High Explosive Bomb at Mayall Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: Aggregate Night Time Bomb Census 7th October 1940 to 6 June 1941

Fell between Oct. 7, 1940 and June 6, 1941

Present-day address

Mayall Road, Stockwell, London Borough of Lambeth, SW2 1AS, London

Further details

56 18 NE - comment:

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

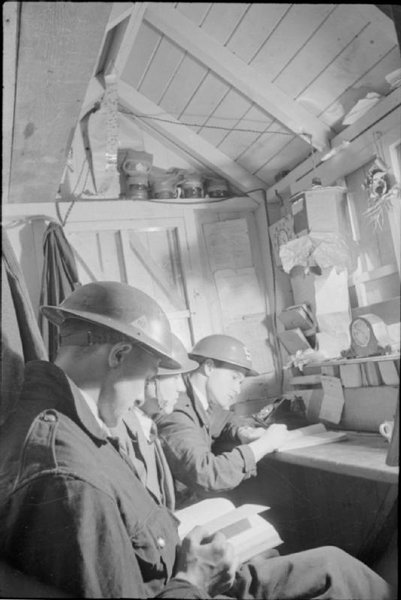

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by jogamble (BBC WW2 People's War)

My Grandfather was Flight Lieutenant Leonard Thomas Mersh and this is just a glimpse in his life during World War 2, like many of the pilots he has a number of log books, with many miles accounted for and the stories to go with them.

Len went to Woods Road School in Peckham and then on to Brixton School of Building, where he qualified as a joiner. In 1938 at 18 he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve. At Aberystwyth he made the grade to be a pilot and was then sent to Canada for further training in Montreal and Nova Scotia Newfoundland where he gained his wings on Havards and Ansons.

Once back in England he went to Aston Downs and flew many aircraft across England, eventually he was posted to East Kirby in Norfolk attached to 57 Squadron Bomber Command. He flew many missions over Germany and France and as far as the Baltic. Missions included laying mines in the fjords where submarines and battleships where hidden. Dresden; Droitwich, Hamberg, Nuremberg, Brunswick and Gravenhorst were some of the places he bombed. Some times he carried the Grand Slam bomb.

In January 1945 he and his crew where sent to Stettin Harbour to lay mines at night. They where one of the lucky ones, as 350 planes had been sent and only 50 came back. Granddad’s plane was attacked by enemy fighters and was hit but they managed a second run over the target to release their mines.

In March 1945 during a sortie against Bohlen, his aircraft was attacked by a Junkers 88. The plane was hit but they made three bombing runs and then hedgehopped back to England.

On the 26th October 1945 Leonard was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, (DFS), for courage, determination and efficiency.

After completing operational tours and six mine laying sorties he was drafted to 31 Squadron, Transport Command at the end of the Dutch Indonesian Campaign flying VIPs. He flew General Mansergh to Bali being the first RAF plane to land on March 8th 1945 to accept the Japanese surrender.

In 1948 Leonard was drafted to Germany to help with the Berlin Airlift. The squadron reopened airstrips which had been closed at the end of the war, plot routes into Berlin and get them working, the Americans would move in and the squadron would move on to another station. They flew by day and night and were lucky to gain 5hours sleep, which was taken in Mess chairs, which is perhaps why he caught TB, which ended his career and he then spent a lot of time in and out of hospital.

Contributed originally by JackCourt (BBC WW2 People's War)

Memories of growing up in the London blitz

During the doodlebugs raids, I was Winston Churchill Sunday paperboy.

On one Sunday morning I had knocked on the door of No 10, the door opened. I was just about to hand over the papers when a flying bomb engine cut out. Now this could have meant a lot of things one of which was it coming straight down. The attendant threw the papers in the hall and shut the door, with me inside no.10. Well only just. There was a muffled bang, which meant the bomb was about a mile or so away. In one movement the attendant opened the door had me by the collar then threw me out with a ‘Now f**k off out of No.10’.

So my invitation into a tiny part of the corridors of power was ignominiously short lived.

Another time much about the same period doing the same paper round I had just delivered papers to a big house off Hyde Park corner, opposite the old Bell grave hospital. Again a doodlebug cut out. I dived off my bike into the gutter straight into a dip puddle. I lie there with my hands over my head, elbows over my ears.

After about couple of minutes I could hear laughter. I looked up where three nurses were leaning out of a window, who thought I was funnier than the Marx Brothers. I got up, the front of me soaked. This caused even greater laughter. I got back on my bike peddled over Vauxhall Bridge toward the Oval cricket ground. Yet another flying bomb cut out. I’m not getting off this time to make an idiot of my self the next thing I knew I was peddling with no ground be nigh me. Next the bike hit the ground I came off in a heap but I was all right. When I got to the Oval it was a dreadful scene. Archbishop Tennyson School, which was being used as an Auxiliary Fire Service station had a direct hit. There were many bodies. Much too bad to try to describe The A.F.S were considered a joke at the beginning of the blitz, but not at the end. They were some of the bravest men and women in a time of a lot of brave men and women!

My mother, Nora, was the bravest person I ever met. Lots of people were afraid in the London blitz but my mum was truly terrified in spite of the fear she never and I mean never let it interfere with the ordinary things she had to do she went work, war work which meant her being away from home for at least two days and nights.

There were quite a few examples of her near schizophrenic attitude to the blitz but the best, I think, was the night we both went to see a film called ‘THE RAINS CAME’ Nora loved going to the pictures.

We got into the Odeon; at Camberwell Green about 5pm saw the first feature then the main picture came on about 6.30.

Now while the ‘The Rains came’ was in black and white it was a big picture, good music and loud. Half way through the film the familiar side came over the picture that the siren had sounded and any one wishing to leave could do so and come back for any other performance, if they held on to their ticket. Mum started to get up to go. I persuaded her to stay, until the very loud earthquake scene.

She dragged me out of my seat saying she thought the cinema was about collapse. When we got out into Cold harbour Lane there was quite a lot going on. The ack-ack was trying to hit the planes and the planes were dropping bombs, luckily not close to us but the shrapnel from the guns was pinging away every where. We sheltered in the Odeon exit door way. In spite of all the chaos that was going on an old 34 tram came chugging up from Camberwell Green. Out ran mum waved down the tram, the driver slowed down enough for us both to get on. We got of at Loughbough junction. As soon as she was off, Nora started to run towards our flats, down Loughbough Road,

There was no way I could keep up with her. When I got to the door of our flat the door was open. I called out to her ‘I’m under here’ She was under a very small kitchen table. Nora felt safe. Rodger Bannister was supposed to have done the 4 minute mile in the fifties, I reckon my mum did it in 1943!

The next memory is a maybe, only a maybe be cause, at times; I can hardly believe it happened.

One dark and cold Sunday morning on my celebrity paper round I had handed in Winston Churchill’s papers at No. Ten and was coming down the stone steps of the Foreign Office, Anthony Eden’s papers, the Foreign Secretary at the time.

I was half whistling half singing and doing a dance down the steps, a song and dance I had seen in a film the afternoon before at the Astoria Brixton. I got on my bike about to ride off when a loud voice shouted’ Stop that infernal row’ I shouted back ‘ You can shut your bleeding ears cant you’ and rode quickly off.

About twenty years later I was in a pub in north London I was telling that tale when an unknown, to me, looked at me and said ‘You lying toe rag’ the bloke accused me of reading a book, he had just read by, Churchill in which he said an errant boy had once told to shut his ears. For all my insistence of innocence the bloke turned nasty, so I never got to find out the name of the book. I got a black eye though.

I swear that it happened. Not that anyone will believe me!

My father has not featured so far because he was in the army.

I think the only funny thing I remember, I’m sure there were others but I can’t remember, was the night before he left to join his unit.

It was a time of a lull in the air raids. I was just going to bed in our flat. My dad told me to sit opposite him. I was expecting him to tell me to be a good lad and look after mum. No!

The whole of the paternal side of my family, men and women were avid Arsenal football club supporters had been since the club arrived in North London, an uncle had actually been a shareholder!

He started: “ You know that Highbury has been bombed and the ‘Gunners’ now have to play all their games at White Hart Lane, (Tottenham Hotspurs ground) now I don’t want you going over to Spurs more than twice a season, home and away, it wouldn’t be right.” He gave me a hug. “ Off you go to bed, you’ll get a good nights sleep to night”. In the morning he was gone

Next memory One has to remember that even in the doodlebug raids very few ever got more than four hours sleep a night, I wonder now how any body kept up, with going to work at 8oc doing eight hours work then starting the whole thing over again and having a good time in between. On the night in question I was down the shelter with my mum and a good mate Ken, he slept in the bunk above me. We had taken to going down the shelter again, it was the start of the flying bombs and it was a bit dangerous up above at night. It didn’t seem to matter so much during the day.

The usual banging could be heard in the shelter but I was tired and went to sleep. A loud bang woke me also Ken. “ That was a close one, lets go and have a look”. It must have been after 3am. “Na I got to be at work early tomorrow, I’ll leave it”. Ken went off to explore. After a couple of minute’s I started to smell moved earth, earth that had not been moved in a long time, even down the shelter you could smell it.

I got up, went out to look for Ken. I went towards Loughbough junction, half way up Loughbough Road I heard singing. It was Ken pulling half a doodlebug out of the fair size hole, it was still warm. “This beats the usual bit of shrapnel” We managed to get it up to Ken’s balcony, outside his flat. When Kens mother came up from the shelter and saw half a flying bomb. She told Ken in no uncertain manner to get ride of it. Which to Kens great regret we did. We put it in Loughbough Road outside the flats where it soon disappeared.

Finally these are quotes from a great Lambeth Walk personality called John Shannon a truly funny man I could go on for an hour with his stories, he has a son also called John Shannon who became a very successful TV actor. I hope the younger John doesn’t mind my telling just two of John senior tales.

On September 3rd 1939 when the first siren of the war sounded at about 11.15. that Sunday morning. John shouted to his wife “The sirens have just sounded, come on”. She shouted back “I cant find me teeth”. To which John shouted back “There going to drop bombs not ham sandwiches”!

After, they ran to Lambeth North tube station for shelter. John told me he had his gas mark on.” I had to take it of Monday after noon”. Foolishly I ask why? John said, “I was hungry”!!!!

===========

My best mate's in my growing up were Ken Power and George Gear. We shared a massive amount of good times, and not many bad ones.

There were four blocks on the Loughbough estate; sixty flats in each block, with an average of two kids a flat! About 500 boys and girls.

I hope I have captured, into the story, the 39-45 feeling, London had at the

time. It was a very special emotion.

There was one instance that may give an insight into ordinary attitudes of the time. This true happening is not meant to show me as an exceptional human being. Any one else would have done the same, which is the point I am trying to make. I was fifteen in 1944. I worked Monday to Friday, 8am to 6 p.m., Saturday's 8am to 12.30 p.m. for which I received 18/6d a week. On Sunday mornings, at 4.am I did what was known as W.H.Smiths Roll-ups, Sunday papers for the famous. I was the Prime Minister's Sunday morning paperboy. The Right Honourable Winston Churchill together with, Anthony Eden,

Lord Beeverbrook, AV Alexander, Lord Halifax and many others. I do not write this to show off...............,well maybe a bit, but to say that I got the unbelievable amount of 25/6 for just the Sunday morning, which was collected before starting our rounds, and the whole round only took one and a half hours.

Bear with me, please.

On Sunday morning the 28th of May 1944, I turned off Whitehall into Downing Street to deliver the last of the papers, to the Foreign Office and Mr. Churchill. In those days there was a sandbagged barricade, manned by the brigade of guards, at the entrance to Downing Street. Whenever I cycled into Downing Street in the dark there was always a cry of 'HALT WHO GOES THERE'. I would slow the bike down and shout back, 'PAPER BOY ' then there was a 'PASS PAPER BOY.' The barrier was lifted and into the street I rode.

On that morning in May, the papers delivered, I started to cycle home. I went to cross Westminster Bridge. It was about 5.30, just beginning to get light. As I passed the wonderful statute of BOADICEA in her chariot, I saw a solider, an American soldier, standing on top of a parapet looking down at the water, his tunic was undone, flapping in the wind, he didn't look much older than me, about nineteen.

I got off my bike to lean it against the bridge.

"What you doing up there?" I asked. The Yank, a sergeant, gave me an obscure, vague look.

"Why don't you f**k off kid, cant you see I'm busy."

"I can see you are going to fall into old father Thames, if you don't watch it. " I replied.

To slice a very extended tale, it turned out he had lost all his money in a crap game, at the time I did wonder what any one would be doing playing with shit for money, any way he was skint, also he was AWOL, absent with out leave, I didn't know what it meant at the time either, but more importantly he was scared, scared about the coming invasion into Europe, which he would be a part of.

He thought he might let his mates down. We had a talk.

He asked me about the blitz and was I in it? Well, after a bit he perked up. He said he would go back ' To his outfit '. I gave him 10/- for the fare to Portsmouth, out of my mornings wages. It never occurred or mattered to either of us how I was to get my 10 bob back. It was like that in the war, you always thought, it could be someone you loved in trouble. My Dad was in the army at the time.

I thought about the American sergeant when I heard of the invasion on the wireless.

I have always hoped that Yank, I didn't even know his name, made it through the war.

The invasion he was worried about took place nine days after our meeting.

I don't know if that story helps to explain the superlative feeling of togetherness we had at the time. I hope so!

I was 10 and a bit on 3rd September 1939, I would be 11 in November,.

I had been evacuated to Hove, near Brighton a few weeks before.

Kevin McCarthy and I were walking along, what we thought was, a disused railway line when the air-raid siren sounded, we knew what it was for they had been practicing that dreadful sound for months in London. An unknown man shouted to us to get off home as WAR had been declared. The woman with him started to scream, loud.” There coming, they’re coming” she went on.

“Shut up you silly cow” The man slapped her face.

“Who’s coming?” I shouted.

“Stop taking the piss and f**k off back home”

“What all the way to Brixton” laughed Kev then added “Bollocks”

The man started to move towards us. We started to run stopping every so often to give him two fingers.

He threw a big stick, which hit Kev on his head. We got off the rail track just in time for a steam train to pass us.

Kevin had blood coming from his head, so I reckon I was present

at the first casualty of the Second World War.

I got back to London just in time for the start of the blitz, Saturday the seventh of September1940, about tea time, been a glorious day.

We really didn’t know what hit us. There were hundreds of planes. The barrage balloons didn’t seem to make any difference. From memory that first raid seemed to go on for about twelve hours. South London wasn’t so bad but East London got it very bad.

I don’t think us kids knew what a great time we were going to have. I know that sounds daft and insensitive to all the families who had love ones killed and injured. But for some kids of my age it was a freedom and ‘not give a shit time’ we never could have imagined, those boring, able to do nothing Sundays, had ended.

It became an every day a new adventure, school became a joke, half a day afternoons one week, mornings the next.

So a few memories, it was a long time ago so dates and times could be a bit out.

One Saturday, early evening I had been to Brixton market with my Mum, shopping, for a reason I cant remember Nora, my Mum, was carrying a neighbour’s small baby, who in latter life became ballet dancer at Covent Garden, I had the shopping. The sirens sounded, funny but that sound could turn my stomach more that the actual bombs.

We heard the sounds of the planes then the ack-ack guns that most have been on the railway line at Loughborough Junction, cause they were loud. We started to run towards our flats and a shelter. We got to the first block and dashed in the nearest porch we came to. Sheltering there was an air-raid warden in his tin hat. By now the noise was immense. It was always a great sock to anyone experiencing the blitz for the first time, the great, great, noise, the never before heard of sounds, the echoes that hurt the chest.

Once in the porch the warden shouted to Nora “Give us the baby I’ll hold it for you, you look all in” And with all that was going on Nora Shouted back “No that’s all right you got glasses on if he wakes up you might frighten him” Only Nora!

Contributed originally by gloinf (BBC WW2 People's War)

Since forming the Evacuees Reunion Association many people have asked for an

-Account of my own evacuation and why I founded the Association.

What follows is an attempt to meet that demand.

1938 and the war clouds are forming.

I was seven years old in 1938, living with my parents, three brothers and sister in a five bed roomed house in Camberwell, south London.

As the youngest of the family I lived a very sheltered life, there was always someone there to look after me. Our way of life was strictly governed by the social rules of the time and of our immediate environment.

To understand those rules you need to know the history of Camberwell from when it ceased to be a rural village in the County of Surrey and first became a very fashionable suburb of London, later .to find parts of the area degenerate into crowded slums.

The Victorian houses in our road ceased to be lived in by people who could afford to employ servants but it remained quiet and very ‘respectable’.

On Sunday mornings we children would go for walks to places such as Ruskin Park, but before we were allowed to set off we had to line up and be inspected by our father, who would look to see that our shoes were highly polished, our hair brushed and combed and that we boys’ ties were straight. “No child of mine leaves this house looking scruffy!” was his rule.

We were only allowed to go to the park and there were certain parts of Camberwell and Peckham that we were forbidden to walk through, sometimes, we broke that rule, only to be shouted at by the children who lived there. Such was the social structure of the times and the district.

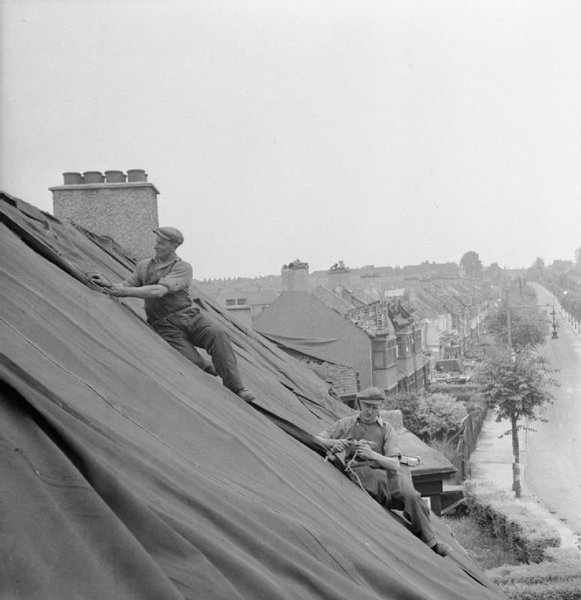

During 1938 and early 1939 we saw the preparations for war being made, sandbags were stacked in front of public buildings, gas masks were issued and great silver barrage balloons wallowed in the sky over London.

The Anderson shelters were made available for people with gardens and parents were urged to register their children for evacuation. My parents attended the meetings at o schools and decided that we should go if war broke out.

As I was only eight and brother John nine, it was arranged that we would not be evacuated with our own school but with that of our sister Jean who was then nearly fourteen. Brother Ernest was to go away with his own school, but our eldest brother, Edward, had already left school and therefore stayed at home until being called up for military service.

During the summer holidays of 1939 the order came that schools in the evacuation areas were to immediately reopen and all children who had been registered for evacuation were to report daily to the school they were to go away with, taking with them the things parents had been told to pack, plus enough food for a day, but nothing else.

No one knew when, or even if, the evacuation would begin. Everyone involved had to wait for the government to issue the signal ‘Evacuate Forthwith’, which happened on Thursday 3l August 1939.

Evacuation Day

When I went to my sister’s school on the morning of Friday 1 September, with my gas mask in its cardboard box slung over one shoulder and carrying a little suitcase, I didn’t know what was about to happen. Soon we were lined up in a long ‘crocodile’ and the teachers came round tying luggage labels on us.

Then, led by the Head Teacher and two of the bigger girls carrying a banner on which were the words ‘Peckham Central Girls School’, we marched out on our way to a railway station, with a policeman in front to stop the traffic.

We didn’t know where we were going; neither did our parents or most of the teachers. All that was strictly a secret.

I can remember every detail of that day, the crowds of parents standing in silence on the other side of the road — they were not allowed to walk with us — I wondered why so many of the women were crying and why a very angry man was shouting “Look at those luggage labels, they are treating them like parcels!!!” I was wildly excited, after all my parents had told me I had nothing to worry about, it would be like going on holiday and that we would all be home again before Christmas.

Little did I know that four years would pass before I returned home for good, or that our very close family would never again be fully reunited.

I caught a glimpse of our mother in the watching crowd and waved to her, but I don’t think she could see me. I often think what it must have been like for her to return home knowing that four of her children had been taken away, to where she didn’t know, and to see four empty chairs at every mealtime and four unslept beds. How quiet the house must have been.

They marched us to Queens Road, Peckham, station. To reach the platform you had to climb a steep flight of wooden stairs and on the way up some of the girls stumbled, causing others to fall on top of them. The platform was already crowded as another school was already there.

That was when the teachers and porters started shouting “Keep back, keep back” and pushing us away from the edge of the platform. But there was no room at the back.

After a long wait a special train arrived and a mad scramble aboard began, brothers, sisters and friends trying desperately to keep together, teachers trying to push us all into the tiny compartments.

Then the porters ran along locking the doors. It was old fashioned, non-corridor train and therefore had no toilet facilities, the day was hot, the journey lasted hours and the results were inevitable.

Eventually the train stopped at a country station and the staff came to unlock the doors. Then all the shouting started again as they hurried us off the station, but first we each had to collect a carrier bag containing foodstuffs that were to be given to the people who took us in.

In each bag was also a big bar of chocolate.

Soon there were hundreds of children milling around the station forecourt, with their teachers frantically trying to keep them together.

A solution to the problem was quickly found — they put us in the pens of the adjoining cattle market, where we waited to be taken by bus to the village school.

I only saw one single deck bus that ran a shuttle service, so for so the wait was a long one. Someone found a working standpipe in the cattle market to we were all drinking from that.

Eventually we arrived at the tiny village school, but before we could go in we had to be inspected by a woman who dunked a comb in a bucket of disinfectant before yanking it through our hair.

She was the nit nurse! Inside the school the local people had set out sandwiches and drinks for us on trestle tables, but I for one didn’t take anything and I don’t think many others did.

The day had long since ceased to be a great adventure; anxiety had set in. “What was happening to us?” we wondered. I wanted my Mum! But kept quiet about it.

Then a lot of adults came in and stood in front, looking us over before pointing at a child and saying “I’ll take that one!” They were the foster parents.

One by one the children were lead away and the anxiety for those not yet chosen increased as they worried about what would happen to them if they remained un-selected.

Meanwhile Jean was keeping a tight hold on to John and me. She had been told by our parents that she and must not allow the three of us to be separated.

But they couldn’t find anyone to take all of us and John was forcibly dragged away from her and led off. Poor Jean was in floods of tears and desperately worried, feeling that she had failed our parents.

Then she and I were bundled into a car and driven to a very remote cottage, where the woman who lived there at first refused to take us in, but after being threatened with prosecution (billeting was compulsory) she opened the door.

The man who had brought us ran to his car and quickly drove away. “You can’t stay here!” she kept saying, but there was nothing we could do about it.

The cottage was very primitive and not at all like what we were used to. It lacked electricity, gas, piped water or flush toilets, the ground floors were of brick and the lavatory consisted of a bucket in a brick shed at the bottom of the overgrown garden.

There was only a single bed for Jean and I to sleep in. Jean cried all night in spite of me force feeding her some of my chocolate bar in an attempt to make her feel better.

One of the first things we had to do when placed in a billet was to send a postcard home showing our new address. We had been given the postcards back in London and told how important they were, because until they received them our parents did not know where we were.

We younger ones were told what to write on the cards, such as “Dear Mum and Dad, I am very happy here and living with nice people, don’t worry about me.” However it seems that I wrote on mine, “We’ve lost John and the stinging nettles got me on the way to the lavatory!”

“I’ve always wanted to live in a sweet shop! “®

-

After a couple of weeks the Billeting Officer arrived at the cottage and told us to collect our things as we were being moved into the main village (Pulborough, West Sussex). We found ourselves back near to the railway station.

Jean was billeted with the family of a signalman and, to my great delight; I was taken to live with people who ran a shop that sold sweets and many other things. They lived on the premises.

Apparently I said “I’ve always wanted to live in a sweet shop!” and was told that if I was a good boy and did all the jobs they gave me I could have one pennyworth of sweets every day and two pennyworth on Sundays, but I must never help myself.

The jobs included carrying in the buckets of coal, chopping firewood, feeding the chickens, helping on the allotment and, because they had a tea room, doing mountains of washing up.

Very soon they had a surprise because John was also brought to live there, although they had never been asked. He had been living at an outlying farm and was not very pleased about leaving it.

Jean’s billet with the signalman’s family did not work out and she was again moved. That meant John and I saw very little of her because her new foster parents would not allow us to visit. I don’t know why.

Then I was told that John was being moved to another billet because our foster parents could not manage to look after the two of us. He was not far away and I saw him nearly every day, but it did mean that for the first time in my life I was on my own, with no older brother or my sister to look after me.

Another problem for us boys was that because we had been evacuated with our sisters’ school we did not know any of the teachers or pupils other than Jean. When the Village Hall began to be used for the evacuated girls school John and I had to be taught at the Village School.

Initially, as could be expected, there was friction between the village boys and we evacuees, they shouted at us “Dirty Londoners”, we called then country bumpkins and fights often broke out.

Poor John suffered from bullying much more than me, but I was very upset when I saw chalked up messages saying “Vaccies go home. We don’t want you here!” Of course that had been done by a few silly children and was soon stopped, but we evacuees were all suffering from homesickness and all we wanted to do was to go home, but we couldn’t.

Soon after that we were all chalking up big Vs, that being Churchill’s sign for V for Victory. I was given a V for Victory badge that I wore for years. After a year or so John was moved to the Village Hall School, so I saw even less of him.

As the war dragged on.

Earlier I said that we had been told we would be home for Christmas. Many evacuees’ parents defied the government and did allow their evacuated children to return home for Christmas in 1939.

The result was, as the government had feared; many evacuees never returned to the reception areas. My parents were made of sterner stuff and we were not allowed to go home, which was a great disappointment.

In fact our first Christmas back at home was not until 1942, after which we had to return to Pulborough.

What is not generally known is that when an evacuee reached school leaving age they were no longer classed as being evacuees by the government. The allowance paid to foster parents ceased and it was entirely up their parents what happened next.

Of course most evacuees went home, but some obtained work in the reception areas and stayed with their foster parents. For many children the school leaving age was fourteen, but as Jean went to a Central school she left a year later and went back to London.

During the Battle of Britain the skies over Pulborough were the scene of many dogfights and we saw planes explode and come crashing down.

The German fighter planes would zoom low over the village machine-gunning as they went. Anything was their target, even school children, but fortunately none of us were hit.

Then the blitz began and at night we could see the red glow in the sky of London burning.

Very often a policeman would come into school and an evacuee was taken out, we fully realised that that child was probably being told.

Disaster struck the nearby market town of Petworth, where the boys’ school received a direct hit, killing all the children and their teachers.

The threat of invasion turned Pulborough into a fortified village, surrounded by barbed wire, its roads fitted with tank traps. Huge concrete gun emplacements were built, also machine gun posts and slit trenches made behind roadside walls and in many buildings.

Thousands of Canadian soldiers were camped all around the area. Many would call at the sweet shop tearoom, making more washing up for me!

Homesickness-the ever-present problem.

I believe that all evacuees suffered from homesickness, whether they were being well looked after or not. I know I did. It was always there, no matter how hard you tried to keep it away. But in those day’s homesickness was not acknowledged in the way it is now and evacuees showing signs of it were soon told to stop moping around and asked “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” Evacuees became very adept at hiding their inner feelings. You would put on a smiling face and never let anyone see you cry.

That led to many foster parents believing their evacuees were happy, not realising that they were crying themselves to sleep nearly every night.

I managed to hide my homesickness so well that no one knew about it. Apart that is for one occasion that I will never forget. There was to be a concert in the village ball and my foster parents were given a complementary ticket in return for displaying a poster in the shop.

They didn’t want to go so I was given the ticket. Wearing my best suit and tie I felt so important as I was shown to my seat on the night of the concert. It was the first time I had ever been to such an event, especially on my own.

All went well until very near the end when all the caste came on stage, the lights turned to a red glow and they started with some of the songs that my parents used to sing, such as ‘Red sails in the sunset’, ‘The wheel of the wagon is broken’. Then came ‘Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home’. That was too much for me.

I started crying and, try as I might, could not stop. At first no one could see me because the lights were all so low, but then every light in the hail was switched on and the audience stood to sing the National Anthem, the show was over, but I couldn’t stop crying, so I made to get out of the hall as quickly as I could, out into the anonymity of the blackout.

People were looking at me and one woman tried to put her arm round me, but I pushed her away. By the time I had walked back to my billet I had composed myself and showed no signs of any problem, but then I worried for days that someone would come into the shop and say, “Your evacuee was very rude to my wife the other evening”.

But no one did.

Contributed originally by archben (BBC WW2 People's War)

As the days wore on towards Christmas 1939 the streets were more populated, as people drifted back from their evacuation and I heard that my school was open again. It was not to be the same as it provided for boys from all the local schools. But many of the ‘old’ staff was there. The acting headmaster was our former geography master Mr. Martin, known as Bob, after the famous dog conditioning powders. When my father visited the school some time later, he discovered that ‘Bob’ had taught him in his youth. My new form master was a bearded chess fanatic, so we had to have a chess set on our desk and had an hour of the fiendish game every day. More if there was the smallest excuse

Just before Christmas my parents decided quite suddenly, we were to move house. My father had hoped to buy a new house in the autumn, but all building was stopped on the outbreak of war. The main reason for the move was that with the blackout and so many people away, trams and buses stopped running in London before 10pm and my Father, after an evenings work in the City, several times had to walk the last two miles home through the empty pitch black streets. The house selected for our new home was a large semi-detached house in Streatham Hill, high on the top of the South rim of the London basin and more importantly near the tram depot where the late night journeys were terminated. So 48 Kirkstall Road came into my life. It had four main rooms on each floor, two of them over 20 feet square, a rather grand oak staircase and unusually much of the flooring was polished oak or parquet. There was a nice garden, mostly lawn, with a beautiful Plane tree at one corner at the bottom of the garden, this was to save the lives of my mother and I and our dog later. But I must not get ahead of myself. The house stood high off the road, there was a flight of red tile steps up to the porch. It was a cold house. No, it was a very cold house. And probably still is.

The Nation bumbled on through Christmas into the New Year, the war was beginning to show in everyday life, there was less and less in the shops and things were getting dearer. People seemed to be getting greyer and were definitely less smart in their appearance, ladies took to wearing slacks, and these have to be he most unflattering garment ever devised for the female form. As far as I was concerned school was not very educating and the War news was depressing.

I had a visit from my old choirmaster Cyril Barnes. He was now organist of St. Anselms Church near where we used to live. There I was to meet the girl who would become my wife.The vicar was a lovely person, which is more than anyone ever said about his wife. If he had a fault it was that he had been a priest for a long time and made do with 52 sermons. He was an ingenious man, once fixing a small motor onto his bicycle so as to be able to tour the parish more easily. There being no petrol for such frivolity he ran it on paraffin and zoomed around the roads with flames jetting out of the tiny exhaust until the police warned him off the roads.

Just after Easter my Father came home late one morning after his nights work in the City and said ‘You want to be an Architect don’t you?’ I said ‘Yes Dad’. ‘Well then you must know about building, I have arranged for you to go to The School of Building in Brixton’. So in a few days I found myself in this unique school that was hidden away behind the shops in Brixton up against the main railway line. Anything that one needed to know about building was taught there, a truly wonderful place, naturally it doesn’t exist now.

The last part of May brought the worst news of the war. The Belgians and the Dutch surrendered in the face of a huge onslaught from the Germans and we had been betrayed by the French as they failed to use the defences that they had constructed and surrendered meekly to the light tanks of Guderian. Our troops fought their way to the open coast between Calais and Dunkirk and there was the incredible rescue of thousands of men by hundreds of small boats. In England we of course knew little of what was really happening at the time. Vividly in my memory still is being in a classroom of the school which was right against the main railway lines. Suddenly carriages appeared on the track nearest to the school, their compartments were full of dishevelled soldiers, some leaning out of the windows and waving, then another train full of more men pulled into the next track. They were obviously being parked as the stations were full. Eerily we could not hear them or speak to them because of the fixed double glazing of the classroom windows. We went up to a first floor room to get a better view. There was the most amazing sight of aproned women from the houses on the other side of the tracks climbing over their garden walls and running across the tracks carrying jugs of tea and cups for the men in the trains. We held our breath, there are about eight train tracks, all with live third rails!

The country reeled at the double blow of being driven out of France and the obvious incompetence of our military command that had not learned the lesson of how the Germans operated from the way that they invaded Poland. We tried not to think about our open beaches and disorganised Army. I still find it difficult to understand why Hitler decided not to invade, after all the South coast beaches are lovely in June. An interesting view of the situation of the German Army Command is given in the foreword by German General Walther Nehring to ‘Blitzkrieg’ by Len Deighton, in it he says that it was Hitler’s notorious ‘order to halt’ and not proceed beyond a line drawn between Lens and Gravelines on the coast near Dunkirk, that allowed the Allies to evacuate their troops and from them to build the invasion army of 1944. Well as I later learnt in the Army, generals don’t do anything wrong.

So there we were alone with just the Commonwealth. America was prepared to sell us old second hand weapons if we paid for them and went and fetched them. Their Ambassador in London told their President that we were finished. We expected intense air attacks, this lead to a second round of evacuation which was more permanent than the first. My first year class at school was reduced to nine and stayed at that number for the remainder of the three years. This time the expectation was real and the Battle of Britain began.

We soon took little notice of the warning sirens, we couldn’t spend all day as well as all night in the shelters. A solitary aircraft could bring a huge part of the country to a halt if the rules were obeyed. There were no school holidays in London that year. This was so that as far as possible all students could be accounted for during the daytime. The School of Building offered all kinds of occupations for us. We had a free run of its marvellous workshops. I also learnt about photography in the darkroom and how to play snooker. In between our activities we went up onto the roof which offered a wide view to the North right over London to Hampstead. Seeing hundreds of Barrage Balloons ascending all over the capital a minute or two before the sirens wailed is something firmly engraved in my memory.

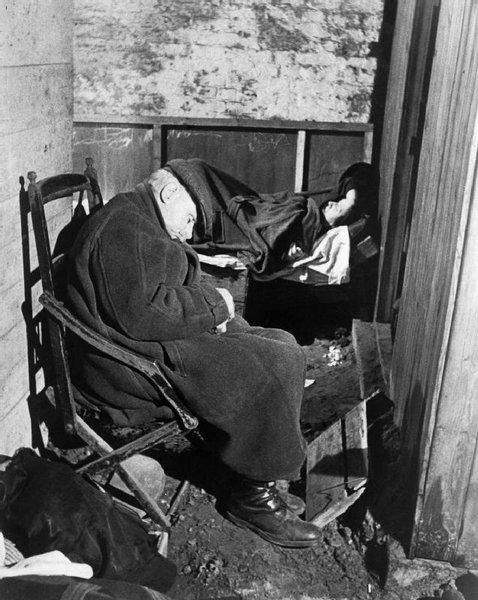

The Battle of Britain was fought over our heads during August and September. The Germans threw hundreds of bombers into the task of bringing us to our knees. Great waves of them destroyed much of the London docks and the surrounding houses, more arrived during the night to drop their bombs into the flaming ruins, thousands of people died. We lived from day to day and night to night. The German air force fighter aircraft were repulsed, which reduced the day bombing. But we knew that defeating the night bombers would be more difficult, particularly as the destruction of so much of our shipping by U boats made the means of fighting the war, fuel, materials, food, more and more in short supply. The failure of Southern Ireland to join us, made the unprotected lengths of our supply routes longer and thousands of lives were lost because of this. The autumn droned on, literally and we got into a routine of finishing our day before 7pm and then collecting our bedding and books and valuables and of course the dog, then making our way to our air raid shelter at the bottom of the garden as the undulating howl of the air raid warning siren filled the air. Years later if I heard the noise in a radio or television programme my stomach would chill, just as it did in 1940. We only emerged from the fug of the shelter into the cold fresh air about 6am, when we heard the all clear siren the next morning.

I must describe the air raid shelter, without which no home was complete. If you had a garden you were supplied with an Anderson Shelter to house all of the persons in your house. Anderson being the name of the Home Secretary at the time it was first issued. It was made of corrugated steel sheet. The body of the shelter was formed with a number of `J' shaped sheets arranged upside down and bolted at the top so as to form an arched tunnel about six feet long. A team of Irish labourers came and dug a hole about three feet deep and erected the sheeting into steel channels and then concreted the bottom and sides up to ground level. The ends of the tunnel were closed with flat sheets. At one end a hole was left so you could get in and at the other the centre sheet was fixed inside the others so that by loosening two nuts with a large spanner, which was thoughtfully provided, the sheet could be pulled inwards to provide a means of escape if the other end became blocked. All of the earth from the excavation was then piled over and around the steelwork. This provided just about the most uninviting place to crawl into as I could imagine. Dad and I set a about making steps so that we could get into the shelter quickly, and a bed on each side, then it was furnished with blankets and cushions. We built a thick blast wall of earth in front of the entrance and hung a curtain over the actual opening. We could not close it with a door, because it was the only way for air to come in. As a final touch we sowed grass seed on the earth covering to make it secure. Everything was in place for us to spend our nights in a damp fuggy atmosphere in the dim light of our little oil lamp.

The year 1940 contained several significant events affecting my life. I met the girl who I would marry, I started my education in my future profession, I began a lifelong obsession with photography, three major events should be enough for one year but there was another. The Fourth event arrived the evening of the second of October, which at the start was like any other. Dad went off to work all night in Faraday House which was one of the major telecommunication centres of the country. It is situated between S.Pauls Cathedral and the river Thames, standing up over the other buildings. It can still be recognised today by its green mansard roof. How it survived I cannot imagine, every other building in the street was bombed flat. The Wren Church of S. Andrew is next door. It was hit by a shower of incendiaries. My Father watched it burn from a window, helpless to do anything, he said that the lead covered dome caved in at its centre looking like a huge raspberry. This area and the docks immediately to its East were major bombing targets. And they were easy targets at that, any pilot just had to find the Thames estuary and follow the silver reflection of the moonlight in the river. We used to breathe a sigh of relief when we heard Dad's key in the door early in the morning.

My Mother and I went into the shelter as usual with Dusty our dog and settled down to read. About 9pm I went to sleep. I woke up to find myself lying on wet earth, Dusty was on top of me licking my face. I could hear my mother asking was I all right. The air raid was banging on outside. It was pitch dark in the shelter, I tried feeling around, incredibly, as I felt along the back wall, I put my hand on my torch. It worked. Our neat shelter looked as if it had been squashed by a giant hand and tipped up at the same time. We had obviously been blown up to the roof as the same time as the earth of the blast wall had been projected through the entrance. I had landed on the soil, but my Mother had fallen back onto the point of the bed boards. We couldn’t get out of the entrance, but as I started to undo the back sheet we heard voices. It was the Air Raid Wardens looking for us. How they found us so quickly I do not know. The night was completely moonless. They dug us out and told us that a bomb had fallen in the garden, but the house was still there and we should go back into it. I scrambled out with the dog, he lead me along the fence down the garden and the Wardens brought my mother in. We could see little in the house and could not put on any lights because the blackout curtains had been blown in. We settled down in a pair of the lounge chairs for the night. It was l0pm. We slept little, loose doors and windows were banging all night. The air raid slowed down after midnight. It was a miserable cold night, it seemed an eternity before dawn and the all clear siren came. At first light I set out to look around the house. It was quite incredible, the main part of the house was not damaged except for one small broken window. All of the walls were untouched except for one crack, the rear ground floor windows of the lounge had been moved from their proper places, hence all the banging of the windows, as they did not fit their openings any more.

The night before and every previous night, before we went into the shelter my Mother had taken all of the china from the big Dutch dresser in the kitchen and stacked it on the floor of our walk-in larder. The bomb blast had blown its door off its hinges, and jumped all of the jars, containing a seasons jam making, off the larder shelves onto the crockery below. Neatly nestling in the mixture of jam and broken china and glass was our wireless. I picked it up and plugged it in and it worked away merrily and continued to do so for the next 7 years. I went upstairs along the corridor to my room at the back of the house and opened the door. There should have been two large sash windows in the wall opposite, there was only one. The other was placed neatly on my bed, all of the glass intact, with its head on my pillow. I looked out of the hole in the wall. What I saw was unbelievable. The bomb had hit the ground half way down the garden, probably about the line of the side fence to our neighbours, there was a deep crater occupying the whole length of the garden and the width of both gardens, that is about 90 feet in diameter. Great boulders of London clay had fallen back into the hole, some over ten feet long. Our shelter and any sign of our flowers and vegetables could hardly be seen. Coming out of the shelter I had been lead by our dog along the other fence. If I had tried to walk where the path had been I would have gone straight down the hole, which was over twenty feet deep.

During the morning we had a stream of visitors, doctor, damage repairs, people to arrange replacement of household essentials, crockery yes, jam no, and a bomb expert. He said you were very lucky that we had a wet September so that the 250 Kg bomb went down a long way. He found and gave me, for a souvenir, as if I needed one, the bomb detonating rod. Then he stood back and looked at our plane tree, which was looking a little sad. "That tree saved your life" he said. "See the path of the bomb though the tree in those broken branches, before it bounced clear it was heading straight for your shelter". Then I went to school. We were bombed last night. Oh really, you're all right then. We didn't get trauma councillors then, not that we would have known what to do with one. We just got on with our lives, grateful indeed that we were still living. Months later another group of Irish labourers came and filled the hole in and put up a new fence. If you didn't know that the garden should really be two feet lower you wouldn't notice any difference.

My Fifteenth birthday came and went, the only thing that I can remember about it was that I had a tyre puncture on my bicycle on the way home from school at mid-day. I leant my bike up against a lump of clay at the side of the crater, patched the inner tube, had my dinner and went back to school.

Two eventful years for a young boy but it was only 1940, there was a lot more to come.