Bombs dropped in the borough of: Westminster

Description

Total number of bombs dropped from 7th October 1940 to 6th June 1941 in Westminster:

- High Explosive Bomb

- 1,436

- Parachute Mine

- 10

Number of bombs dropped during the week of 7th October 1940 to 14th of October:

Number of bombs dropped during the first 24h of the Blitz:

Memories in Westminster

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by BoyFarthing (BBC WW2 People's War)

I didn’t like to admit it, because everyone was saying how terrible it was, but all the goings on were more exciting than I’d ever imagined. Everything was changing. Some men came along and cut down all the iron railings in front of the houses in Digby Road (to make tanks they said); Boy scouts collected old aluminium saucepans (to make Spitfires); Machines came and dug huge holes in the Common right where we used to play football (to make sandbags); Everyone was given a gas mask (which I hated) that had to be carried wherever you went; An air raid shelter made from sheets of corrugated iron, was put up at the end of our garden, where the chickens used to be; Our trains were full of soldiers, waving and cheering, all going one way — towards the seaside; Silver barrage balloons floated over the rooftops; Policemen wore tin hats painted blue, with the letter P on the front; Fire engines were painted grey; At night it was pitch dark outside because of the blackout; Dad dug up most of his flower beds to plant potatoes and runner beans; And, best of all, I watched it all happening, day by day, almost on my own. That is, without all my school chums getting in the way and having to have their say. For they’d all been evacuated into the country somewhere or other, but our family were still at number 69, just as usual. For when the letters first came from our schools — the girls to go to Wales, me to Norfolk — Mum would have none of it. “Your not going anywhere” she said “We’re all staying together”. So we did. But it was never again the same as it used to be. Even though, as the weeks went by, and nothing happened, it was easy enough to forget that there was a war on at all.

Which is why, when it got to the first week of June 1940, it seemed only natural that, as usual, we went on our weeks summer holiday to Bognor Regis on the South coast, as usual. The fact that only the week before, our army had escaped from the Germans by the skin of its teeth by being ferried across the Channel from Dunkirk by almost anything that floated, was hardly remarked about. We had of course watched the endless trains rumble their way back from the direction of the seaside, silent and with the carriage blinds drawn, but that didn’t interfere with our plans. Mum and Dad had worked hard, saved hard, for their holiday and they weren’t having them upset by other people’s problems.

But for my Dad it meant a great deal more than that. During the first world war, as a young man of eighteen, he’d fought in the mud and blood of the trenches at Ypres, Passhendel and Vimy Ridge. He came back with the certain knowledge that all war is wrong. It may mean glory, fame and fortune to the handful who relish it, but for the great majority of ordinary men and their families it brings only hardship, pain and tears. His way of expressing it was to ignore it. To show the strength of his feelings by refusing to take part. Our family holiday to the very centre of the conflict, in the darkest days of our darkest hour, was one man’s public demonstration of his private beliefs

.

It started off just like any other Saturday afternoon: Dad in the garden, Mum in the kitchen, the two girls gone to the pictures, me just mucking about. Warm sunshine, clear blue skies. The air raid siren had just been sounded, but even that was normal. We’d got used to it by now. Just had to wait for the wailing and moaning to go quiet and, before you knew it, the cheerful high-pitched note of the all clear started up. But this time it didn’t. Instead, there comes the drone of aeroplane engines. Lots of them. High up. And the boom, boom, boom of anti-aircraft guns. The sound gets louder and louder until the air seems to quiver. And only then, when it seems almost overhead, can you see the tiny black dots against the deep, empty blue of the sky. Dozens and dozens of them. Neatly arranged in V shaped patterns, so high, so slow, they hardly seem to move. Then other, single dots, dropping down through them from above. The faint chatter of machine guns. A thin, black thread of smoke unravelling towards the ground. Is it one of theirs or one of ours? Clusters of tiny puffs of white, drifting along together like dandelion seeds. Then one, larger than the rest, gently parachuting towards the ground. And another. And another. Everything happening in the slowest of slow motions. Seeming to hang there in the sky, too lazy to get a move on. But still the black dots go on and on.

Dad goes off to meet the girls. Mum makes the tea. I can’t take my eyes off what’s going on. Great clouds of white and grey smoke billowing up into the sky way over beyond the school. People come out into the street to watch. The word goes round that “The poor old Docks have copped it”. By the time the sun goes down the planes have gone, the all clear sounded, and the smoke towers right across the horizon. Then as the light fades, a red fiery glow shines brighter and brighter. Even from this far away we can see it flicker and flash on the clouds above like some gigantic furnace. Everyone seems remarkably calm. As though not quite believing what they see. Then one of our neighbours, a man who always kept to himself, runs up and down the street shouting “Isleworth! Isleworth! It’s alright at Isleworth! Come on, we’ve all got to go to Isleworth! That’s where I’m going — Isleworth!” But no one takes any notice of him. And we can’t all go to Isleworth — wherever that is. Then where can we go? What can we do? And by way of an ironic answer, the siren starts it’s wailing again.

We spend that night in the shelter at the end of the garden. Listening to the crump of bombs in the distance. Thinking about the poor devils underneath it all. Among them are probably one of Dad’s close friends from work, George Nesbitt, a driver, his wife Iris, and their twelve-year-old daughter, Eileen. They live at Stepney, right by the docks. We’d once been there for tea. A block of flats with narrow stone stairs and tiny little rooms. From an iron balcony you could see over the high dock’s wall at the forest of cranes and painted funnels of the ships. Mr Nesbitt knew all about them. “ The red one with the yellow and black bands and the letter W is The West Indies Company. Came in on Wednesday with bananas, sugar, and I daresay a few crates of rum. She’s due to be loaded with flour, apples and tinned vegetables — and that one next to it…” He also knows a lot about birds. Every corner of their flat with a birdcage of chirping, flashing, brightly coloured feathers and bright, winking eyes. In the kitchen a tame parrot that coos and squawks in private conversation with Mrs Nesbitt. Eileen is a quiet girl who reads a lot and, like her mother, is quick to see the funny side of things. We’d once spent a holiday with them at Bognor. One of the best we’d ever had. Sitting here, in the chilly dankness of our shelter, it’s best not to think what might have happened to them. But difficult not to.

The next night is the same. Only worse. And the next. Ditto. We seem to have hardly slept. And it’s getting closer. More widely spread. Mum and Dad seem to take it in their stride. Unruffled by it all. Almost as though it wasn’t really happening. Anxious only to see that we’re not going cold or hungry. Then one night, after about a week of this, it suddenly landed on our doorstep.

At the end of our garden is a brick wall. On the other side, a short row of terraced houses. Then another, much higher, wall. And on the other side of that, the Berger paint factory. One of the largest in London. A place so inflammable that even the smallest fire there had always bought out the fire engines like a swarm of bees. Now the whole place is alight. Tanks exploding. Flames shooting high up in the air. Bright enough to read a newspaper if anyone was so daft. Firemen come rushing up through the garden. Rolling out hoses to train over the wall. Flattening out Dad’s delphiniums on the way. They’re astonished to find us sitting quietly sitting in our hole in the ground. “Get out!” they urge

“It’s about to go up! Make a run for it!” So we all troop off, trying to look as if we’re not in a hurry, to the public shelters on Hackney Marshes. Underground trenches, dripping with moisture, crammed with people on hard wooden planks, crying, arguing, trying to doze off. It was the longest night of my life. And at first light, after the all-clear, we walk back along Homerton High Street. So sure am I that our house had been burnt to a cinder, I can hardly bear to turn the corner into Digby Road. But it’s still there! Untouched! Unbowed! Firemen and hoses all gone. Everything remarkably normal. I feel a pang of guilt at running away and leaving it to its fate all by itself. Make it a silent promise that I won’t do it again. A promise that lasts for just two more nights of the blitz.

I hear it coming from a long way off. Through the din of gunfire and the clanging of fire engine and ambulance bells, a small, piercing, screeching sound. Rapidly getting louder and louder. Rising to a shriek. Cramming itself into our tiny shelter where we crouch. Reaching a crescendo of screaming violence that vibrates inside my head. To be obliterated by something even worse. A gigantic explosion that lifts the whole shelter…the whole garden…the whole of Digby Road, a foot into the air. When the shuddering stops, and a blanket of silence comes down, Dad says, calm as you like, “That was close!”. He clambers out into the darkness. I join him. He thinks it must have been on the other side of the railway. The glue factory perhaps. Or the box factory at the end of the road. And then, in the faintest of twilights, I just make out a jagged black shape where our house used to be.

When dawn breaks, we pick our way silently over the rubble of bricks and splintered wood that once was our home. None of it means a thing. It could have been anybody’s home, anywhere. We walk away. Away from Digby Road. I never even look back. I can’t. The heavy lead weight inside of me sees to that.

Just a few days before, one of the van drivers where Dad works had handed him a piece of paper. On it was written the name and address of one of Dad’s distant cousins. Someone he hadn’t seen for years. May Pelling. She had spotted the driver delivering in her High Street and had asked if he happened to know George Houser. “Of course — everyone knows good old George!”. So she scribbles down her address, asks him to give it to him and tell him that if ever he needs help in these terrible times, to contact her. That piece of paper was in his wallet, in the shelter, the night before. One of the few things we still had to our name. The address is 102 Osidge Lane, Southgate.

What are we doing here? Why here? Where is here? It’s certainly not Isleworth - but might just as well be. The tube station we got off said ’Southgate’. Yet Dad said this is North London. Or should it be North of London? Because, going by the map of the tube line in the carriage, which I’ve been studying, Southgate is only two stops from the end of the line. It’s just about falling off the edge of London altogether! And why ‘Piccadilly Line’? This is about as far from Piccadilly as the North Pole. Perhaps that’s the reason why we’ve come. No signs of bombs here. Come to that, not much of the war at all. Not country, not town. Not a place to be evacuated to, or from. Everything new. And clean. And tidy. Ornamental trees, laden with red berries, their leaves turning gold, line the pavements. A garden in front of every house. With a gate, a path, a lawn, and flowers. Everything staked, labelled, trimmed. Nothing out of place. Except us. I’ve still got my pyjama trousers tucked into my socks. The girls are wearing raincoats and headscarves. Dad has a muffler where his clean white collar usually is. Mum’s got on her old winter coat, the one she never goes out in. And carries a tied up bundle of bits and pieces we had in the shelter. Now and again I notice people giving us a sideways glance, then looking quickly away in case you might catch their eye. Are they shocked? embarrassed? shy, even? No one seems at all interested in asking if they can help this gaggle of strangers in a strange land. Not even the road sweeper when Dad asks him the way to Osidge Lane.

The door opens. A woman’s face. Dark eyes, dark hair, rosy cheeks. Her smile checked in mid air at the sight of us on her doorstep. Intake of breath. Eyes widen with shock. Her simple words brimming with concern. “George! Nell! What’s the matter?” Mum says:” We’ve just lost everything we had” An answer hardly audible through the choking sob in her throat. Biting her lip to keep back the tears. It was the first time I’d ever seen my mother cry.

We are immediately swept inside on a wave of compassion. Kind words, helping hands, sympathy, hot food and cups of tea. Aunt May lives here with her husband, Uncle Ernie and their ten-year-old daughter, Pam. And two single ladies sheltering from the blitz. Five people in a small three-bedroom house. Now the five of us turn up, unannounced, out of the blue. With nothing but our ration books and what we are wearing. Taken in and cared for by people I’d never even seen before.

In every way Osidge Lane is different from Digby Road. Yet it is just like coming home. We are safe. They are family. For this is a Houser house.

Contributed originally by Franc Colombo (BBC WW2 People's War)

ENGLAND PART FOUR

When we got ashore we were met by nurses and volunteer women who made a fuss of us then took us to a big marquee given tea and sandwiches then to a room where our pay book was checked then given travel warrants and told to report to our depot. I arrived at Hounslow in the evening, after settling down I phoned my father to say that I was safe he was pleased to hear from me because by that time he heard the news of the evacuation, in due course the remainder of the battalion arrived, I learnt that quite a few were killed, wounded or missing, fortunately my friends where O.K, finally I met up with my officer and he wanted to know what happened to me. Soon as we were refitted we were posted on the Isle of Wight, we were expecting the Germans to invade, we had few weapons one rifle between two men some just had pitch folks or pick handles, bit by bit we received new weapons, by this time the battle of Britain started, we heard that London and other cities were being bombed, we had our share one bomb dropping on the cook house causing many casualties, luckily it was not meal time.

Our next move was back on the mainland doing training and route marches of twenty miles. I was due to go on leave but before going I had to see the company commander who told me that being Italy declared war on England and being that I came from an Italian family there was the possibility that if I was captured I could be shot therefore I could transfer to a non combat unit I told him that England was my country. When I got home I told my father about it and he told me that I should fight for my country, he also told me that Bastiano and Armando had been interned and he was trying to get them released.

Armando was interned because his mother Fernanda never liked England and sent him to an Italian school and was registered as a fascist. I remember one time when I visited Jinnie and fernanda was there and she said that she could not understand how I could go and fight against the Italians, I told her that they declared war on my country and if I came up against them so be it.

When I went round London I saw the destruction the bombers made, where houses and shops stood there was just a gap and rubble, fortunately round Edgware road they had no damage. In the evening I would visit my friends and we would go to the west end, for a drink it was strange to see so many uniforms and nationalities, many times we had to take shelter because of the raids. While I was on leave I contacted the red cross to see if I could get a message to Tinuccia, I was able to send a card to say that I was well, later we were able to correspond more frequent. Shortly after returning from leave we moved to Newbury, we were billeted on the racecourse just on the edge of town which suited everybody, Newbury was a friendly town and had quite a few places for entertainment.

While we were there Capt. Hill told me that he was being posted to another battalion and would I go with him, I told him that I had applied for a transfer to the airborne division and therefore I would not join him. On the 13th Dec. 1941 we went to Invarery Scotland for combined operation training, we had to live on board a ship in the middle of the lake and sleep in hammocks, we had some fun trying to swing into them but we soon got the hang of it, then we had to learn how to scramble up and down the side of the ship by a rope ladder into an assault craft, in the beginning we found it hard going but after a few times we were going up and down like monkeys. The exercise was landing on the beaches.

We had Christmas dinner with a pint of beer on the ship the rest of the day was our own. The following day the C. O. thought it would be a good idea that after all that food and drink we consumed the previous day we should sweat it out, so we were put ashore by platoons and do a thirty miles march finishing going up a steep hill which terminated on top of a cliff and scrambling down a rope and back to the ship . When our training was over we returned to Newbury, by this time I was receiving letters from Tinuccia, few and far between but at least I knew she was alright and that the feeling for each other was the same, in her letter she told me that one of her cousins had gone to Tunis and that she gave her some letters for me and that if ever I was there I could pick them up.

Our next move was to Camberly, in between manoeuvres we had a visit by King George the VI. I remember that it was a very cold day and light snow on the ground, it was decided that he would come and see us doing training in a field, our company was chosen to do physical training, we arrived at the field in our greatcoats an hour before he was due. When he showed up we removed our greatcoats and just in shorts and vest started to do P.T. when he saw us apparently he was annoyed and told the officers that we should return to our billets given a hot drink and a rum ration.

In April 1942 we were on the move again back to Scotland but this time we were going to walk, we were supposed to be chasing a retreating enemy, we did 130 miles in seven days. We arrived at Stops camp 5 miles outside the border town of Hawick. Contrary to the reputation that the Scots were mean we found them to be the most generous and kind hearted people we ever met, the hospitality of the habitants of Hawick was overwhelming, every man had a household to which he could go when he was in town and be sure of a meal, my friend Frank Vincent and I were taken in by mr. and mrs Nayler and treated as their sons.

Soon after settling down the anti tank platoon was formed I asked to be transfer to it because I was in it when we were in Shornecliff, soon after I was promoted to lance corporal. The training was hard but we were fit, one part was that with my section of 7 men we were taken in the glens miles from anywhere and had to live on the land for 48 hours making our way back to camp using a compass, in the morning we stopped at a farm to ask for some water to make tea, the farmers wife asked us what we had been doing, we told her that we had been out all night she invited us in and gave us a full breakfast and sandwiches to take with us, we finally arrived back in camp, we were not the first but we were not the last.

By this time I was made full corporal in charge of a gun, then came news that we were going on embarkation leave, the train to London did not leave till midnight Mrs Naylor insisted that Frank and I would have dinner with them and made us sandwiches for the journey, the train was packed and we had to sit in the corridor all night. Finely I arrived home and I was told that with fathers intervention Basil and Armando were released from interment. Soon after Armando was called to join the army. I visited all the family because I knew that it would be a long time before I would see them again, I shut it out of my mind that I might never return.

Then I visited my friends and as luck would have it they were also on leave therefore it was an occasion for a celebration and going to the West End and having a good time, one night we went to see Gone with the Wind, it was the rage then. All to soon leave came to an end I told father that it would be sometime before I would see him again, so I returned to Stobs Camp. We learned that we were moving out in a few days, Frank and I went into Hawick to say our farewells to the Naylers, they were sorry to see us go and wished us luck and a safe return.

The following night 9th of March we marched to the station and boarded the train for Liverpool the port of embarkation.

We went on board and taken to our allotted space, it was cramped but we soon sorted ourselves out and we had our old friend the hammock, then with Polly and some other chaps went on deck to have a look round saw some other ships which would make up the convoy. Our ship was the S.S. Cuba a French ship. The following we were shown our boat stations and boat drill.

Two days later we set sail and taking our position in the convoy. In the bay of Biscay I found it difficult moving around and I was seasick but it soon passed and I got my sea legs, it felt strange because I could move around without feeling the lurching of the ship. The days passed with P.T. lectures boat drills and other activities, several times we had air raids, guns going off every where then we went though the Strait of Gibralter and into the Mediteranian, then one day we were attacked by submarines, they managed to sink two ships, one was a troop ship the Winsor Castle, we were at our boat station and saw her sinking, the destroyers chasing every where dropping depth charges then picking up survivors. The following day we sighted Algiers, it was impressive with its white tall buildings, it looked nice till we landed.

Contributed originally by Leicestershire Library Services - Coalville Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

"This story was submitted to the People's War site by Lisa Butcher of Leicestershire Library Services on behalf of Len Taylor and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions."

In 1939 when rumours of war began to spread and the six month’s conscription started I was just too old to be included in that and before any of the chaos who were called up had finished their six months, war was declared on Sunday 3rd September 1939 by the Prime Minister broadcasting to the Nation at 11.00am.

As were most mothers with sons of the right age for call up, my mother was in tears, my father, who was an Overman at Whitwick Colliery, offered to get me a job down the pit. I told him I could not live with that, but promised I would not volunteer, but if called up for conscription I would have to go for my own conscience.

I was of course, soon called up and my first preference was to be in the RAF as a Rear Gunner, but I failed a very strenuous medical and was turned down.

In due course I was called up to the Army to be a Gunner in the Royal Artillery, along with a few other local chaps, one being Jack Walker from Heather.

We had to report to the RA Barracks at Oswestry, it was a dark day to remember, getting off the train at a small station near the Barracks. We were ordered to form three ranks on the platform, where a rather large Sergeant Major addressed us by saying he had seen a lot of recruits coming in but we were about the worst shower he had seen and promised to knock hell out of us until we became good soldiers – they certainly took great pride in making you feel uncomfortable.

We were marched to the Barracks and shown where and how we would live for the next three months. I will never forget the first dinner that evening – potatoes and cabbage were the strangest colour I had ever seen and tasted even worse than they looked, with all the eyes in the potatoes looking at you and daring you to eat them. It really wasn’t a grand welcome.

The next day we collected our uniforms, the only things that fitted were your boots. If any of the rest fitted, you were accused of being deformed.

Then came the first parade of this motley looking mob and the first thing was the order for haircuts, anything less than a crew-cut you were ordered back again, however we survived those first few days and got down to serious training of both our minds and bodies. I think our bodies probably suffered the worst.

That kind of training finished with a series of inoculations, I shudder to think what could have happened with these, judging by today’s standards. We were lined up and the “Doc” had one needle which he kept filling up and jabbing away as fast as he could. Some fainted and he just jabbed them where they lay, and for some hours later, slowly but surely everyone went down to the T.A.B. inoculations, which seemed to give you malaria instead of protecting you against it.

After those three hectic months when most of us had been knocked into shape and the rest left behind, we were sent to a firing camp on the Welsh Coast, to put into practise when we had been taught – anti-aircraft Guns.

We first had to go into a Gun Pit whilst anther Gun Team were firing the Guns, to allow us to get accustomed to the noise. It was an experience to begin with; some men couldn’t stand the noise and had to be taken off the Guns, but once we got going it was almost fun competing against each other for the best Gun Team.

On finishing our live ammunition gun training we were given seven days leave. I took this opportunity to marry the girl of my dreams. Getting all of that fixed up took half my leave, but I was a very happy man for a few days but reality came back and I had to return to the Army.

On getting back to my Regiment we were told that the Blitz on London had started, and we were sent to form the first Anti-Aircraft Division, whose task was to defend the capital. We had some very interesting and sometimes frightening experiences during that time.

One of the first things I remember about the Blitz was arriving on the outskirts of London, where we took over a gun site with four 3” Naval Guns and a Command Post. We thought these guns looked rather small, as we had done all of our training on much larger guns and had got familiar with the blast, so when we got called out on the same afternoon to intercept three Stuka Bombers, we manned the guns without our ear plugs.

The Bombers attacked the factories we were guarding, so we opened up with our ‘small’ guns but soon realised our mistake when our ears were badly punished. We had not realised that the smaller the shell in artillery the worse the crack of sound. As the guns get larger the sound from them develops from a crack which really hurts your ears to a sound more like a roll of thunder which is not so painful. We were very careful to wear our earplugs after that lesson.

We used to wear a special shoulder flash, which was a picture of a German Dornier Plane with a sword through the middle. Most Londoners recognised this flash on our uniform and so we received rather special treatment – cinemas either didn’t charge us at all or only a token charge, and we often had more free beer in pubs than was good for us in appreciation of our efforts to defend London.

We stayed in London all through the Blitz, but not in the same place for long. We were on Gun Sites across London, after getting bombed and set on fire with incendiary bombs.

One night I was off duty and down at the nearest pub for the kind of medicine that might have got you some sleep, when a bomb fell outside our pub and blew the front in. In the scramble that followed I picked up a tea plate with the pub’s name on it as a souvenir of that evening. I still have that plate, it even has the landlord’s name on it. I have considered for the last fifty odd years whether to own up to this theft and take my punishment, but I don’t even know if the pub still exists. Its name was ‘The Robin Hood’ in Anerly Road.

During this time the civilians were wonderful. Just imagine living near to a Gun Site with sometimes as many as sixteen heavy guns firing for most of the night. We used to see them open the front doors every morning and part of the routine of their cleaning was to sweep out all of the fallen plaster from their walls and ceilings, while feeling very pleased that they still had the building standing up.

When bombing first began on London it could be a little un-nerving if you happened to be caught on the Underground Tube Trains between stations under the Thames. This was because they stopped these lines and closed flood doors in case a bomb penetrated the river and flooded the Tube, in other words you were the sacrifice to stop the flooding becoming general. This practice was eventually dropped.

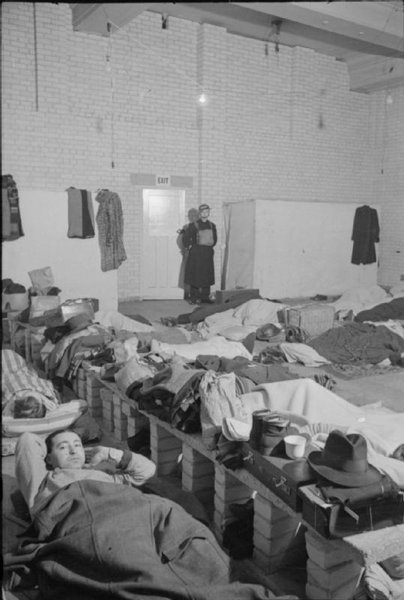

Of course, the Tube stations were used as Air Raid Shelters, thousands of people slept down there every night from September 1940 until May 1941 which was the worst time of the Blitz.

One site we set up at Wellington a few miles from Croydon Airport was a secret Gun Site that was camouflaged during daylight. Next to it was built a ‘Dummy Air Strip’ where fire was started at dark hour to make the German aircraft think they had set fire to Croydon Airport and drop their bombs on that and we would attempt to bring them down. It was terrible for the people who lived in that area as they were a constant target.

We had many lucky escapes. One I remember very well; a bomber approached our gun site and let go with a stick of three bombs. The first exploded about 100 yards short of our guns, the second bomb fell right inside the next gun pit to ours but did not explode. It buried itself in the ground and tipped the gun nearly on its side. The other bomb exploded some 100 yards further away from us-boy what luck!

After the raid was finished and not knowing when the bomb might explode, we took turns going into the gun pit carrying a round of ammunition weighing 56 pounds each. There were hundreds in the gun pit and lucky for us the bomb did not go off. When day-light arrived so did an Army Bomb Squad to diffuse and dig out the bomb, which was a large 500 pound bomb that fortunately did not have any of our names on.

After the bombing died down we had a rather quiet time waiting for something to happen. During this time the film industry decided to make a film record of events as they occurred. We were asked to help by becoming extras. Some of us dressed up as soldiers returning from Dunkirk and others dressed as Germans to take part in mock battles. The star was Jimmy Hanley. We didn’t get paid but it was some light relief for the normal duties of being a soldier.

We then began training for the D-Day landings. We had to learn to use our heavy guns not only against aircraft but against tanks, also as Field Artillery and as Coastal Artillery against any enemy shipping that might arrive anywhere near us. It was hectic training that took us all over Britain, and we eventually passed out as being ready for the Big Day.

During the first few days before D-Day we had to waterproof everything, which involved filling every nook and cranny with Bostik, which came in five gallon drums and was like a kind of sticky grease whose object was to keep the sea water out of vital parts of our equipment. We finished this filthy task and were ready for the action when out of the blue came orders for us to de-waterproof. It was a damn sight harder to get off than it had been to put on. However, we were given only a short time to complete this task, and we were rushed to the South East Coast. Of course at this time we didn’t know why but we were soon to learn the hard way.

Through the intelligence they had found out that London was to be attacked by a new secret weapon and with all of our experience during the Blitz we were called to put into practice once more against this new weapon. It soon arrived in the shape of the ‘Flying Bomb’ which was a pilot-less aeroplane timed to reach London and run out of fuel crashing down with a mighty explosion. It was a frightening thing to begin with, but became almost a competition to see how many could be shot down before reaching the coast line.

We stayed there for a few days whilst a new line of defence was established down the coast line, then we were released for the invasion of France.

This is a rough sketch of my first few years in the Army. New experiences were in store for us once we got into Europe.

I would like to add that during this time I had received some leave and as a result my wife and I were blessed with a lovely son and on embarking for France I left my wife behind, having done the same trick again. Good stuff these army rations!

Contributed originally by cambslibs (BBC WW2 People's War)

------------

First I must say a few words about my parents. My father, a classical violinist, had been badly hit by the slump in the British music world of the mid-thirties, and had been forced to look for other work. He started up in business in catering. He was no business man, and my mother, always the practical one, helped to build up "Always Ready" catering service into a quite successful enterprise. Unfortunately the outbreak of war in 1939 caused a sudden collapse in orders, with many contracts being cancelled, and my father decided to close down. He was very keen to get back to his army days of the first world war, but he was too old and unhealthy to be accepted for military service, so he applied for a civilian job at HQ Eastern Command at Hounslow Barracks. He became a clerk in the Army Pay Corps, and later was transferred to an Army depot in Feltham. My mother heard that the depot were having trouble in finding a manager for their canteen for civilian staff, and applied for the job. Her experience with "Always Ready" made her the ideal person, and she was soon very happily employed, coping with all the difficulties of wartime catering.

At the beginning of 1940 I was still at school. I was coming up to my 16th birthday, and preparing to take London Matriculation soon. I went to a small private school which was owned by a retired Indian Army Officer, who couldn't wait to get back into uniform. After a very difficult period of trying to find suitable staff to take over, he suddenly joined up, and said the school would close down at the end of the summer term. I and a few others were left in a predicament; my mother tried to get me into a local secondary school, but because I had not sat for the 11+ (then called the Scholarship) exam., I could not be accepted. There were no other schools of the required standard around, so we decided that I should continue my studies at home with a part-time private tutor, if one could be found. Luckily we found a local teacher who was very ready to augment her low salary by some coaching work after school. She offered to help with English, French, Latin and History, but couldn't help with the Maths. I decided that, with a bit of hard work with the text book, I could manage that subject on my own; Maths had always been my favourite subject and I looked forward to the challenge.

The first few months of 1940 were rather quiet; I don't think I had any true realisation of what must inevitably happen. The first rumblings of Hitler's intentions began - the German war mahine was on the march. We no longer sang about hanging our washing on the Seigfreid Line, and the British and French armies were being pushed back. The Low Countries were invaded. Queen Juliana and the Dutch government came over to London, to continue their fight; the Belgian King decided to make a truce, thus trapping many of our troops who had gone in to help. The full force of the German offensive was directed at France, and our British Expeditionary Force was pushed back further and further towards the coast. Paris fell and I remember feeling a deep sorrow I could not explain, then the final blow came: France decided to capitulate and our Channel Islands were occupied. We held our breath, what had happened to our troops? Several days passed, there was no news for the anxious relatives, but there was a general feeling that something momentous was about to happen. Suddenly fleets of trains began to deliver exhausted soldiers into London, and as quickly as they could be dispersed, more arrived from the south coast ports. The Dunkirk evacuation had occurred and we cheered as though we had won a victory, which in some ways, we had. Many French soldiers had come over from Dunkirk, and General de Gaulle wasted no time in forming the Free French Army. Everywhere in London were groups of soldiers and airmen from our allies, and there was a determination that we would all see it through together. We must have looked a pathetic little lot to the German High Command.

Now we held our breath again. It seemed pretty obvious that we would be the next target for invasion. Even to the mind of a very naive schoolgirl it was impossible for us to survive such an attack. I must have been still a silly child at heart, because I remember being very determined in how I would behave when the enemy arrived. I would never co-operate under any circumstances! I would join an underground movement and fight on! I think my main concern was that, if the church bells rang (the signal that invasion had begun), my parents, working at Feltham, would be outside the road blocks, part of the London defences, and I would be alone inside. As history will tell you, the attack came from the air. The Battle of Britain began. Luckily, I lived in an area well away from the overhead battles, but I saw squadrons flying out and I remember counting the planes back in. They used to fly in formations of six as I remember it, and sometimes when six returned, one of the boys from the back used to break off into the victory roll. I believe that this behaviour was frowned on by their superior officers, but most of them were just enthusiastic boys who needed to let off steam. I still remember the glorious weather of that September, the warm sunshine by day, and the clear moonlight nights which gave the bombers a clear view of London beneath.

Up to this time I hadn't seen or heard an enemy plane, or heard any ack-ack (gunfire), then one night we heard the air raid siren, and we dutifully went down into the Anderson shelter my father had dug into our garden. As we were going in, we looked towards a glow in the Eastern sky. It grew larger and redder, but still no sound of gunfire. We learned next day of the terrible raid on the docklands and when the same thing happened on the next night, people began to ask why we appeared to have no defence. I believe that it had been thought that if London were declared to be an "Open City", that is, with no military targets, it would not be bombed! The next night we heard gunfire. It was only light anti-aircraft fire but it terrified me; however I soon got used to the "Woomp-woomp" which later seemed a very mild sound compared with the heavy stuff that moved into a nearby field. There was also a mobile gun which roamed the streets, and would suddenly open fire with a very loud BANG just outside the house. My father, after two nights in the Anderson, declared that he was going to his bed in the house; he said that Hitler was not going to make him uncomfortable every night, and that if the house came down, he would be on top of the rubble, still in his bed. My mother and I remained in our garden shelter for a few weeks, but as the evenings got longer and the raids did also, we began to have doubts. A heavy rainfall and an earwig crawling into my ear, rather settled the matter - the shelter flooded and we moved out, never to return.

Later in the war we were given a Morrison table shelter, which we used during the doodle-bug attacks, but for the rest of the raids we slept downstairs in nice comfortable beds. I remember that I slept through some of the heaviest raids.

It is hard to describe what life was like during the autumn and winter that year. Every morning we got up, pleased to have survived the night, and just got on with the daily routine. Rationing was beginning to cause shortages in certain commodities, and while we had our essentials, there were always things we felt we needed. Queueing started when any little extra came into a shop, and I remember the rush to the fish shop when a small amount was delivered. It was first come, first served. I don't think the really biting shortages came until much later than 1940. We began to learn the art of make-do and mend. In the meantime my studies progressed, and I felt I should be ready for my exam. next summer. Because I was at home during the day, I didn't try at this time to study in the evenings. I used to try to relax by listening to the radio, but most nights it could be very difficult, owing to the interference when the planes were about. I never knew what caused the interference but wonder now, if it was something to do with radar which I didn't know much about at the time. In the mornings, the garden was often covered in little strips of metal foil, another unexplained thing. My hobby at that time was picking up the dozens of lumps of shrapnel, dropped by the exploding shells from our guns. Occasionally the Germans had dropped a few leaflets which never seemed very interesting to me. I think we must have become immune to noise, as the raids started as soon as it was dark, and went on until daylight; there were very few planes getting through in the daytime, except occasionally on a heavily clouded day.

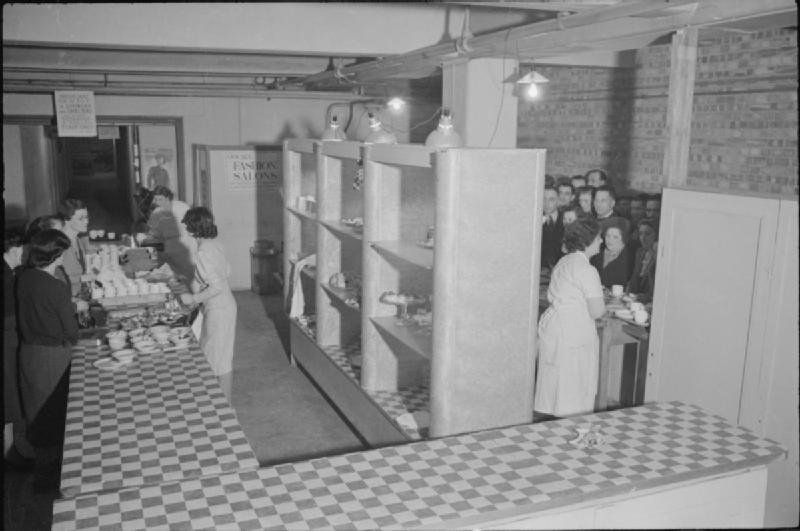

Life in central London went on very much as usual, apart from the clearing up after the night before, the Heavy Rescue squads busy at their often grisly task, the firemen damping down the fires, and everyone being extraordinarily cheerful. I remember going, with my mother, to the theatre during the morning, so that we could be home before the sirens started. Travelling in on the tube with their netted windows, with the little spy hole in the middle, we could work out where the worst raids had occurred during the previous night. The tiles on the roofs would be standing to attention, curtains stripped by flying glass, doors and windows missing, and sometimes just piles of new rubble. The platforms of the deep stations had been taken over for night sheltering, and the walls were lined with bunk beds. No part of greater London escaped the raids, and my western suburb had its fair share. We had various military targets nearby and we felt the occasional "near miss". Sometimes an unexploded bomb arrived, and surrounding buildings had to be evacuated until the Bomb Disposal soldiers had been. On one tragic occasion the bomb blew up, demolishing two houses, and killing the four soldiers who had gone to remove it. Several people died in my area, but none were particularly close, except for one. She had been a fellow pupil at my school, and during one of the rare daylight raids, had gone into her Anderson to shelter; she was killed by a direct hit on the shelter, while her house remained scarcely damaged.

During all this nightly mayhem, my father decided to tour central

London air raid shelters with a group of fellow musicians, "to cheer people up". With the kind of very highbrow music they played, I rather doubt if it had the desired effect, though I believe people did thank them very profusely. Occasionally during a heavy raid, we would stand under our front porch to watch the "firework" display. It was stupidly dangerous, but I have a vivid memory of one night. There were planes caught in searchlights, shells firing up all over, a parachute caught in a searchlight with something very large hanging from it, gently floating down. There were tracer bullets being fired at the flares which illuminated the scene, and there was another parachute which appeared to be throwing out smaller objects as it descended; was this the one they called a Molotov Cocktail?

I do not remember feeling particularly unhappy throughout this difficult period, though I did often wonder whether I would survive.

Somehow we took each day as it came, happy in our togetherness with everyone around us, laughing at the funny things that sometimes happened: the day our next door neighbour turned on her gas cooker, and water squirted from the rings; the night a frantic air raid warden dashed up and down the road, begging people to turn their lights off, when a bomb explosion smashed all the windows and turned the room lights on. There was no TV of course, but we had the radio, and we thoroughly enjoyed ITMA, "Life with the Lyons"(Ben Lyon and Bebe Daniels), Workers' Playtime, and dozens more. Another amusement for some of us was to tune in to Lord Haw-Haw. Much to our government's surprise, he was a huge joke to most young people; they thought he would be bad for our morale. I think the government often underestimated the young at that time!

Christmas came, and "goodwill to all men" must have prevailed, because the raids suddenly stopped, and we had peace over the period.

I believe that this four months of Autumn 1940 was London's finest hour, and I am very proud to have played a tiny part in it.

Contributed originally by vcfairfield (BBC WW2 People's War)

Over the Seas Two-Five-Four!

We’re marching right off,

We’re marching right off to War!

No-body knows where or when

But we’re marching right off

We’re marching right off - again!

It may be BER-LIN

To fight Hitler’s KIN

Two-fifty-four will win through

We may be gone for days and days — and then!

We’ll be marching right off for home

Marching right off for ho-me

Marching right off for home — again!

___________________________

Merry-merry-merry are we

For we are the boys of the AR-TIL-LER-Y!

Sing high — sing low where ever we go

TWO-FIVE-FOUR Battery never say NO

INTRODUCTION

The 64th Field Regiment Royal Artillery, Territorial Army has roots going back to the 1860’s. It first saw action in France during the Great War 1914 to 1918 when it took part in the well known battles of Loos, Vimy Ridge, River Somme, Ypres, Passchendale, Cambrai and Lille.

Its casualties numbered 158 killed.

Again in the Second World War it was called upon to play its part and fought with the 8th Army in Tunisia and then with the 5th and 8th armies in Italy. It was part of the first sea borne invasion fleet to land on the actual continent of Europe thus beginning its liberation from Nazi German domination. Battle honours include Salerno, Volturno, Garigliano, Mt Camino, Anzio, Gemmano, Monefiore, Coriano Ridge, Forli, Faenza, R. Senio Argenta.

Its peacetime recruits came mainly from the Putney, Shepherds Bush and Paddington areas of London up to the beginning of World War II. However on the commencement of hostilities and for the next two years many men left the regiment as reinforcements and for other reasons. As a result roughly one third of the original Territorials went abroad with the regiment, the remainder being time expired regular soldiers and conscripted men.

Casualties amounted to 84 killed and 160 wounded.

In 1937 I was nineteen years old and there was every indication that the dictators ruling Germany in particular and to a lesser degree Italy, were rearming and war seemed a not too distant prospect. Britain, in my opinion had gone too far along the path of disarmament since World War I and with a vast empire to defend was becoming alarmingly weak by comparison, particularly in the air and on land. It was in this atmosphere that my employers gathered together all the young men in their London office, and presumably, elsewhere, and indicated that they believed we really ought to join a branch of the armed forces in view of the war clouds gathering over Europe and the hostile actions of Messrs Hitler and Mussolini. There was a fair amount of enthusiasm in the air at the time and it must not be forgotten that we British in those days were intensely proud of our country. The Empire encompassed the world and it was only nineteen years since we had defeated Imperial Germany.

The fact that we may not do so well in a future war against Germany and Italy did not enter the heads of us teenagers. And we certainly had no idea that the army had not advanced very far since 1918 in some areas of military strategy.

In the circumstances I looked round for a branch of the forces that was local to where I lived and decided to join an artillery battery at Shepherds Bush in West London. The uniform, if you could call the rather misshapen khaki outfit by such a name, with its’ spurs was just that bit less unattractive than the various infantry or engineer units that were available. So in February 1937 I was sworn-in, with my friend Ernie and received the Kings shilling as was the custom. It so happened that soon afterwards conscription was introduced and I would have been called up with the first or second batch of “Belisha Boys”.

I had enlisted with 254 Battery Royal Artillery and I discovered, it was quite good so far as Territorial Army units were concerned, for that summer it came fourth in Gt Britain in the “Kings Prize” competition for artillery at Larkhill, Salisbury. In fact I happened to be on holiday in the Isle of Wight at the time and made special arrangements to travel to Larkhill and join my unit for the final and if my memory serves me correctly the winner was a medium battery from Liverpool.

My job as a “specialist” was very interesting indeed because even though a humble gunner — the equivalent of a private in the infantry — I had to learn all about the theory of gunnery. However after a year or so, indeed after the first years camp I realised that I was not really cut out to be a military type. In fact I am in no doubt that the British in general are not military minded and are somewhat reluctant to dress up in uniform. However I found that many of those who were military minded and lovers of “spit and polish” were marked out for promotion but were not necessarily the best choices for other reasons. There was also I suppose a quite natural tendency to select tall or well built men for initial promotion but my later experience tended to show that courage and leadership find strange homes and sometimes it was a quiet or an inoffensive man who turned out to be the hero.

Well the pressure from Hitler’s Germany intensified. There was a partial mobilisation in 1938 and in the summer of that year we went to camp inland from Seaford, Sussex. There were no firing ranges there so the gunners could only go through the motions of being in action but the rest of us, signallers, drivers, specialists etc. put in plenty of practice and the weather was warm and sunny.

During 1939 our camp was held at Trawsfynydd and the weather was dreadful. It rained on and off over the whole fortnight. Our tents and marquees were blown away and we had to abandon our canvas homes and be reduced to living in doorless open stables. Despite the conditions we did a great deal of training which included an all night exercise. The odd thing that I never understood is that both in Territorial days and when training in England from the beginning of the war until we went abroad there was always a leaning towards rushing into action and taking up three or four positions in a morning’s outing yet when it came to the real thing we had all the time in the world and occupying a gun site was a slow and deliberate job undertaken with as much care as possible. I believe it was the same in the first World War and also at Waterloo so I can only assume that the authorities were intent on keeping us on the go rather than simulating actual wartime conditions. Apart from going out daily on to the firing ranges we had our moments of recreation and I took part in at least one football match against another battery but I cannot remember the result. I always played left back although I really was not heavy enough for that position but I was able to get by as a result of being able to run faster than most of the attacking forwards that I came up against.

The really odd coincidence was that our summer camp in Wales was an exact repetition of what happened in 1914. Another incident that is still quite clear in my memory was that at our Regimental Dinner held, I believe in late July or early August of 1939, Major General Liardet, our guest of honour, stated that we were likely to be at war with Germany within the following month. He was not far out in his timing!

Well the situation steadily worsened and the armed forces were again alerted. This time on the 25th August 1939 to be precise. I was “called up” or “embodied” along with about half a dozen others. I was at work that day at the office when I received a telephone call from my mother with the news that a telegram had been sent to me with orders to report to the Drill Hall at Shepherds Bush at once. This I had expected for some days as already more than half the young men in the office had already departed because they were in various anti-aircraft or searchlight units that had been put on a full war footing. So that morning I cleared my desk, said farewell to the older and more senior members who remained, went home, changed into uniform, picked up my kitbag that was already packed, caught the necessary bus and duly reported as ordered.

I was one of several “key personnel” detailed to man the reception tables in the drill hall, fill in the necessary documents for each individual soldier when the bulk of the battery arrived and be the general clerical dogsbodies, for which we received no thanks whatsoever. The remainder of the battery personnel trickled in during the following seven days up to September 2nd and after being vetted was sent on to billets at Hampstead whilst we remained at the “Bush”.

The other three batteries in the regiment, namely 253, 255 and 256 were mustered in exactly the same manner. For instance 256 Battery went from their drill hall to Edgware in motor coaches and were billeted in private houses. The duty signallers post was in the Police Station and when off duty they slept in the cells! Slit trenches were dug in the local playing fields and four hour passes were issued occasionally. There were two ATS attached to 256 Battery at that time a corporal cook, and her daughter who was the Battery Office typist.

I well remember the day Great Britain formally declared war on Germany, a Sunday, because one of the newspapers bore headlines something like “There will be no war”. Thereafter I always took with a pinch of salt anything I read in other newssheets.

At this time our regiment was armed with elderly 18 pounders and possibly even older (1916 I believe) 4.5 howitzers. My battery had howitzers. They were quite serviceable but totally out of date particularly when compared with the latest German guns. They had a low muzzle velocity and a maximum range of only 5600 yards. Our small arms were Short Lee Enfield rifles, also out of date and we had no automatics. There were not enough greatcoats to go round and the new recruits were issued with navy blue civilian coats. Our transport, when eventually some was provided, was a mixture of civilian and military vehicles.

Those of us who remained at the Drill Hall were under a loose kind of military discipline and I do not think it ever entered our heads that the war would last so long. I can remember considering the vastness of the British and French empires and thinking that Hitler was crazy to arouse the hostility of such mighty forces. Each day we mounted a guard on the empty building we occupied and each day a small squad marched round the back streets, which I am certain did nothing to raise the morale of the civilian population.

There were false air raid alarms and we spent quite a lot of time filling sandbags which were stacked up outside all the windows and doors to provide a protection against blast from exploding bombs. In the streets cars rushed around with their windscreens decorated with such notices as “DOCTOR”, “FIRST AID”, “PRIORITY” etc, and it was all so unnecessary. Sometimes I felt more like a member of a senior Boy Scout troop than a soldier in the British Army.

After a few weeks the rearguard as we were now called left the drill hall and moved to Hampstead, not far from the Underground station and where the remainder of the battery was billeted in civilian apartments. They were very reasonable except that somebody at regiment had the unreasonable idea of sounding reveille at 0530 and we all had to mill about in the dark because the whole country was blacked out and shaving in such conditions with cold water was not easy. Being a Lance Bombardier my job when on guard duty was to post the sentries at two hourly intervals but the problem was that as we had no guardhouse the sentries slept in their own beds and there was a fair number of new recruits. Therefore you can imagine that as there were still civilians present, occasionally the wrong man was called. I remember finding my way into a third or fourth floor room and shaking a man in bed whom I thought was the next sentry to go on duty only to be somewhat startled when he shot up in bed and shouted “go away this is the third time I have been woken up tonight and I have to go to work in a few hours time!”

Whilst we were at Hampstead leave was frequent in the evenings and at weekends. Training such as it was, was of a theoretical rather than a practical form. However we very soon moved to “Bifrons House” in Kent, an empty stately home in very large grounds near Bridge and about four miles south of Canterbury. Here we resided until the middle of 1940.

In this position we had a bugler who blew reveille every morning while the Union Jack was raised, and lights out at night. The food was quite appalling in my opinion. It was prepared in large vats by a large and grimy cook and by the time it was distributed was almost cold due to the unheated condition of the dining area. Breakfast usually consisted of eggs eaten in the cold semi darkness and the yolks had what appeared to be a kind of plastic skin on them that was almost unbreakable. Indeed all meals were of the same poor standard and there was no noticeable improvement during our stay here.

The winter of 1939/40 was very long, very cold and brought a heavy fall of snow which stayed with us for several weeks. Christmas day was unforgettable. I had a touch of ‘flu and the first aid post where another soldier and myself were sent to was an empty room in a lodge house. There was not a stick of furniture, no heating, the floors were bare and we slept on straw palliasses on the floor. I recovered very quickly and was out in two or three days! On one day of our stay at Bifrons, on a Saturday morning there was a Colonels inspection and as a large number of sergeants and bombardiers were absent from among the gun crews I was detailed to take charge of one gun and stand in the frozen snow for the best part of an hour on what was I believe the coldest day of the winter. And so far as I remember our Commanding Officer decided not to include us and eventually we were dismissed and thawed out around the nearest fire.

In general however I think most of us quite enjoyed our stay here. It certainly was not like home but we made ourselves comfortable and parades finished about 1630 hours which gave us a fair span of time until “lights out”. At weekends we spent the Saturday evening in the pub in nearby Bridge and occasionally walked or begged a lift to Canterbury which was four miles away. In our spare time we played chess and various games of cards. From time to time we were entertained by groups of visiting artists or had sing-songs in typical army fashion. Looking back it was in some ways I suppose like an of beat low class boarding school with the battery numbering some two hundred and fifty men billeted in the bedrooms and stables of the house. Nevertheless we did a lot of training. We even went out in the cold snow covered countryside at night in our vehicles as if we were advancing or retreating, for two or three hours at a time. We had to take a certain preselected route which was very difficult to follow because with everything hidden beneath the snow, with no signposts and with trying to read an inch to the mile map at night with a hand torch giving only a very restricted light because of the blackout the odds against making a mistake were fairly high. We would come back cold and hungry to a mug of hot tea or cocoa and a bite to eat. By day we practised other aspects of artillery warfare either as part of the battery as a whole, sometimes with our signallers but more often as not as a group of specialists going through the many things we had to learn, time after time. When the weather improved this was a most enjoyable way of spending the morning or afternoon session for we could take our instruments out to an attractive bit of the countryside within walking distance of our billets and do some survey, map reading or a command post exercise.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

In 1939, I was ten years old and lived with my family in a terrace house in Catlin Street, off Rotherhithe New Road, Bermondsey, South London.

I had two older brothers, John and Percy, two younger sisters, Iris and Beryl and a little brother Ron. My mother was expecting another baby in December who was to be my sister Sheila.

During the summer, war-scare was the main topic on the radio and in the newapapers, lots of preparations for Civil Defence were started.

Everyone was issued with a Gas-mask in a cardboard box with a shoulder string. Children under five got a "Mickey-mouse" model in pink rubber with a blue nose-piece and round eye-lenses.

There was a special one for infants, which completely enclosed the baby, and came with a hand-pump for Mum to operate.

It was a time of some excitement for us schoolchildren, clouded a little by fear of the unknown. All I knew about war was what mum and dad had told me about the Great War, when dad was a soldier and mum's family were bombed out in a Zeppelin raid when they lived at New Cross, Deptford.

Of course, things didn't happen all at once, you went to collect your gas-mask when it was your family's turn. Similarly, throughout the summer, gangs of workmen came round erecting Anderson shelters in the back gardens, street by street, a slow process. So the main topics of conversation at school were: "Got your gas-mask yet?" Or perhaps: "They've dug a big hole in our back-garden and are putting the shelter in today." This made one quite a celebrity, with looks of envy from others who were still shelter-less.

It was in the summer holidays when we got our shelter, so I didn't get a chance to gloat. Brother Percy remembers getting timber and plywood off-cuts from the local timber-yard to floor it out, but we were never to use this shelter in an air-raid as we moved to our new home in Galleywall Road before the Blitz started.

On the Wednesday of the week before War was declared in September, us school-children were told to pack our things and bring them with us to school next day as we were going to be evacuated from London. Although John and Percy went to different schools, they were allowed to come with Iris, Beryl and myself in order to keep the family together.

We duly turned up next morning with our little bits of luggage and had a label with our details on it tied to our coat lapels. Some of the kids were a bit quiet and weepy, but most were excited and chattering, speculating about where we were going.

Eventually, we walked in a long crocodile all the way to the back entrance of Bricklayers Arms goods station in Rolls Road. An engine-less train stood beside the wooden platform in the dim light of the goods-shed. We all got in and waited for what seemed an interminable time, then we were ushered out again and marched back to school. Our evacuation had been cancelled and we were sent home again. We never heard the reason why, but I think it must have been something to do with the railway being busy with military traffic.

On Friday the 1st of September, we assembled again at school early in the morning and walked in our procession to South Bermondsey Station, just a short distance away, each wearing a label, gas-mask case on shoulder and carrying a case or bag.

This time it was for real, and there was a special electric train waiting at the station, with plenty of room for all of us, but to the consternation of the big crowd of Mums and Dads who came to see us off, no-one could tell them where we were going, so it was a mystery ride.

The old type train carriages had seperate compartments and no corridor, so there were no toilets. I don't remember there being any problems in my compartment, although I was bursting by the time we arrived at our destination, but I expect there were some red faces in the rest of the train, especially among the younger children.

The journey took for ages, as we were shunted about quite a bit, and by mid-day we were getting hungry.

At last the journey ended and we found ourselves at Worthing, a seaside resort on the Sussex coast

Tired and hungry, we were herded into a hall near the station and seperated into groups, family members together.

Some of us were given a white carrier-bag containing rations, which I believe was meant to be given to the people we were billeted on to tide us over, but following the example of my friends, I dived into mine to see if there were any eatables. All the bag contained was a tin of condensed milk, a tin of corned-beef, a packet of very hard unsweetened plain chocolate that tasted like laxative, and two packets of hard-tack biscuits, which were tasteless and impossible to eat while dry. I think they must have been iron-rations left over from the first World-War.

A Billeting Officer took charge of each group and took us round the streets, knocking at doors until we were all found a billet This was a compulsory process, and some of the Householders didn't take too kindly to having children from London thrust upon them, so there were good Billets and not so good ones.

Some would only take boys or girls, but not both if they only had one spare room, so families were split up.

It was all a big adventure for me, and I wanted to stay with my schoolmate, Terry. We had teamed up on a school holiday earlier in the summer, and were good friends.

My two brothers were put into the same billet, and my sisters together in the house next door. They were all well looked after, but Terry and I were the luckiest

We went to stay with Mr and Mrs L at their house in Ashdown Road, Worthing. They had a teenage son and daughter, and Granny L lived in her own room upstairs.

Auntie Mabel, as we came to know Mrs L, was a lovely person. She treated us as if we were her own, and her Husband and the rest of the family were all good to us.

Auntie Mabel was always cooking and baking, and made sure that we ate plenty. Her Husband, who I will call Uncle L as I forget his first name, was a Builder and Decorator with a sizeable business and had men working for him.

He'd spent most of his life in the Royal Navy, and served on the famous Battleship, HMS Barham, during the first World War when it was in the Battle of Jutland. He had many tales to tell of his sea-faring life, and lots of photographs which enthralled me and made me want to be a sailor when I grew up.

His son, I think his name was Dennis, had only recently left school and started work. He became our special friend, and took us on regular outings to the Cinema, sporting events and the like.

His sister was a couple of years older. I don't remember much about her, except that her name was Edna. She was very pretty and worked at the local Dairy.

Granny L was very old. I believe she must have been in her eighties at the time. She used to wear long dresses, and wore her grey hair in a huge bun on top of her head.

She looked just like one of those ladies seen in old pictures of Victorian scenes.

She was very nice, and reminded me a little of my own Gran back in London.

We immediately hit it off together and became firm friends. She had lots of curios and pictures. Her husband had been a Captain on one of the old Sailing-Ships before the age of steam, and sailed all over the world.

He'd spent a lot of time in the South- Seas, and brought many souvenirs home. I remember some lovely Corals in a glass-case, and a couple of the largest eggs I'd ever seen. Granny L said they were Ostrich eggs, and came from Africa.

The L Family were Chapel-goers, and took us to the Service with them every Sunday evening.

It was quite an experience, being so informal after the strict Church Services we were used to at home.

Auntie Mabel looked rather grand in her Sunday clothes.

She used to wear her best coat and a big hat, which I thought was shaped like an American Stetson with trimmings. These hats were fashionable at the time, and it looked good on Auntie Mabel. She was a nice-looking lady, always smiling and joking.

It was a lovely summer that year, and the weather was fine and sunny when we went to Worthing, so we made the most of it and were on the beach on the morning of Sunday September 3.

We heard that Mr Chamberlain had announced on the radio at eleven o'clock that we were at war with Germany. Not long afterwards, we heard the wail of Air-raid Sirens, then the sound of aircraft engines, but it was one of ours and soon the All-clear sounded.

In the ensuing days and weeks, everything seemed to carry on as normal, the Seafront and beaches were open and without any defences, although this was all to change in the coming months.

The following weekend, it was still warm and sunny, and our little group were walking along the crowded Sea-front, when who should appear in front of us, but my Mother, and Auntie Alice, her younger sister.

They had both been evacuated from London as expectant mothers a few days before. Mum had heard rumours that our school had gone to Worthing, but our letters home hadn't arrived by the time she left, so she wasn't sure.

It was by a lucky chance that they'd come to the same place, and they knew we'd be at the Sea-front sometime if we were here, so they kept a constant look-out.

Mum and Auntie Alice were billeted quite a long way from us, so we only saw them at weekends, but it gave us a feeling of security to know that Mum was around.

However, she only stayed at Worthing for a couple of months or so until the first war-scare died down, although we had to stay on as there were no Schools open in London.

Our education carried on as normal at the local Junior School. One thing that stands out in my mind is that after we'd been there a while we were told by the Class-Mistress to write an essay on the most interesting thing we'd found while at Worthing.

At the weekend before, Dennis had taken us up on the South Downs behind the town to Chanctonbury Ring, a large circular clump of ancient trees on top of a hill.

There were prehistoric remains in the vicinity, and it was dark and eerie under the trees, the ring was reputed to be haunted.

There were quite a few tales going the rounds at school about it, especially the one about what happened to you if you ran round the ring three times, then lay down and closed your eyes.

You were supposed to experience all manner of weird things. On reflection, I think one would have needed to lie down after running round the ring three times. You'd have ran at least a couple of miles!

Needless to say, my essay was about our trip to this place, and I was all-agog to read it out in class when the Mistress randomly selected one of us to do so.

However, she chose Ronnie Bates, another friend of mine who lived just round the corner at home, and I can still see the look of horror on the Mistress's face as Ronnie proceeded to read out his lurid essay about the goings on at the local Slaughterhouse, which was on his way home from school, and seemed to fascinate him.

He often managed to get a peep inside, it was an old-fashioned place, and opened on to the street with just a small yard for the animals going in.

In the run up to Christmas, they formed a choir at school, and I was chosen to be a member. Then we were told that the BBC were organising a children's choral concert to be broadcast from a local theatre just before the Christmas Holidays.

Choirs from all the many London schools evacuated to Sussex taking part.

When the day came, we spent all the morning at the Theatre rehearsing with the BBC Orchestra, and Chorus-Master Leslie Woodgate. He was quite a famous man, well known on the radio, and really good at his job, so he got the best out of us.

Even I felt quite emotional when the concert ended with everyone singing "Jerusalem" acccompanied by the full Orchestra.

What seemed strange to me was the way Mr Woodgate mouthed the words at us as we sang, he looked quite comical conducting at the same time.

There was a sort of Lamp-standard with a naked red bulb on the front of the stage, and when it came on, we were on the air!

The Concert was interspersed with orchestral music and soloists as well as our singing. One item that I particularly recall was a piece by a lady Viola player, accompanied by the orchestra.

I had never heard of the Viola before, I just thought they were all Violins except for Cellos and Double-Basses.

The rich tone of the instrument impressed me very much, although at the time I was dying for the Lady to finish playing so that I could dash out to the toilet.

We were afterwards told that the Concert was a big success, but none of us were able to hear it on the radio. It was a live broadcast, as most radio programmes were in those days.

The weekend after school broke up for the holidays, Dad came down in a friend's car and took us home for Christmas.

I didn't know it when we left, but that was the last time I was to see Auntie Mabel and her family, as we didn't go back to Worthing after the holiday, but stayed at home in Bermondsey.

It was the time of the "phony war". Many evacuees returned to London, as a false sense of security prevailed.

Our parents allowed us to stay at home after much worrying. We heard that our School was re-opening after the holidays, and as I was due to sit for the Scholarship, I'd be able to take it in London.

This exam was the forerunner of today's eleven-plus, and passing it would get me a place at one of the private Grammar-Schools with fees paid by the London County Council.

To my great regret, in all the turmoil of events that followed with the start of the Blitz, and my second evacuation from London to join my new School, I didn't keep up contact with Auntie Mabel and her family. I hope they all survived the war and everything went well for them.

{to be continued}.

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

Home again in Bermondsey after the few months sojourn in Worthing, I saw my new baby sister Sheila for the first time. She'd been born on December 5, and Mum was by then just about allowed to get up.

In those days, Mothers were confined to bed for a couple of weeks after having a baby, and the Midwife would come in every day. In our case, the Midwife was an old friend of my mother.

Her name was Nurse Barnes. She lived locally, and was a familiar figure on her rounds, riding a bicycle with a case on the carrier. She wore a brown uniform with a little round hat, and had attended Mum at all of our births, so Mum must have been one of her best customers.

That Christmas passed happily for us. There were no shortages of anything and no rationing yet.

When we found that our school was re-opening after the holidays, Mum and Dad let us stay at home for good after a bit of persuasion.

I was a bit sad at not seeing Auntie Mabel again, but there's no place like home, and it was getting to be quite an exciting time in London, what with ARP Posts and one-man shelters for the Policemen appearing in the streets. These were cone shaped metal cylinders with a door and had a ring on the top so they could easily be put in position with a crane. They were later replaced with the familiar blue Police-Boxes that are still seen in some places today.

The ends of Railway Arches were bricked over so they could be used as Air-raid Shelters, and large brick Air-raid Shelters with concrete roofs were erected in side streets.

When the bombing started, people with no shelter of their own at home would sleep in these Public Air-raid Shelters every night. Bunks were fitted, and each family claimed their own space.

There was a complete blackout, with no street lamps at night Men painted white lines everywhere, round trees, lamp-posts, kerbstones, and everything that the unwary pedestrian was likely to bump into in the dark.

It got dark early in that first winter of the war, and I always took my torch and hurried if sent on an errand, it was a bit scary in the blackout. I don't know how drivers found their way about, every vehicle had masked headlamps that only showed a small amount of light through, even horses and carts had their oil-lamps masked.

ARP Wardens went about in their Tin-hats and dark blue battledress uniforms, checking for chinks in the Blackout Curtains. They had a lovely time trying out their whistles and wooden gas warning rattles when they held an exercise, which was really deadly serious of course.

The wartime spirit of the Londoner was starting to manifest itself, and people became more friendly and helpful.It was quite an exciting time for us children, we seemed to have more things to do.

With the advent of radio and Stars like Gracie Fields, and Flanagan and Allen singing them, popular songs became all the rage.

Our Headmaster Mr White, assembled the whole school in the Hall on Friday afternoons for a singsong.