High Explosive Bomb at Brixton Road

Description

High Explosive Bomb :

Source: 24 hours of Blitz Sept 7th 1940

Fell on Sept. 7, 1940, at 9:51 p.m.

Present-day address

Brixton Road, Stockwell, London Borough of Lambeth, SW9 0AR, London

Further details

Brixton Road, Brixton SW9, London, UK ; South Met Gas. 4"" main fractured

Nearby Memories

Read people's stories relating to this area:

Contributed originally by kenyaines (BBC WW2 People's War)

After a few months of the tortuous daily Bus journey to Colfes Grammar School at Lewisham, I'd saved enough money to buy myself a new bicycle with the extra pocket money I got from Dad for helping in the shop.

Strictly speaking, it wasn't a new one, as these were unobtainable during the War, but the old boy in our local Cycle-Shop had some good second-hand frames, and he was still able to get Parts, so he made me up a nice Bike, Racing Handlebars, Three-Speed Gears, Dynamo Lighting and all.

I was very proud of my new Bike, and cycled to School every day once I'd got it, saving Mum the Bus-fare and never being late again.

I had a good friend called Sydney who I'd known since we were both small boys. He had a Bike too, and we would go out riding together in the evenings.

One Warm Sunday in the Early Summer, we went out for the day. Our idea was to cycle down the A20 and picnic at Wrotham Hill, A well known Kent beauty spot with views for miles over the Weald.

All went well until we reached the "Bull and Birchwood" Hotel at Farningham, where we found a rope stretched across the road, and a Policeman in attendance. He said that the other side of the rope was a restricted area and we couldn't go any further.

This was 1942, and we had no idea that road travel was restricted. Perhaps there was still a risk of Invasion. I do know that Dover and the other Coastal Towns were under bombardment from heavy Guns across the Channel throughout the War.

Anyway, we turned back and found a Transport Cafe open just outside Sidcup, which seemed to be a meeting place for cyclists.

We spent a pleasant hour there, then got on our bikes, stopping at the Woods on the way to pick some Bluebells to take home, just to prove we'd been to the Country.

In the Woods, we were surprised to meet two girls of our own age who lived near us, and who we knew slightly. They were out for a Cycle ride, and picking Bluebells too, so we all rode home together, showing off to one another, but we never saw the Girls again, I think we were all too young and shy to make any advances.

A while later, Sid suggested that we put our ages up and join the ARP. They wanted part-time Volunteers, he said.

This sounded exciting, but I was a bit apprehensive. I knew that I looked older than my years, but due to School rules, I'd only just started wearing long trousers, and feared that someone who knew my age might recognise me.

Sid told me that his cousin, the same age as us, was a Messenger, and they hadn't checked on his age, so I went along with it. As it turned out, they were glad to have us.

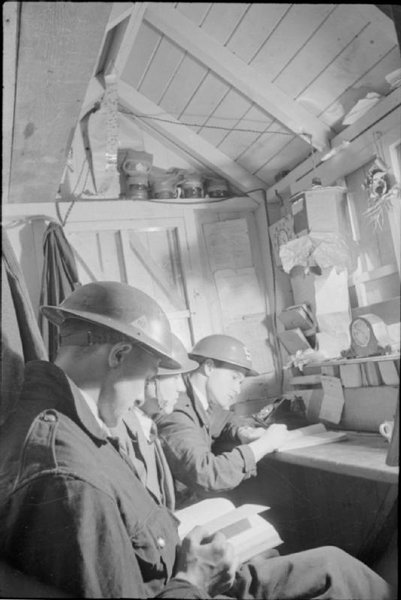

The ARP Post was in the Crypt of the local Church, where I,d gone every week before the war as a member of the Wolf-Cubs.

However, things were pretty quiet, and the ARP got boring after a while, there weren't many Alerts. We never did get our Uniforms, just a Tin-Hat, Service Gas-Mask, an Arm-band and a Badge.

We learnt how to use a Stirrup-Pump and to recognise anti-personnel bombs, that was about it.

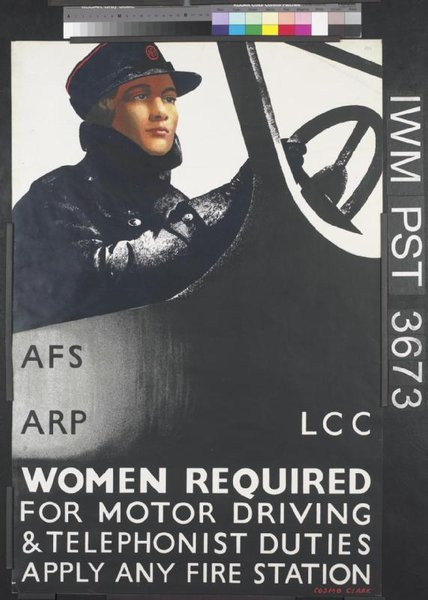

In 1943, we heard that the National Fire Service was recruiting Youth Messengers.

This sounded much more exciting, as we thought we might get the chance to ride on a Fire-Engine, also the Uniform was a big attraction.

The NFS had recently been formed by combining the AFS with the Local and County Fire Brigades throughout the Country, making one National Force with a unified Chain of Command from Headquarters at Lambeth.

The nearest Fire-Station that we knew of was the old London Fire Brigade Station in Old Kent Road near "The Dun Cow" Pub, a well-known landmark.

With the ARP now behind us,we rode down there on our Bikes one evening to find out the gen.

The doors were all closed, but there was a large Bell-push on the Side-Door. I plucked up courage and pressed it.

The door was opened by a Firewoman, who seemed friendly enough. She told us that they had no Messengers there, but she'd ring up Divisional HQ to find out how we should go about getting details of the Service.

This Lady, who we got to know quite well when we were posted to the Station, was known as "Nobby", her surname being Clark.

She was one of the Watch-Room Staff who operated the big "Gamel" Set. This was connected to the Street Fire-Alarms, placed at strategic points all over the Station district or "Ground", as it was known. With the info from this or a call by telephone, they would "Ring the Bells down," and direct the Appliances to where they were needed when there was an alarm.

Nobby was also to figure in some dramatic events that took place on the night before the Official VE day in May 1945 when we held our own Victory Celebrations at the Fire-Station. But more of that at the end of my story.

She led us in to a corridor lined with white glazed tiles, and told us to wait, then went through a half-glass door into the Watch-Room on the right.

We saw her speak to another Firewoman with red Flashes on her shoulders, then go to the telephone.

In front of us was another half-glass door, which led into the main garage area of the Station. Through this, we could see two open Fire-Engines. One with ladders, and the other carrying a Fire-Escape with big Cart-wheels.

We knew that the Appliances had once been all red and polished brass, but they were now a matt greenish colour, even the big brass fire-bells, had been painted over.

As we peered through the glass, I spied a shiny steel pole with a red rubber mat on the floor round it over in the corner. The Firemen slid down this from the Rooms above to answer a call. I hardly dared hope that I'd be able to slide down it one day.

Soon Nobby was back. She told us that the Section-Leader who was organising the Youth Messenger Service for the Division was Mr Sims, who was stationed at Dulwich, and we'd have to get in touch with him.

She said he was at Peckham Fire Station, that evening, and we could go and see him there if we wished.

Peckham was only a couple of miles away, so we were away on our bikes, and got there in no time.

From what I remember of it, Peckham Fire Station was a more ornate building than Old Kent Road, and had a larger yard at the back.

Section-Leader Sims was a nice chap, he explained all about the NFS Messenger Service, and told us to report to him at Dulwich the following evening to fill in the forms and join if we still wanted to.

We couldn't wait of course, and although it was a long bike ride, were there bright and early next evening.

The signing-up over without any difficulty about our ages, Mr Sims showed us round the Station, and we spent the evening learning how the country was divided into Fire Areas and Divisions under the NFS, as well as looking over the Appliances.

To our delight, he told us that we'd be posted to Old Kent Road once they'd appointed someone to be I/C Messengers there. However, for the first couple of weeks, our evenings were spent at Dulwich, doing a bit of training, during which time we were kitted out with Uniforms.

To our disappointment, we didn't get the same suit as the Firemen with a double row of silver buttons on the Jacket.

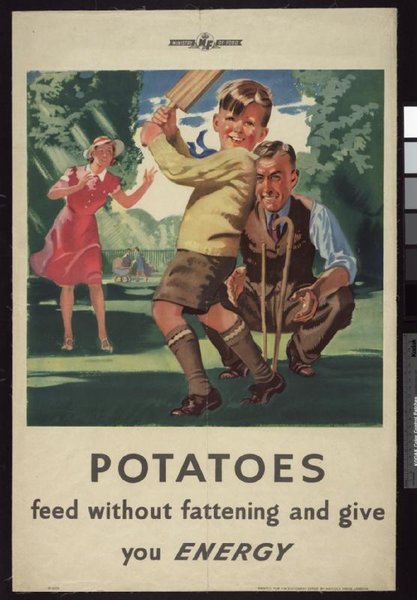

The Messenger's Uniform consisted of a navy-blue Battledress with red Badges and Lanyard, topped by a stiff-peaked Cap with red piping and metal NFS Badge, the same as the Firemen's. We also got a Cape and Leggings for bad weather on our Bikes, and a proper Service Gas-Mask and Tin-Hat with NFS Badge transfer.

I was pleased with it. I could definitely pass for an older Lad now, and it was a cut above what the ARP got.

We were soon told that a Fireman had been appointed in charge of us at Old Kent Road, and we were posted there. After this, I didn't see much of Section-Leader Sims till the end of the War, when we were stood down.

Old Kent Road, or 82, it's former LFB Sstation number, as the old hands still called it,was the HQ Station of the District, or Sub-Division.

It's full designation was 38A3Z, 38 being the Fire Area, A the Division, 3 the Sub-Division, and Z the Station.

The letter Z denoted the Sub-Division HQ, the main Fire Station. It was always first on call, as Life-saving Appliances were kept there.

There were several Sub-Stations in Schools around the Sub-Division, each with it's own Identification Letter, housing Appliances and Staff which could be called upon when needed.

In Charge of us at Old Kent Road was an elderly part-time Fireman, Mr Harland, known as Charlie. He was a decent old Boy who'd spent many years in the Indian Army, and he would often use Indian words when he was talking.

The first thing he showed us was how to slide down the pole from upstairs without burning our fingers.

For the first few weeks, Sid and I were the only Messengers there, and it was a very exciting moment for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump for the first time when the bells went down.

In his lectures, Charlie emphasised that the first duty of the Fire-Service was to save life, and not fighting fires as we thought.

Everything was geared to this purpose, and once the vehicle carrying life-saving equipment left the Station, another from the next Station in our Division with the gear, would act as back-up and answer the next call on our ground.

This arrangement went right up the chain of Command to Headquarters at Lambeth, where the most modern equipment was kept.

When learning about the chain of command, one thing that struck me as rather odd was the fact that the NFS chief at Lambeth was named Commander Firebrace. With a name like that, he must have been destined for the job. Anyway, Charlie kept a straight face when he told us about him.

We had the old pre-war "Dennis" Fire-Engines at our Station, comprising a Pump, with ladders and equipment, and a Pump-Escape, which carried a mobile Fire-Escape with a long extending ladder.

This could be manhandled into position on it's big Cartwheels.

Both Fire-Engines had open Cabs and big brass bells, which had been painted over.

The Crew rode on the outside of these machines, hanging on to the handrail with one hand as they put on their gear, while the Company Officer stood up in the open cab beside the Driver, lustily ringing the bell.

It was a never to be forgotten experience for me to slide down the pole and ride the Pump in answer to an alarm call, and it always gave me a thrill, but after a while, it became just routine and I took it in my stride, becoming just as fatalistic as the Firemen when our evening activities were interrupted by a false alarm.

It was my job to attend the Company Officer at an incident, and to act as his Messenger. There were no Walkie-Talkies or Mobile Phones in those days, and the public telephones were unreliable, because of Air-Raids, that's why they needed Messengers.

Young as I was, I really took to the Fire-Service, and got on so well, that after a few months, I was promoted to Leading-Messenger, which meant that I had a stripe and helped to train the other Lads.

It didn't make any difference financially though, as we were all unpaid Volunteers.

We were all part-timers, and Rostered to do so many hours a week, but in practice, we went in every night when the raids were on, and sometimes daytimes at weekends.

For the first few months there weren't many Air-Raids, and not many real emergencies.

Usually two or three calls a night, sometimes to a chimney fire or other small domestic incident, but mostly they were false alarms, where vandals broke the glass on the Street-Alarms, pulled the lever and ran. These were logged as "False Alarm Malicious", and were a thorn in the side of the Fire-Service, as every call had to be answered.

Our evenings were good fun sometimes, the Firemen had formed a small Jazz band.

They held a weekly Dance in the Hall at one of the Sub-Stations, which had been a School.

There was also a full-sized Billiard Table in there on which I learnt to play, with one disaster when I caught the table with my cue, and nearly ripped the cloth!

Unfortunately, that School, a nice modern building, was hit by a Doodle-Bug later in the War, and had to be demolished.

Charlie was a droll old chap. He was good at making up nicknames. There was one Messenger who never had any money, and spent his time sponging Cigarettes and free cups of tea off the unwary.

Charlie referred to him as "Washer". When I asked him why, the answer came: "Cos he's always on the Tap".

Another chap named Frankie Sycamore was "Wabash" to all and sundry, after a song in the Rita Hayworth Musical Film that was showing at the time. It contained the words:

"Neath the Sycamores the Candlelights are gleaming, On the banks of the Wabash far away".

Poor old Frankie, he was a bit of a Joker himself.

When he was expecting his Call-up Papers for the Army, he got a bit bomb-happy and made up this song, which he'd sing within earshot of Charlie to the tune of "When this Wicked War is Over":

Don't be angry with me Charlie,

Don't chuck me out the Station Door!

I don't want no more old blarney,

I just want Dorothy Lamour".

Before long, this song was taken up by all of us, and became the Messengers Anthem.

But this little interlude in our lives was just another calm before another storm. Regular air-raids were to start again as the darker evenings came with Autumn and the "Little Blitz" got under way.

To be continued.

Contributed originally by Berylsdad (BBC WW2 People's War)

BRAVERY

In those early days of the Blitz, there were many unsung heroes who, by their personal conduct and fervent belief that we could beat the menace of Hitler’s frightfulness, inspired us to carry on and keep London working. So little has been recorded of how this threat to our great city was successfully combated by the ordinary man in the street. As a nation, we are chary of patting ourselves on the back and it is, perhaps, for that reason, that the bravery of so many has been recognised by so few.

Amongst the unsung heroes, there will always remain in my memory a comrade by the name of Edward Bennett of Lyndhurst Way, Camberwell, affectionately known to members of the Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot as “Pop”. It was this oft-blitzed depot that the late Vivian Woodward served and Ted Heming learned first-aid and rescue work that was later to help him to win his George Cross. Cambridge University students also did relief work there and, as a tribute to the staff, afterwards entertained our Depot’s cricket team at Cambridge, where Vivian probably played his last cricket match and Ted was included in the team.

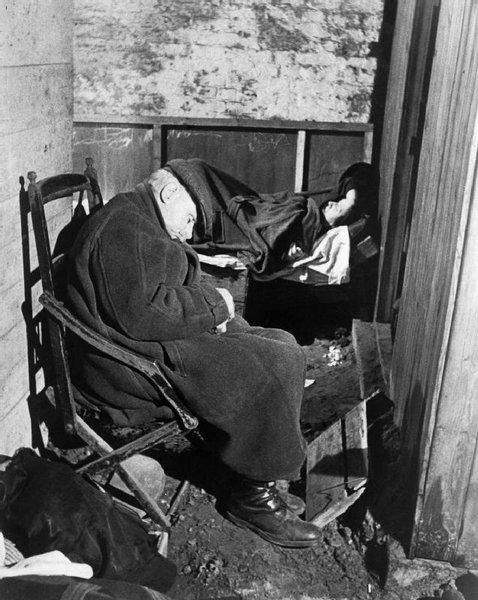

Our “Pop” was nearly sixty years of age when he joined the Civil Defence, his duties covering the period of 24 hours on and 24 hours off. But when the Blitz on London started, Pop, like many others, voluntarily became ‘on-call’ on his off-duty nights and therefore available to fill any gap that might occur in the on-duty ranks. This often meant continual work over thirty-six hour periods. During those hectic days and nights, Pop, if not require for any other duty, would take up position in an ordinary unprotected Sentry Box, situated just outside the Depot, and keep fire-watch whilst indulging in a humorous commentary upon the way “Jerry” was “getting it” in the battle raging overhead. Despite many requests from his friends to take advantage of cover, Pop would still carry on. There is no doubt that his humour and sangfroid did much to raise the morale of his team-mates in those early days. One night, when Pop was out at an incident, the Sentry Box was blown to smithereens by a bomb exploding just outside the Depot. But, box or no box, Pop still continued, in his spare moments, to stand in the same position and his lively commentaries remained unabated. His devotion to duty was tremendous and it is due to this fact that we lost an untiring and heroic figure. The responsibility for his passing lies primarily with the dropping of a large enemy bomb, but the chemical deposits in Mother Earth subscribed in a mysterious way to our loss.

On 4th October, 1940, when Pop was officially off-duty, he reported as usual as being available ‘on-call’. After a quiet beginning to that fateful night, Camberwell soon received its usual strafing. Amongst the quota was a heavy HE bomb that dropped in a garden close to our Depot. The action of the bomb was weird in effect, for although it penetrates the earth very deeply, throwing tons of clay into the adjoining streets, and the explosion severely blasted surrounding houses, there was little sign of a crater, the point of impact only being marked by a ring of fire on the surface of the ground that afterwards was recognised by the experts as due to the ignition of subterranean gases. Some minutes elapsed before Headquarters assigned one of our Parties to cover the incident, but Pop, not bound by the necessity of awaiting an official order, had dashed round to the spot to see if his first-aid qualifications were needed. Happily, except for a few slight shock cases, no-one was injured, but a number of women in nearby Anderson shelters were pleading for the flames, that were now reaching considerable proportions, to be extinguished. At that stage of the Blitz, most people, influenced no doubt by the Official Lighting Order, regarded ground lights of any nature as a greater menace to safety than any danger that existed in the battle raging overhead. The first-aid Party sent from our Depot arrived on the scene to find Pop endeavouring to smother the flames with earth. As they approached, they almost immediately felt themselves being drawn as if by magnetic forces towards the spot from which Pop was operating. Flinging themselves to the ground, they just managed to evade being sucked into the centre of the flames. When they picked themselves up some moments later, the fire had partly subsided, but Pop and a valiant helper had vanished, without a cry or any indication of distress, into the bowels of the earth. Despite frenzied digging by his comrades that night and subsequent weeks of endless toil by specialised rescue teams, not a single particle of clothing or equipment or clue to their whereabouts was then or since discovered. The official theory was that Pop and his friend were drawn by suction down to a subterranean stream for, although powerful pumps were employed, water at 20 feet made further excavation work impossible.

But, though Pop vanished beyond our ken, he will ever remain in the hearts of all who served at Bellenden Road, as a very gallant and unsung hero.

C R Mercer

Superintendent, Bellenden Road Stretcher Party Depot

Contributed originally by 2nd Air Division Memorial Library (BBC WW2 People's War)

This story was submitted to the People's War site by Jenny Christian of the 2nd Air Division Memorial Library in conjunction with BBC Radio Norfolk on behalf of Frank L Scott and has been added to the site with his permission. The author fully understands the site's terms and conditions.

Part one

I was eighteen, going on nineteen, when the storm clouds of war started to gather. Life was good ; a happy home, loving and devoted parents and family, sound job prospects and a variety of interesting hobbies and out-door pursuits. All this adding up to an enjoyable and hopefully peaceful future. Life was indeed worth living!

My dreams were shattered on that morning in early September 1939 when the sirens sounded throughout the land warning 'Englanders' of an immediate air attack when the suspected might of the German Luftwaffe would rain down upon us.

Most people that could, and were able, ran for cover long before the mournful wail of the penetrating sound of the air-raid sirens had faded away.

My family consisting of Mother and Father, two sisters, three younger brothers and an elderly Grandfather took to our heels and made for the conveniently placed 'Anderson' shelter dug into the back garden. I can't remember the exact measurements of that particular type, but I do know that to house nine adults for any length of time, as it eventually did for several months to come, has to be experienced to be believed. Not only was it very uncomfortable in such a confined space but there was always a fear of the unknown horrors of bombing raids.

Within the shelter, there was the cheerful chatter to keep up our spirits but outside there was an uncanny silence which was broken some time later by the ALL CLEAR signal. A sound we got to love and hear. Nothing happened that particular day and we remained unscathed.

The sound of that very first warning at about 11 o'clock on Sunday 3rd September 1939 will long remain in the memories of many folk, the elderly and not so young, and was a discord we all learnt to live with and to rejoice endlessly to the welcome sound of the ALL CLEAR.

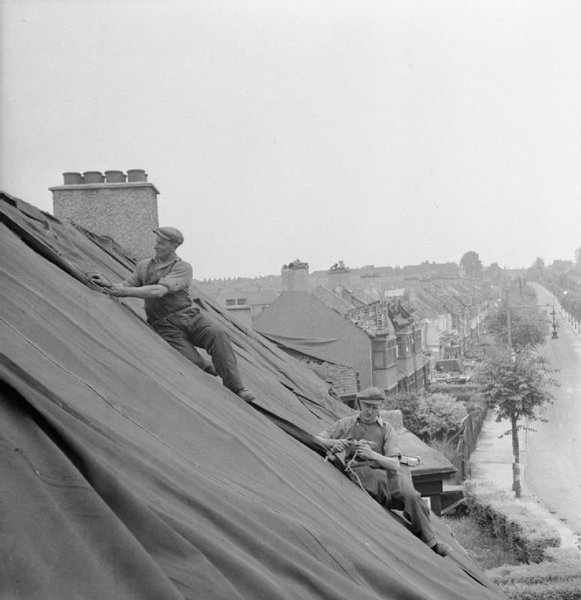

This situation continued for many months with warnings of imminent raids which came to nothing. So began the 'phoney war' as it became to be known. Because of the continuous interruptions caused daily when enemy aircraft were unable to penetrate the air defences, spotters were placed on rooftops of factories, offices, power stations etc., to warn workers only when there were signs of impending danger.

Unfortunately, this was rather short lived and many large towns and cities suffered badly when the German High Command decided to step up and concentrate on a more devastating and annihilating blow, in particular to the civilian population.

My personal experience of this period of time was when taking a girlfriend to a cinema in Elephant and Castle area of London and to be informed by the Manager of the cinema that a heavy bombing raid was taking place in the dock area of the East End. Not that that had much significance to a couple in the back row, who continued there until the bombing got worse and the Manager informed those remaining that the cinema was about to close.

Most people that were able to went underground that evening and it wasn't until the ALL CLEAR sounded in the early morning at daylight that they came out again and went about their business.

Living not far from this area, my first thoughts were for my family and I wished to check on their welfare as soon as possible. Because of the ferocity of the raid, there was much local damage and fires were raging everywhere, accounting for endless lengths of firemans' hosepipes to be trampled over in search of public transport which, by that time, was non-existent. Having escorted my girlfriend home which, unfortunately, was in the opposite direction to the one I would have wished to get me home quickly, but eventually I made it and found them safe and sound. A block of flats nearby had taken a direct hit during the raid.

This signalled the beginning of endless night after night bombing raids on London and 'Wailing Willie' would sound without fail at dusk about the time that mother would be putting the finishing touches to the picnic basket that the family trundled to the garden air-raid shelter. Not too often, but some nights for a change of scenery, or further company, we would go to a communal shelter but must admit that we all felt most secure at 'ours'.

So, life went on, come what may, raids or no raids. All went of to work the next morning trusting and hoping that our work place would still be there. Battered or not, running repairs would be performed and it would be 'business as usual'.

My father, being in the newspaper distribution trade and a night worker would clamber out of the shelter in the early hours but would return occasionally during the night to see that all was well. He would also drop in the morning papers which were often read beneath the glow of the searchlight beams raking the darkened sky in search of enemy aircraft. An additional item on one particular raid was when a nearby gasometer near the Oval cricket ground was hit and a whole cascade of aluminium flakes came drifting down in the light of the search light beams.

Being in 'Civvy Street' at that time, and in what was considered a reserved occupation with a company of manufacturing chemists, my only contact with the war and ongoing battles in various theatres of war was through the press. It was not until that little brown envelope appropriately marked O.H.M.S. fell through the letter-box did my involvement with the military begin.

"You will report" it began, and so I did to the local Labour exchange when it set the ball rolling with regard to medicals, which arm of the service, date of call up etc. I also remember that my company deducted my pay that day. Something I never forgave them for and therefore had no wish to rejoin them on release from the forces.

Came the day, or rather it very nearly didn't! One of the most frightening and devastating attacks on London came that night. The railway station that I had to report to for transport to camp had been put out of action and I can remember clearly seeing passenger carriages hanging onto the roads from railway bridges. Plan 'B' was immediately put into operation and road transport was made available to take us "rookies" to the next station down the line.

The Military Training Camp on the borders of Salisbury Plain became home for the next six weeks when one went through all the motions of becoming a fighting soldier, with discipline and turn-out being the Order of the Day. Whatever one says about Training Sergeants I think our Squad must have struck lucky because we decided to have a whip round and buy him a parting gift before our leaving camp and being drafted to a searchlight mob. Thus ended basic training in the Royal Artillery.

The next venue was over the border; a searchlight training camp on the West coast of Scotland. Within a very short time and very little action, boredom set in and a Regimental office notice calling for volunteers for Airborne Divisions prompted a few of my mates and I to put our names forward. Knowing the outcome of some of their eventual encounters in later battles I am thankful now that an earlier posting took me to a newly formed Heavy Anti-Aircraft Regiment of which I am justly proud.

Whilst serving with a searchlight Battery Headquarters in Suffolk, apart from the usual flak and hostile fire being an every day occurrence, Cupid's dart took a hand when the A.T.S. became part of the Establishment and a cute little red-head arrived on site. A war-time romance followed but a further posting from that unit took me to another part of the country. As the saying goes "Love will find a way" and it did for we kept in touch until distance and timing took its toll. That was over 50 years ago and through a twist of fate, a news item that appeared in a national newspaper put us in touch again.

My Regiment, the 165 H.A.A. Regt. R.A. with the fully mobile 3.7in gun had many different locations during the build up to D Day but it was fortunate enough to complete its full mobilisation for overseas service in a pleasant area on the outskirts of London. This suited me fine as it was but a short train journey to my home and providing there was no call to duty I would take the opportunity of going A.W.O.L. and dropping in on my folks for a chat and a pint at the local. However, I always made a point of getting back in time for reveille and no one was the wiser. It was also decided about that time that every man in the Regiment should be able to drive a vehicle before proceeding overseas so that was another means of getting up town for a period of time.

Inevitably all good things come to an end and we received our "Marching Orders" to proceed in convoy to the London Docks. The weather at that time was worsening putting all the best laid plans 'on hold'. Although restrictions as regards personnel movements were pretty tight some local leave was allowed. It would have been possible for me to see my folks just once more before heading into the unknown but having said my farewells earlier felt I just couldn't go through that again.

Part Two

With the enormous numbers of vehicles and military equipment arriving in the marshalling area and a continuous downpour of rain it wasn't long before we were living in a sea of mud and getting a foretaste of things to come.

To idle away the hours whilst awaiting to hear the shout "WE GO", time was spent playing cards (for the last remaining bits of English currency), much idle gossip, and I would suspect thinking about those we were leaving behind. God knows when, or if, we would be seeing them again. By now this island we were about to leave, with its incessant Luftwaffe bombing raids and the arrival of the 'Flying Bomb', had by now become a 'front line' and it was good to be thinking that we were now going to do something about it !!

All preparations were made for the 'off'. Pay Parade and an issue of 200 French francs (invasion style), and then to 'Fall In' again for an issue of the 24hr ration pack (army style), vomit bags and a Mae West (American style). Just time to write a quick farewell letter home before boarding a troopship.

Very soon it was 'anchors away' and I think I must have dozed off about that point for I awoke to find we were hugging the English coast and were about to change course off the Isle of Wight where we joined the great armada of ships of all shapes and sizes.

It wasn't too long before the coastline of the French coast became visible, although I did keep looking over my shoulder for the last glimpse of my homeland. The whole sea-scape by now being filled with an endless procession of vessels carrying their cargos of fighting men, the artillery, tanks, plus all the other essentials to feed the hungry war machine.

The exact role of my particular arm of the Royal Artillery was for the Ack-Ack protection of air-fields and consisted of Headquarters and three Batteries, each Battery having two Troops of four 3.7in guns, totalling some 24 guns in all. This role was to change dramatically as we were soon to discover. In the Order of Battle we would not therefore be called into action until a foothold had been successfully gained and position firmly held in NORMANDY.

The first night at sea was spent laying just off the coast at Arromanches (Gold Beach) where some enemy air activity was experienced and a ship moored alongside unfortunately got a H.E. bomb in its hold. Orders came through to disembark and unloading continued until darkness fell. An exercise that had no doubt been overlooked and therefore not covered during previous years of intensive training was actually climbing down the side of a high-sided troopship in order to get aboard, in my case, and American LCT.

This accomplished safely, with every possible chance of falling between both vessels tossing in a heaving sea, there followed a warm "Welcome Aboard" from a young cheerful freshfaced, gum chewing, cigar smoking Yank. I believe I sensed the smell of coffee and do'nuts!!

Making sure that the assigned vehicle for my entry into Normandy and beyond was loaded aboard I settled down, anticipating WHAT, but surveying the panoramic view as we approached the sandy shore by now littered with the remains of the earlier major onslaught.

Undoubtedly one couldn't have been too aware of the incoming and outgoing tides as the water was far too deep at the beach-head and found it necessary to cruise around until late into the evening before it was decided to make for the shore come what may!! By then it was time to join the other members of the regiment's advance party in the Humber staff car which included driver, a radio operator, the C.O. and Adjutant.

Following the dropping of the anchor, the loading ramp was immediately lowered to the accompaniment of the sound of the engines breaking into life. I think at that point the two officers became aware that we were still in 'deep water' for they decided to climb onto to roof of the 'Z' vehicle as it proceeded down the ramp. In spite of seeing the sea water gradually climbing half way up the windscreen the O.Rs feet remained reasonably dry and we made the shore with the aid of the four-wheel drive.

At the first peaceful opportunity it was essential to shed the vehicle of its waterproofing materials and extend the exhaust pipe. The canvas parts of this exercise I decided to keep, as I thought that they would be useful (time permitting) for lining ones fox-hole, which I later found to be ideal.

My ancient tatty looking 1944 diary informs me that I slept in a field and awoke at 05.30hrs to a glorious sunny day, that I washed in a stream,sampled my 24hr ration pack, saw my first dead jerry and that General De Gaulle passed the Assembly Point.

I must admit that without the aid of my diary that I managed to keep throughout the war (something that I could have been very severely reprimanded for had it been known at the time) and the treasured letters that my Mother retained until her dying day, I could not possibly remember all the most intimate details of my soldiering days.

Returning to those early entries, whilst enjoying the pleasure of a quick splash in a neighbouring stream I became aware of some girlish giggling in the adjoining bushes and felt that this was an early indication that the natives were friendly.

We proceeded inland, the Sappers having done their stuff and prepared safe lanes amid endless rows of tape with the deathly skull and crossbones indicating ACHTUNG MINEN, it was decided to set up Regimental H.Q. in the area of Beny-sur-mer.

During a check halt en route I noticed that a small area of corn a few yards into a vast cornfield had been disturbed. Taking a chance and feeling inquisitive I decided to investigate. And there it was the ENEMY, but proved not to be too much of a problem. How long he had been there I do not know. He was lying on his back, his feet heavily bandaged no doubt through endless marching, his Jack Boots placed beside his body. I also notice hurriedly that his ring finger was missing? Someone's Son, someone's Father, someone's brother, someone's liebe; what a ghastly business war is !!

It occurred to me that all my observations of German manhood from the then current movies and other sources gave one the impression that they were a somewhat super human race; six foot tall, blonde and blue-eyed. That is what the Fuhrer had aspired to no doubt but I was rather taken aback to see the first column of German prisoners passing by, some short, fat, bald, spectacled etc. etc. a straggly pathetic bunch, tired, weary but some still with that aggressive look in their eyes, some glad that at least the war and the fighting were over for them.

Several moves to different locations were made in the ensuing weeks, also being 2nd Army troops, we were at the beck and call of any Corps or AGRA needing support and CAEN had to be taken at all cost.

Being on H.Q. staff one of my 'in the field' roles was to travel with the Staff car into the forward areas and reconnoitre sites prior to the deployment of the heavy artillery. Here I would remain until the last of the units had passed through that check-point with the expectation of being picked up sometime later when the whole procedure would continue again with a type of leap-frogging action.

Following days of constant heavy shelling and later to watch a 1000 bomber raid from the outskirts of that well defended town of Caen it finally fell. Having dug ourselves in and around an orchard in the Giberville area, east of Caen, some late evening mortar fire sadly killed our Second-in-Command (Major Finch) when the shell struck an apple tree under which the officers were playing a game of cards. Here again my diary notes "heavily shelled at 22.00hrs. 2nd i/c killed, Lt. Quartermaster, Padre and Signals Officer wounded." The following day we buried the 2nd i/c and felt the terrific loss to the Regiment. Several years later through the very good services of the War Graves Commission I was able to trace and eventually visit his grave lying in peace in Bayeux cemetery.

Passing through the ruined and by now almost deserted corridor in Caen I stopped to retrieve a slightly charred but intact wall plate bearing the towns name from the still burning rubble. Somehow it had survived the crushing bombardment and would now protect it as a war souvenir. This memento I eventually carried through France, Belgium into Holland and on to the borders of Germany. Here I was lucky in a draw for U.K. leave and returned home to family bringing the wall plate for safe keeping where it continued to survive the continuing London blitz.

Sadly several years later, and happily married, my wife during a dusting session knocked it from its focal point and it broke into several pieces. I could have wept, remembering its passage through time but my good sense of humour saw the funny side of it all. Having put it together again it does have the appearance of having 'been through the wars' but still has a place of honour on my kitchen wall. Have thought over the years that I should perhaps return it to its rightful owner, but just where does one start?

Returning to the ongoing war in Europe it appeared that things were going as well as could be expected on all fronts. There were occasions when having dug a comfortable hole in the ground word would come through "we're moving again". There were no complaints as such if it was felt it brought the end of hostilities a little closer. It became a bit tough when this could happen sometimes three times in one day and with the approach of winter the earth was getting harder all the time.

It was comforting, however, to hear that the Germans were retreating down the Vire-flers road. Again my old diary reveals the path taken by the Regiment from landing in Normandy through the Altegamme on the North bank of the river Elbe, Hamburg. It gives dates and places and highlights the fact that we were forever crossing borders e.g. France into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland back into Belgium, Belgium into Holland, Holland into Germany where we remained.

Its mobility can perhaps be made clearer in an extract from the Regtl. Citation which quotes

"The unit has been deployed almost continuously in the forward areas, and the Headquarters and Batteries have frequently been under shell and mortar fire. During this time the Regiment has not only fought in an A.A. role but has been detailed to other tasks not normally the lot of an A.A. unit. These have included frequent employment in a medium artillery role, action in an anti-tank screen, and the hasty organisation of A.A. personnel into infantry sub-units to repel enemy counter-attacks. All tasks have met with conspicuous success. The unit has responded speedily, cheerfully and efficiently to every demand made on it. The unit is one where morale is very high indeed and which can confidently be given any task".

Following the distinctive role played during the N.W. Europe campaign the Regiment was awarded a Battle Honour and its Commanding Officer a D.S.O.

Depending on the impending battle plan the various Batteries would be assigned to individual tasks i.e.

275/165 Bty u/c Gds. Armd. Div. for grd. shooting.

198/165 Bty deployed in A.A. role def. conc. area.

317/165 Bty deployed in Anti-tank role.

All tasks having been successfully completed would again move as a Regiment under command Guards Armoured Division to support a new attack.

A day to be remembered was the arrival of bread after some 40 days without. I think it only amounted to one slice per man but what a relief after nibbling on hard biscuits for so long. The men to be pitied were those with dentures who automatically soaked it in their tea or cocoa (gunfire) before consuming.

Another welcome treat was the arrival of the mobile bath and clothing unit in late August '44. It was about that time that I heard a steam whistle indicating that the railroad was back in action.

When the situation allowed a truck would take a party of men to the nearest B and C Unit which consisted of a couple of large marquee tents adjoining. In one you would completely disrobe and proceed along duck-boards to the shower area. Having enjoyed this primitive delight and dried off you would then gather vest, pants, shirt and sox then queue to be sized up by the detailed attendant in charge, to be issued with hopefully something appropriate to ones stature. It didn't always work to ones liking and caused much amusement in the changing tent where swaps occasionally took place.

The unit did however serve its purpose at the time but things became more pleasant when one could retain their own gear and could sometimes get it attended to by a local admirer.

Four moves in as many days took us into Brussels where we were given a rousing reception. Our vehicles were clambered onto from all directions by the thronging crowd, showering us with hugs and kisses, flowers, and a very brief moment to sample a glass or two or wine. No time to stop, unfortunately, and soon to depart with a small recce party en route for Nijmegan. By now things were getting slightly uncomfortable having been attacked from the air during a night in the woods and the main body of the Regiment attacked in the corridor at Veghel.

Here our guns were deployed in an Anti/tank role, field role and CB role. Several troops were provided for attack to recapture the village of Apenhoff. A tiger tank was engaged by one gun and very successful CB and concentrations fired on enemy gun areas and infantry. It was thought that casualties sustained were justified as the attack resulted in the capture of 76 prisoners, one anti-tank gun and a considerable number of enemy dead, mostly to the West of the village where most of our men finished up and where a certain amount of mortar fire was brought down upon them.

The following day the main body of the Regiment arrived in Nijmegan and were deployed in an Ack-Ack role, minus one Troop still in MTB role. It was recorded at the time that on several occasions the guns had been deployed further forward than any other guns in the Second Army and in the case of the bridge over the Escaut Canal at Overpelt it was considered that the fire provided was one of the chief factors in the bridge being captured intact.

It was during a return to Belgium for a break just before Christmas 1944 that we had the good fortune to be billeted for a few days with a wonderful family consisting of Mother and Father, six daughters and two sons. The childrens' ages ranging between possibly eighteen and three. It was the time of celebrating St. Nicholas and homely pleasures had long been forgotten as regards a roof overhead, surrounding walls, and to mix with warm and friendly people. The chance to sit at a dining table on a firm and comfortable chair, food on a plate instead of a dirty old mess-tin were simple things to be appreciated beyond words and all were saddened when it was time to return into the line.

A returning Don, R would often bring little notes written in understandable English but as the lines of communication lengthened so contact diminished.

Some 40 years later, prior to a visit to The Netherlands with a party of Normandy Veterans, I decided to write to the Burgomeister of the small village of Beverst giving him full details of the family and hoping by chance that at least one member of the large family would have survived the war and perhaps was still living in the Limburg area of Belgium.

It was beyond belief that within ten days I had a letter from the very girl, Mariette, who had sent the odd letter to me and to this day still have them in my possession. We had so much to tell each other, on her side that all her sisters were married with children, and that one of her brothers who was three years old during the war was now a priest in Louvain.

As the conducted tour at the time of visiting did not go into the Limburg area of Belgium, it was arranged that a small party from the family circle would travel by minibus and that we would hopefully meet up at a suggested time in the town of Eindhoven in Holland. There was much rejoicing when the timing was spot on and a very brief meeting with an exchange of gifts took place before it was time to clamber back onto the coach.

Over the years when visiting the Continent we meet whenever possible. I have since met all surviving members of the family, visiting their homes and meeting their children. At one of the locations a field a short distance away was pointed out to me where Hitler, a Corporal at the time, had camped during the 1914-18 war.

During one conversation I asked Mariette how the family had fared during the German occupation. She told me that on one occasion a German Officer had knocked on the door requesting the family to accommodate some German troops. The Father replied that he had eight children which he was supporting and had no room for them and luckily they departed. She went on the tell me that when the Germans were pushed out of the village and the English and the Americans moved into the area her Father gladly accepted a few English soldiers to stay, suggesting the family would double up into a couple of rooms. We still find plenty to talk about over the years when corresponding and on meeting up.

In further praise of my old Regiment it is on record that before June '44 was out, a deputation of senior officers visited the unit to learn why, and how, they were usually the first guns in the line to report "READY" and higher formations were calling for their support as a unit.

The Order of March for the operation "Garden", the Northward dash to join up with the Airborne troop was headed (1) Guards Armoured Division, (2) A.A. Group (165 H.A.A. Regt.) leading. This alone should rank a citation for the 3.7in A.A. gun. Second in the Order of March on what must be one of the most daring and spectacular assaults in history.

The 3.7s when used in their field role were fired from positions amongst the infantry and that having no gun shield the layers positions were untenable. During the closing battle for Arnhem they were able to give covering fire throughout the night withdrawal. The 3.7s with their 11 miles range were amongst the very few guns available with sufficient range to cover the flanks of the 1st Airborne at Arnhem, and for a long time there was talk of the unit being permitted to carry the honoured Pegasus on their sleeve.

It was during the withdrawal of the survivors of the Battle of Arnhem, and watching the war-torn paras filing back through Hell's Highway, that I spotted and had a quick chat with a couple of my old mates that had proudly volunteered with me on that fateful day in June '41. In a flash I though "there, but for the grace of God go I". Should I have in fact survived that horrendous and tragic battle, and where are they now I wonder?

Word that hostilities had ceased came through whilst in a little German village called Tesperhude on the North bank of the Elbe, V.E. DAY, the war in Europe had ended. Time to celebrate. All Other Ranks were invited into the Officer's mess where 'issue rum' was being served up in half-pint glasses. This was a complete change to previous issues when, during inclement weather the rum ration would have to be taken in a mug of tea. Pushing all protocol aside it was time to let our hair down and enjoy. It was suggested that a bit of music and song would be in order and the question was asked as to who could play a piano accordion. I gave up the idea of not volunteering on this special occasion and said that I could, having had some professional lessons in my youth.

A search party set off down the street and a 'squeeze box' was produced and promptly placed in position. By then the rum was taking hold and I can remember getting through two verses of "Home on the range" before collapsing over backwards to a cacophony of sound as the bellows extended across my chest. Can't say the C.O. and other Officers were too pleased with the musical performance and I felt the effects of the vapours for a few days following. I made up my mind there and then that I never wished to experience the taste of Nelson's blood ever again, as I also felt about the thought of never wishing to see spam and bully beef, but time is a great healer?

Release from the service being on an 'Age and Service' basis meant that I possibly had another year or so to serve before being discharged. I would have been more than content to remain in the area of Hamburg until my release papers arrived, but unfortunately it was not to be. An urgent War Office posting, I was told, brought me back to England and a spell at Woolwich Barracks which I found most discouraging and ungratifying.

I was to join a newly formed contingent of mostly new recruits about to depart for the Far East, by mid November '45 I was on a troopship bound for Bombay. Christmas 1945 was spent in the Royal Artillery Transit Camp at Deolali where I spent a few weeks before entraining and travelling across India to Calcutta. It wasn't quite the Orient Express for comfort and cuisine, and I can remember being fired upon by rampaging dacoits at one point.

Several more weeks were spent in a transit camp in Calcutta experiencing all the delights of Chowringee and thereabouts – felt quite the pukka sahib at times before word came through that we would be sailing for Rangoon the following day.

Going aboard the S.S 'City of Canterbury' there was the usual rush for hammocks and best positions on deck. Arriving in Rangoon I was happy to receive my first letter from home in seven weeks and was a relief to be sure. I had still not reached journeys end and it was not until mid February 1946 that I joined my intended unit, a Field Regiment, on the borders of Mandalay in Burma.

I was finally homeward bound by the late summer of '46 to enjoy three months overseas leave and a return to civilian life.

Looking back over the years in the forces there were some good times and some exceedingly bad times but having come through it all reasonably fit and healthy I feel the WAR YEARS have shown me the true value of life and that, in retrospect, I feel proud not to have missed this experience of a lifetime.

Written in March 1994.

Contributed originally by gloinf (BBC WW2 People's War)

Since forming the Evacuees Reunion Association many people have asked for an

-Account of my own evacuation and why I founded the Association.

What follows is an attempt to meet that demand.

1938 and the war clouds are forming.

I was seven years old in 1938, living with my parents, three brothers and sister in a five bed roomed house in Camberwell, south London.

As the youngest of the family I lived a very sheltered life, there was always someone there to look after me. Our way of life was strictly governed by the social rules of the time and of our immediate environment.

To understand those rules you need to know the history of Camberwell from when it ceased to be a rural village in the County of Surrey and first became a very fashionable suburb of London, later .to find parts of the area degenerate into crowded slums.

The Victorian houses in our road ceased to be lived in by people who could afford to employ servants but it remained quiet and very ‘respectable’.

On Sunday mornings we children would go for walks to places such as Ruskin Park, but before we were allowed to set off we had to line up and be inspected by our father, who would look to see that our shoes were highly polished, our hair brushed and combed and that we boys’ ties were straight. “No child of mine leaves this house looking scruffy!” was his rule.

We were only allowed to go to the park and there were certain parts of Camberwell and Peckham that we were forbidden to walk through, sometimes, we broke that rule, only to be shouted at by the children who lived there. Such was the social structure of the times and the district.

During 1938 and early 1939 we saw the preparations for war being made, sandbags were stacked in front of public buildings, gas masks were issued and great silver barrage balloons wallowed in the sky over London.

The Anderson shelters were made available for people with gardens and parents were urged to register their children for evacuation. My parents attended the meetings at o schools and decided that we should go if war broke out.

As I was only eight and brother John nine, it was arranged that we would not be evacuated with our own school but with that of our sister Jean who was then nearly fourteen. Brother Ernest was to go away with his own school, but our eldest brother, Edward, had already left school and therefore stayed at home until being called up for military service.

During the summer holidays of 1939 the order came that schools in the evacuation areas were to immediately reopen and all children who had been registered for evacuation were to report daily to the school they were to go away with, taking with them the things parents had been told to pack, plus enough food for a day, but nothing else.

No one knew when, or even if, the evacuation would begin. Everyone involved had to wait for the government to issue the signal ‘Evacuate Forthwith’, which happened on Thursday 3l August 1939.

Evacuation Day

When I went to my sister’s school on the morning of Friday 1 September, with my gas mask in its cardboard box slung over one shoulder and carrying a little suitcase, I didn’t know what was about to happen. Soon we were lined up in a long ‘crocodile’ and the teachers came round tying luggage labels on us.

Then, led by the Head Teacher and two of the bigger girls carrying a banner on which were the words ‘Peckham Central Girls School’, we marched out on our way to a railway station, with a policeman in front to stop the traffic.

We didn’t know where we were going; neither did our parents or most of the teachers. All that was strictly a secret.

I can remember every detail of that day, the crowds of parents standing in silence on the other side of the road — they were not allowed to walk with us — I wondered why so many of the women were crying and why a very angry man was shouting “Look at those luggage labels, they are treating them like parcels!!!” I was wildly excited, after all my parents had told me I had nothing to worry about, it would be like going on holiday and that we would all be home again before Christmas.

Little did I know that four years would pass before I returned home for good, or that our very close family would never again be fully reunited.

I caught a glimpse of our mother in the watching crowd and waved to her, but I don’t think she could see me. I often think what it must have been like for her to return home knowing that four of her children had been taken away, to where she didn’t know, and to see four empty chairs at every mealtime and four unslept beds. How quiet the house must have been.

They marched us to Queens Road, Peckham, station. To reach the platform you had to climb a steep flight of wooden stairs and on the way up some of the girls stumbled, causing others to fall on top of them. The platform was already crowded as another school was already there.

That was when the teachers and porters started shouting “Keep back, keep back” and pushing us away from the edge of the platform. But there was no room at the back.

After a long wait a special train arrived and a mad scramble aboard began, brothers, sisters and friends trying desperately to keep together, teachers trying to push us all into the tiny compartments.

Then the porters ran along locking the doors. It was old fashioned, non-corridor train and therefore had no toilet facilities, the day was hot, the journey lasted hours and the results were inevitable.

Eventually the train stopped at a country station and the staff came to unlock the doors. Then all the shouting started again as they hurried us off the station, but first we each had to collect a carrier bag containing foodstuffs that were to be given to the people who took us in.

In each bag was also a big bar of chocolate.

Soon there were hundreds of children milling around the station forecourt, with their teachers frantically trying to keep them together.

A solution to the problem was quickly found — they put us in the pens of the adjoining cattle market, where we waited to be taken by bus to the village school.

I only saw one single deck bus that ran a shuttle service, so for so the wait was a long one. Someone found a working standpipe in the cattle market to we were all drinking from that.

Eventually we arrived at the tiny village school, but before we could go in we had to be inspected by a woman who dunked a comb in a bucket of disinfectant before yanking it through our hair.

She was the nit nurse! Inside the school the local people had set out sandwiches and drinks for us on trestle tables, but I for one didn’t take anything and I don’t think many others did.

The day had long since ceased to be a great adventure; anxiety had set in. “What was happening to us?” we wondered. I wanted my Mum! But kept quiet about it.

Then a lot of adults came in and stood in front, looking us over before pointing at a child and saying “I’ll take that one!” They were the foster parents.

One by one the children were lead away and the anxiety for those not yet chosen increased as they worried about what would happen to them if they remained un-selected.

Meanwhile Jean was keeping a tight hold on to John and me. She had been told by our parents that she and must not allow the three of us to be separated.

But they couldn’t find anyone to take all of us and John was forcibly dragged away from her and led off. Poor Jean was in floods of tears and desperately worried, feeling that she had failed our parents.

Then she and I were bundled into a car and driven to a very remote cottage, where the woman who lived there at first refused to take us in, but after being threatened with prosecution (billeting was compulsory) she opened the door.

The man who had brought us ran to his car and quickly drove away. “You can’t stay here!” she kept saying, but there was nothing we could do about it.

The cottage was very primitive and not at all like what we were used to. It lacked electricity, gas, piped water or flush toilets, the ground floors were of brick and the lavatory consisted of a bucket in a brick shed at the bottom of the overgrown garden.

There was only a single bed for Jean and I to sleep in. Jean cried all night in spite of me force feeding her some of my chocolate bar in an attempt to make her feel better.

One of the first things we had to do when placed in a billet was to send a postcard home showing our new address. We had been given the postcards back in London and told how important they were, because until they received them our parents did not know where we were.

We younger ones were told what to write on the cards, such as “Dear Mum and Dad, I am very happy here and living with nice people, don’t worry about me.” However it seems that I wrote on mine, “We’ve lost John and the stinging nettles got me on the way to the lavatory!”

“I’ve always wanted to live in a sweet shop! “®

-

After a couple of weeks the Billeting Officer arrived at the cottage and told us to collect our things as we were being moved into the main village (Pulborough, West Sussex). We found ourselves back near to the railway station.

Jean was billeted with the family of a signalman and, to my great delight; I was taken to live with people who ran a shop that sold sweets and many other things. They lived on the premises.

Apparently I said “I’ve always wanted to live in a sweet shop!” and was told that if I was a good boy and did all the jobs they gave me I could have one pennyworth of sweets every day and two pennyworth on Sundays, but I must never help myself.

The jobs included carrying in the buckets of coal, chopping firewood, feeding the chickens, helping on the allotment and, because they had a tea room, doing mountains of washing up.

Very soon they had a surprise because John was also brought to live there, although they had never been asked. He had been living at an outlying farm and was not very pleased about leaving it.

Jean’s billet with the signalman’s family did not work out and she was again moved. That meant John and I saw very little of her because her new foster parents would not allow us to visit. I don’t know why.

Then I was told that John was being moved to another billet because our foster parents could not manage to look after the two of us. He was not far away and I saw him nearly every day, but it did mean that for the first time in my life I was on my own, with no older brother or my sister to look after me.

Another problem for us boys was that because we had been evacuated with our sisters’ school we did not know any of the teachers or pupils other than Jean. When the Village Hall began to be used for the evacuated girls school John and I had to be taught at the Village School.

Initially, as could be expected, there was friction between the village boys and we evacuees, they shouted at us “Dirty Londoners”, we called then country bumpkins and fights often broke out.

Poor John suffered from bullying much more than me, but I was very upset when I saw chalked up messages saying “Vaccies go home. We don’t want you here!” Of course that had been done by a few silly children and was soon stopped, but we evacuees were all suffering from homesickness and all we wanted to do was to go home, but we couldn’t.

Soon after that we were all chalking up big Vs, that being Churchill’s sign for V for Victory. I was given a V for Victory badge that I wore for years. After a year or so John was moved to the Village Hall School, so I saw even less of him.

As the war dragged on.

Earlier I said that we had been told we would be home for Christmas. Many evacuees’ parents defied the government and did allow their evacuated children to return home for Christmas in 1939.

The result was, as the government had feared; many evacuees never returned to the reception areas. My parents were made of sterner stuff and we were not allowed to go home, which was a great disappointment.

In fact our first Christmas back at home was not until 1942, after which we had to return to Pulborough.

What is not generally known is that when an evacuee reached school leaving age they were no longer classed as being evacuees by the government. The allowance paid to foster parents ceased and it was entirely up their parents what happened next.

Of course most evacuees went home, but some obtained work in the reception areas and stayed with their foster parents. For many children the school leaving age was fourteen, but as Jean went to a Central school she left a year later and went back to London.

During the Battle of Britain the skies over Pulborough were the scene of many dogfights and we saw planes explode and come crashing down.

The German fighter planes would zoom low over the village machine-gunning as they went. Anything was their target, even school children, but fortunately none of us were hit.

Then the blitz began and at night we could see the red glow in the sky of London burning.

Very often a policeman would come into school and an evacuee was taken out, we fully realised that that child was probably being told.

Disaster struck the nearby market town of Petworth, where the boys’ school received a direct hit, killing all the children and their teachers.

The threat of invasion turned Pulborough into a fortified village, surrounded by barbed wire, its roads fitted with tank traps. Huge concrete gun emplacements were built, also machine gun posts and slit trenches made behind roadside walls and in many buildings.

Thousands of Canadian soldiers were camped all around the area. Many would call at the sweet shop tearoom, making more washing up for me!

Homesickness-the ever-present problem.

I believe that all evacuees suffered from homesickness, whether they were being well looked after or not. I know I did. It was always there, no matter how hard you tried to keep it away. But in those day’s homesickness was not acknowledged in the way it is now and evacuees showing signs of it were soon told to stop moping around and asked “Don’t you know there’s a war on?” Evacuees became very adept at hiding their inner feelings. You would put on a smiling face and never let anyone see you cry.

That led to many foster parents believing their evacuees were happy, not realising that they were crying themselves to sleep nearly every night.

I managed to hide my homesickness so well that no one knew about it. Apart that is for one occasion that I will never forget. There was to be a concert in the village ball and my foster parents were given a complementary ticket in return for displaying a poster in the shop.

They didn’t want to go so I was given the ticket. Wearing my best suit and tie I felt so important as I was shown to my seat on the night of the concert. It was the first time I had ever been to such an event, especially on my own.

All went well until very near the end when all the caste came on stage, the lights turned to a red glow and they started with some of the songs that my parents used to sing, such as ‘Red sails in the sunset’, ‘The wheel of the wagon is broken’. Then came ‘Be it ever so humble, there’s no place like home’. That was too much for me.

I started crying and, try as I might, could not stop. At first no one could see me because the lights were all so low, but then every light in the hail was switched on and the audience stood to sing the National Anthem, the show was over, but I couldn’t stop crying, so I made to get out of the hall as quickly as I could, out into the anonymity of the blackout.

People were looking at me and one woman tried to put her arm round me, but I pushed her away. By the time I had walked back to my billet I had composed myself and showed no signs of any problem, but then I worried for days that someone would come into the shop and say, “Your evacuee was very rude to my wife the other evening”.

But no one did.

Contributed originally by Robert V Bullen (BBC WW2 People's War)

I was born in Brixton, London SW2 and lived in Endymion Road, Brixton Hill from before and during the war.

My wartime recollections commence in Sept 1938 at the time of the Munich crisis. I remember feeling slightly disappointed as a 12 year old that there wasn’t going to be a war, having heard stories from my uncles of WW1, which didn’t feature the horrors and sounded exciting. We had been to a local school to collect our gas masks and afterwards went to the pictures to see “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs” the first full length Walt Disney cartoon film.

1939 started with a personal event as I had an appendicitis operation in March. The hospital situation was different then. My father had joined the hospital savings association through a group run by an employee of his company and this paid for my operation and stay in St. Thomas’s hospital at Westminster, where the financial side was run by the Lady Almoner (treasurer). My stay lasted five weeks as I had been near to peritonitis. I was in the men’s ward and in a bed next to a blind veteran of WW1 from the St Dunstan’s Home. He had a kidney problem. One treat was that your family could provide you with new laid eggs for your tea, these would have your bed number marked on your shell and boiled. I recently discovered the letters that I had written to my mother and one mentioned that the air raid sirens had been tried out in the area, a sign of the preparation in case of war. The letters were written in pencil for the ball point pen or biro as it was originally known had not been invented.

In May we had a holiday in Littlehampton. This was the first holiday that we had had and it was partly convalescence for me. Photographs show that beneath my clothes I was still bandaged after the operation, a sign of how long healing took then. The war preparations could be seen as we used to watch the Territorial Army drilling on the green just above the beach. There was a Pierrot show on the green and I went in for a children’s talent show playing the piano and won a box of liquorice allsorts. Later I received a card inviting me to the final competition of Sunday 3rd September. We couldn’t go and maybe it was cancelled as it was the day that war broke out. Perhaps a career in music was blighted by the war!

In August I changed schools to Clark’s College, to prepare for Civil Service examinations. Two weeks after starting, the War commenced. I could have been evacuated with the school, but my parents wanted the family to stay together and so I took a postal tuition that was offered, this was not satisfactory and was discontinued after a couple of months, ending my formal schooling at about age thirteen and a half. We lived in my grandmother's house and I then helped to serve in the little tobacconist's kiosk that she had opened at the back of the house.

During that summer the council had erected an Anderson air raid shelter in our back garden. On Sunday morning of 3rd September at 11.00 we listed to Neville Chamberlain’s broadcast saying that we had declared war on Germany, during this broadcast the air raid sirens sounded and we all went down the shelter. It was the only time that we used it as it would have been too small for us all to sleep in, so when the Blitz started in September 1940 my parents, sister and I all slept in the cellar of the house and my grandmother and aunt stayed in their bedroom on the ground floor.

The period from September 1939 to May 1940 became known as the “Phoney War”. It was anticipated that it would be like World War 1 with armies in lines facing each other and newspapers published wall maps of the front together with paper flags of the nations involved to mark the opposing positions. I had one of these maps on the bedroom wall. The Blitzkrieg of May 1940 ended that idea with the German army invading Holland and Belgium and surrounding our troops at Dunkirk. I remember seeing a train passing through Brixton station loaded with troops who had been rescued from Dunkirk, leaning out of the windows and waving.

An invasion of Britain was expected after Dunkirk and the Local Defence Volunteers ( LDV ) which later became the Home Guard was formed and I remember seeing an uncle of mine, a World War 1 veteran drilling with them in the local park. There was a fear at this time of spies among the foreign refugees who had fled from the Nazis before the war so they were rounded up and sent to the Isle of Man. My grandmother who let rooms in her house had an Austrian refugee staying with her. He was taken away by the police and first sent to the Isle of Man and eventually to Canada.

The Battle of Britain was in August and September 1940 and was followed by the Blitz. The war was well reported in the press but I remember some of the claims of German aircraft shot down in the Battle of Britain, 184 on one day, being much reduced later. This was probably a mixture of propaganda and double claims.

Our first experience of bombing was on October 10th when an oil bomb fell in the front garden of the house next-door-but-one and the burning oil ran along the gutter past our house and we could see the flames through the cellar grill. As a 13 year old I did not experience any fear and took pleasure with my friends in collecting shrapnel that had fallen in the streets on the night before. Sadly the next night after our oil bomb an uncle of mine was killed by a bomb near to his house in Epsom. He had moved there with his family as his son had been apprenticed the year before to a racing stables and my uncle thought that the family would be safer out of London. That night he had left the shelter and gone to meet his daughter coming home from work and was killed by a direct hit.

Our second experience was on 19th March 1941 when we were hit by 2 incendiary bombs. The first was by our chicken house, kept to supplement wartime rations, and was put out by my father and me. We came in from the garden and were going to have a congratulatory cup of tea when burning was smelt. We went upstairs and found that a second incendiary had fallen through the roof into our living room and through the floor there to my grandmother’s room on the ground floor. Fortunately she was with us in the cellar. The fire brigade was called and came to put out the fire, air raid wardens were also present and an amusing mistake occurred as senior wardens wore white tin hats and we thought that we had one there but it turned out to be a neighbour who had put an enamel vegetable colander on his head. He was known from then on as Colonel Colander.

The continuous Blitz ended in August 1941. I started work as a junior clerk with Lambeth Borough Council. Instead of being employed at the nearby town hall I was given a job at the Council's cemetery office, a tram or cycle ride away at Tooting. Fortunately the mass burials of the Blitz had finished and the task was not too hard. I felt as if I was working in a park. At this time I started at evening classes to make up for my lost schooling and to prepare for matriculation. I had also earlier studied shorthand and typing.

After the Blitz life seemed to settle. Everyone went about their work and their leisure, going to the pictures ( cinema ) and to shows. We had rationing but accepted that and I certainly never felt deprived. The war was well reported on the radio and in the papers. Virtually everybody had a relation or friend in the armed forces and sadly there were some who were killed in action.

Earlier in the war many coal miners were called up leaving a shortage, so that when in 1943 the call up age was reduced to 18 some of those conscripted were drafted down the mines. These were known as Bevin boys after the minister of Labour Ernest Bevin. As I thought this change would prevent me sitting the matriculation exam ( although I recently discovered that I could have applied for a delay in call up ), and as I did not wish to go down the coal mines I volunteered in February 1944 to join the Navy. I had always been interested in the sea and I followed in the footsteps of a friend who had joined a few months earlier. I could have entered the Navy when I volunteered or wait until I was 18, which I chose to do and was called up the day after my 18th birthday on 3rd May 1944. I joined at HMS Royal Arthur an ex Butlins holiday camp in Skegness.

I was then sent for training to HMS Ganges at Shotley, near Ipswich and was there when the D-Day landings occurred. I remember lads from my course being drafted from the Navy in to the Army where they we needed more. I was probably all right as I was a volunteer.

On 23rd June the family house was hit again, this time by one of the first V1 flying bombs ( see photo at top ). It fell in the next road and blew the back of our house off. Fortunately none of the family were injured, but warden’s records show that 8 people were killed, 14 seriously injured, 42 houses demolished and 48 badly damaged by the bomb. I was granted compassionate leave to be with my family. There were emergency services there including a mobile laundry, supplied by the makers of Rinso. As this was the site of one of earliest V1 bombs it was visited by the Lord Mayor of London, Sir Frank Newsom-Smith and the Mayor of Lambeth, Alderman Lockyer - see the next story for a photo of the visit. While home I went into Brixton and was there when another V1 bomb fell near to Lambeth Town Hall. In the incident 23 were killed and 41 seriously injured. I was in Woolworth’s store and the blast came through the doors and a soldier standing next to me was cut by flying glass. I returned from leave and on 21st July my grandmother died of pneumonia, I suspect brought on by the shock of the bomb. She was 82.

On return to the Navy I had to change my course to make up for the time lost in training. After completing basic training I went to H.M.S. Valkyrie on the Isle of Man for Radar training. The Navy here had taken over hotels on the sea front at Douglas. More training followed at HMS Collingwood at Fareham in Hampshire, where I was able to visit at second cousin and his family at Warsash, where he was an officer in charge of servicing landing craft. This completed my training and in November 1944 I went to Chatham Barracks to await drafting to a ship.

I joined my first ship, HMS Locust in Harwich on 18th November. She was a gunboat designed for service on the China rivers and had taken part in the Dunkirk evacuation, the Dieppe raid and the D-Day landings. She remained at Harwich and I was able to get home for Christmas leave and for a day or week-end visits. The war in Europe ended on 8th May and on the 14th we went over to Holland with the Captain in charge of minesweeping. We were first at the Hook of Holland and then moved to Ijmuiden. From the Hook of Holland we were granted shore leave and the Army provided trucks to take us in to Rotterdam. We saw armed resistance workers arresting collaborators and in a struggle we saw a wig knocked off the head of a woman whose head had been shaved as she had been with the Germans. The locals wanted cigarettes, perhaps as currency and I bought a camera and film for some from a young lad.

At Ijmuiden there were German troops lining the road waiting for a ship to take them back to Germany. We were able to go freely into their deserted defence pill boxes where there were rifles and ammunition so we did some target practice at signs on the beach. We took part in a liberation parade, marching to a Canadian army band. The Canadians had liberated the town and I have since in 1995 and 2000 taken part in anniversary celebrations with them where the Dutch have been grateful and generous hosts to us.