Bombs dropped in the ward of: Riverside

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Riverside:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 134

- Parachute Mine

- 2

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Riverside

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

I arrived home at Bermondsey from Torquay in 1941 to find that things had changed dramatically.

The Shop-windows were still plate-glass, but all the window-frames of our House were covered in opaque plastic, which only let a little light in.

I was the last one to come home.

My eldest brother John, had left School and was now a GPO Telegram Boy, with blue uniform complete with red piping, Pillbox Hat and red Bicycle.

Percy took his place at the Borough Polytechnic, a Technical School in Southwark, so he was settled.

Iris and Beryl had also come home from Exeter, as they were unhappy there, and were back at the local Junior School, which was open again.

However, the biggest change was in the Shop, and to explain things properly, I must digress a bit.

At the top of Galleywall Road where it joined on to Southwark Park Road was the "John Bull Arch", named after the Pub alongside it.

It was (and still is), a wide brick-built Railway Arch with steel girder framework over the roadway on each side, carrying many of the lines into London-Bridge Station from Kent and the Suburbs.

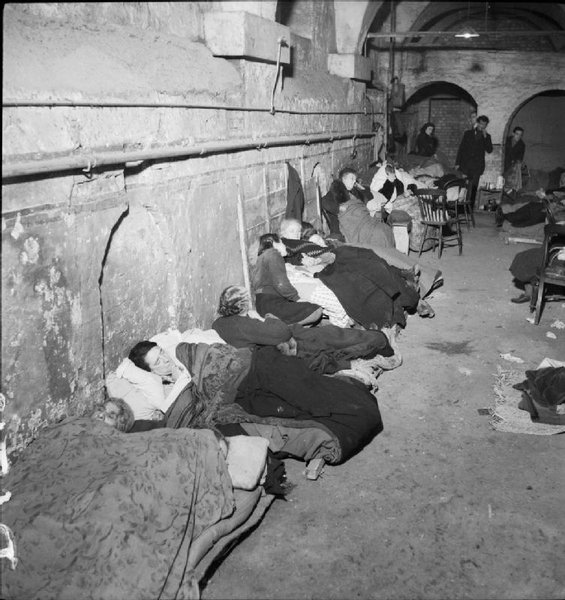

There were paved foot-tunnels either side of the Roadway.These had been bricked-up at each end, and were used as Air-Raid Shelters.

They were fitted out with bunks, and many of the local people who didn't have a Shelter at home slept there every night.

The Arch suffered a direct hit on Sunday 8 December 1940, and over a hundred people were killed, including most members of a family who lived across the road from our shop.

One of them was a boy about my age, Charlie Harris, who went to my School before the war.

Recently, while doing some research on my Uncle, who was missing in WW1, I found that the War Graves Commission has a Civilian War-Dead Register, and there, sure enough, I found Charlie's Record of Commemoration. To read it made me feel very sad, but it's good to know that Civilian Casualties aren't forgotten altogether.

That Arch was a very unlucky place, apart from more near misses with casualties in the bombing, there were two direct hits on it by V2 Rockets in November 1944. The first one was on a Friday Morning. It demolished most of the Arch and devastated the area. Two Sundays later, when the wreckage had been cleared and a Temporary Bridge put up, another Rocket landed in exactly the same place, so the Workmen were back to square one, and we lost many more Friends and Neighbours in both incidents.

But back to 1941.

Along by the "John Bull" Pub, there was a large Greengrocer's Shop, which also sold a bit of Grocery. It was damaged in the bombing of the Arch, and the Couple who ran it had had enough by then, so they decided to close down and move out of London.

One had to be licensed by the Ministry of Food to sell Foodstuff during the War, and the local Food-Office asked Dad if he was interested in taking over the License, as his was the nearest Food Shop.

Dad was only too pleased to take it, as he was having a thin time of it with the Rationing.

He bought all the Scales and Equipment, so he was now also a Greengrocer, selling fresh Fruit and Vegetables, as well as some Grocery, Eggs and Butter.

This meant an early morning visit to Market for fresh produce every day.

Dad had a friend with a Greengrocery Business a little way away who had a Horse and Cart.

He would pick Dad up very early in the mornings, on his way to the Borough Market, near London Bridge, and drop our stuff off on the way back.

His name was Bill Wood, and he rented a Stable a few streets away from us, with a little Yard for the Cart.

I was home for the Summer Holidays, and of course I wanted to go to Market with them, and help in the Shop to earn some pocket-money.

I enjoyed my trips to the Market, and didn't mind getting up in the small hours. London was so quiet, with hardly any traffic before the Buses started running.

Bill's Horse was a Welsh Cob, Strawberry Roan in colour, named "Girl" or "Gell" as pronounced by Bill, who was a real Cockney of the old order, always immaculate in his tweed suit with Poacher's pockets in the jacket, cap, silk scarf or "choker", and brown boots.

Gell was a very intelligent animal with a mind of her own. Most mornings she was in a hurry to get to Market so that she could get her Nose-bag on, and would get a bit impatient at road-junctions if we had to wait. She knew all the horse-troughs on our route, and would snort and toss her head when we came to a corner near one if she was thirsty. Bill knew the signs and always let her have a drink.

Bill showed me how to hold the reins between my fingers and guide the Horse with one hand, and soon I was able to drive the Cart, under supervision of course.

I would meet Bill at the stable every morning and learned to groom the Horse, harness her up, and hitch her to the Cart, actually with a lot of help from "Gell", who knew exactly what to do, and would hold her head down while I slipped the collar upside-down over her head, then turned it the right way-up on her neck.

She would even back on to the shafts without being told while I held them up, pushed the ends through the slings and fixed the Traces. Soon, I was doing it on my own while Bill "mucked" the stable out and spread fresh wood-chips for the next night's bed.

Bill had trained Gell very well, he had a way with Horses as he was an old Cavalryman.

He never used the whip on her, but would let her know he had it by flicking it gently along her flank if she got the sulks.

I learned a lot about horses from him. He showed me how to look out for ailments and said "Always look after your horse and she'll look after you". When he showed me how to do something and he caught me trying a shortcut, he would say "There's only one way to do a thing Ken, and that's the right way!" I've always remembered that, and it's stood me in good stead.

I suppose it's not generally known, but Horse-food was actually on the ration during the war, at least oats and grains were. Hay-chaff was plentiful, but not much good for a working horse. We used to go to the Corn-chandlers every so often for Gell's

allowance of clover-chaff and oats, which was ample anyway. Every month, Bill was also allowed a bale of Clover, which had a lovely smell and was a treat for Gell. I don't know why, but horse-food was always referred to by the old cockneys as "bait".

Our way to the Borough Market took us across Tower Bridge Road, along Druid Street past the burnt-out roofless shell of St John's Church on the corner, it's slender white Spire with Weather-Vane still intact after being fire-bombed.

The first time I saw the gutted Church, surrounded by wreaths of mist at daybreak, I thought it was still smouldering. It was a very sad sight. The smell of damp, burnt timber that hit the nostrils as we passed was unforgettable.

Our route then led us into Crucifix Lane and St Thomas Street past the bricked-up Arches of the roads underneath London-Bridge Station that lead to Tooley Street.

These Arches were used as Air-Raid Shelters by the Residents of the many Tenement Buildings nearby. They thought they were safe, and used to sleep in them, but around 300 people died when the Stainer Street Arch received a direct hit through the Station at the height of the Blitz.

Later in the War, many more people sheltering in the Joiner Street Arch opposite Guy's Hospital suffered the same fate

It was a bit creepy, and I felt a bit uneasy going past these places in the small hours at first, but gradually got hardened to it and became fatalistic like Dad and Bill.

The "stand" for our Cart was right at the top of St Thomas Street between Guy's Hospital and the Borough High Street junction.

The trader's vehicles were tended by a Cart-Minder, who would direct the Market-Porters to the right vehicle when they brought the goods out on their barrows.

Our Cart-Minder was called "Sailor". He was a quiet old chap. You couldn't see much of him as he wore a stiff-peaked Cap over his forehead, and his face was covered in whiskers and a walrus moustache. He always wore a black oilskin coat down to his ankles, and rubber Wellington boots, perhaps that's why he was called "Sailor".

The Borough Market was a fascinating place to be at in the early morning before dawn. Because of the Blackout, the open-fronted Shops only had a small lamp at the back above the Salesman's desk.

My faourite place was the open Square behind the "Globe" Public-House, backing on to Southwark Cathedral. Here the Growers from the Farms in Kent and Essex had their Pitches, and did business by the light of Oil-Lamps.

There was always a lovely aroma of Apples, Plums and other Fruit round there.

I can still imagine the delicious scent of fresh-picked Worcester-Pearmains and Cox's Pippins even now.

The Growers didn't mind us sampling the wares, and I had many a good feed of fruit before Breakfast.

There was a Cafe in the other open Square known as the "Jubilee" behind the covered Market. Dad and Bill took me there for a snack when they'd done their business. The tea was always good, and the Sausage Sandwiches with Brown Sauce were out of this World.

Then I'd go back and wait on the Cart for the Porters to bring the goods out, and help load it up.

London Bridge and St Thomas Street was a very busy place first thing in the morning.

Swarms of People made their way down Borough High Street from the Railway Station, and many passed us in St Thomas Street on their way to Guy's Hospital.

I'd see a lot of the same faces every morning.

Guy's had already suffered a bit of bomb damage, but was still up and running, as it remained throughout the War.

In 1943, I had occasion to visit a friend who was injured in a road accident and taken in there.

The Wards were shored up with massive timber scaffolding to protect the Patients from roof collapse if there was a hit by a bomb.

I marvelled at this, one never stopped to think of the fact that bed-ridden Patients couldn't go to the Air-Raid Shelter, and there were hundreds of Patients in Guy's Hospital.

By the time the School Holidays came to an end, I was an old hand at looking after the Horse and helping in the Shop.

Luckily for me, Colfe's Grammar School at Lewisham had opened as the South-East London Emergency Grammar School for Boys who were not evacuated, and I was able to prevail upon my Parents to let me stay at home and go there.

I never saw Aunt Flo and her family at Torquay again, but George came round to see me a few times when he was home for the holidays, so I got all the news.

I enjoyed my couple of years at Colfe's, although it was a long Bus journey to Lewisham every morning, and I was usually late, because the Bus service was unreliable with hold-ups for one reason or another.

Because of the fuel shortage, some Buses towed a little trailer behind them carrying a gas-tank, and one of the strangest sights to be seen on the road was the Doctor's Car with a rectangular fabric gas-bag on the roof-rack billowing in the wind.

Things were a bit more free and easy at Colfe's than they'd been at St Olave's, and as we all came from different Schools, Uniforms didn't matter so much.

Some of us who came from a long way off, and needed School-Dinners, used to make our own way to the Convent at the top of Belmont Hill near Blackheath Village where our meal was waiting for us.

On the way up the hill, on the right-hand side of the road, there was a shoulder-height brick wall enclosing some open ground, and you could see over it across the rooftops below to Deptford and Bermondsey beyond.

One bright sunny day in 1942, while walking up Belmont Hill on our way to the Convent, my friends and I heard the sound of Aircraft engines and loud explosions. There hadn't been any Air-Raid Warning, but as we peered over the wall, we actually looked down on two German Planes swooping low and dropping bombs.

It was all so clear in the bright sunlight, like something out of a colour movie.

I could plainly see the khaki, green and yellow camouflage, the black crosses, swastikas, and numbers on the Planes.

I even saw the heads of the two crew-men in the nearest one as it turned after it's dive, with the sunlight flashing on the cockpit glass. Then the bombs exploded and smoke rose from below.

Just then, a shadow fell across us, and we heard loud engine noise as another Plane dived from behind us towards the lower ground, it's Machine-Guns chattering.

We crouched down close to the wall, hearing splinters flying, and as soon as he'd passed over, ran hell for leather up to the Convent.

This must have been the Plane that callously bombed and machine-gunned the School at Catford, close by Lewisham, where children were playing in the Playground at Lunch-time, and many were killed and injured.

I heard afterwards that Jerry had made a hit-and-run attack with Fighter-Bombers. Flying low under our Radar-screen, they caught our defences napping.

This was why there'd been no Air-Raid Warning, and the Barrage-Balloons hadn't gone up.

One of the bombs we saw being dropped landed quite near home. On a road-junction near Surrey Docks, known as the "Red Lion", after the name of a Pub on the corner.

It demolished the Midland Bank, killing the Manager as well as injuring Staff and Customers.

Also killed was the Policeman on Point-Duty at the Junction. He must have been blown to pieces, as only scraps of Uniform were found.

He was a Special Constable, a friendly man, and a familiar figure in the district.

He had a large Hook-Nose, which often had a dew-drop on the end in the Winter. Some people referred to him as "Hooky," and others as "Dew-Drop."

It was very sad that he went like that. If the Warning had sounded, he'd have taken cover.

To be Continued.

Contributed originally by dwakefield (BBC WW2 People's War)

From WW2 I have hundreds of memories. In many cases the adults were distressed but growing up with war, many children accepted much of it as normal. People’s experiences depend so much upon where they were.

Born in February 1936 I have just a few pre-war memories from 1939. One is of a sunny lunchtime in our Walthamstow (London E.17) house, another is of our Anderson air-raid shelter being constructed at the end of the garden (most winters it needed baling as it would get several inches of water in it, being deeper than the adjacent sportsfield ditch).

A great trench was dug by steam shovel across the middle of that neighbouring sports field (and through our local Epping Forest) as defence works. Concrete blocks about a metre cube were prepared where the trenches met the main roads, ready to be moved into position and block the road if we were attacked. For the next 10 years us kids loved to play on/around the blocks and the spoil heaps lining the muddy trenches.

In 1940 my father’s employer moved from Smithfield to Brasted near Sevenoaks (Kent) where I started school. With the call-up of most male teachers, my huge class was for 4~7 and the other class was for 8~11.

While there, I knew of the rationing, so one day while my mother was shopping I picked, then boiled buttercups on the kitchen range hoping to make butter.

My mother went to First Aid classes and I was used as a child subject for bandaging. One spring day we walked up our lane to the top of Toy’s Hill to see the remains of a German plane shot down the previous night.

Our cottage was on a hillside so when the warehouses near to Tower Bridge were badly blitzed one night, we all stood in the garden to see the big red flickering glow.

Quite a few times in 1940 we travelled back to Walthamstow and I particularly remember several times walking from London Bridge station to Liverpool Street station after a previous night’s bombing. On one occasion we were allowed to walk along Gracechurch St. while the buildings on the other side of the street were on fire and the firemen using their hoses. Other times we had longer diversions to avoid fires or buildings in a dangerous state (some remained propped up till the 1950’s).

Platforms carrying pumps were built around the piers of some bridges so as to pump Thames-water into the city via cast iron mains in the gutter or on the pavement (or both). Where the mains were in parallel and pedestrians needed to cross them there were wooden boards across. Branching off the mains were lots of hoses.

When dad had been called-up, mum and I returned to our Walthamstow house There were about 45~50 in my class and my school held about 600 on three floors but the air-raid shelters weren’t ready. If the air-raid sirens went during school hours we would all squeeze into the cloakrooms and onto the staircases to avoid any flying glass from a blast as there were only tiny slit windows there.

My teacher’s mother had gone to the window in the middle of the night to look at the searchlights, but died from lacerations when a bomb fell nearby.

Many buses had blast netting on their windows and some had blackout curtains.

Some double-decker buses had a bag on top containing gas as fuel instead of petrol and others pulled a little trailer for their gas.

When paper became short at school, many of us took our 4 page (1 sheet) newspaper to school and wrote our sums and spelling tests in the margins. The papers were then gathered up and some went to the local fish shop for him to wrap his customers fish in, while the rest was torn into squares and issued by teacher from a cupboard if you needed to use the toilet.

Quite often while in the playground we saw fighter aircraft in dogfights at altitude weaving condensation trails. The alert seemed to go only if there was a risk of bombs.

By 1944 we often saw squadrons of 27 allied bombers heading for Europe. Sometimes 5, 10 or even 20+ squadrons would fly eastwards in succession presumably navigating by the white concrete of our local North Circular Road (A406) and then the Southend Road and the railway to Harwich much as the airliners heading for Heathrow still do (in reverse) in 2003.

(Not built with tarmac as concrete gave employment in the early 1930’s depression.)

There were about 6 phones in our street of 56 houses. One day in 1940 a neighbour came to say my dad had phoned her that he was moving camp and would be at Kings Cross station till 2 pm. Mum got us there in time and found the special train loading about a thousand men. She asked a corporal at the gate and the word was rapidly passed up the platform that AC2 Wakefield’s wife was at the gate and he was allowed to come and speak to us.

In early 1941 we got away from the bombing for a week to see dad in training at Bridlington. I remember Flamborough Head and the passing convoys of colliers and steamers hugging the coast.

In January 1942 the bombing got mum down again so we went for a break to Helston (Cornwall) and took the bus which was full of airmen to Mullion. Mum got plenty of attention as the only woman and I was passed from father to father to briefly sit on their knees as they were missing their own children. Mullion Cove and the Lizard Point featured in many of my school compositions thereafter.

A similar scare later in 1942 took us to Bath unannounced. While mum went to contact dad that we had come and to find overnight accommodation, she told a porter what was happening and left me for a couple of hours with our suitcase (and a luggage label on me) by the water crane on the platform where the London to Bristol trains would stop to refill. Most of the engine crews spoke to me. You wouldn’t leave a 6 year old like that now !

One winters night in 1942 the bombing was worse so mum and I went to the communal shelter at the end of our street. Only families without husbands were there. One lady realised that she had slammed her front door without her keys being in her handbag so, during a lull in the bombing at about 4 am, I ( as the oldest male) and the ladies 2 daughters (all of us under 10) were sent to see whether their back door was unlocked. It wasn’t, but a fanlight was open so the girls pushed me through to get the keys off the sideboard and bring them out via the front door.

As our Anderson shelter was so often wet we mostly sheltered in the small cupboard under our stairs. We could just squeeze in 4. (1930’s houses used substantial timber.)

On rare occasions with daylight raids, passers-by would shelter with us, e.g. our milkman, leaving his handcart outside (he had a struggle to push it up the local hill).

If we went by tube in the evening, then in some central London tube stations you would have perhaps only 3 feet of platform edge to walk on, the rest being occupied by scores of families in sleeping bags or blankets on the platform. Sometimes you had to step over a persons legs or belongings. Some stations had bunks 2 high lining the wall. It was very good-natured. Pushing would have been so dangerous !

If we were caught out in an air raid in the evening I would be fascinated by the searchlights scanning the sky as we walked through the blacked out streets. Even the cars had their headlights covered with only a 4x2 cm slit (and a 1.5 cm shield above).

Sometimes the searchlights would latch onto a German aircraft, then the guns in our neighbouring sports field would fire. One day I had to hand in my collection of shrapnel (supposedly to help the war effort by recycling, but perhaps because of my blisters from the phosphorous on the tracer bullet remnants).

Tilers were often needed in our street because so much shrapnel was falling, breaking the rooftiles and then the rain would get in and damage ceilings, etc..

Around town, bomb damage was common. Perhaps 2 houses in a terrace gone but bits of a bedroom hanging there on an adjoining wall. In one case an upright piano up there on a small piece of bedroom floor. Blast would blow out shop windows so they would be boarded up and they continued to trade, often by a single lamp bulb

Our nearest bomb obliterated the tennis court at the end of the street, so it was turned into an allotment garden. We dug up part of our garden so as to grow vegetables. Our fox terrier had to be put down in 1940 because there was insufficient food and he was upset by the noise of guns and bombs.

Letters from dad meant so much, especially with his sketches of his colleagues. Sometimes he sent a biscuit tin of blackberries, etc. picked from around his camp.

By 1944 convoys of troops and equipment mostly eastbound along our narrow North Circular Road passed almost hourly and some took a rest on the ground allocated for the second carriageway. Local ladies would offer up tea etc. to the lads. I remember seeing a convoy of tanks move off while the lads were pouring their tea, they handed the teapot to another lady up the road who brought it back to it’s owner. With rationing, I don’t know where they got so much tea from. There was so much goodwill, especially to those who were travelling.

The doodlebugs started in 1944, often coming without the air-raid siren sounding. Their chug-chug was alarming but while they chugged they were not falling. The terror was if their motor stopped before they had passed over you, then you waited what seemed ages for the bang. Again, the adults were more worried than us kids.

I only heard two V2’s. Falling from up to 70 miles above they were supersonic, so first you heard the bang and then you heard the approaching scream getting fainter, then you knew that you had survived ! Out one day, one fell a quarter mile away.

Late 1944 we moved to Bretforton in the Vale of Evesham (Worcestershire) and then Badsey village bakery before moving into the servants half of a 14th century manor house that hadn’t been occupied since it held German prisoners of war in 1919. The dark solitary confinement cell was upstairs with the regulations in german. The kitchen was stone flagged and some 40 x 15 feet while the door key was iron and weighed almost a kilo. It was unheated so we lived in the buttery (lined with copper to keep out the mice we were told). Sanitation was a bucket.

3 feet outside the back door was a wooden cover over a 4 foot diameter well.

The farmer in the main house once moved his large table to show dad’s colleagues a large slab that tilted and a tunnel below that went out under the orchard.

The villagers still talked about the one bomb that had fallen in fields 3 miles away a couple of years earlier.

The day we moved there, while my mother looked after my newly born handicapped sister, I was sent 3 miles to the butcher in the next village (past an airfield) with our ration books to sign on with him and bring back some meat to cook. Would you ask an 8 year old these days.

One day in 1944 while walking home from school, I met an American sergeant, the first negro that I had seen. He shared his packet of chips with me while showing me some pictures of his own wife and kids back home in the USA.

At Xmas 1944 many local children were taken by Air Force lorries to a party in Evesham Town Hall where we were given toys (mostly of wood and painted with aircraft dope) made by the servicemen at various local camps.

After D-day I learnt my geography of Europe by putting a map out of the Daily Mail onto the wall and inserting pins joined by wool to show the state of advance as it was reported on the radio. Pathe-News at the cinema supplemented newspaper reports.

I helped pick fruit in a market garden in 1945 and went with the horse and cart to the local single siding alongside the London to Worcester line and helped load the wagon.

On VE-day everybody celebrated, especially the Canadian airmen (who had a giant bonfire of unwanted aircraft bits).

By VJ-day we were back in London. I had attended 7 schools between 1940 and 1945.

Most classes I had been in had over 40 pupils (two had 70+ with the walls folded back) and some classes spanned several years. One school had a lady teacher for the beginners and a man for a huge class of up to school leaving age.

Teachers were mostly women and with the class sizes, were friendly but strict and were backed by parents. A slap, hands on head, stand outside, lines, ruler or cane depending upon the offence. Once I couldn’t hold a spoon at table for 2 days.

Teachers often selected the abler pupils to assist those finding a subject difficult. I was o.k. at reading and arithmetic but useless at crop rotation and recognising plants, i.e. what was taught to 8 year olds varied around the country.

In 1946 my father was demobbed. He found a way into the Mall for us for the Victory Parade. The crowd was thick, but as usual us children were passed to the front (some over peoples heads) and sat in front of the policemen. Afterwards the crowd helped us to rejoin our parents. It was a memorable view of the service contingents and those on the Reviewing Stand including King George VI, Winston Churchill and General Montgomery.

So, as I started out by saying, for a child it was a fascinating time if sometimes scary, but for the adults there was so much worry, fear, suffering and loss of possessions and loved ones. An uncle’s ammunition convoy blew to bits.

Contributed originally by Johnosborne (BBC WW2 People's War)

My personal recollections, 64 years on, of my involvement

As a civilian, in the evacuation from Dunkirk

At the end of May, 1940

by

John Osborne

May 2004

My name is John Osborne I live in Cheadle Hulme, just south of Manchester and as this is written I am 86 years old.

One of my grandsons asked me, as part of a school project, to record my recollections, 64 years on, of my involvement, as a civilian, in the evacuation from Dunkirk at the end of May, 1940. After such a long passage of time since the actual event, my recollections are now, inevitably, embellished by what I have read over the years and also, probably, by a few imaginative inventions of my own. These, nevertheless, are my recollections as of today.

I was born in 1918 at North Cray, Kent, near to Sidcup where I lived until 1957, when my work took me to the Manchester area.

On leaving school in 1934 I went to work with John Knight Ltd the then famous soap manufacturers with such brands as Family health and Knights Castille toilet soaps, Royal Primrose and Hustler washing soaps and Shavallo shaving products. This company has long since been absorbed into the Unilever Empire. John Knight’s works and offices, the Royal Primrose Soap Works were in East London at Silvertown, E16 which is on the North bank of the Thames, roughly opposite to Blackheath, between Woolwich, the site of the Royal Military Academy, and Greenwich with the Royal Naval College.

To get to work at Silvertown from Sidcup I had to cross the Thames, either under or over. In those days there was a pedestrian tunnel under the river at Woolwich and a road route thro8ugh the Blackwall tunnel. However I often used the Woolwich Free Ferry, which transported pedestrians and vehicles over to North Woolwich in a few minutes. Whenever I made this short journey across the river I was always interested to watch all sorts of craft plying to and fro. I particularly remember the sun class of tugs, which were always busy on that stretch of the tideway.

In the years before the war I, with my cousins and some of our friends, usually spent our summer holidays sailing and boating so we all gained a basic experience of simple seamanship and boat handling.

I well remember Sunday 3rd September 1939, the day war was officially declared. We were all in church listening, on my portable radio, to the Prime Minister, Neville chamberlain making his statement to the nation. There was a large congregation and, as soon as the Prime Minister finished speaking, our minister closed the service and we set off to walk home. On the way the air-raid sirens sounded off for the first time and everyone expected bombs to start raining down!

It was of course a false alarm but a good foretaste of what was to follow in the times ahead. But that again is another story.

The next day, Monday 4th September, a friend and I drove to Chatham on his motorbike, a 350cc Rudge, to offer our services as volunteers in the Royal Navy. We were surprised, and a little disappointed, to find that the only volunteers who were being accepted immediately would be enlisted as cooks. That was not our idea of fighting a war although we were both to discover, in very different active service circumstances, to what extent cooks and stewards could improve or mar life afloat. So we returned home to await our ‘call-up’ papers which we did not think would be long delayed.

I was then told that those in possession of a Yacht Master’s (Coastal) Certificate would be considered for direct entry into the Royal Navy as R.N.V.R. Officers — Sub-Lieutenants or Midshipmen, according to age. Early in 1940, therefore I commenced studying for this Board of Trade Certificate at Captain O. M. Watts’ Navigation School in Albermarle Street, London W.1.

Most of those studying with me had sailing boat experience and were hoping to enter the Royal Navy soon as R.N.V.R. Officers. We were therefore not surprised to be told, when we arrived for lectures on Thursday 30th May 1940, that the Admiralty wanted to see us all and that we were to report to the Port of London Authority Building near the Tower of London at 18.30 that evening. It did not occur to us that it was rather strange to have to report to the P.L.A. Building and not to the Admiralty, but after all there was a war on.

Our lectures were suspended and, as I was expecting to be interviewed with a view to being granted an R.N.V.R. Commission in the Royal Navy, I went home, smartened myself up, put on my best suit and collected together my latest school reports, examination certificates and references.

When we reported to the P.L.A. Building later in the day, as instructed, there was no evidence of selection interviews being conducted. Instead a large crowd of us was ushered into a hall and told to ‘pay attention!’ An announcement was being made by a Naval Officer that a secret and probably dangerous operation was being mounted which called for the short-term services of anyone, of any age, with some basic knowledge of small boats and their handling. It was not possible at that stage for any more details to be given, we were told, but anyone who did not wish to participate was free to withdraw. I do not recall that anyone did so. We were, however, permitted to contact our families to tell, them that we might be away for a few days ‘on a dangerous mission’.

Of course, as soon as the news of the evacuation from Dunkirk was made public everyone knew that we were to be involved in some capacity or other. We told in general terms that a large fleet of small boats was being assembled to go across the Channel to lift soldiers from the beeches to the east of Dunkirk harbour.

We were then taken by coach to Tilbury, all still civilians in our ‘interview’ suits.

We arrived at Tilbury later that day, were ‘signed on’ as Merchant Service Deck-hands and issued with regulation steel helmets. I still have my ‘tin hat’ as a memento. We still, however, did not know what our role in the operation was to be.

I was in a party who were then taken to the quayside where, alongside, were several ships’ lifeboats of the traditional type carried by all ocean going passenger liners pre-war, each at least 30 feet long. We were detailed to man these lifeboats in crews of about seven hands in each.

(A hand is a seagoing term from the days of sail for a sailor who was reckoned to use one hand for himself and one to do his work.)

The lifeboats with their crews aboard were then formed into trots (lines of small boats secured one behind the other ready for towing) of four or five boats and taken in tow by a tug. Ours was a Sun tug IV, which I used to see from the Woolwich ferry on my way to work. The tug towed tow trots alongside each other so the helmsmen had to steer in order to keep clear of the boats alongside and avoid collision when under way.

By this time it was quite late in the evening and dark when we set off, so we were told, for Southend pier to take on board provisions. We arrived there, without incident, at around 01.30 Friday morning and were issued with basic provisions of bread and tinned meat. We then set off for Ramsgate where we received our final orders and set sail again, this time for a midnight rendezvous off the Dunkirk beaches. During the crossing the tug crew regularly sent buckets, literally, of tea down the line to the boats in tow. We were the end boat in our line so by the time the bucket reached us them little tea that was left was cold and diluted with sea water!

The precise timetable of events over the next 24 hours is, after all these years, no longer totally reliable but the events described all happened.

Our route to Dunkirk was by no means direct as had to keep to swept channels free of mines. In any case there were so many craft of all shapes and sizes making for the same destination that we needed only to follow the fleet. My vivid and lasting impression of this stage of the operation is of a calm, flat, sea covered with an armada of assorted ships and boats. This is well described by Norman Gelb in his book “Dunkirk — The Incredible escape” which was published in 1990 and is based on detailed research of allied and German records.

He writes and I quote:

“An extraordinary explosion of activity was taking place on the beaches as well. A vast flotilla of small ships and boats, far more than had been there before, appeared off the coast. The methodical work of the Admiralty’s Small Vessels Pool and the requisitioning teams Ramsey (Vice admiral R.N.) had sent out was proving its worth. It was an extraordinary sight. All manner of small and medium craft appeared — barges, train ferries, car ferries, passenger ferries, RAF launches, fishing smacks, tugs, motor powered lifeboats, oar propelled lifeboats, wherries, eel-boats, picket boats, seaplane tenders. There were yachts and pleasure vessels of all kinds, some very expensive craft, some modest DIY conversions of ship’s lifeboats. There were Thames River excursion launches with rows of slatted seats and even a Thames river fire float.

They cane from Portsmouth, Newhaven, Sheerness, Tilbury, Gravesend, Ramsgate, from all along England’s Southern and South-Eastern coasts, from ports big and small, from shipping towns and yachting harbours.

Some, from up river, had never been in the open sea before. They were manned by volunteers; men who, without being given the details, had been told that they and their vessels were urgently needed to bring soldiers home from France. Most were experienced sailors — professional or otherwise — but many were fledglings who knew nothing about maritime hazards. Had the weather been bad, some would not have risked going; neither their experience nor their craft would have been up to it. Some mariners would fore ever be convinced that the extraordinary, uncharacteristic, calm which ruled the sea during most of the ten days of Dunkirk permitting the evacuation to proceed — ‘the water was like a mill pond’ — was literally sent because ‘God had work for the British nation to do’.”

At some time after dark we arrived off the beaches at East of Dunkirk. Only small vessels, with relatively shallow draught could approach nearer than 12 miles from the shore. Our tug was able to get quite close before we were cast off and left to our own devices to row to the beach and pick up some soldiers who were patiently waiting in their thousands, continually under bomb and shell fire. Six of the crew rowed, an oar each, and one steered.

The troops were very well disciplined, just waiting in long columns, hoping to be taken off. They were all dead beat, having had a terrible time fighting their way to the beaches. We were able to get right to the sandy beach and took on board about 30 British soldiers. They were travelling ‘light’ having discarded most of their equipment. We rowed away from the shore and took our ‘passengers’ to the nearest craft lying off shore that we could find, a tug, a drifter, a trawler, anything that could risk coming in so close.

We returned to the beach; probably a different section because as soon as we approached a crowd of French soldiers, with all their equipment, rushed out into the water and climbed on board before we had a chance to turn the boat around headed out to sea. As the tide was falling we became stuck on the sand. With great difficulty we persuaded the Frenchman to get out of the boat and we were then able to turn it round and prevent it broaching (getting broadside onto the sea). At one time I was almost up to my neck in the water holding the bow of the boat pointed pout to seawards — still in my ‘interview’ suit! We transferred that load eventually to one of the waiting craft and made one or two more trips before deciding dawn was approaching and it was our turn to make the return journey and get on the way before daylight.

Through all this time we were so occupied with what we were doping that we were hardly aware of all the other activity going on all around us. It is always like this ‘in action’. There were aircraft overhead, friend and foe, all the time; continual bombardment of the town, harbour and of the beaches by the Germans. Ships were being sunk and survivors rescued. All around the town and harbour of Dunkirk fires were blazing, a heavy pall of smoke hanging over it all. From much further off shore the British ships were bombarding the German positions.

We eventually left the beaches just before dawn on Saturday, 1st June. I spent most of the return journey in the engine room of our craft trying to get warm and dry. When we reached England again we had to lie off shore before being taken to Ramsgate by tenders. Everything was very well organised and, seemingly, under control. Administrative formalities were completed and we were ‘signed off’.

I received £5 as compensation for the damage to my suit. I managed, somehow, to get a lift back to Tower Bridge pier in a launch and, having unsuccessfully tried to sell my story to the Daily Express, I eventually arrived back home in Sidcup ay around 05.30 on Sunday morning with the help of a lift on a newspaper van.

A further quote from Norman Gelb:

‘At 14.23 that afternoon (Wednesday, 5th June) the Admiralty in London officially announced ‘Operation Dynamo now completed’. The official War office communiqué said that The outstanding success of this operation, which must rank as one of the most difficult operations of war ever undertaken, ahs been due to the magnificent fighting qualities of the Allied troop; their calmness and discipline in the worst conditions; to the devotion of the Allied navies; and to the gallantry of the RAF. Although our losses have been considerable, they are small in comparison with those which a few days ago seemed inevitable’. On the last day of Dynamo 26,175 troops, almost all French, had been ferried to England from Dunkirk. The final total evacuated, including those lifted off in the days just before Operation Dynamo was launched, was 364,628, including 224,868 British. Within days many of the French troops would return to France to try, in vain, to help stem the total conquest of their nation by Hitler’s armies. But to the immense relief of Churchill, the high command in London, and the people of Britain the British army, so nearly lost, was home.’

It was reported that 887 craft took part in the evacuation which certainly was something of a miracle.

As a postscript may I add that, by the time I had successfully gained my Yachtmasters’ (Coastal) certificate, the regulations had been changed and I was required, after all, to serve as an Ordinary seaman RN before being considered for a commission. After basic training as an Ordinary seaman, I was drafted to a cruiser, HMS Southampton (a sister ship to HMS Belfast which is now berthed on the Thames near Tower Bridge). We went to the Mediterranean where we were in action with the Italian fleet, then made an interesting journey through the Suez Canal to east Africa and back to the Mediterranean to support relief convoys to Malta. There we were sunk as a result of German Stuka dive bombing on 11th January 1941.

I survived and took a passage back to the UK in a Dutch trooper MV Christaan Huytgens. Eventually I was commissioned as a Ty. Sub. Lieut. RNVR in august 1941 and was appointed to HMS Loosestrife, a Flower Class Corvette as Anti-submarine Control officer. I was promoted to Lieut. on 1st January 1943 and appointed to HMS Trent, a River Class Frigate In both ships we carried out convoy escort duty duties the North Atlantic and , in HMS Trent, in the Indian Ocean, operating between Aden, Bombay and Columbo. We also formed part of the escort of the invasion convoy to Sicily in July 1943. I was demobilised and returned to civilian employment in March 1946, having received £101.10s as war Gratuity and Post War Credit of Wages!

I can think of no better finale to this record than to offer you the treat of listening to a supreme exponent of the English language, the great war-time Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, who kept so many of us carrying on hopefully at home and overseas during the early dark days of the war, through the statements he made to the House of Commons on June 4th and June 18th, 1940.

Typed May 2004 from original recording transcript in March 1994.

Contributed originally by Rose_Edgar (BBC WW2 People's War)

I am writing this in answer to your request for memories of World War Two. I was a civil servant, 18 years old, living in South East London. The day we declared war on Germany was a warm, sunny day in September. My family and all the neighbours were gathered in our garden to await the Prime Minister’s announcement at 11a.m. We all had our wirelesses turned on and our windows open. As the chimes of Big Ben rang out, we all fell silent. Mr. Chamberlains voice was heard, with his declaration of war.

For a few moments, nobody spoke, then, everybody started talking at once. We younger ones were full of determination to join the forces, and go and sort them out. I felt at once excited and apprehensive, but determined to ‘do my bit’. I was not, however, allowed to join the forces because I worked for the government already, much to my disappointment. Our parents were very troubled; they had lived through one war, and they did not relish another. My father had fought all through that one and lost an eye.

I would like to make a point here; the scene I have just described was typical of the working class of that time, and held good through the war. People were there for each other, ready to give support and sympathy.

The government had already made Anderson shelters available for those who wanted them. We did not have one, but my Dad dug out and erected one for the next-door neighbours. I spent about two hours in it during an air raid, but decided it “wasn’t for me”. They saved many lives. They consisted of two curved sheets of corrugated iron, bolted together, lowered into a hole three or four feet deep and standing about three feet above ground level. There was a wooden bench fixed inside and you piled about two feet of earth on top. Some people planted flowers on them to hide them. At night people put a blanket over the doorway and used candles for lighting.

We were issued with gas masks, identity cards and ration books. At the office they gave us tin helmets. They also gave us a demonstration of how to use your gas mask. About fifty people were in the room together. They released tear gas and we had to hold our breath and put on our mask quickly. (When you breathed out it made a noise like a raspberry. Can you imagine fifty people all breathing out at once! Hilarious!) What was not so funny was being made to take the gas masks off before we left the room. We staggered out, eyes streaming, coughing and spluttering. This was supposed to impose on us the rule that everyone should carry their gas mask at al times! I am ashamed to say that I didn’t and neither did many others. Fortunately for us, we never had occasion to use them.

We had to cover our windows with thick material, so that no light escaped. If any light showed at all, the air raid warden would shout “put that light out”. It was said that a bomber pilot could see you strike a match from about 1000 feet. With no street lighting, walking at night was hazardous. Even places you knew well seemed unfamiliar. You found yourself bumping into things, and tripping over pavements, on nights when there was no moon. The government stuck posters everywhere exhorting you to “eat more carrots because they help you to see in the dark!” Railway stations were very dimly lit and the manes were removed, so if you were going somewhere for the first time, you had to keep asking “are we there yet?” Signposts were removed too, so it was difficult finding your way about. It might have confused an invading army but it confused us too.

Rationing began soon after the onset of war. First one or two items, then eventually most basic foods were rationed. Bread, flour, butter, margarine, sugar, tea, eggs, bacon, meat were rationed. Also clothes were rationed and petrol and coal. We had utility dresses and furniture using minimal materials. We had to make do and mend. Even beer and spirits were in short supply and cigarettes. Our diet nevertheless was a healthy one. We thrived on it. There were plenty of vegetables, other than potatoes, which were rationed, and homegrown fruit. Most people grew some vegetables in their gardens, and parks were turned into allotments.

Railings were taken away; old saucepans and other metal goods were also collected to be turned into tanks, planes, guns and munitions. People saved potato peelings and other food scraps for pig food.

In early 1940, the war on the home front began in earnest. First were ‘nuisance raids’. These lasted about 20 minutes, and went on night and day to keep people running to and from shelters, thus interrupting work and sleep. These were followed by heavy bombing raids which went on for hours and destroyed much of big cities, killing thousands of civilians. People started going down into the tube station every night and sleeping on the platforms and quite a community grew in Chislehurst caves. For the most part, people went on getting to work and home again and going to the cinema or theatre or to dances. In the cinema, when the sirens sounded an air raid warden would flash on to the screen and those who wished would go and take shelter, but mostly people just stayed put.

At night my dad and I, and sometimes some of the others of the family would stand at the open door, watching the searchlights probing the sky: sometimes you would see a bomber5 caught in the beam. Then the “ack ack” guns would start firing at it. You could see fires springing up nearby and hear the whistle and bump of the bombs landing then the explosions. The bombers had a policy of dropping incendiary bombs to start up fires, thus lighting up their targets before dropping HE bombs. Incidentally, you didn’t venture outside, because there was as much chance of being hit by shrapnel from the guns as by bombs.

The office I worked at was just down the road from London Bridge Station, and my friend Dorothea and I volunteered for fire watching duties. We had two four-storey buildings to look after and our duty was if any incendiary bombs fell on the roofs we had to put them out quickly before the fire took hold. To do this we each had a stirrup pump and a few buckets of water. The nozzle of the pump went into the bucket; you put your foot into the stirrup and pumped away, while directing the jet onto the bomb. They were put out quite easily. We were on duty on the Saturday night in 1940 when the Luftwaffe staged it big raid on the docks. We had a first class view of this, and it looked for all the world like the Great Fire of London all over again. There were fires all around. Apart from a couple of stray incendiaries we were not touched, but a block of flats along the road were razed to the ground, resulting in many deaths and London Bridge Station was badly damaged. The firemen couldn’t do much because water mains were broken and the river was at its lowest ebb. I was very worried because my dad was fire watching in the docks, by Tower Bridge.

At nine o’clock the next morning we handed over to the Sunday shift and made our way home. Dorothea lived North of the river and I to the South so we went our separate ways. I had to walk to Bromley, which was six miles away. I got to the Old Kent Road, where there were fires burning on both sides of the road. Two firemen on duty said, “you can’t go through there!” “Who says?” I said. I was determined to get home and see if the family were all right, especially my dad. They asked where I had been and I said, “Fire watching” They laughed and said “Which one did you watch?” Very funny!

I was very relieved to get home, and see that they were all right and Dad turned up soon after me. There was no public transport that day; there were too many holes in the roads and rails. If the sirens went you were on a tram or bus, they would turn everybody off and you were supposed to go down to the shelter. A lot of us just walked the rest of the way, ducking into shelters if we heard a bomb coming down. You got used to all this, you thought of it as the ‘norm’. You got fatalistic; “ If your names on it it’ll get you” we used to say. Getting to and from work was not always easy. Lorry and van drivers would pull up at the bus stops, where everyone had congregated and offer lifts to wherever they were going. Then as many as could find room would climb on and away we’d go. My younger sister Vera and I would travel together and she had further to go than me. Plenty of drivers went our way. One day, I was walking home during an air raid and I got a lift in a small van. As we got going I asked the driver what he was carrying, he said “matches”. That made me sit up!

After about eighteen months of raids we had a period of quiet, and things settled down to something like normal. Then came another menace. The VI’s, flying bombs or as we called them “Doodlebugs”. These were short, stubby pilot less planes, which had a nose packed with explosives. Their engines were set to run for a certain length of time, which would bring them over their target then cut out causing the doodlebug to fall to earth and explode. These were powerful bombs and did a lot of damage. They would send over a dozen or more at a time. You could watch them flying towards you and you hoped they would keep going but when they stopped, it was time to dash for cover. I was working at the Admiralty by that time and working alternate night and day watches. One morning, after a night watch, I went to bed for a couple of hours sleep before lunch. I had hardly closed my eyes before Mum came and told me to get up. “They are coming over in droves” she said. Grumbling, I got up and went downstairs. IO was watching them from the door when I saw one coming straight for the house. “Duck” I shouted and we made a dive for our ‘safe’ cover, by the coal cellar. As I ran, I saw, out of the corner of my eye, a wing tip hit the chimney of the house next door. The doodlebug turned a somersault and sailed over the house into the next road. There was a terrific explosion and the ceiling came down, the windows, (including frames) vanished, some of the roof disappeared and all was chaos. We were unhurt and that was all that mattered, others weren’t so lucky. Whole families were wiped out.

We were the only people who had an electric kettle and as the gas mains had been hit, in no time at all we had a queue at the door of women with their teapots and tea ration. (What would we do without our cup of tea?) Best of all was that when Mum and I went upstairs, there in my pillow was a 2ft long shard of glass. I was so glad Mum had made me get up. The repair squad came round and patched up the house, so that we could stay in it, and within weeks it was all repaired. The furniture was a mess and so were our clothes, but at the town hall they gave us dockets to replace them.

Even worse than the doodlebugs, were the V2 rockets. They gave no warning. Suddenly, there would be a huge explosion and houses, people, cars, things would disappear in a cloud of dust and all that would be left was a pile of smoking rubble. Fortunately within a few months the RAF had destroyed their bases and that was the end of air raids. No more would we find that places we had seen only yesterday had turned, overnight, into heaps of rubble and people we knew had died or been injured.

A few months later, on May 8th, 1945, the German army capitulated Victory in Europe! There was plenty to celebrate. No more blackouts, children could come home again to their families, no more bombs. Everywhere there were street parties. People got together, using their rations and anything else they could lay their hands on, and they brought their pianos and gramophones into the street. Then they danced and sang until dusk. It was good to see the street lamps on and the lights shining from windows.

I was still working at the Admiralty. The war was not yet over. There was still the Far East to be won. That night I arrived at Charring Cross Station and it took me twenty minutes to fight my way through the crowds to Admiralty Arch. The whole of the Strand, Whitehall, Trafalgar Square, Northumberland Avenue, the Mall, everywhere was a solid mass of people, singing, hugging, and dancing. It was a wonderful atmosphere.

VJ Day was much more sedate. No Street parties, just a quiet thankfulness that it was all over at last. Also we were shocked at the way it had ended, with two Atom bombs, on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Thousands of innocent people were killed in a monstrous way. The government said it shortened the war, and saved lives but we believed that was not why they used the A-bombs. We felt uneasy and yes, guilty.

Afterwards we learned the horrors of the Nazi Concentration camps, the gas ovens, the furnaces, the inhuman experiments, and the starvation. And all because they were born Jews, Gypsies, disabled. That war should never be forgotten, it should never happen again!

It was a good few years before rationing ended; life was never the same. Many people had to adjust to life without loved ones, and had to rebuild their lives in new homes

Contributed originally by hereward (BBC WW2 People's War)

I was born just before the war, 1938, and my mother died when I was eight months old. My grandmother and grandfather then stepped in, and I lived in Bermondsey with them and other assorted members of the family. My family were lightermen and watermen and lived near the docks. They had worked for Hay's Wharf for years, my grandfather since 1912 - at the start of the war he was bosun at Hibernian wharf, west of London Bridge - and on researching the family history I have found that three branches of our family had lived in London since circa 1585, some 400 years, all watermen, and in the usual tradition, apprenticed to uncles and relatives - the Houghs, the Sholts(initially the Van den Scholtes) and Collins'. All very ordinary people, hard-working and involved in the early union organisations, my grandfather being a friend of Ben Tillet, helping to raise money for the widows and orphans of injured rivermen thru' Boxing matches and socials. They were also keen sportsmen, rowing, of course, to a very high competitive level, Doggetts Coat and Badge, and in another sport, my grandmother's brother, William Hough, was the professional Lightweight Boxing Champion of England in 1902, sadly dying at the age of 19 of cholera- one wonders how far he might have progressed had he been spared? On the day the Germans first bombed London, we were out at the seaside, Margate, having a picnic, and returned to find our house had disappeared -nothing was left and neighbours were dead. we lived for some time under the railway arches in Raymouth Road, then moved down to a cottage my grandfather had rented since 1936 in kent. my grandfather, father and uncles then lived with my aunt Rose in Sidcup, (she was the secretary of Mr Chiesmans' Homeguard detachment in Chislehurst - her husband, a cooper, reserved occupation, served with this Dad's Army unit - after war he became vault keeper of the Rum vault at the Docks and thus had Prince Charles' birthday cask of very special port under his protection, given on the birth of the Prince by the Portugese government. Approaching the date of the Prince's 21st birthday, it was decided to remove this cask from bond when it was to be taken to the Prince's residence. However, my uncle, on dipping the cask, found out that over the years most of it had been drunk by Customs officers and various other dock workers, ostensibly checking that it was still okay...he was then faced with the task of replacing it surreptitiously from sources all over London, friends and companies in the wine trade. He sat down and calculated roughly the ullage - loss of liquid thru' evaporation, and in the finish was even topping it up from petrol cans of port given to him by these associates - the cask was 250 gallons - The great day dawned, representatives of all the famous wine companies attended a celebrative broaching of the cask, my uncle using a silver spiggot and silver schooners to serve them and the Duke of Edinburgh, and the general opinion was that the port was first class!! My uncle then told me that it showed how much the Great and the Good knew about Port...) whilst working on the river and my grandmother and I lived in the kentish cottage. my father slept many nights in Chislehurst caves and the underground stations whilst still working. my uncle Tom was the Captain and pilot on the river fire float "massey shaw" and took part in the evacuation of dunkirk, where the "massey shaw" rescued some 600 odd men from the beaches. He was a trained navigator (Mr George Allagiah, of the BBC, on a report of the Massey Shaw on TV, said that none of the crew were trained navigators...) who had worked on boats up the Seine before the war, transporting cheese(his birthday and name were the same as his father's, and for many years they only paid one lot of income tax by only completing one person's details instead of two...PAYE stopped all this...) My father was then called up for the navy, but decided that perhaps the army was the better bet and joined the Royal Engineers water transport section, rising to become a WO 1. At this rank, he commanded an LCT in the Normandy landings and took some of the Canadian Commandos ashore at Juno beach. He said he was more afraid of them than the Germans- they spent a lot of time on the craft painting their faces with warpaint and sharpening knives -His craft contained Hobart "funnies" and he had some part in placing tanks with ramps on the Corseulles promenade. The landings at this beach took place an hour after most of the other landings because of the tides and the Germans were well prepared - something like 20 out of the first 24 boats to the beach were destroyed. After the initial landings he helped build the Mulberry harbour, and was in Caen after it was rased to the ground.

Following this, he moved up the coast with various craft taking food to the Dutch and Belgians finally thru' the canal system and once took the surrender of a group of SS men who preferred to be taken prisoner by the English (As he approached the town where they appeared, seeing lots of black uniforms on the canalside, he told his sergeant to run up the white flag, but before this could be done, the SS unit ran up their white flag). Before this time, my uncle in the fire service went thru' the massive fire in the docks and carried a scorch mark on his face all his life from the incredible heat of the spirit warehouse fires. The "massey shaw" did sterling work throughout this period and Tom Collins found out that he could knock down walls of warehouses by training the massively powerful hose of the Massey Shaw on them and running the jet up and down - this allowed firemen to access parts of the docks blocked to them by falling debris. Other boats used by the Fire Service at this time were the Alpha, Beta and Delta, but none were so powerful as the "Massey" - now apparently in the London Museum.

In Kent, we lived more quietly, but were still machine-gunned one day by a roaming German plane near Knoxbridge- we jumped in the ditch - and listened to the German bombers every night going overhead to London. In August 1944 a V1 landed some 50yds behind our cottage in Staplehurst and we were thus homeless for the second time before I was six...this same bomb blew all the windows out of the village church.

How we learned to read and write I do not know, as I had attended some six schools before I was eleven, and lived in seven homes. During this time my grandfather had slipped down between two barges which then came together on his ankle...his footballing days were over...he was taken to Guy's hospital during an air raid, set and plastered, and collected by some railmen whom he knew and walked up the ramp at London Bridge railway station on a mail trolley to catch the train home and early retirement. His retirement would nowadays be called "active retirement", as he became involved in the black market and it was known locally in Staplehurst that if anything had gone missing, my grandfather either knew about it, had organised it, or had it...A local farmer who helped with these misdeeds was even banned from Ashford Market. In his younger days, my grandfather had been a King's swanupper, and served for many years in this honorary position under Mr Turk of Windsor. He was an avid hater of Mr Churchill, and told me tales of how Churchill had brought the troops against the miners in Tonypandy, of how he personally had fought with the police and strike breakers in the '26 strike...advised me on how to use ballbearings against police horses in union conflicts. I was told of the King wearing makeup to visit the docks during the war, and of Edward the VIII's drunken escapades... An odd thing apart from this, was that one of our forebears was the Mayor of London during the 1830's, stood as prospective Tory MP for Maidstone afterwards, became the Lord of the Manor of Wateringbury, and has a notable memorial in the village church where he built an additional extension. I can possibly claim also to be the youngest cub scout ever, because I made such a nuisance of myself to the local pack when 5 years old that they allowed me to be the pack mascot with cap and uniform...Despite all this activity, we lost no one in our immediate family so can consider ourselves lucky...My grandfather would turn over in his grave to know that my daughter is now married to a senior German civil servant and lives in Berlin, and my son, a Cambridge-educated doctor, also works in Germany - his great-great grandson is a small German boy, learning two languages and at the moment possessing dual nationality, and on his father's side of the family although no one served in the second war, one was an officer in the Kaiser's army...

Contributed originally by Bryan Boniface (BBC WW2 People's War)

JANUARY 1941

1 WED Mum and Dad spent New Year’s Eve (as usual) at Lou and Albert’s. I, on reaching home (after paying electricity bill at Wimbledon Town Hall) Found Dad ill in bed with attack of pleurisy, Jack in bed with general debility, Mum (waiting on both) with sore throat, George visiting with strained arm! Kay arrived safe.

2 THU Early morning, very cold as well as dark. Later, walking across desolate docks, face chilled to bone with blast of wind. On Kay’s behalf, called on a cleaner’s in Morden re skirt re-pleating, change disputed. Called Home Guard Headquarters for Dad.

3 FRI Weather still excessively cold — probably 40 deg F or thereabouts. Stayed in warm in evening. Found Dad better and did an odd job or two for him. George en-route to visit Elsie and children, here, picking up train at Wimbledon at 1 am.

4 SAT Dad being unable, I sent off his Income Tax for him, whether whole or part assessment, I don’t know - £3 — 11 — 4. Half day, spent it amongst our furniture looking for necessary articles. Used rummaging tactics, flat on stomach with mirror and lamp (!) at times. Found some borrowed records which owner has been worrying me for. Had some enjoyment with playing them over.

5 SUN Very cold. Helped Mum as much as possible, and straightened up furniture. Damage to date - one picture broken. To work for 4-8 duty, meeting PO en route. Usual air raid but all clear about 11 pm.

7 TUE Snow everywhere, steady fall, attempted to clear front path but soon re-covered. To food office where there were long queues, so deferred business, visiting cleaners re Kay’s skirt. AA shells blasting overhead at loan raider as I walked through streets.

8 WED Spent the night watch with Mr Blake, PO, my own PO on leave for 9 days. There were no night raids so perused last year’s official notebook, making a fresh start for 1941. Had a few hours sleep at home then went to see film version of “Pride and Prejudice”: much enjoyed.

9 THU First thing down to the food office at Merton to notify removal and to change retailer. Then called cleaners, Martin Way, and collected Kay’s skirt, sun-ray pleated and dispatched that to Blackpool. 4 pm duty: Air raid 7.12, all planes passing over.

10 FRI The violent AA explosions finished at 2 am and the comparative quiet was eerie. Left office at 8 am in moonlight and had what seemed a speedy journey home after the slower route taken over last few months. Bought Mum some flowers in return for her kindness the day Kay returned to Blackpool.

11 SAT One of the hardest day’s on duty in my official career. Mr Blake, my PO, one time athlete, walked me around Surrey Dock and it’s environs sight seeing. The afternoon was similar, walking to Pier Head to meet launch (change of stations) and hunting for a fresh arrival (small ship). Left office footsore and weary, not regretful at losing Mr Blake for a time. The change of minute places me on reserve air raid at night, finished early.

13 MON Change of station for PO’s , renewed acquaintance with a man I haven’t seen for some years, among whom was my own PO for the week, Mr Bishop. George brightened his solitary life by visiting us, and was immediately engaged by Roy, and later, Jack in chess playing. No night raid, read my book — Jane Austin’s “Northanger Abbey”.

15 WED Wintry conditions lead to a fall of snow today, making conditions mushy underfoot. As yesterday there was much to do in the dock, principally duty taking. The evening was quiet, Mum reading, Dad relaxing; Jack and Roy playing chess, whilst I amended.

16 THU Was awoken by distant and local AA guns and found a night air raid was in progress. The “all clear” went as I got up at 6 am. Damage was to be seen at a Bermondsey church, and at shops, on way to work. Half day, beautiful afternoon, sun shining on snow. Lou at Mum’s helping. Walked Merton returned records.

17 FRI Snow everywhere still but hard and rutty underfoot and still dangerous. Getting aboard vessels at buoys in dock by boat was a risky business. A Mr Rix called and examined Dad’s radio. He is a friend of a friend of Jack’s (!) Heard from Kay and replied.

18 SAT Still cold and during the morning, more snow fell, to about 4”. Not on duty till 4 pm today. Spent the morning parcelling up bedding to be put away in the furniture storeroom somewhere. I am gradually straightening things out there. The guns were booming as I reached Surrey Dock: bombs were dropped elsewhere. There was no night raid and I was able to peruse at length the second story in my Jane Austin book, “Persuasion” and find it very engrossing

20 MON My first day on the “reserve”. To the “Harpy” and before the day was out received my first commission, relieving a “Harpy” rummage officer from Wednesday — end of week. Saw the damage to the Custom House in which one man was killed and two injured a fortnight ago. Met my fellow “reserve” and other acquaintances.

21 TUE Snow having now completely melted and a grey drizzle adding to soggy ground, walking conditions require strong shoes, thankful for my brogues. Sky gave opportunities to sneak raiders and we had three “alerts”. Sent off parcel to Kay containing Betty’s shoes and tobacco for Kay’s Dad. No raid again.

22 WED Attached to rummage crew 8/4 today. In walking to and from wharves in region of Tower Bridge, saw the extensive damage done by the fire raiders about fortnight ago. Shells of buildings stand only. Mr Rix, the wireless serviceman repaired Dad’s radio: refused payment.

23 THU A dull misty day and very muddy under foot: consequently a walk to Free Trade Wharf and back to rummage a coaster was unpleasant. However, other air raid damage was to be seen and so lent a morbid interest to the week. Quiet evening around fire side. To read.

24 FRI Less congestion on the old 245 bus route (now 127), as double deckers are now employed, actually Manchester buses loaned to L.G.OC. Half day, went to Globe theatre, Piccadilly and saw Barrie’s “Dear Brutus”, an amusing and touching play. No bed-mate, I stayed at George’s.

26 SUN 8/4 Rummage. Set off in pitch darkness for South Wimbledon Station soon after 7 am. Fortunate in picking up a bus at Nelson Hospital. Dull and thick mist on the river, one or two ships got through. Quiet evening, contrast to yesterday, wrote part letter to Kay, Budget and helped Roy with homework.

28 TUE The rainy, misty day gave “sneak” raiders opportunities for doing their nasty work and four times we had warnings. Found supervisors in office rather trying, but harmonised satisfactorily. Very quiet evening, Mum, Jack, Roy and I all reading or writing. Dad — Home Guard.

29 WED Not quite so misty and only two air raid “alerts”, one early, one late.(5.40 pm). Heard from Kay, last letter was twelve days ago, Says she has not been well (pregnancy) and disinclined to write. All well otherwise. Completed letter to her started Sunday (gv) in order to send money tomorrow.

30 THU The feature of the war activity on the home front, on misty days, is the continuous “alerts” caused by low flying German aircraft with the accompanying vibrating “crumps” of bombs and AA gun explosions. We had another such day today. Staff do not shelter now.

31 FRI A morning in the “Harpy” office, spent in preparing the Sunday duty lists for the ensuing year. Half day, went to Shannon Corner Odeon and saw a delightful film “Hired Wife” Rosalind Russell and Brian Aherne, and a nasty one (war) “Pastor Hall”

FEBRUARY 1941

1 SAT A few stray sunbeams in the early afternoon gave us a break from the grey misty weather. This observed from the “Harpy” office where I spent the time, the office PO having left for his half day. The great invasion is due to begin at the first sign of good weather — hence the interest in it. Having acquired a set of boxwood chessmen cheaply (ex previous staff sports club), spent evening repairing knights, cleaning and re — lacquering other men.

2 SUN Was awakened from deep sleep at 4 am by Mr Willoughby (neighbour No 2) knocking up Jack for his 4-6 turn firewatch. Awakened again when he returned (with frozen feet) to bed. Jack is a recent volunteer. George left at 2.30 to give first aid lecture in Croydon to women. Spent much time in spare room.

7 FRI Dad about before us all this morning having been on Home Guard duties all night. Sent off a 10 lb parcel of sheets and clothing to Kay. Hope she receives it before weekend. Again attached to London Dock officer. Spent over 30 shillings on linen etc. in Ely’s Wimbledon. Also paid electricity bill. £1/14s/6d.

9 SUN Another Sunday off duty — pleasant in itself but rather worrying with it’s financial implications. Last time Kay and the children received a billeting allowance of 11s from the government, but this time they went from a non-evacuable area. Had a pleasant walk and did a few odd jobs.

10 MON Standby on the “Harpy”. Called National Registration Office (Dorset Hall) and had my identity card altered. This should have been done when I first removed. Workmen commenced erecting brick shelter at side of house. (Concrete foundation was laid last December). George came and stayed overnight. Roy met Dad from pictures.

11 TUE Day of contrasts: thick fog in morning so that patrol launch cannot proceed much below Tower Bridge, and sunshine in the afternoon so inviting that the PO (whom I was assisting) went out onto a deck seat. and revelled in it for ½ hour. Letter from Kay, replied, enclosing 5s/5d postal order.

12 WED Very ordinary day: At “Harpy” assisted office PO with revised Sunday list for Shadwell and RC stations. In the evening, Dad went off to Home Guard Headquarters, (Grand Drive). Was deputed to 8/10 pm watch and spent rest of night there. I played chess with Roy; mended letter rack.

13 THU Sent off Sid a set of brass buttons, 9 numerals for which he had asked, and to which we had all contributed. On arrival home, found Lou had been, leaving me a suitcase of clothes she had washed for me. The complete wash-up of all dirty linen and bedding, etc. has cost me nearly 10 shillings.

15 SAT A dull day turned into a glorious bright one by 1 pm. Worked at the Sunday List (see prec.) and left for half day at noon. There was a raid on so I walked over to London Bridge Station where the underground terminate during raids due to the line running under the river when continuing northwards. Dad and I put in some Spartan work, replacing the furniture in the “furniture room”. Drawers and cupboards are more available and a much broader gangway made.

18 TUE Continued clerical work as prec. And completed second copy of list. There was an air raid after I had made entry in diary yesterday. Bombs at Garesfield and slight traffic dislocation. Dad “Home Guarding” all night. Helped Roy with homework, listened to Handel’s “Water Music”.

19 WED Upon reading in newspaper that Puccini’s opera “Madam Butterfly” was to be performed at 2.30 pm at New Theatre today, I decided to go and secured a half day, lined up at the head of the gallery queue and saw a splendid performance (to a half filled house!!). Madam Butterfly = Joan Cross. Fine view of orchestra = 28 performers.

20 THU A cold but clear day. Finished up my Sunday scheming job in office and was told my job for tomorrow would be rummage West India Docks. Saw Mr W in room 11 who said he had in mind my travelling difficulties but the job was unavoidable. Dad and I spent evening trying to mend cleaner hose — no good.

21 FRI In West India Docks today. A straight forward journey via South Wimbledon, London Bridge and Blackwall tunnel was accomplished in 1¾ hours. Total fares (workman’s ticket) 1s/9d! — far too much expense for my pocket. Met many old friends, saw part of dock damage. George came evening, Dad brought chess board home from his work — a fine job!

24 MON Had my half day very early and spent it with Fred and Mabel and children who had come on a birthday (Fred’s) visit. Doll also called in so we had a brt gathering. Keith, quite a big boy running about and talking: Pam quiet by contrast. All left at 6 pm. Dad to Home Guard.

26 WED Police dragging river this morning, it being suspected someone having fallen overboard, owing to our launch crew recovering a wallet (no money) floating on the water. “Wharves” officer reporting sick gave me a job for the day. Sent off month’s money to Kay. Quiet evening round fireside. Read evening.

27 THU Am reading the second book of A. Bennett’s works “Imperial palace”, the other one was “Riceyman’s Steps”. It is proving very engrossing. Had plenty of opportunity for making headway on the "Harpy" reserve during work, 2 “alerts”, sneak raiders owing to clouded sky. Roy returned school today — better now. Budget.