Incendiary Bomb at Jeffreys Road

Description

Incendiary Bomb :

Source: 24 hours of Blitz Sept 7th 1940

Fell on Sept. 7, 1940, at 8:46 p.m.

Present-day address

Jeffreys Road, Stockwell, London Borough of Lambeth, SE11, London

Further details

Jeffreys Road, Clapham SW4, London, UK ; Suspected presence of IB

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

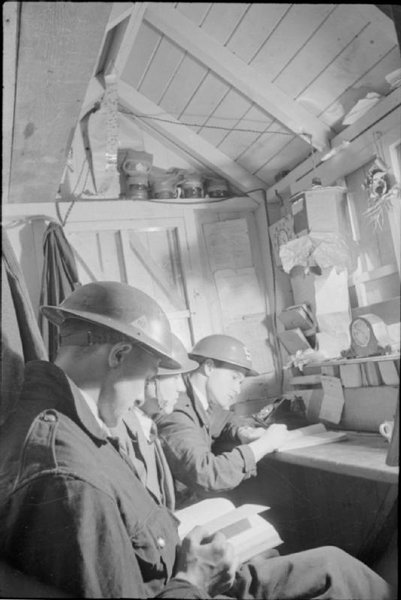

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by Peter R. Marchant (BBC WW2 People's War)

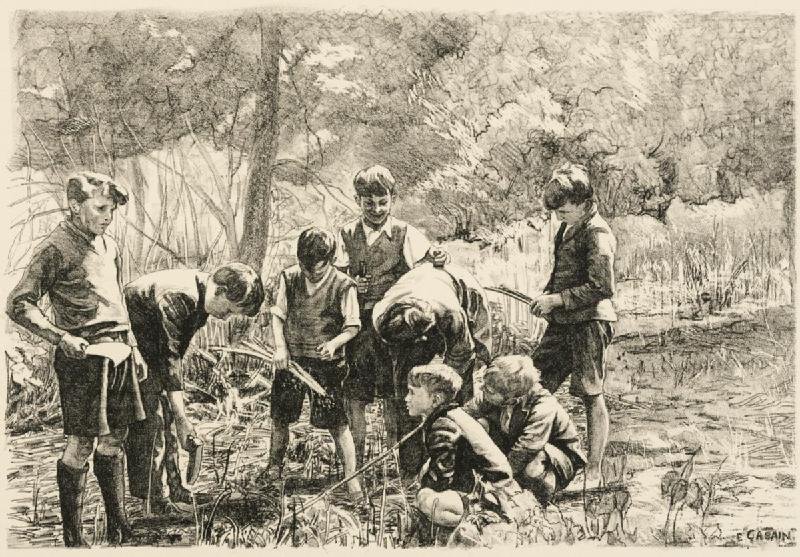

Don’t tell Adolf about the wonders of country living for a small city boy. Don’t tell Adolf about the exciting playgrounds of the bomb damaged houses. Don’t tell Adolf about the excitement of the search lights and the guns and don’t tell Adolf how he changed my early childhood into an adventure often frightening, but with vivid memories I recall to this day.

My very first ever memories are framed by the war. It must have been sometime in 1940 when I was almost four years old. Our family, my Mum and Dad and my older sister Thelma, were living in a Victorian row house in Clapham, London. This area has now become quite fashionable with house prices equal to my father’s life time income. Then, it was a working class neighborhood, clean and respectable, populated by postmen, mechanics and lorry driver tenants like my father. The only thing I can remember about the interior of the house was the Morrison shelter in the center of the bedroom. There I spent many weeks of isolation with a severe attack of the mumps in uncomprehending discomfort, picking at the grey paint of the cage unable to take anything more solid than my mother’s blancmange and barley water, her remedies for all known human ills. I’m sure my parents were grateful the authorities provided us with a combination bomb shelter, table and sick bed, although I wonder was anyone actually saved by this contraption? This was a time when one’s betters weren’t questioned; my family rarely doubted they must know what was best for us. For those who know only about more serious bomb protection the Morrison shelter consisted of a bed surrounded with stout wire mesh and a steel top on four corner legs about the right height for a table. The idea was to prevent the occupants from being crushed to death under falling masonry, a small sanctuary to wait in, listening for the scrape of shovels and praying to be rescued before the air ran out. In addition to the ugliness and awful paint its major flaw was the assumption that we would all be in bed when the house collapsed, a family so stunted by food rationing that we were able to sleep together comfortably in a double bed. Did Adolf realize the Morrison was part of the propaganda war designed to show the Germans that we English were just as viral as the master race; a people that only needed a tin bed as protection from their bombs?

As I got better I was allowed to play in the garden at the rear of the house. I remember it as long and narrow flanked on one side by the windows of a small factory making parachutes, or bully beef, or some other necessity for killing the enemy. The weather must have been hot as I recall the young women talking to me through open windows. They seemed happy in their factory routine and the pound or two a day they earned which was probably the best money they had ever made. Or were their smiles just for the rather shy little boy they gave the small pieces of chocolate and orange segments then as rare and sought after as black truffles? If there’s a page in the calendar that can marked as the beginning of my generally good relations with the opposite sex it’s probably spring 1940.

There are many more memories that come to me clearly but they are mixed in a jumble of time. It must have been after the serious bombing of London started in summer 1940 that my sister and I were evacuated. We were all caught up in a great sea of events and

if the choice for our parents was having us with them so we could all be reduced to rubble together or safe country life for their children, it was not difficult to decide which train to catch. An adult knows the terrors and uncertainty of the world and has worries beyond tomorrow but a small boy knows only the moment and thinks of an hour as an eternity if an ice cream is promised.

We were sent to live with a Mr. and Mrs. Daniels and their two sons on their small holding at Gidcott Cross, a junction of narrow country roads about six miles from the market town of Holsworthy in the county of Devon. The surrounding country was divided into small irregular fields on a plan lost in antiquity, surrounded by tall hedges topped with thick bushes and occasional trees.

Many evacuees have grim stories to tell and we were very lucky to be in the care of a loving couple who treated us like their own. The Daniels had a few acres near the house and some additional pasture rented nearby. On this they kept a few milk cows, all with pet names, Daisy, Sadie and Jessie, a pig or two and a muddy barnyard full of chickens. A pair of ducks stayed most of the year in a narrow rivulet that ran around the house. A female dog Sally, always ready for a rabbit hunt, followed us around everywhere when she was not ensuring a new supply of terriers. The farm house had, or rather has, as it seems little changed over the years, thick rough walls yearly whitewashed, four or five rooms in two stories under a thick thatched roof. The Daniel’s house was at the foot of gently sloping fields set back from the road with a pig barn on the left and the milking shed and hay storage on the right of the heavy slab stone front path.

Mr. Daniels was a member of the local Home Guard, a group of tough wiry men too old for immediate military service. There were no blunderbusses or pikes, but modern weapons were in short supply. Mr. Daniels had upgraded to a worn double barreled shot gun a deadly weapon in his hands as all the rabbits knew. At lane intersections old farm wagons loaded with rocks were ready to be pushed into a road block. One clever ruse was redirecting the road signs, a confused German being thought better than a lost one. Any one advancing down the road to Holsworthy would find them selves in Stibbs Cross with only one pub, a much less desirable place to take over. The home guard met regularly near our cottage for drill and comradeship. It was so popular that the institution lived on well after the war as a social club. These men knew every blade of grass for miles around and would have caused any German paratroopers much annoyance if Adolf the military genius had ordered landings in this remote corner of England.

When they were not repelling German invaders the Home Guard kept an eye on the Italians in the area. Up the road was the Big Farm, big because it had a barn large enough to house a half dozen trustee Italian prisoners of war working the land. Riding on farm wagons pulled by huge shire horses, as petrol was very scarce, they would stop outside our cottage on their way to the fields. They looked like old men to me though they were just young boys probably not yet 18, endlessly happy to be out of the war, captured by a humane enemy and ending up in this idyllic setting. They carved wooden whirligig toys with their pen knives for me and the nostalgic Italian songs they sang I can hear in my mind to this day.

It was a wonderland for we city kids with farm animals, the open country to explore and no shortages of food. The farm was in most ways self supporting, if you wanted a stew you shot a rabbit or two, or cut the throat of a chicken. I helped with the endless farm chores collecting eggs every day from the nest boxes, when the chickens were good enough to cooperate. Many chickens didn’t appreciate the conveniences we provided and made the job into an adventure searching the hedgerows for errant layers. No tinned or horrible dried food for us, everything was fresh as the vegetables pulled from the ground within sight of the front door. When we eventually returned to London my sister and I were noticeably well fed and quite fat, the battle for my waist line probably goes back that far!

Without modern conveniences it took most of the daylight hours to keep the house running and everybody was expected to pitch in. Another of my ‘helping’ jobs was to help fill the water barrel. With a small boy’s bucket and many trips I walked up the road a hundred feet, to the well hidden in a hedge tangled with wild roses, pushed the wooden cover aside and, after tapping on the surface to send the water spiders skimming out of the way, dipped in my bucket. This taught country ways very quickly and water became a precious commodity to be recycled for many uses until it was finally used to scrub down the flag stone floor. The water was heated in a large black iron kettle hung on a chain over a log fire in the inglenook fireplace the only source of heat in the house. Cooking had changed little over hundreds of years and savory stews and soups were made over the burning logs in large iron cauldrons. There was no electricity or gas in our cottage and finer cooking required Mrs. Daniels skillful fussing with a flimsy paraffin oven in the back room from where emerged a stream of delicious pasties, or covered pies, filled with a range of edibles that would have surprised even a Chinese cook. These pasties were brought out every meal covering the table with a smorgasbord of dishes from ham and egg, potato and wild berries, until finished. The men took them into the fields stuffed in their Home Guard haversacks and with a jug of local cider and after grueling days in the sun bringing in the harvest ate dinner sprawled against the hay stacks. The days ran with the cycle of the sun; the evenings were lit sporadically with a noisy pressured paraffin lantern and bedtimes were shadowy with the light of candles.

I remember my evacuation with the Daniels as an idyllic time although now I detect there must have been a feeling of abandonment and bewilderment long buried. One of my parent’s visits I didn’t recognize the lady with my father as my mother had just started wearing glasses. Later on, another visit, I wandered the lanes all day looking for them on a country walk they had taken and was tearfully relieved to find them sitting in a field eating sandwiches having no idea how upset I was at being left. Evacuation must have had a profound effect on many young children like me. My wife thinks that this experience is the cause of many of my strange ways and quirks of personality although I claim genius has its own rules.

My sister and I were returned to London after a couple of years in the country, the precise timing is vague in my memory. The aircraft bombing was much less now although the sirens still wailed for the occasional raid setting the guns booming on our local Clapham Common. I wish I still had my treasured collection of shrapnel from the antiaircraft shell bursts that rained down razor sharp fragments of torn steel and made being outside as dangerous as the bombing. These would be poignant reminders of this time so distant it feels like another life. Memories of my best friend Basil who always managed to find the pieces with serial numbers, the most coveted in our collection.

I recall one night the warning sirens sounded and the sky was lit by searchlight beams probing for the attackers. Within minutes the street was as bright as the sky, plastered with small oil filled fire bombs. They were everywhere causing small fires in the gardens and on the roofs of our street. One slid through the slates and wedged itself under the cooker of our upstairs neighbour, Mrs. Tapsfield. My father spent the night running up and down the stairs carrying buckets of dirt from the garden and spraying the cooked cooker with a stirrup pump. I can, even now 60 years later, see my mother next morning standing on a chair with a hat pin puncturing the hanging bladders of water filled ceiling paper from the flood upstairs. The fire bombs caused a lot of minor damage but they were all damped down and none of our neighbours lost more than a room or two. For many years after the sheet metal bomb fins would turn up when a new flower bed was dug deep. The trusty stirrup pump gathered dust in the coal cellar ready in case it was of need in another war in the new atomic age.

England was a very grey place with some rationing into the 50’s. For us kids Clapham was a wonderland of bomb damaged play houses and vacant rubble strewn lots. There were complete sides of buildings missing leaving the floors with wallpapered rooms precariously suspended. Bath tubs and staircases were stuck teetering to a wall with no apparent support stories up and the cellars were half filled with debris with only dusty tunnels for access. You can imagine the games these inspired for us boys. A special game was attacking and defending the half flooded abandoned concrete gun emplacements on Clapham Common and exploring the communal air raid shelters dug in the square. If only our parents had known!

How do you remember the events of a war time childhood? Memories are like a damaged film, occasional clear scenes separated by long stretches scratched and out of focus.

Through the often repeated stories distorted by their retelling; by today’s chance incidents that start a flow of thoughts to a half forgotten scene. Was it a page in a book or an E mail from a friend, who can tell the truth from imagination? I cannot be sure of the exact timing and the precise details of my experiences in WW2 they have been rounded off by time, and in this diary I have done my best. Although the accuracy may not be perfect and who can be sure in the valley of the shadow of memory, I hope to have conveyed the atmosphere of my experiences in these anecdotes.

Contributed originally by Jean_Jeffries (BBC WW2 People's War)

First thing I remember of September 1939 is being told we must deny any Jewish family connections.

We lived in a fairly large house opposite Clapham Junction, South London. We quickly moved house to one further from the busiest railway junction in London, which was a prime target.

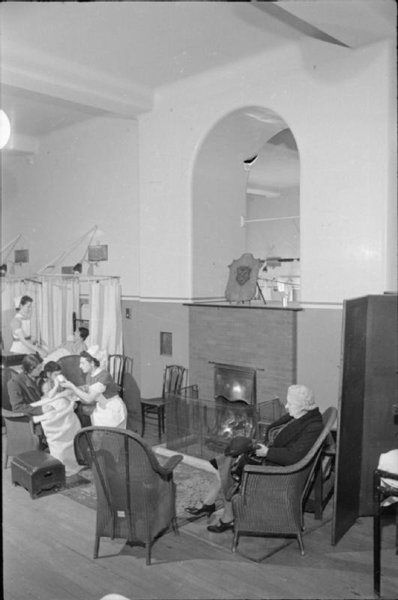

Our first Air Raid Shelter was the London Transport underground tube station. Bunks had been placed along the platforms and each evening, we would arrive with a few possessions and take our place in a two-tier bunk; the only privacy was a blanket suspended from the top bunk. At this time, my father was a fire-fighter so mum was alone in the Tube with two small children. If one wanted the loo, we all had to go, complete with any possessions - teddy bears and dolls! I was very nervous, not of bombs but of some of the weird people who we were living so close to.

If we were out during the day and a siren sounded, some of the shops would open the trap-door in front of their shop (which was used for deliveries) and we'd scuttle down the ladder. My favourite shop was David Greigs, us kids were spoilt there. I always dawdled outside hoping the siren would sound, never giving a thought to bombs! Then the Government installed the Anderson Shelter for each family. It was sunk into the ground for about 3ft and measured roughly 9ft by 9ft. It had two, two-tier bunks and accommodated our 6 family members with a squeeze. This was luxury after the Tube, but, being below ground level with no ventilation, it was damp and began to smell. Everything went mouldy and I still recognise the smell. I hated the toilet arrangements - a bucket outside for use during a lull, brought inside for use during a raid. During this time, my brother, aged 5, developed asthma and my father T.B., although he was not aware he had it. Dad got his calling-up papers and was turned down on medical grounds, but the examining doctor refused to tell him why or warn him of the Tuberculosis they'd found. I heard my parents worriedly discussing it and I was glad he wouldn't be going to war.

The evacuation of London began. I was ready to go with my gas mask, case and with a label tied to my coat. My brother was too ill to go, so, at the last minute, my mother decided to go also and take him away from London. So we set off for some vague address in Bakewell, Derbyshire. Families in safe areas were ordered to take in evacuees and, in this house, we were resented and made to feel very unwanted. Food, already scarce, was even more so for us. Our mean hostess fed her own family well with the rations intended for us. Within a month we had left and it was years before I ate a Bakewell tart or admitted Derbyshire was beautiful!

Next, we reached an old farm cottage in Bampton, Oxfordshire. Our landlady was a Mrs Tanner, a warm-hearted person who made us welcome with a full meal and a blazing fire - what a difference!

Mrs Tanner was the wife of the local Thatcher. They kept livestock for their own food, as country people did then. Despite being Cockneys, we had come from an immaculate home with electricity, hot water, a bathroom and an indoor toilet. We now found ourselves in this warm, well-fed friendly cottage with friendly bed bugs, kids with head lice, a tin bath hanging on the garden wall and a bucket'n'plank loo in the yard. The loo had a lovely picture of "Bubbles", the Pears advert, hanging on its wall - very tasteful.

On Thursdays, all doors and windows were tightly closed whilst we waited the coming of the Dung men; two gentlemen wearing leather aprons emptied everyone's buckets into their cart. What a job!

My brother was very much worse, skinny and weak with breathing difficulties. He spent time in hospital and mum stayed with him. Mrs Tanner treated me like yet another grandchild and I soon settled happily into my new way of life. Mum asked her if she would take me to the town, a bus ride away, to get new shoes and some clothes. Off we went on what was literally a shop-lifting spree. I was both frightened and excited and sworn to secrecy. Mrs T. kept the money and the coupons and mum was thrilled to have got so many bargains. I never told her! But, when I wore my new shoes or my finery, I always dreaded someone asking me questions. I laid awake at night rehearsing my answers. I was never tempted to try it myself. When I see Travellers, kids, I often think "that was me once". After a year of my idea of heaven, mum decided to return to London to see if the hospitals there could help little Eddie. We got back just in time for The Battle of Britain; I'm glad they waited for us. I was so homesick for Bampton that I even contemplated running away to try to go back. Although I settled down, I still think of Bampton as my home and, after 63 years, I still go back for holidays. Just one year made such an impression on me. It was so carefree and I enjoyed some of the jobs with the animals.

During the time we were away, my dad had carried on with his job and Fire-fighting in London. Our home had gone, so we stayed with an Aunt until we got somewhere to live. Empty houses were requisitioned by the Authorities, who then allocated them to those who needed them. My parents applied for a house, explaining that Eddie needed to be near a hospital, but they were told that, as the father was not in the forces, they did not qualify for accommodation. They were heartbroken as a doctor had informed them that, without a decent home, Eddie would not live long. My father insisted on volunteering for any of the forces, but was once again declared unfit. Eventually, after mum worried them every day, we were given two rooms in a small terraced house, sharing a toilet with another family. There was no bathroom and we were made to feel almost like traitors with frequent remarks directed at my dad. Even at school the teachers singled us out with "anyone who's father is not in the forces will not be getting this" - this could be milk or some other treat we regarded as a luxury. One teacher was so obsessed that today she would be considered mentally unbalanced. A project she gave us 10year olds was to devise tortures for Hitler or any German unlucky enough to survive a plane crash. I cheated and copied one from a book.

Our shelter was now a reinforced cellar. It was dry and spacious and, during heavy bombing, some of our neighbours joined us and we had what I considered to be jolly times together. Food was in very short supply; although we had ration books, there was not always enough food in the shops. I was sent to queue up, then mum would take over while I queued again at the next shop with food, where we repeated the pattern. I once reached the counter before mum got there; we were waiting for eggs. I got 4 eggs in a paper bag and, as I left the shop, I dropped them. Carefully carrying them back to the counter I told the assistant she had given me cracked eggs. I was shouted at and called a lying, nasty little girl but managed to obtain 4 replacement eggs. I just could not have told my mum I'd broken them.

A neighbour of ours was a fishmonger, poulterer and game merchant. He sometimes had rabbits for sale; they were always skinned and usually in pieces. After bombing raids, there were often cats straying where their home was destroyed, or dogs wandering about the streets. We think our fishmonger solved this problem. I believe most women realised the meat wasn't quite what they wanted but had to have some meat to put in the stew. Luckily we had a vicious wild cat I had taken in and being so spiteful, she lived a long and happy life, occasionally bringing home a piece of fish. How she managed this I don't know. Could it have been bait for a lesser cat?

School was rather a shambles. We had our classes in a shelter, that is 2 or 3 classes at a time; as there was insufficient room for all the children we had mornings or afternoons only. The other class we shared our shelter with always had such interesting lessons! I feel awful about admitting this but the education system was so easy to play truant from. If you didn't turn up they assumed you'd been bombed or sent away to safety. A couple of friends and I used to ignore the danger of air raids and go to the centre of London where we could be sure of meeting American servicemen. We begged for gum or chocolate from them, then had to eat or hide it before going home. At no time did we ever think of how our families would have no idea where we were if we never came back. It's rather frightening really. Our excursions came to an end when, on a very wet day, mum came to meet me from school with an umbrella. After waiting until all the kids had left, she went in to see our teacher who said I had not attended for some time and thought I had gone back to Bampton. Boy, did I get a beating! She was as vicious as my cat but not as lovable.

One night we were in our shelter when a neighbour called us to come out to see the incredible amount of German planes that our boys were shooting down. We stood outside in the street and cheered, linking arms and dancing. The next day we heard on the radio that they had not been shot down but were a new weapon - the Doodle Bug. From then on I understood fear. I don't know what triggered it but I joined the ranks of the old dears who swore they recognised one of ours or one of theirs. I henceforth scrambled to get my pets into the shelter as soon as we heard the siren. My dog soon learnt this and was first down; her hearing being keener than ours, she could hear the siren in the next town before ours. Soon we had Rockets. There was no warning with them. The first one we saw was on a summer's evening when my friends and self were practising the Tango on the street corner. We were singing "Pedro the Fisherman" as a whine came from above our heads, followed by a cloud of dust and then the impact and sound of the explosion. Four screaming dancers rushed for shelter. We knew many of the people who had been killed or injured and it seemed too close to us. It never had been safe but we hadn't noticed it before, now I did, worrying, "where did that one land?" "Is it near dad's shop or near our relations?" I guess I'd grown up but it was so quick. I was twelve, learning to tango and worrying about our family. I decided I would join the Land Army as soon as they would let me; I'd heard one no longer needed parents' permission. This was not anything to do with the war effort. I simply wanted my life back in beloved Bampton. My feelings were mixed when the war ended, no more terrifying Rockets but trapped in London with no chance of getting away until I married!

Contributed originally by 2nd Air Division Memorial Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jenny Christian of the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library in conjunction with BBC Radio Norfolk on behalf of Frank L Scott and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Part one

I was eighteen, going on nineteen, when the storm clouds of war started to gather. Life was good ; a happy home, loving and devoted parents and family, sound job prospects and a variety of interesting hobbies and out-door pursuits. All this adding up to an enjoyable and hopefully peaceful future. Life was indeed worth living!

My dreams were shattered on that morning in early September 1939 when the sirens sounded throughout the land warning 'Englanders' of an immediate air attack when the suspected might of the German Luftwaffe would rain down upon us.

Most people that could, and were able, ran for cover long before the mournful wail of the penetrating sound of the air-raid sirens had faded away.

My family consisting of Mother and Father, two sisters, three younger brothers and an elderly Grandfather took to our heels and made for the conveniently placed 'Anderson' shelter dug into the back garden. I can't remember the exact measurements of that particular type, but I do know that to house nine adults for any length of time, as it eventually did for several months to come, has to be experienced to be believed. Not only was it very uncomfortable in such a confined space but there was always a fear of the unknown horrors of bombing raids.

Within the shelter, there was the cheerful chatter to keep up our spirits but outside there was an uncanny silence which was broken some time later by the ALL CLEAR signal. A sound we got to love and hear. Nothing happened that particular day and we remained unscathed.

The sound of that very first warning at about 11 o'clock on Sunday 3rd September 1939 will long remain in the memories of many folk, the elderly and not so young, and was a discord we all learnt to live with and to rejoice endlessly to the welcome sound of the ALL CLEAR.

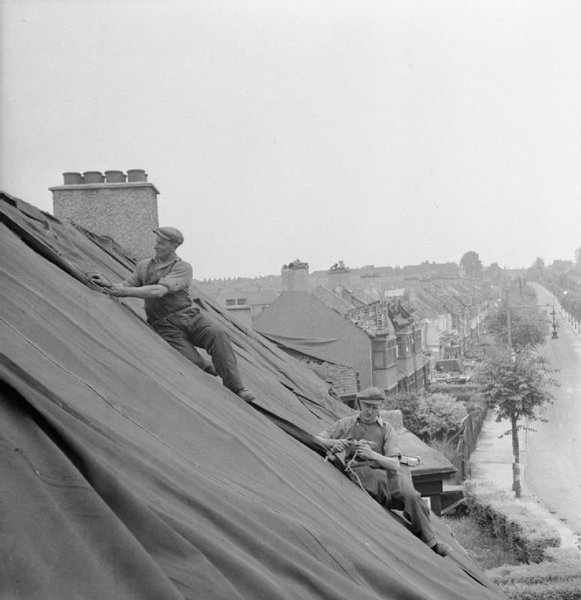

This situation continued for many months with warnings of imminent raids which came to nothing. So began the 'phoney war' as it became to be known. Because of the continuous interruptions caused daily when enemy aircraft were unable to penetrate the air defences, spotters were placed on rooftops of factories, offices, power stations etc., to warn workers only when there were signs of impending danger.

Unfortunately, this was rather short lived and many large towns and cities suffered badly when the German High Command decided to step up and concentrate on a more devastating and annihilating blow, in particular to the civilian population.

My personal experience of this period of time was when taking a girlfriend to a cinema in Elephant and Castle area of London and to be informed by the Manager of the cinema that a heavy bombing raid was taking place in the dock area of the East End. Not that that had much significance to a couple in the back row, who continued there until the bombing got worse and the Manager informed those remaining that the cinema was about to close.

Most people that were able to went underground that evening and it wasn't until the ALL CLEAR sounded in the early morning at daylight that they came out again and went about their business.

Living not far from this area, my first thoughts were for my family and I wished to check on their welfare as soon as possible. Because of the ferocity of the raid, there was much local damage and fires were raging everywhere, accounting for endless lengths of firemans' hosepipes to be trampled over in search of public transport which, by that time, was non-existent. Having escorted my girlfriend home which, unfortunately, was in the opposite direction to the one I would have wished to get me home quickly, but eventually I made it and found them safe and sound. A block of flats nearby had taken a direct hit during the raid.

This signalled the beginning of endless night after night bombing raids on London and 'Wailing Willie' would sound without fail at dusk about the time that mother would be putting the finishing touches to the picnic basket that the family trundled to the garden air-raid shelter. Not too often, but some nights for a change of scenery, or further company, we would go to a communal shelter but must admit that we all felt most secure at 'ours'.

So, life went on, come what may, raids or no raids. All went of to work the next morning trusting and hoping that our work place would still be there. Battered or not, running repairs would be performed and it would be 'business as usual'.

My father, being in the newspaper distribution trade and a night worker would clamber out of the shelter in the early hours but would return occasionally during the night to see that all was well. He would also drop in the morning papers which were often read beneath the glow of the searchlight beams raking the darkened sky in search of enemy aircraft. An additional item on one particular raid was when a nearby gasometer near the Oval cricket ground was hit and a whole cascade of aluminium flakes came drifting down in the light of the search light beams.

Being in 'Civvy Street' at that time, and in what was considered a reserved occupation with a company of manufacturing chemists, my only contact with the war and ongoing battles in various theatres of war was through the press. It was not until that little brown envelope appropriately marked O.H.M.S. fell through the letter-box did my involvement with the military begin.

"You will report" it began, and so I did to the local Labour exchange when it set the ball rolling with regard to medicals, which arm of the service, date of call up etc. I also remember that my company deducted my pay that day. Something I never forgave them for and therefore had no wish to rejoin them on release from the forces.

Came the day, or rather it very nearly didn't! One of the most frightening and devastating attacks on London came that night. The railway station that I had to report to for transport to camp had been put out of action and I can remember clearly seeing passenger carriages hanging onto the roads from railway bridges. Plan 'B' was immediately put into operation and road transport was made available to take us "rookies" to the next station down the line.

The Military Training Camp on the borders of Salisbury Plain became home for the next six weeks when one went through all the motions of becoming a fighting soldier, with discipline and turn-out being the Order of the Day. Whatever one says about Training Sergeants I think our Squad must have struck lucky because we decided to have a whip round and buy him a parting gift before our leaving camp and being drafted to a searchlight mob. Thus ended basic training in the Royal Artillery.

The next venue was over the border; a searchlight training camp on the West coast of Scotland. Within a very short time and very little action, boredom set in and a Regimental office notice calling for volunteers for Airborne Divisions prompted a few of my mates and I to put our names forward. Knowing the outcome of some of their eventual encounters in later battles I am thankful now that an earlier posting took me to a newly formed Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment of which I am justly proud.

Whilst serving with a searchlight Battery Headquarters in Suffolk, apart from the usual flak and hostile fire being an every day occurrence, Cupid's dart took a hand when the A.T.S. became part of the Establishment and a cute little red-head arrived on site. A war-time romance followed but a further posting from that unit took me to another part of the country. As the saying goes "Love will find a way" and it did for we kept in touch until distance and timing took its toll. That was over 50 years ago and through a twist of fate, a news item that appeared in a national newspaper put us in touch again.

My Regiment, the 165 H.A.A. Regt. R.A. with the fully mobile 3.7in gun had many different locations during the build up to D Day but it was fortunate enough to complete its full mobilisation for overseas service in a pleasant area on the outskirts of London. This suited me fine as it was but a short train journey to my home and providing there was no call to duty I would take the opportunity of going A.W.O.L. and dropping in on my folks for a chat and a pint at the local. However, I always made a point of getting back in time for reveille and no one was the wiser. It was also decided about that time that every man in the Regiment should be able to drive a vehicle before proceeding overseas so that was another means of getting up town for a period of time.

Inevitably all good things come to an end and we received our "Marching Orders" to proceed in convoy to the London Docks. The weather at that time was worsening putting all the best laid plans 'on hold'. Although restrictions as regards personnel movements were pretty tight some local leave was allowed. It would have been possible for me to see my folks just once more before heading into the unknown but having said my farewells earlier felt I just couldn't go through that again.

Part Two

With the enormous numbers of vehicles and military equipment arriving in the marshalling area and a continuous downpour of rain it wasn't long before we were living in a sea of mud and getting a foretaste of things to come.

To idle away the hours whilst awaiting to hear the shout "WE GO", time was spent playing cards (for the last remaining bits of English currency), much idle gossip, and I would suspect thinking about those we were leaving behind. God knows when, or if, we would be seeing them again. By now this island we were about to leave, with its incessant Luftwaffe bombing raids and the arrival of the 'Flying Bomb', had by now become a 'front line' and it was good to be thinking that we were now going to do something about it !!

All preparations were made for the 'off'. Pay Parade and an issue of 200 French francs (invasion style), and then to 'Fall In' again for an issue of the 24hr ration pack (army style), vomit bags and a Mae West (American style). Just time to write a quick farewell letter home before boarding a troopship.

Very soon it was 'anchors away' and I think I must have dozed off about that point for I awoke to find we were hugging the English coast and were about to change course off the Isle of Wight where we joined the great armada of ships of all shapes and sizes.

It wasn't too long before the coastline of the French coast became visible, although I did keep looking over my shoulder for the last glimpse of my homeland. The whole sea-scape by now being filled with an endless procession of vessels carrying their cargos of fighting men, the artillery, tanks, plus all the other essentials to feed the hungry war machine.

The exact role of my particular arm of the Royal Artillery was for the Ack-Ack protection of air-fields and consisted of Headquarters and three Batteries, each Battery having two Troops of four 3.7in guns, totalling some 24 guns in all. This role was to change dramatically as we were soon to discover. In the Order of Battle we would not therefore be called into action until a foothold had been successfully gained and position firmly held in NORMANDY.

The first night at sea was spent laying just off the coast at Arromanches (Gold Beach) where some enemy air activity was experienced and a ship moored alongside unfortunately got a H.E. bomb in its hold. Orders came through to disembark and unloading continued until darkness fell. An exercise that had no doubt been overlooked and therefore not covered during previous years of intensive training was actually climbing down the side of a high-sided troopship in order to get aboard, in my case, and American LCT.

This accomplished safely, with every possible chance of falling between both vessels tossing in a heaving sea, there followed a warm "Welcome Aboard" from a young cheerful freshfaced, gum chewing, cigar smoking Yank. I believe I sensed the smell of coffee and do'nuts!!

Making sure that the assigned vehicle for my entry into Normandy and beyond was loaded aboard I settled down, anticipating WHAT, but surveying the panoramic view as we approached the sandy shore by now littered with the remains of the earlier major onslaught.

Undoubtedly one couldn't have been too aware of the incoming and outgoing tides as the water was far too deep at the beach-head and found it necessary to cruise around until late into the evening before it was decided to make for the shore come what may!! By then it was time to join the other members of the regiment's advance party in the Humber staff car which included driver, a radio operator, the C.O. and Adjutant.

Following the dropping of the anchor, the loading ramp was immediately lowered to the accompaniment of the sound of the engines breaking into life. I think at that point the two officers became aware that we were still in 'deep water' for they decided to climb onto to roof of the 'Z' vehicle as it proceeded down the ramp. In spite of seeing the sea water gradually climbing half way up the windscreen the O.Rs feet remained reasonably dry and we made the shore with the aid of the four-wheel drive.

At the first peaceful opportunity it was essential to shed the vehicle of its waterproofing materials and extend the exhaust pipe. The canvas parts of this exercise I decided to keep, as I thought that they would be useful (time permitting) for lining ones fox-hole, which I later found to be ideal.

My ancient tatty looking 1944 diary informs me that I slept in a field and awoke at 05.30hrs to a glorious sunny day, that I washed in a stream,sampled my 24hr ration pack, saw my first dead jerry and that General De Gaulle passed the Assembly Point.

I must admit that without the aid of my diary that I managed to keep throughout the war (something that I could have been very severely reprimanded for had it been known at the time) and the treasured letters that my Mother retained until her dying day, I could not possibly remember all the most intimate details of my soldiering days.

Returning to those early entries, whilst enjoying the pleasure of a quick splash in a neighbouring stream I became aware of some girlish giggling in the adjoining bushes and felt that this was an early indication that the natives were friendly.

We proceeded inland, the Sappers having done their stuff and prepared safe lanes amid endless rows of tape with the deathly skull and crossbones indicating ACHTUNG MINEN, it was decided to set up Regimental H.Q. in the area of Beny-sur-mer.

During a check halt en route I noticed that a small area of corn a few yards into a vast cornfield had been disturbed. Taking a chance and feeling inquisitive I decided to investigate. And there it was the ENEMY, but proved not to be too much of a problem. How long he had been there I do not know. He was lying on his back, his feet heavily bandaged no doubt through endless marching, his Jack Boots placed beside his body. I also notice hurriedly that his ring finger was missing? Someone's Son, someone's Father, someone's brother, someone's liebe; what a ghastly business war is !!

It occurred to me that all my observations of German manhood from the then current movies and other sources gave one the impression that they were a somewhat super human race; six foot tall, blonde and blue-eyed. That is what the Fuhrer had aspired to no doubt but I was rather taken aback to see the first column of German prisoners passing by, some short, fat, bald, spectacled etc. etc. a straggly pathetic bunch, tired, weary but some still with that aggressive look in their eyes, some glad that at least the war and the fighting were over for them.

Several moves to different locations were made in the ensuing weeks, also being 2nd Army troops, we were at the beck and call of any Corps or AGRA needing support and CAEN had to be taken at all cost.

Being on H.Q. staff one of my 'in the field' roles was to travel with the Staff car into the forward areas and reconnoitre sites prior to the deployment of the heavy artillery. Here I would remain until the last of the units had passed through that check-point with the expectation of being picked up sometime later when the whole procedure would continue again with a type of leap-frogging action.

Following days of constant heavy shelling and later to watch a 1000 bomber raid from the outskirts of that well defended town of Caen it finally fell. Having dug ourselves in and around an orchard in the Giberville area, east of Caen, some late evening mortar fire sadly killed our Second-in-Command (Major Finch) when the shell struck an apple tree under which the officers were playing a game of cards. Here again my diary notes "heavily shelled at 22.00hrs. 2nd i/c killed, Lt. Quartermaster, Padre and Signals Officer wounded." The following day we buried the 2nd i/c and felt the terrific loss to the Regiment. Several years later through the very good services of the War Graves Commission I was able to trace and eventually visit his grave lying in peace in Bayeux cemetery.

Passing through the ruined and by now almost deserted corridor in Caen I stopped to retrieve a slightly charred but intact wall plate bearing the towns name from the still burning rubble. Somehow it had survived the crushing bombardment and would now protect it as a war souvenir. This memento I eventually carried through France, Belgium into Holland and on to the borders of Germany. Here I was lucky in a draw for U.K. leave and returned home to family bringing the wall plate for safe keeping where it continued to survive the continuing London blitz.

Sadly several years later, and happily married, my wife during a dusting session knocked it from its focal point and it broke into several pieces. I could have wept, remembering its passage through time but my good sense of humour saw the funny side of it all. Having put it together again it does have the appearance of having 'been through the wars' but still has a place of honour on my kitchen wall. Have thought over the years that I should perhaps return it to its rightful owner, but just where does one start?

Returning to the ongoing war in Europe it appeared that things were going as well as could be expected on all fronts. There were occasions when having dug a comfortable hole in the ground word would come through "we're moving again". There were no complaints as such if it was felt it brought the end of hostilities a little closer. It became a bit tough when this could happen sometimes three times in one day and with the approach of winter the earth was getting harder all the time.

It was comforting, however, to hear that the Germans were retreating down the Vire-flers road. Again my old diary reveals the path taken by the Regiment from landing in Normandy through the Altegamme on the North bank of the river Elbe, Hamburg. It gives dates and places and highlights the fact that we were forever crossing borders e.g. France into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland back into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland into Germany where we remained.

Its mobility can perhaps be made clearer in an extract from the Regtl. Citation which quotes

"The unit has been deployed almost continuously in the forward areas, and the Headquarters and Batteries have frequently been under shell and mortar fire. During this time the Regiment has not only fought in an A.A. role but has been detailed to other tasks not normally the lot of an A.A. unit. These have included frequent employment in a medium artillery role, action in an anti-tank screen, and the hasty organisation of A.A. personnel into infantry sub-units to repel enemy counter-attacks. All tasks have met with conspicuous success. The unit has responded speedily, cheerfully and efficiently to every demand made on it. The unit is one where morale is very high indeed and which can confidently be given any task".

Following the distinctive role played during the N.W. Europe campaign the Regiment was awarded a Battle Honour and its Commanding Officer a D.S.O.

Depending on the impending battle plan the various Batteries would be assigned to individual tasks i.e.

275/165 Bty u/c Gds. Armd. Div. for grd. shooting.

198/165 Bty deployed in A.A. role def. conc. area.

317/165 Bty deployed in Anti-tank role.

All tasks having been successfully completed would again move as a Regiment under command Guards Armoured Division to support a new attack.

A day to be remembered was the arrival of bread after some 40 days without. I think it only amounted to one slice per man but what a relief after nibbling on hard biscuits for so long. The men to be pitied were those with dentures who automatically soaked it in their tea or cocoa (gunfire) before consuming.

Another welcome treat was the arrival of the mobile bath and clothing unit in late August '44. It was about that time that I heard a steam whistle indicating that the railroad was back in action.

When the situation allowed a truck would take a party of men to the nearest B and C Unit which consisted of a couple of large marquee tents adjoining. In one you would completely disrobe and proceed along duck-boards to the shower area. Having enjoyed this primitive delight and dried off you would then gather vest, pants, shirt and sox then queue to be sized up by the detailed attendant in charge, to be issued with hopefully something appropriate to ones stature. It didn't always work to ones liking and caused much amusement in the changing tent where swaps occasionally took place.

The unit did however serve its purpose at the time but things became more pleasant when one could retain their own gear and could sometimes get it attended to by a local admirer.

Four moves in as many days took us into Brussels where we were given a rousing reception. Our vehicles were clambered onto from all directions by the thronging crowd, showering us with hugs and kisses, flowers, and a very brief moment to sample a glass or two or wine. No time to stop, unfortunately, and soon to depart with a small recce party en route for Nijmegan. By now things were getting slightly uncomfortable having been attacked from the air during a night in the woods and the main body of the Regiment attacked in the corridor at Veghel.

Here our guns were deployed in an Anti/tank role, field role and CB role. Several troops were provided for attack to recapture the village of Apenhoff. A tiger tank was engaged by one gun and very successful CB and concentrations fired on enemy gun areas and infantry. It was thought that casualties sustained were justified as the attack resulted in the capture of 76 prisoners, one anti-tank gun and a considerable number of enemy dead, mostly to the West of the village where most of our men finished up and where a certain amount of mortar fire was brought down upon them.

The following day the main body of the Regiment arrived in Nijmegan and were deployed in an Ack-Ack role, minus one Troop still in MTB role. It was recorded at the time that on several occasions the guns had been deployed further forward than any other guns in the Second Army and in the case of the bridge over the Escaut Canal at Overpelt it was considered that the fire provided was one of the chief factors in the bridge being captured intact.

It was during a return to Belgium for a break just before Christmas 1944 that we had the good fortune to be billeted for a few days with a wonderful family consisting of Mother and Father, six daughters and two sons. The childrens' ages ranging between possibly eighteen and three. It was the time of celebrating St. Nicholas and homely pleasures had long been forgotten as regards a roof overhead, surrounding walls, and to mix with warm and friendly people. The chance to sit at a dining table on a firm and comfortable chair, food on a plate instead of a dirty old mess-tin were simple things to be appreciated beyond words and all were saddened when it was time to return into the line.

A returning Don, R would often bring little notes written in understandable English but as the lines of communication lengthened so contact diminished.

Some 40 years later, prior to a visit to The Netherlands with a party of Normandy Veterans, I decided to write to the Burgomeister of the small village of Beverst giving him full details of the family and hoping by chance that at least one member of the large family would have survived the war and perhaps was still living in the Limburg area of Belgium.

It was beyond belief that within ten days I had a letter from the very girl, Mariette, who had sent the odd letter to me and to this day still have them in my possession. We had so much to tell each other, on her side that all her sisters were married with children, and that one of her brothers who was three years old during the war was now a priest in Louvain.

As the conducted tour at the time of visiting did not go into the Limburg area of Belgium, it was arranged that a small party from the family circle would travel by minibus and that we would hopefully meet up at a suggested time in the town of Eindhoven in Holland. There was much rejoicing when the timing was spot on and a very brief meeting with an exchange of gifts took place before it was time to clamber back onto the coach.

Over the years when visiting the Continent we meet whenever possible. I have since met all surviving members of the family, visiting their homes and meeting their children. At one of the locations a field a short distance away was pointed out to me where Hitler, a Corporal at the time, had camped during the 1914-18 war.

During one conversation I asked Mariette how the family had fared during the German occupation. She told me that on one occasion a German Officer had knocked on the door requesting the family to accommodate some German troops. The Father replied that he had eight children which he was supporting and had no room for them and luckily they departed. She went on the tell me that when the Germans were pushed out of the village and the English and the Americans moved into the area her Father gladly accepted a few English soldiers to stay, suggesting the family would double up into a couple of rooms. We still find plenty to talk about over the years when corresponding and on meeting up.

In further praise of my old Regiment it is on record that before June '44 was out, a deputation of senior officers visited the unit to learn why, and how, they were usually the first guns in the line to report "READY" and higher formations were calling for their support as a unit.

The Order of March for the operation "Garden", the Northward dash to join up with the Airborne troop was headed (1) Guards Armoured Division, (2) A.A. Group (165 H.A.A. Regt.) leading. This alone should rank a citation for the 3.7in A.A. gun. Second in the Order of March on what must be one of the most daring and spectacular assaults in history.

The 3.7s when used in their field role were fired from positions amongst the infantry and that having no gun shield the layers positions were untenable. During the closing battle for Arnhem they were able to give covering fire throughout the night withdrawal. The 3.7s with their 11 miles range were amongst the very few guns available with sufficient range to cover the flanks of the 1st Airborne at Arnhem, and for a long time there was talk of the unit being permitted to carry the honoured Pegasus on their sleeve.

It was during the withdrawal of the survivors of the Battle of Arnhem, and watching the war-torn paras filing back through Hell's Highway, that I spotted and had a quick chat with a couple of my old mates that had proudly volunteered with me on that fateful day in June '41. In a flash I though "there, but for the grace of God go I". Should I have in fact survived that horrendous and tragic battle, and where are they now I wonder?

Word that hostilities had ceased came through whilst in a little German village called Tesperhude on the North bank of the Elbe, V.E. DAY, the war in Europe had ended. Time to celebrate. All Other Ranks were invited into the Officer's mess where 'issue rum' was being served up in half-pint glasses. This was a complete change to previous issues when, during inclement weather the rum ration would have to be taken in a mug of tea. Pushing all protocol aside it was time to let our hair down and enjoy. It was suggested that a bit of music and song would be in order and the question was asked as to who could play a piano accordion. I gave up the idea of not volunteering on this special occasion and said that I could, having had some professional lessons in my youth.

A search party set off down the street and a 'squeeze box' was produced and promptly placed in position. By then the rum was taking hold and I can remember getting through two verses of "Home on the range" before collapsing over backwards to a cacophony of sound as the bellows extended across my chest. Can't say the C.O. and other Officers were too pleased with the musical performance and I felt the effects of the vapours for a few days following. I made up my mind there and then that I never wished to experience the taste of Nelson's blood ever again, as I also felt about the thought of never wishing to see spam and bully beef, but time is a great healer?

Release from the service being on an 'Age and Service' basis meant that I possibly had another year or so to serve before being discharged. I would have been more than content to remain in the area of Hamburg until my release papers arrived, but unfortunately it was not to be. An urgent War Office posting, I was told, brought me back to England and a spell at Woolwich Barracks which I found most discouraging and ungratifying.

I was to join a newly formed contingent of mostly new recruits about to depart for the Far East, by mid November '45 I was on a troopship bound for Bombay. Christmas 1945 was spent in the Royal Artillery Transit Camp at Deolali where I spent a few weeks before entraining and travelling across India to Calcutta. It wasn't quite the Orient Express for comfort and cuisine, and I can remember being fired upon by rampaging dacoits at one point.

Several more weeks were spent in a transit camp in Calcutta experiencing all the delights of Chowringee and thereabouts – felt quite the pukka sahib at times before word came through that we would be sailing for Rangoon the following day.

Going aboard the S.S 'City of Canterbury' there was the usual rush for hammocks and best positions on deck. Arriving in Rangoon I was happy to receive my first letter from home in seven weeks and was a relief to be sure. I had still not reached journeys end and it was not until mid February 1946 that I joined my intended unit, a Field Regiment, on the borders of Mandalay in Burma.

I was finally homeward bound by the late summer of '46 to enjoy three months overseas leave and a return to civilian life.

Looking back over the years in the forces there were some good times and some exceedingly bad times but having come through it all reasonably fit and healthy I feel the WAR YEARS have shown me the true value of life and that, in retrospect, I feel proud not to have missed this experience of a lifetime.

Written in March 1994.

Contributed originally by vegetop (BBC WW2 People's War)

My first memory goes back to the night when the docks were bombed with incendiary bombs and the whole sky was lit up.

My parents and I were walking our dog when the siren sounded and we turned to go back home. Immediately after the siren, we heard the German planes overhead and then, when we were almost home, there was a shrill screaming sound which was getting louder and louder. My father shouted; "It's a bomb" and we all ran as fast as we could to our front door, and as Dad fumbled for the key and opened the door, the screaming sound seemed to be chasing after us and we all fell into the hall in a heap. Then followed a tremendous explosion. The bomb fell not far from our home. My father gave me some sips of brandy to get over the shock. It was my first experience of a bomb and that kind of bomb, a screaming bomb was meant to terrify you.

I remember my mother putting up the thick black curtains at our windows to stop any light showing on the outside and my father putting sticky brown tape across the windows to protect them from bomb blasts.

At night everywhere was pitch black. No lights of any kind were allowed. We had a torch, which had a shade over the top so that it didn't shine upwards.

All the schools in London closed, and most children were evacuated. My mother didn't want me to go, so I stayed on in London. I didn't go to school for a whole year. Then one of our French teachers came back to London and she started giving French lessons at her home.

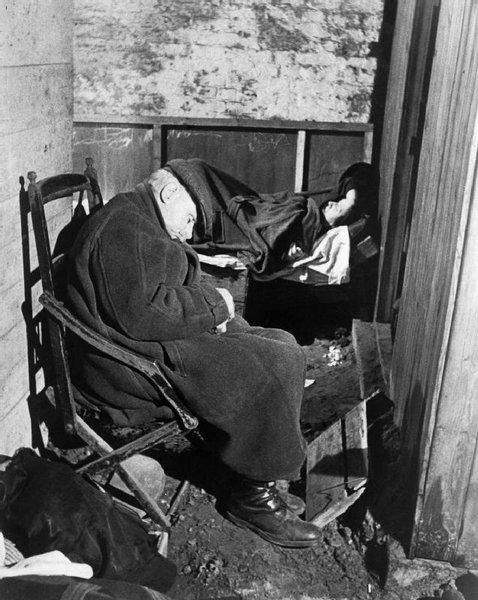

We lived in an upstairs maisonette, and during the blitz we spent every night huddled under our dining room table to get some protection if the roof fell in. I used to get stomach cramps from crouching under there for so long. Later we started sheltering, with our downstairs neighbours, in the cupboard under their stairs.

Eventually, brick shelters were built in the road with bunk beds in them. Each night at dusk when the sirens sounded, we made our way to the shelter with our blankets. I recall that the shelter had a leaky roof and, if you slept on a top bunk, you had to put up an umbrella if it rained.

My father was in the Police and was stationed in Clapham where we lived. He used to work four weeks at a time on night duty. Mum and I always worried for his safety as the bombs fell. There was also the danger of being hit by shrapnel from the four big guns on Clapham Common.

The noise was unbelievable with the sound of the aeroplanes, the bombs, and the gunfire, which shook our house. After one air raid, when we came back in the morning from the air raid shelter, we found a hole in the roof. A lump of shrapnel had come through and was embedded in the seat of my father's armchair!

The next day, after the night raids, I often went out picking up shrapnel from the streets.

My father would come home with awful tales of his rescue work. I think he needed to talk about it to relieve his stress. One night, when a bomb had fallen quite close to us, he told us that they had been taking arms and legs out of the trees.

He would come home with burned out incendiary bombs for us to see, and he had cut a cord off the parachute of a de-fused land mine and brought that home.

When the London blitz was on the siren would sound every night as dusk fell. It was a sound that tied one's stomach in knots with fear.

One night when Mum and I were crouched under the table, we heard a crash as something hit our guttering. We fled downstairs terrified, and when we opened the front door the whole street was lit up with houses on fire from incendiary bombs. The one which had hit our guttering had luckily bounced off into the garden.

During these raids there was also the constant worry that there would be a gas attack and so, of course, your gas mask went with you everywhere and we would often put it on to practise using it. I remember being very upset because my dog had not got a gas mask and I decided he would perhaps be protected if I put him in my wardrobe during a gas attack. I put a blanket in there and hoped the door was a tight enough fit to stop any gas getting in.

In the next road a large empty house had been taken over by the bomb disposal squad, known as the "suicide squad". The garden of the house was full of de-fused bombs and land mines.

As I said earlier, I had no school to go to for a year during the heavy raids, but when things quietened down a little St. Martins in the Fields High School opened up in Tulse Hill. It was a fee-paying school, but I and four other children in the area were told to go there. As we were scholarship children we were the only children whose parents did not pay fees, which made me feel a bit of an outcast. I was there for over a year.

Then my old school was opened under the new name of South West London Emergency Secondary School and all the children from quite a large area who had not been evacuated went there. I was then fourteen years old.

To get to school I had to cycle across Clapham Common past those four big guns. I used to pray that there would not be an air raid when I was anywhere near them.

The memory of the school dinners remains to this day. Mainly we had salads consisting of grated raw cabbage, raw turnips, carrots and dried potatoes; and at almost every meal the pudding was semolina and jam!

When the sirens sounded we had to go to the sandbagged cloakrooms.

During this time another empty school in Clapham had become a billet for French sailors. On our way home from school my friend and I used to chat to them to try out our French.

American soldiers occupied a small block of flats near the common and several times we spotted one of our teachers on the arm of one of them.

Everyone had allotments at that time to "dig for victory" and part of the common had been allocated for allotments.

My father had one, and my friend and I took one on. We had to dig up the turf first which was a hard job. We worked on the allotment after school and at weekends.

Homework was quite a problem. Many times during air raids I sat on the doorstep doing it until the German planes were overhead, and then I would dash into the shelter.

One night a bomb fell in the High Road between Clapham South and Balham Underground stations making a huge crater. A bus came along and fell into the hole.

That was bad enough, but even worse, the bomb had penetrated the underground tube which ran along under the road and also burst the water main. The water flooded the Underground between the two stations drowning hundreds of people who were sleeping on the platforms believing it to be very safe down there.

My father helped in the rescue operation and bodies were being brought out for weeks afterwards.

My father had tried to persuade my mother to spend our nights on the Underground platforms. I wouldn't be here today if I had!

Later came the flying bombs also known as "buzzbombs" or "doodlebugs".

My first experience of bomb blast happened when I was walking down Balham High Road one day with friends. I looked up and saw a flying bomb above us. We prayed the engine would not cut out. It did, and it started to dive towards us. We flung ourselves flat on the ground and waited for the explosion. It landed very close by and the blast took my breath away, and glass was flying everywhere from the shop windows.

We took our School Certificate or Matriculation, as it was known in those days, during these attacks. We had desks lined up in the aisles of the sandbagged cloakrooms and we did all our exams in there.

It was very hard to concentrate. When the siren had sounded you were listening for the droning sound of a flying bomb and hoping it would pass over. The wait seemed interminable, hoping the engine wouldn't cut out. While writing one of my exams there was a tremendous explosion and my pen went right across the page crossing out all I had written. Afterwards there was the extra worry that my home could have been hit - and were my mother and father safe?

I don't think anyone passed those exams, not surprising under the circumstances!

I won a music scholarship and moved on to the sixth form at Mary Datchelor School in Camberwell where I re-sat the School Certificate exams & was successful that time because things were a bit quieter then.

At about this time the V2 rockets started falling. There was no warning with them so life had to go on with the terrible fear always with you that at any time one could fall on you or your family.

There was one outstanding occasion when, before coming home from school, we had heard a big explosion. When I got off the bus and started walking home there was broken glass and debris along the streets and the nearer I got to home there was more and more debris and damage. I dreaded turning the last corner in case it was our home that had been hit and I knew my mother would have been at home. Luckily we escaped with just blast damage.

Then came VE day. I think I was at school when it was announced that the war in Europe had ended.

We didn't have any street parties but what excitement and mainly relief that all our worries were over at last.