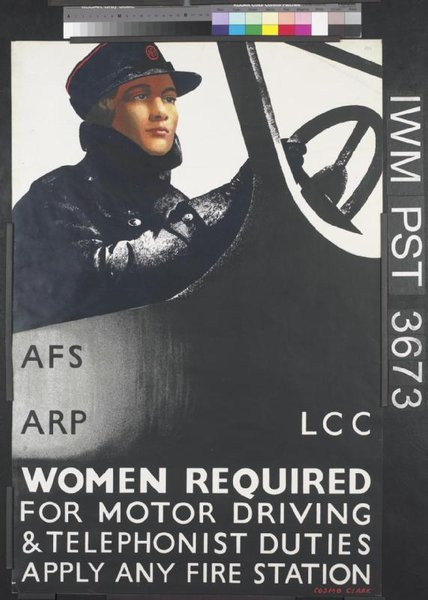

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!