High Explosive Bomb at Cranworth Gardens

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Cranworth Gardens, Kennington, London Borough of Lambeth, SW9 0AR, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

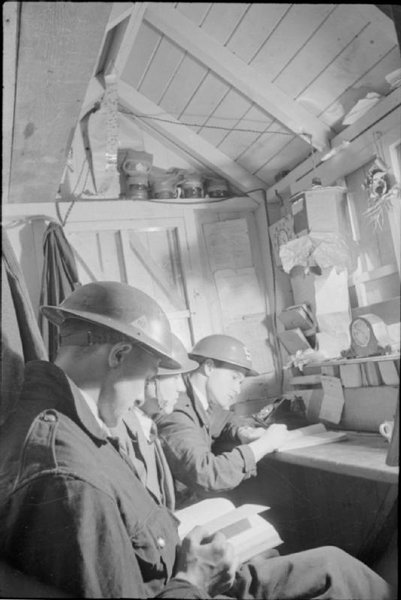

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

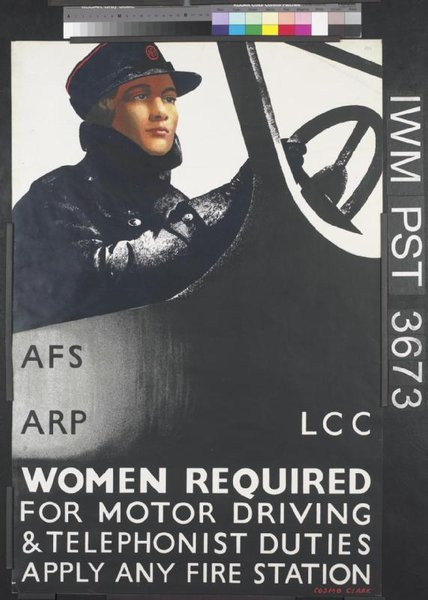

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by Berylsdad (BBC WW2 People's War)

BRAVERY

In those early days of the Blitz, there were many unsung heroes who, by their personal conduct and fervent belief that we could beat the menace of Hitler’s frightfulness, inspired us to carry on and keep London working. So little has been recorded of how this threat to our great city was successfully combated by the ordinary man in the street. As a nation, we are chary of patting ourselves on the back and it is, perhaps, for that reason, that the bravery of so many has been recognised by so few.

Amongst the unsung heroes, there will always remain in my memory a comrade by the name of Edward Bennett of Lyndhurst Way, Camberwell, affectionately known to members of the Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot as “Pop”. It was this oft-blitzed depot that the late Vivian Woodward served and Ted Heming learned first-aid and rescue work that was later to help him to win his George Cross. Cambridge University students also did relief work there and, as a tribute to the staff, afterwards entertained our Depot’s cricket team at Cambridge, where Vivian probably played his last cricket match and Ted was included in the team.

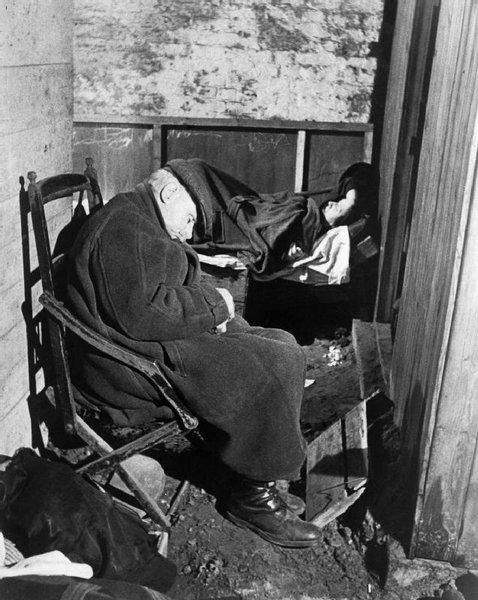

Our “Pop” was nearly sixty years of age when he joined the Civil Defence, his duties covering the period of 24 hours on and 24 hours off. But when the Blitz on London started, Pop, like many others, voluntarily became ‘on-call’ on his off-duty nights and therefore available to fill any gap that might occur in the on-duty ranks. This often meant continual work over thirty-six hour periods. During those hectic days and nights, Pop, if not require for any other duty, would take up position in an ordinary unprotected Sentry Box, situated just outside the Depot, and keep fire-watch whilst indulging in a humorous commentary upon the way “Jerry” was “getting it” in the battle raging overhead. Despite many requests from his friends to take advantage of cover, Pop would still carry on. There is no doubt that his humour and sangfroid did much to raise the morale of his team-mates in those early days. One night, when Pop was out at an incident, the Sentry Box was blown to smithereens by a bomb exploding just outside the Depot. But, box or no box, Pop still continued, in his spare moments, to stand in the same position and his lively commentaries remained unabated. His devotion to duty was tremendous and it is due to this fact that we lost an untiring and heroic figure. The responsibility for his passing lies primarily with the dropping of a large enemy bomb, but the chemical deposits in Mother Earth subscribed in a mysterious way to our loss.

On 4th October, 1940, when Pop was officially off-duty, he reported as usual as being available ‘on-call’. After a quiet beginning to that fateful night, Camberwell soon received its usual strafing. Amongst the quota was a heavy HE bomb that dropped in a garden close to our Depot. The action of the bomb was weird in effect, for although it penetrates the earth very deeply, throwing tons of clay into the adjoining streets, and the explosion severely blasted surrounding houses, there was little sign of a crater, the point of impact only being marked by a ring of fire on the surface of the ground that afterwards was recognised by the experts as due to the ignition of subterranean gases. Some minutes elapsed before Headquarters assigned one of our Parties to cover the incident, but Pop, not bound by the necessity of awaiting an official order, had dashed round to the spot to see if his first-aid qualifications were needed. Happily, except for a few slight shock cases, no-one was injured, but a number of women in nearby Anderson shelters were pleading for the flames, that were now reaching considerable proportions, to be extinguished. At that stage of the Blitz, most people, influenced no doubt by the Official Lighting Order, regarded ground lights of any nature as a greater menace to safety than any danger that existed in the battle raging overhead. The first-aid Party sent from our Depot arrived on the scene to find Pop endeavouring to smother the flames with earth. As they approached, they almost immediately felt themselves being drawn as if by magnetic forces towards the spot from which Pop was operating. Flinging themselves to the ground, they just managed to evade being sucked into the centre of the flames. When they picked themselves up some moments later, the fire had partly subsided, but Pop and a valiant helper had vanished, without a cry or any indication of distress, into the bowels of the earth. Despite frenzied digging by his comrades that night and subsequent weeks of endless toil by specialised rescue teams, not a single particle of clothing or equipment or clue to their whereabouts was then or since discovered. The official theory was that Pop and his friend were drawn by suction down to a subterranean stream for, although powerful pumps were employed, water at 20 feet made further excavation work impossible.

But, though Pop vanished beyond our ken, he will ever remain in the hearts of all who served at Bellenden Road, as a very gallant and unsung hero.

C R Mercer

Superintendent, Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!

Contributed originally by Mike Hazell (BBC WW2 People's War)

BUS STOP

FOREWORD

I still can’t believe it - they don’t want me any more. Twenty-two years of bus conducting - cycling two miles each way to the garage summer and winter - in the rain, sunshine, fog, ice, snow and gales - late turn and early turn - happy in my job I thought - but no more - it’s true - I’ve got to face it - they just don’t want me. Of course I can’t pretend it came as a totally unexpected shock. When I first came to Staines Garage all those years ago there were rumours that the Country Buses might go to Windsor and the red buses of London Transport’s Central fleet take over instead. But we all laughed and said it would never happen and it hasn’t has it? Well, there was a rumour only last week - remember? Not quite the same rumour that went round in the middle fifties mind you - this time it’s just that Staines Garage was closing down completely - well that can’t be true- people will always want buses.

Doris Hazell 1979

Chapter One

The Interview

“People will always want buses - so if you are lucky enough to pass your interviews, the medical tests and the exams at the end of your training course, then you have a job for life - the best paid unskilled labour in the country, a week’s paid holiday a year, smart uniform and a position of trust you can be proud of.” There were about twenty of us sitting around the Recruiting Officer at Chiswick - mostly women because it was wartime and most able-bodied men were in the Armed Forces or reserved occupations. September 1941, I was twenty-one years old and applying for a job as a bus conductor. My mother had done the same in the Great War, 1913-1918, and that seemed a good enough reason when I was asked why I wanted the job. A very smart, efficient-looking girl replied, “Well, sir, we have to keep the wheels turning while the men are over there doing their bit.” and I wished I had thought of something clever like that to say. I bet she still isn’t a bus conductor.

We all handed in our birth certificates - none but solid British Citizens for London Transport in those days - and the married ones among us were asked for their marriage lines. Tragedy struck for a rather pleasant girl that I ‘d taken an instant liking to while we were all nervously awaiting the arrival of the Interviewing Officer. Although she had applied for the job as Mrs Bull she had no official status as such - her man, in the Air Force if my memory is correct, had a wife in a mental asylum and that wasn’t grounds for a divorce in those days - so our Mrs Bull was kindly but firmly shown the door. Poor soul, I suppose she got no marriage allowance from the Government either and I wonder what happened to her. Can you imagine being turned down for a job, any job, for that reason in this permissive age?

We were questioned about our education and previous jobs and I had to admit to nothing grander than a Council School which I had left a few months before my fourteenth birthday and went “into service” as a between maid in a titled lady’s house in Regents Park. I disappointed my teachers who were confident that I would pass my scholarship and enter the local County (Grammar) School, but I had wanted to leave home and be independent. My parents had split up a couple of years earlier and subsequently divorced and, although I got on well with my new step mother, I decided not to be a financial burden on my father, whose second family was already on the way, and left home.

Sensing that a divorce in the family wasn’t enhancing my character in the eyes of the Interviewing Officer, I hurried to explain that when War broke out and my father lost the two men he employed when they were called up, I went back home to help with the family business in Staines, becoming a voluntary Air Raid Warden in my spare time. This dutiful behaviour on my part earned a nod of approval and again the question why was I now applying for the job on London buses? Well, I now lived with my grandmother because she steadfastly refused to be evacuated. Anything further out of London than Greenwich was out in the country to her way of thinking and Cornwall (where her sister had been sent) was practically the ends of the earth. Granddad had been killed by a bomb while at work and my father had given up his business on receiving his own calling up orders, so my removal to 234 New Kent Road, SE1 suited us all.

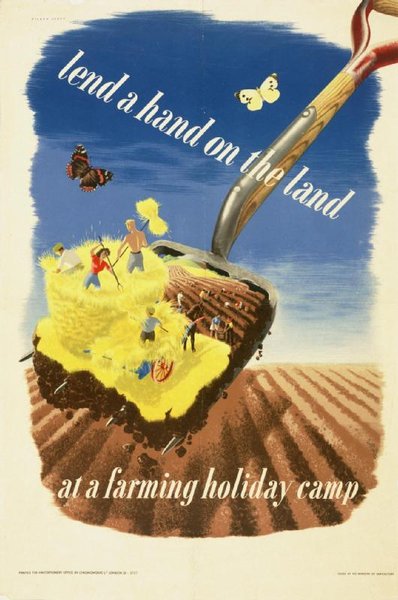

In those Wartime days all young single girls had either to be in a reserved occupation or join the Women’s Army, Navy or Air Force. The reserved occupations included working in factories, making munitions or other essential products, serving in the Auxiliary Fire Brigade, Air Raid Warden’s Service, Ambulance Brigade or Nursing. Although I had been a Air Raid Warden at Staines, the job had consisted mainly of fitting and testing gas masks, advising people how to equip their air raid shelters and answering the telephone in the Warden’s Post. No bombs had fallen on Staines up to that time, though we did see London burning as a red glow in the sky eighteen miles away. But to be an Air Raid Warden in London took more courage than I could muster up and I didn’t think I was tough enough to be a nurse either. Florence Nightingale I was not! My gran had told me horrifying tales of girls in munitions factories in the 14-18 War, getting their flesh eaten away with phosphorous burns, so I wasn’t keen on factory work either, though I guessed that conditions in the factories were bound to be much better in 1941 than in those days. Being in the Armed Services sounded much more glamorous but it wouldn’t be much company for Gran - the Powers-that-Be seeming to take a malicious delight in sending Forces personnel as far away from home as possible, besides, I was waiting for Bill to get his first leave from the Navy so that we could get married so I needed a permanent address when I had to apply for the licence.

All this went through my mind like a flash while the interview was going on, but I decided that none of it left me in a very heroic light, so I just repeated what I had said about my mother being a bus conductor in World War I and fished a rather faded photo out of my handbag to show him - and there she stood. My mum, aged eighteen, dressed in mid-calf length skirt, knee high boots and a big hat turned up one side rather like the Australian troops wore at the beginning of the War. The bus was quite small by today’s standards, twenty-four seats, open top of course, and solid tyres - a B type. I wish I knew what happened to that photo - it got mislaid years ago. But, thinking back on it, mid-calf length skirt and knee high boots would look the height of fashion now!

I don’t think the Interviewing Officer noticed the way my mum was dressed though - it was the photo of the bus that interested him. Apparently there were still a few like that on the road when he started on the buses and he told me how they worked a ten hour day with no meal breaks and got soaking wet going up and down stairs out in the open in the wet weather. Conditions were a lot better now he assured me and he just knew I was going to like being a woman conductor. So then I knew I had passed my interview and sailed off to the medical room to join the other lucky ones waiting to see the doctor.

When my turn came I was asked how tall I was. “Five feet eight and a half,” I said, being proud of the fact that I was rather tall for a woman. “Oh! I hope not,” was the disconcerting reply, “Conductors must be under five feet, eight inches tall or they would have to stoop when collecting fares on the upper deck.” So, standing against the wall measuring scale, I bent my knees just a tiny fraction so that the doctor could put five feet seven and three quarter inches on the application form. Then came a very thorough check-up, for London Transport had an exceptionally high standard and if you passed fit to be a conductor in those days you were fit for anything. Never having anything worse than a slight cold since the measles and chicken pox of my infancy - I hadn’t seen a doctor since the age of seven when, decently dressed in vest and bloomers, I’d passed the doctor’s examination at school - I was still blushing furiously after the thorough going-over in the medical room when, once again clothed, I waited to see the Personnel Officer to find out to which bus garage I was being sent.

To my horror I was told there were no vacancies on the buses and I would have to wait a few weeks before I started my training. I could, of course, work on the trams if I liked, there were a few vacancies at Wandsworth Depot but that was rather a long way from where I lived. In ignorance, I jumped at the chance and was duly assigned to Wandsworth Depot though told I would not see my new place of work until I had done two week’s training at the school. The training school for tram conductors was at Camberwell Depot, which wasn’t too far, being just up the Walworth Road from the Elephant and Castle.

By now it was time for lunch in the staff canteen. There were only ten girls now - half had been dismissed as not up to standard - and we excitedly chattered all through a cheap but good and well-cooked meal. I found that there were three who had decided to wait for a vacancy on the buses, including the smart, efficient girl who had given all the right answers at the first interview. I didn’t think the old jam-jars would suit her image! At this time we were referring to our department by its proper name - we didn’t discover the universally popular nickname till we arrived at our respective depots. The term jam-jar was an affectionate one used by staff and public alike - people actually loved the noisy, old monsters and frequently allowed a mere bus to go by if there was a tram in sight.

So seven would-be tram conductors downed large mugs of strong tea and reported to the clothing store to be fitted for their uniforms. I gazed round in amazement - there must have been thousands of uniforms stacked in piles on benches and an ever increasing heap of discarded jackets, slacks and tunics outside the door of the changing rooms waiting to be sorted out, folded up and returned to their proper place on the shelves. The range of sizes was equally impressive. A girl would have to be a very peculiar shape indeed before London Transport would give up trying to supply her with a uniform from the stores. We learned that, should the occasion arise, her measurements would be taken and the necessary garments tailored to be delivered to Stores within ten days. We all disappeared into the changing rooms and then began a positive orgy of trying on jackets, divided skirts, slacks, overcoats and caps while the discarded heap outside grew higher and higher. Finally we all emerged triumphant wearing our new uniforms and looking very smart indeed.

When London Transport began recruiting woman conductors to cover call-up shortages in 1940 they decided to make a distinction between male and female staff and designed a uniform in grey worsted material piped with blue for all uniformed women staff on buses, trams and Underground services. The men wore navy serge uniforms - bus crews uniforms were piped in white - later, when male and female staff both wore navy blue, the bus piping became blue. Tram staff uniforms were piped in red and the Underground first in orange and then later in yellow piping.

We then filed over to the equipment bench to sign for a leather money bag, a long and a short ticket rack, a bell punch and canceller harness, a locker key, a turning handle to operated the indicator blinds, a small knife-shaped piece of metal which we later discovered was to clean out the ticket slot of the bell punch, a wooden board fitted with a bulldog clip to hold our waybills and a whistle on a chain.

Not having travelled on a tram since visiting my Gran as a child, I did not know that trams were classed as light railways and conductors were issued with whistles just like guards on trains. Some time between the wars bells were fitted on the lower decks but there progress ended and all the driver got as a signal to proceed was a shrill blast from the whistle when the conductor was on the upper deck. The war had already been going for two years and by now wrapping paper was a thing of the past. So all we got to take home our new possessions was several lengths of coarse string. We all decided to remain dressed in our uniforms, folding our new overcoats over our arms and carrying our civvies in a bundle tied with string.

We were then told to report to the conductor school at Camberwell Depot the following Monday and each issued with a temporary pass valid only between our homes and Camberwell and told to find or purchase a full face photograph one and a quarter inches square to be attached to our permanent stickies which we would receive on passing-out of the training school. Thirty-six years later, after dozens of changes of uniforms and staff passes, I still do not know just why these passes are known as stickies and I gave up asking years ago; but I can tell you this - the day I received my first permanent pass I felt as though I’d been handed the Freedom of the City. I knew that I could roam all over London, completely free, on trams, trolleys, buses and Underground trains and on the country services for a radius of more than twenty miles in all directions. Only the lordly Green Line Coaches were barred to us. They were regarded as the Elite Services and only the very high officials of the board were issued with passes for free travel on the Green Line Coaches, and no mere cardboard stickies for these gentlemen either - they carried silver medallions usually attached to equally impressive heavy watch-chains. Occasionally, though, they were shown in the middle of the owner’s palm and I can only guess at the fate of the conductor who, working in the blackout, took it from the owner thinking it was half a crown!

Contributed originally by 2nd Air Division Memorial Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jenny Christian of the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library in conjunction with BBC Radio Norfolk on behalf of Frank L Scott and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Part one

I was eighteen, going on nineteen, when the storm clouds of war started to gather. Life was good ; a happy home, loving and devoted parents and family, sound job prospects and a variety of interesting hobbies and out-door pursuits. All this adding up to an enjoyable and hopefully peaceful future. Life was indeed worth living!

My dreams were shattered on that morning in early September 1939 when the sirens sounded throughout the land warning 'Englanders' of an immediate air attack when the suspected might of the German Luftwaffe would rain down upon us.

Most people that could, and were able, ran for cover long before the mournful wail of the penetrating sound of the air-raid sirens had faded away.

My family consisting of Mother and Father, two sisters, three younger brothers and an elderly Grandfather took to our heels and made for the conveniently placed 'Anderson' shelter dug into the back garden. I can't remember the exact measurements of that particular type, but I do know that to house nine adults for any length of time, as it eventually did for several months to come, has to be experienced to be believed. Not only was it very uncomfortable in such a confined space but there was always a fear of the unknown horrors of bombing raids.

Within the shelter, there was the cheerful chatter to keep up our spirits but outside there was an uncanny silence which was broken some time later by the ALL CLEAR signal. A sound we got to love and hear. Nothing happened that particular day and we remained unscathed.

The sound of that very first warning at about 11 o'clock on Sunday 3rd September 1939 will long remain in the memories of many folk, the elderly and not so young, and was a discord we all learnt to live with and to rejoice endlessly to the welcome sound of the ALL CLEAR.

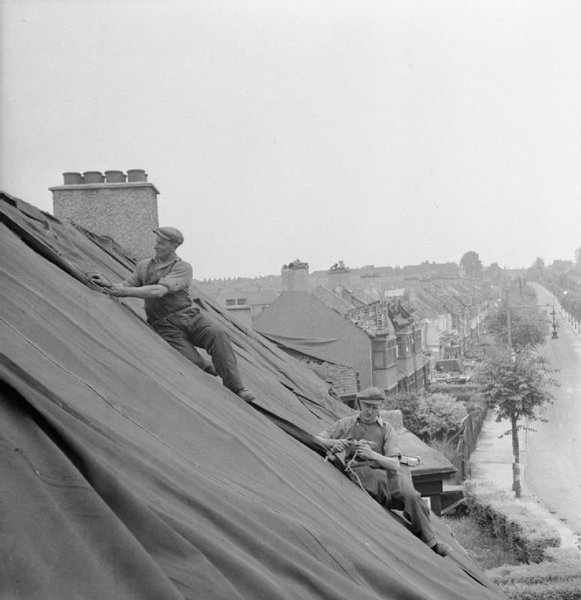

This situation continued for many months with warnings of imminent raids which came to nothing. So began the 'phoney war' as it became to be known. Because of the continuous interruptions caused daily when enemy aircraft were unable to penetrate the air defences, spotters were placed on rooftops of factories, offices, power stations etc., to warn workers only when there were signs of impending danger.

Unfortunately, this was rather short lived and many large towns and cities suffered badly when the German High Command decided to step up and concentrate on a more devastating and annihilating blow, in particular to the civilian population.

My personal experience of this period of time was when taking a girlfriend to a cinema in Elephant and Castle area of London and to be informed by the Manager of the cinema that a heavy bombing raid was taking place in the dock area of the East End. Not that that had much significance to a couple in the back row, who continued there until the bombing got worse and the Manager informed those remaining that the cinema was about to close.

Most people that were able to went underground that evening and it wasn't until the ALL CLEAR sounded in the early morning at daylight that they came out again and went about their business.

Living not far from this area, my first thoughts were for my family and I wished to check on their welfare as soon as possible. Because of the ferocity of the raid, there was much local damage and fires were raging everywhere, accounting for endless lengths of firemans' hosepipes to be trampled over in search of public transport which, by that time, was non-existent. Having escorted my girlfriend home which, unfortunately, was in the opposite direction to the one I would have wished to get me home quickly, but eventually I made it and found them safe and sound. A block of flats nearby had taken a direct hit during the raid.

This signalled the beginning of endless night after night bombing raids on London and 'Wailing Willie' would sound without fail at dusk about the time that mother would be putting the finishing touches to the picnic basket that the family trundled to the garden air-raid shelter. Not too often, but some nights for a change of scenery, or further company, we would go to a communal shelter but must admit that we all felt most secure at 'ours'.

So, life went on, come what may, raids or no raids. All went of to work the next morning trusting and hoping that our work place would still be there. Battered or not, running repairs would be performed and it would be 'business as usual'.

My father, being in the newspaper distribution trade and a night worker would clamber out of the shelter in the early hours but would return occasionally during the night to see that all was well. He would also drop in the morning papers which were often read beneath the glow of the searchlight beams raking the darkened sky in search of enemy aircraft. An additional item on one particular raid was when a nearby gasometer near the Oval cricket ground was hit and a whole cascade of aluminium flakes came drifting down in the light of the search light beams.

Being in 'Civvy Street' at that time, and in what was considered a reserved occupation with a company of manufacturing chemists, my only contact with the war and ongoing battles in various theatres of war was through the press. It was not until that little brown envelope appropriately marked O.H.M.S. fell through the letter-box did my involvement with the military begin.

"You will report" it began, and so I did to the local Labour exchange when it set the ball rolling with regard to medicals, which arm of the service, date of call up etc. I also remember that my company deducted my pay that day. Something I never forgave them for and therefore had no wish to rejoin them on release from the forces.

Came the day, or rather it very nearly didn't! One of the most frightening and devastating attacks on London came that night. The railway station that I had to report to for transport to camp had been put out of action and I can remember clearly seeing passenger carriages hanging onto the roads from railway bridges. Plan 'B' was immediately put into operation and road transport was made available to take us "rookies" to the next station down the line.

The Military Training Camp on the borders of Salisbury Plain became home for the next six weeks when one went through all the motions of becoming a fighting soldier, with discipline and turn-out being the Order of the Day. Whatever one says about Training Sergeants I think our Squad must have struck lucky because we decided to have a whip round and buy him a parting gift before our leaving camp and being drafted to a searchlight mob. Thus ended basic training in the Royal Artillery.

The next venue was over the border; a searchlight training camp on the West coast of Scotland. Within a very short time and very little action, boredom set in and a Regimental office notice calling for volunteers for Airborne Divisions prompted a few of my mates and I to put our names forward. Knowing the outcome of some of their eventual encounters in later battles I am thankful now that an earlier posting took me to a newly formed Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment of which I am justly proud.

Whilst serving with a searchlight Battery Headquarters in Suffolk, apart from the usual flak and hostile fire being an every day occurrence, Cupid's dart took a hand when the A.T.S. became part of the Establishment and a cute little red-head arrived on site. A war-time romance followed but a further posting from that unit took me to another part of the country. As the saying goes "Love will find a way" and it did for we kept in touch until distance and timing took its toll. That was over 50 years ago and through a twist of fate, a news item that appeared in a national newspaper put us in touch again.

My Regiment, the 165 H.A.A. Regt. R.A. with the fully mobile 3.7in gun had many different locations during the build up to D Day but it was fortunate enough to complete its full mobilisation for overseas service in a pleasant area on the outskirts of London. This suited me fine as it was but a short train journey to my home and providing there was no call to duty I would take the opportunity of going A.W.O.L. and dropping in on my folks for a chat and a pint at the local. However, I always made a point of getting back in time for reveille and no one was the wiser. It was also decided about that time that every man in the Regiment should be able to drive a vehicle before proceeding overseas so that was another means of getting up town for a period of time.

Inevitably all good things come to an end and we received our "Marching Orders" to proceed in convoy to the London Docks. The weather at that time was worsening putting all the best laid plans 'on hold'. Although restrictions as regards personnel movements were pretty tight some local leave was allowed. It would have been possible for me to see my folks just once more before heading into the unknown but having said my farewells earlier felt I just couldn't go through that again.

Part Two

With the enormous numbers of vehicles and military equipment arriving in the marshalling area and a continuous downpour of rain it wasn't long before we were living in a sea of mud and getting a foretaste of things to come.

To idle away the hours whilst awaiting to hear the shout "WE GO", time was spent playing cards (for the last remaining bits of English currency), much idle gossip, and I would suspect thinking about those we were leaving behind. God knows when, or if, we would be seeing them again. By now this island we were about to leave, with its incessant Luftwaffe bombing raids and the arrival of the 'Flying Bomb', had by now become a 'front line' and it was good to be thinking that we were now going to do something about it !!

All preparations were made for the 'off'. Pay Parade and an issue of 200 French francs (invasion style), and then to 'Fall In' again for an issue of the 24hr ration pack (army style), vomit bags and a Mae West (American style). Just time to write a quick farewell letter home before boarding a troopship.

Very soon it was 'anchors away' and I think I must have dozed off about that point for I awoke to find we were hugging the English coast and were about to change course off the Isle of Wight where we joined the great armada of ships of all shapes and sizes.

It wasn't too long before the coastline of the French coast became visible, although I did keep looking over my shoulder for the last glimpse of my homeland. The whole sea-scape by now being filled with an endless procession of vessels carrying their cargos of fighting men, the artillery, tanks, plus all the other essentials to feed the hungry war machine.

The exact role of my particular arm of the Royal Artillery was for the Ack-Ack protection of air-fields and consisted of Headquarters and three Batteries, each Battery having two Troops of four 3.7in guns, totalling some 24 guns in all. This role was to change dramatically as we were soon to discover. In the Order of Battle we would not therefore be called into action until a foothold had been successfully gained and position firmly held in NORMANDY.

The first night at sea was spent laying just off the coast at Arromanches (Gold Beach) where some enemy air activity was experienced and a ship moored alongside unfortunately got a H.E. bomb in its hold. Orders came through to disembark and unloading continued until darkness fell. An exercise that had no doubt been overlooked and therefore not covered during previous years of intensive training was actually climbing down the side of a high-sided troopship in order to get aboard, in my case, and American LCT.

This accomplished safely, with every possible chance of falling between both vessels tossing in a heaving sea, there followed a warm "Welcome Aboard" from a young cheerful freshfaced, gum chewing, cigar smoking Yank. I believe I sensed the smell of coffee and do'nuts!!

Making sure that the assigned vehicle for my entry into Normandy and beyond was loaded aboard I settled down, anticipating WHAT, but surveying the panoramic view as we approached the sandy shore by now littered with the remains of the earlier major onslaught.

Undoubtedly one couldn't have been too aware of the incoming and outgoing tides as the water was far too deep at the beach-head and found it necessary to cruise around until late into the evening before it was decided to make for the shore come what may!! By then it was time to join the other members of the regiment's advance party in the Humber staff car which included driver, a radio operator, the C.O. and Adjutant.

Following the dropping of the anchor, the loading ramp was immediately lowered to the accompaniment of the sound of the engines breaking into life. I think at that point the two officers became aware that we were still in 'deep water' for they decided to climb onto to roof of the 'Z' vehicle as it proceeded down the ramp. In spite of seeing the sea water gradually climbing half way up the windscreen the O.Rs feet remained reasonably dry and we made the shore with the aid of the four-wheel drive.

At the first peaceful opportunity it was essential to shed the vehicle of its waterproofing materials and extend the exhaust pipe. The canvas parts of this exercise I decided to keep, as I thought that they would be useful (time permitting) for lining ones fox-hole, which I later found to be ideal.

My ancient tatty looking 1944 diary informs me that I slept in a field and awoke at 05.30hrs to a glorious sunny day, that I washed in a stream,sampled my 24hr ration pack, saw my first dead jerry and that General De Gaulle passed the Assembly Point.

I must admit that without the aid of my diary that I managed to keep throughout the war (something that I could have been very severely reprimanded for had it been known at the time) and the treasured letters that my Mother retained until her dying day, I could not possibly remember all the most intimate details of my soldiering days.

Returning to those early entries, whilst enjoying the pleasure of a quick splash in a neighbouring stream I became aware of some girlish giggling in the adjoining bushes and felt that this was an early indication that the natives were friendly.

We proceeded inland, the Sappers having done their stuff and prepared safe lanes amid endless rows of tape with the deathly skull and crossbones indicating ACHTUNG MINEN, it was decided to set up Regimental H.Q. in the area of Beny-sur-mer.

During a check halt en route I noticed that a small area of corn a few yards into a vast cornfield had been disturbed. Taking a chance and feeling inquisitive I decided to investigate. And there it was the ENEMY, but proved not to be too much of a problem. How long he had been there I do not know. He was lying on his back, his feet heavily bandaged no doubt through endless marching, his Jack Boots placed beside his body. I also notice hurriedly that his ring finger was missing? Someone's Son, someone's Father, someone's brother, someone's liebe; what a ghastly business war is !!

It occurred to me that all my observations of German manhood from the then current movies and other sources gave one the impression that they were a somewhat super human race; six foot tall, blonde and blue-eyed. That is what the Fuhrer had aspired to no doubt but I was rather taken aback to see the first column of German prisoners passing by, some short, fat, bald, spectacled etc. etc. a straggly pathetic bunch, tired, weary but some still with that aggressive look in their eyes, some glad that at least the war and the fighting were over for them.

Several moves to different locations were made in the ensuing weeks, also being 2nd Army troops, we were at the beck and call of any Corps or AGRA needing support and CAEN had to be taken at all cost.

Being on H.Q. staff one of my 'in the field' roles was to travel with the Staff car into the forward areas and reconnoitre sites prior to the deployment of the heavy artillery. Here I would remain until the last of the units had passed through that check-point with the expectation of being picked up sometime later when the whole procedure would continue again with a type of leap-frogging action.

Following days of constant heavy shelling and later to watch a 1000 bomber raid from the outskirts of that well defended town of Caen it finally fell. Having dug ourselves in and around an orchard in the Giberville area, east of Caen, some late evening mortar fire sadly killed our Second-in-Command (Major Finch) when the shell struck an apple tree under which the officers were playing a game of cards. Here again my diary notes "heavily shelled at 22.00hrs. 2nd i/c killed, Lt. Quartermaster, Padre and Signals Officer wounded." The following day we buried the 2nd i/c and felt the terrific loss to the Regiment. Several years later through the very good services of the War Graves Commission I was able to trace and eventually visit his grave lying in peace in Bayeux cemetery.

Passing through the ruined and by now almost deserted corridor in Caen I stopped to retrieve a slightly charred but intact wall plate bearing the towns name from the still burning rubble. Somehow it had survived the crushing bombardment and would now protect it as a war souvenir. This memento I eventually carried through France, Belgium into Holland and on to the borders of Germany. Here I was lucky in a draw for U.K. leave and returned home to family bringing the wall plate for safe keeping where it continued to survive the continuing London blitz.

Sadly several years later, and happily married, my wife during a dusting session knocked it from its focal point and it broke into several pieces. I could have wept, remembering its passage through time but my good sense of humour saw the funny side of it all. Having put it together again it does have the appearance of having 'been through the wars' but still has a place of honour on my kitchen wall. Have thought over the years that I should perhaps return it to its rightful owner, but just where does one start?

Returning to the ongoing war in Europe it appeared that things were going as well as could be expected on all fronts. There were occasions when having dug a comfortable hole in the ground word would come through "we're moving again". There were no complaints as such if it was felt it brought the end of hostilities a little closer. It became a bit tough when this could happen sometimes three times in one day and with the approach of winter the earth was getting harder all the time.

It was comforting, however, to hear that the Germans were retreating down the Vire-flers road. Again my old diary reveals the path taken by the Regiment from landing in Normandy through the Altegamme on the North bank of the river Elbe, Hamburg. It gives dates and places and highlights the fact that we were forever crossing borders e.g. France into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland back into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland into Germany where we remained.

Its mobility can perhaps be made clearer in an extract from the Regtl. Citation which quotes

"The unit has been deployed almost continuously in the forward areas, and the Headquarters and Batteries have frequently been under shell and mortar fire. During this time the Regiment has not only fought in an A.A. role but has been detailed to other tasks not normally the lot of an A.A. unit. These have included frequent employment in a medium artillery role, action in an anti-tank screen, and the hasty organisation of A.A. personnel into infantry sub-units to repel enemy counter-attacks. All tasks have met with conspicuous success. The unit has responded speedily, cheerfully and efficiently to every demand made on it. The unit is one where morale is very high indeed and which can confidently be given any task".

Following the distinctive role played during the N.W. Europe campaign the Regiment was awarded a Battle Honour and its Commanding Officer a D.S.O.

Depending on the impending battle plan the various Batteries would be assigned to individual tasks i.e.

275/165 Bty u/c Gds. Armd. Div. for grd. shooting.

198/165 Bty deployed in A.A. role def. conc. area.

317/165 Bty deployed in Anti-tank role.

All tasks having been successfully completed would again move as a Regiment under command Guards Armoured Division to support a new attack.

A day to be remembered was the arrival of bread after some 40 days without. I think it only amounted to one slice per man but what a relief after nibbling on hard biscuits for so long. The men to be pitied were those with dentures who automatically soaked it in their tea or cocoa (gunfire) before consuming.

Another welcome treat was the arrival of the mobile bath and clothing unit in late August '44. It was about that time that I heard a steam whistle indicating that the railroad was back in action.

When the situation allowed a truck would take a party of men to the nearest B and C Unit which consisted of a couple of large marquee tents adjoining. In one you would completely disrobe and proceed along duck-boards to the shower area. Having enjoyed this primitive delight and dried off you would then gather vest, pants, shirt and sox then queue to be sized up by the detailed attendant in charge, to be issued with hopefully something appropriate to ones stature. It didn't always work to ones liking and caused much amusement in the changing tent where swaps occasionally took place.

The unit did however serve its purpose at the time but things became more pleasant when one could retain their own gear and could sometimes get it attended to by a local admirer.

Four moves in as many days took us into Brussels where we were given a rousing reception. Our vehicles were clambered onto from all directions by the thronging crowd, showering us with hugs and kisses, flowers, and a very brief moment to sample a glass or two or wine. No time to stop, unfortunately, and soon to depart with a small recce party en route for Nijmegan. By now things were getting slightly uncomfortable having been attacked from the air during a night in the woods and the main body of the Regiment attacked in the corridor at Veghel.

Here our guns were deployed in an Anti/tank role, field role and CB role. Several troops were provided for attack to recapture the village of Apenhoff. A tiger tank was engaged by one gun and very successful CB and concentrations fired on enemy gun areas and infantry. It was thought that casualties sustained were justified as the attack resulted in the capture of 76 prisoners, one anti-tank gun and a considerable number of enemy dead, mostly to the West of the village where most of our men finished up and where a certain amount of mortar fire was brought down upon them.

The following day the main body of the Regiment arrived in Nijmegan and were deployed in an Ack-Ack role, minus one Troop still in MTB role. It was recorded at the time that on several occasions the guns had been deployed further forward than any other guns in the Second Army and in the case of the bridge over the Escaut Canal at Overpelt it was considered that the fire provided was one of the chief factors in the bridge being captured intact.

It was during a return to Belgium for a break just before Christmas 1944 that we had the good fortune to be billeted for a few days with a wonderful family consisting of Mother and Father, six daughters and two sons. The childrens' ages ranging between possibly eighteen and three. It was the time of celebrating St. Nicholas and homely pleasures had long been forgotten as regards a roof overhead, surrounding walls, and to mix with warm and friendly people. The chance to sit at a dining table on a firm and comfortable chair, food on a plate instead of a dirty old mess-tin were simple things to be appreciated beyond words and all were saddened when it was time to return into the line.

A returning Don, R would often bring little notes written in understandable English but as the lines of communication lengthened so contact diminished.

Some 40 years later, prior to a visit to The Netherlands with a party of Normandy Veterans, I decided to write to the Burgomeister of the small village of Beverst giving him full details of the family and hoping by chance that at least one member of the large family would have survived the war and perhaps was still living in the Limburg area of Belgium.

It was beyond belief that within ten days I had a letter from the very girl, Mariette, who had sent the odd letter to me and to this day still have them in my possession. We had so much to tell each other, on her side that all her sisters were married with children, and that one of her brothers who was three years old during the war was now a priest in Louvain.

As the conducted tour at the time of visiting did not go into the Limburg area of Belgium, it was arranged that a small party from the family circle would travel by minibus and that we would hopefully meet up at a suggested time in the town of Eindhoven in Holland. There was much rejoicing when the timing was spot on and a very brief meeting with an exchange of gifts took place before it was time to clamber back onto the coach.

Over the years when visiting the Continent we meet whenever possible. I have since met all surviving members of the family, visiting their homes and meeting their children. At one of the locations a field a short distance away was pointed out to me where Hitler, a Corporal at the time, had camped during the 1914-18 war.

During one conversation I asked Mariette how the family had fared during the German occupation. She told me that on one occasion a German Officer had knocked on the door requesting the family to accommodate some German troops. The Father replied that he had eight children which he was supporting and had no room for them and luckily they departed. She went on the tell me that when the Germans were pushed out of the village and the English and the Americans moved into the area her Father gladly accepted a few English soldiers to stay, suggesting the family would double up into a couple of rooms. We still find plenty to talk about over the years when corresponding and on meeting up.

In further praise of my old Regiment it is on record that before June '44 was out, a deputation of senior officers visited the unit to learn why, and how, they were usually the first guns in the line to report "READY" and higher formations were calling for their support as a unit.

The Order of March for the operation "Garden", the Northward dash to join up with the Airborne troop was headed (1) Guards Armoured Division, (2) A.A. Group (165 H.A.A. Regt.) leading. This alone should rank a citation for the 3.7in A.A. gun. Second in the Order of March on what must be one of the most daring and spectacular assaults in history.

The 3.7s when used in their field role were fired from positions amongst the infantry and that having no gun shield the layers positions were untenable. During the closing battle for Arnhem they were able to give covering fire throughout the night withdrawal. The 3.7s with their 11 miles range were amongst the very few guns available with sufficient range to cover the flanks of the 1st Airborne at Arnhem, and for a long time there was talk of the unit being permitted to carry the honoured Pegasus on their sleeve.

It was during the withdrawal of the survivors of the Battle of Arnhem, and watching the war-torn paras filing back through Hell's Highway, that I spotted and had a quick chat with a couple of my old mates that had proudly volunteered with me on that fateful day in June '41. In a flash I though "there, but for the grace of God go I". Should I have in fact survived that horrendous and tragic battle, and where are they now I wonder?

Word that hostilities had ceased came through whilst in a little German village called Tesperhude on the North bank of the Elbe, V.E. DAY, the war in Europe had ended. Time to celebrate. All Other Ranks were invited into the Officer's mess where 'issue rum' was being served up in half-pint glasses. This was a complete change to previous issues when, during inclement weather the rum ration would have to be taken in a mug of tea. Pushing all protocol aside it was time to let our hair down and enjoy. It was suggested that a bit of music and song would be in order and the question was asked as to who could play a piano accordion. I gave up the idea of not volunteering on this special occasion and said that I could, having had some professional lessons in my youth.

A search party set off down the street and a 'squeeze box' was produced and promptly placed in position. By then the rum was taking hold and I can remember getting through two verses of "Home on the range" before collapsing over backwards to a cacophony of sound as the bellows extended across my chest. Can't say the C.O. and other Officers were too pleased with the musical performance and I felt the effects of the vapours for a few days following. I made up my mind there and then that I never wished to experience the taste of Nelson's blood ever again, as I also felt about the thought of never wishing to see spam and bully beef, but time is a great healer?

Release from the service being on an 'Age and Service' basis meant that I possibly had another year or so to serve before being discharged. I would have been more than content to remain in the area of Hamburg until my release papers arrived, but unfortunately it was not to be. An urgent War Office posting, I was told, brought me back to England and a spell at Woolwich Barracks which I found most discouraging and ungratifying.

I was to join a newly formed contingent of mostly new recruits about to depart for the Far East, by mid November '45 I was on a troopship bound for Bombay. Christmas 1945 was spent in the Royal Artillery Transit Camp at Deolali where I spent a few weeks before entraining and travelling across India to Calcutta. It wasn't quite the Orient Express for comfort and cuisine, and I can remember being fired upon by rampaging dacoits at one point.

Several more weeks were spent in a transit camp in Calcutta experiencing all the delights of Chowringee and thereabouts – felt quite the pukka sahib at times before word came through that we would be sailing for Rangoon the following day.

Going aboard the S.S 'City of Canterbury' there was the usual rush for hammocks and best positions on deck. Arriving in Rangoon I was happy to receive my first letter from home in seven weeks and was a relief to be sure. I had still not reached journeys end and it was not until mid February 1946 that I joined my intended unit, a Field Regiment, on the borders of Mandalay in Burma.

I was finally homeward bound by the late summer of '46 to enjoy three months overseas leave and a return to civilian life.

Looking back over the years in the forces there were some good times and some exceedingly bad times but having come through it all reasonably fit and healthy I feel the WAR YEARS have shown me the true value of life and that, in retrospect, I feel proud not to have missed this experience of a lifetime.

Written in March 1994.